ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Titia Hulst

The emergence of American Pop art as a major avant-garde movement had a significant impact on the market for contemporary art and, with it, the perception of America’s newly achieved cultural superiority. A detailed examination of sales records of avant-garde galleries in New York reveals Pop’s appeal to collectors (especially businessmen), despite significant critical disdain, and links the formal qualities and subjects of Pop art to widely-held assumptions about modes of viewing and social class.

“Can 50 Million Frenchmen Be Wrong?” This provocative question headlined a 1990 New York Times article on French cinematic taste, in which the author puzzled why Mickey Rourke, a decidedly minor actor in the United States, was considered a major talent in France. Rourke was described as being “mobbed at film festivals and movie openings, lionized by cafe society, ardently defended by intellectuals and critics,” including Les Cahiers du Cinéma, which was, the author noted, “the famous magazine of film criticism that launched La Nouvelle Vague, Godard and Jerry Lewis, and is so highbrow it refused to interview the French director Claude Lelouch ... for 24 years.”1

Tongue firmly in cheek, the writer underlines the irony of what could only be understood as a complete role reversal. The French, after all, had been the international arbiters of taste in all matters of culture since, at a minimum, the nineteenth century. This role was taken over – or stolen2 – by, of all people, the Americans, who until the 1960s had been considered the crass antithesis of the erudite connoisseurs in Europe’s high society. These stereotypes may explain why some scholars attributed the French outcry that followed Robert Rauschenberg’s win of the International Prize at the Venice Biennale in 1964 to the fact that he was an American.3 This view was encouraged by Alan Solomon, the curator of the American Pavilion, who boasted in his report to the U.S. government that “the American exhibition had the effect of making dramatically apparent the end (temporarily at least) of a hundred and fifty years of French dominance of art.”4 Yet the French outrage was not, or not merely, based on nationality (American abstract painter Mark Tobey had won the same prize just six years earlier without much fanfare) but spoke instead to the style in which Rauschenberg worked: he was considered an American Pop artist (see Figure 1). The French art world was inflamed because the prize confirmed the growing international taste for Pop and its utterly banal subject matter that threatened the legacy of French avant-garde painting.

In this article, I use the insights of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s analysis of taste in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (1979) and primary art market data to suggest new directions for art historical research on postwar American styles and gender preferences.

Fig. 1: Editorial Cartoon, France Observateur, 25 June 1964

The emergence of the United States as the West’s leading tastemaker was fueled by the postwar economic boom, in line with historian Fernand Braudel’s observation that accumulated wealth is a prerequisite for the development of markets in general.5 American prosperity created a class of newly wealthy businessmen, who, seeking cultural capital, became avid collectors of art, kicking the market into high gear with large infusions of cash. With sustained growth, the centre of the international market for contemporary art, a locus of cultural power, migrated from Paris to New York over the course of the 1960s and 1970s, significantly impacting the fortunes of the French market, and, as many French cultural critics believed, the livelihood of French artists.6 A Whitney Museum publication documenting the impact of American art on Europe in the early 1960s confirmed that “any American institution mounting a retrospective of almost any major American artist of these years has to borrow key works back from Europe. This is a reversal of the earlier trend in which American collectors snapped up vast numbers of the master works of European modernism.”7 By 1980 New York had been firmly established as the dominant center8 of the Western European economy (to borrow a phrase from Braudel), definitively positioning the Americans as the new international cultural elite. The United States had finally achieved what Bourdieu called cultural nobility, “the stake in a struggle that has gone on unceasingly, from the seventeenth century to the present day, between groups differing in their ideas of culture and of the legitimate relation to culture and to works of art.”9

In its Braudelian longue durée, the history of capitalism saw geographical shifts of dominant Western economic centers (from the Italian city-states of the quattrocento, to Antwerp in the sixteenth century, to Amsterdam in the seventeenth century, to London in the early nineteenth century) where increased wealth and social mobility produced multiple generations of powerful aristocratic and merchant families. The slow pace of these shifts enabled a curious sort of amnesia, a collective forgetting, whether deliberate or unconscious, of important aspects of a group’s cultural history. The newly wealthy turned to the collecting of art, as a signifier of good taste, to gain access to the upper strata of society. But subsequent generations of these once newly wealthy European families were quick to forget that the works adorning their family’s castles and mansions had originally been purchased as a social currency that mainly reflected prevailing taste and fashion. Instead, the families’ art collections were absorbed into a narrative of connoisseurship and taste that attributed the owners’ cultural sophistication to their lofty position in the social hierarchy.10

Yet as Bourdieu painstakingly demonstrated, taste in art, literature, and music correlates more closely with one’s educational level and only secondarily to one’s social origin. Taste in the fine arts, he observed, comes down to training the eye: “the capacity to see (voir) is a function of knowledge (savoir).” 11 Familiarity with the art collections passed down through the generations trained owners in the art of seeing, which, over time, instilled the ability to discern the quality of works of art in purely formal terms – the circumstances of the original acquisition all but forgotten. However, as Bourdieu reminds us, the hierarchy of tastes in the arts (the preferences for medium, subject matter, and styles) has always mirrored, not emanated from, the social hierarchy of consumers.

Art collecting in the United States has at times been caught up in contradictory beliefs, the notion that taste is a by-product of social class, on the one hand, and on the other, faith in the potential for social mobility assured by the American dream. In the late twentieth century, for example, the U.S. press was fascinated by Herbert and Dorothy Vogel, a New York couple whose large art collection was remarkable not just for its size, but also for the apparent incongruity between the couple’s modest socioeconomic profile (Herbert was a postal worker and Dorothy a librarian) and the nature of the art works in their collection. The Vogels’ appreciation for highbrow conceptual and minimalist art was widely perceived to be at odds with their social station. “If it’s possible to be proletarian art collectors, the Vogels may have invented the category,” gushed a reporter for Blouin Art Info, an aspirational online journal for art collectors.12 Similarly, the Washington Post marveled that the Vogels had assembled their collection using their “intuition and personal taste, trusting their instincts rather than the advice of high-priced consultants or galleries.”13 The news accounts highlighted the couple’s social status but omitted any mention of their education. Yet in the 1950s Herbert Vogel had attended art history lectures at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, at the time considered on a par with any Ivy League art history program.14 Dorothy Vogel held a master’s degree in library science (an interdisciplinary field built around book collections) and had worked full time for the venerable New York Public Library.

Despite the sensationalistic reporting on the Vogels’ highbrow purchasing habits, the implied correlation between taste and social standing was old news in the United States, the European tradition having crossed the Atlantic. The wealthy U.S. collectors that emerged in the latter part of the nineteenth century especially coveted art that had been associated with Europe’s upper classes. Industrialists and financiers such as Henry Frick and Andrew Mellon were secure in their wealth but not in their social status – and dealers such as Joe Duveen and Paul Durand-Ruel had been quick to take advantage. Duveen matched the American insatiable desire for status with the British aristocracy’s perennial need for cash, while Durand-Ruel convinced Americans of the merits of the new French Impressionist painters by exhibiting their work alongside his personal collection of European master paintings in New York in 1886.

Meanwhile, taste hierarchies, based on specific criteria (formal qualities, subject matter, style, medium) and correlated to specific consumers, began to inform cultural assumptions in the United States. As Michael Leja noted, the American press in the late nineteenth century tended to equate the taste for legible, illusionistic, and sentimental paintings with socially inferior viewers – rural, poor, very old or young, and female. By contrast, socially superior viewers – described in these reports as upper class, urban, mature, male – were credited with “distanced and reserved styles of interaction and a preference for art works that subordinated illusionism and narrative to “higher truths” and formal brilliance,”15 qualities that were closely associated with modern French painting. Andreas Huyssen similarly found that “political, psychological, and aesthetic discourse around the turn of the century consistently and obsessively genders mass culture and the masses as feminine, while high culture, whether traditional or modern, clearly remains the privileged realm of the male activities.”16

The presumption that male viewers preferred less accessible and more formal modes of painting appeared to be derived from the art historical discourse that had developed since the advent of modernism. Unable to fit modern painting within the natural cycle of styles that had informed scholarship since the Renaissance, critics and art historians instead started to focus on form as the essential quality in works of art17 and linked artists to the great masters of the past by invoking the Romantic discourse that posited artistic genius as a talent that naturally occurs, but exclusively in male artists.18 Emile Zola, for example, in describing “the birth of a true artist” Edouard Manet, emphasized that the painter had eschewed formal training to be able to paint “Nature as it really is, without looking at the works or studying the opinions of others,” while situating Manet’s work within “the great family of works already created by mankind.”19 In 1910 Maurice Denis argued that Cézanne, “the Master of Aix-en-Provence,” was “at once the climax of the classic tradition and the result of the great crisis of liberty and illumination which had rejuvenated modern art.” Denis observed “something of El Greco in him and often the healthfulness of Veronese” but insisted that the artist “such as he is he is so naturally, and all the scruples of his will, all the assiduity of his effort have only aided and exalted his natural gifts.”20

Taste refers to personal and cultural patterns of choice and preference and implies drawing distinctions between such things as goods, manners, styles, and works of art. Refinement and good taste – the ability to discern quality – have often been construed as innate attributes of the highest social classes. Bourdieu decisively upends such assumptions, showing that cultural taste is acquired through education, which endows individuals with the ability to perceive what is culturally “noble” (in “good taste”). Past purchases of works of art, which were perhaps less motivated by the perception of enduring quality than by their popular or fashionable appeal, informed the sensibilities of generations and thus informed taste.

Formal and stylistic properties in art – criteria in taste – have often been viewed in terms of masculine/feminine paradigms within the art historical discourse. With this in mind, I looked closely at gender differences in consumer taste during the period of Pop’s ascendancy over abstract expressionism in the American art market. Pop art’s disruptive effect is routinely ascribed to its use of mass-culture or kitsch imagery – a wink at the commercial stakes that are disavowed in the traditional discourse of “disinterested” art. Pop’s status within the taste hierarchy was therefore initially dubious at best, but the new art, widely dismissed as distastefully middlebrow, held enormous appeal for an emerging class of art consumers, the newly wealthy businessmen who entered the market in the postwar period. While other significant market shifts, including changes in the functions and motivations of various participants also occurred during this period, I will limit myself here to highlighting apparent gender differences in the primary art market to show how such an approach allows us to further nuance the existing discourse surrounding Pop Art.

Data from sales in the primary market can yield potentially important insights by allowing us to correlate consumer tastes with formal attributes in art. The original sale of a work may be the only point at which we can hope to glean any information about aesthetic preferences per se, since, absent an established secondary market or auction value, the future monetary worth of a work of art cannot reliably be predicted. To be sure, art purchases are often mediated through dealers, but common sense suggests that buyers may seek out particular dealers at least in part on the basis of shared aesthetic affinities. Sales data cannot capture a number of details of consumer preferences in the primary art market: the reason for the purchase (to build a collection versus to match the color scheme of the living room), demographic information relating to class, educational level, and so forth. Despite such limitations, transaction data can yield insights into consumer tastes that can fruitfully be enlisted as part of art historical study.

Research into the decision-making processes underpinning the purchase of art has generally lagged, in part due to a paucity of information, especially in the secretive primary market. By contrast, transaction data in the secondary or auction markets are widely available, which may be why most art market scholarship has focused on auction purchases of works already absorbed into the art historical canon, with the motivations for their original acquisition long forgotten.

Fortunately, a trove of sales-related information was preserved in the archives of several avant-garde art galleries that operated in the primary market in New York during the 1950s and 1960s – material that makes it possible to compose a more nuanced portrait of the American collectors that embraced Pop. Complete invoice books are available in the archives of the Betty Parsons, Downtown, and the Martha Jackson galleries, as are a list of sales from the Hansa Gallery and inventory cards from the Green Gallery in the Richard Bellamy archive. The exhibition archive of the Stable Gallery included price lists and the names of the collectors of works by artists Robert Indiana and Andy Warhol. The Leo Castelli correspondence archive yielded another 1,900 transactions.

After transcribing the data in these sales archives, I was able to create a database containing 19,620 sales transactions that took place between 1946 and 1969.21 Each record of a transaction includes the gallery name, year of sale, the middleman (if used), the purchaser’s name, gender, and location, and the type of purchaser (i.e., private individual, business, museum, etc.). Each record also contains the name of the artist, title and date of the work, style, medium, price, and the discount that was applied for each transaction. The following portrait of American collectors emerged from my data.22

In the period 1951–1959, more individual purchasers were active in the primary market than at any other time in the sample, accounting for 68 percent of all transactions. The data suggest that the incidental purchaser of art was the bread-and-butter for galleries at this time. Most of these individuals made relatively few purchases (one or two works), which suggests they purchased art works for decorative purposes. The number of individual purchasers peaked in the period 1951–1954, which, not surprisingly, corresponds to the boom in housing construction in the same period.

Within the individual purchaser category, I identified gender and marital status (as reflected on the invoices) in order to test whether gender played a role in selecting works for purchase. It bears keeping in mind that women, especially in the 1940s and 1950s, are likely to have been undercounted in my sample due to the prevailing etiquette to address invoices to the male head of household regardless of who instigated the purchase. Even so, female purchasers turned out to be significantly more active in the art market between 1946 and 1955, which comports with the widely held notion that the purchase of art in the United States during this time was part of the domestic or female realm. Men increased their participation in the market in the late 1950s and, the data show, purchased more works in the period 1961–1964 than at any other time between 1946 and 1969.

The data revealed some striking correlations between purchasers’ gender and their affinities for particular styles. Women showed a clear preference for abstract art, especially expressive abstraction, while men preferred representational art in the form of landscapes and figuration. Women purchased relatively more works by Jackson Pollock, Richard Pousette-Dart, and Mark Rothko, than men, for example. While the early female preference for avant-garde abstract painting may seem surprising to some, it is useful to remember that the French avant-garde in the 1910s and 1920s had found an attentive audience in female dealers and collectors such as Berthe Weill, Gertrude Stein, the Cone sisters, the female founders of the Museum of Modern Art, Katherine Dreier, and so on. The same held true for the postwar American avant-garde painters. Jackson Pollock, for one, owed his initial success first to Peggy Guggenheim, who, after she decided to return to Italy, was unsuccessful in her efforts to place the artist with established New York dealers. In the end, it was another female dealer, Betty Parsons, who was willing to take him and his colleagues on. Moreover, the first museum to give Pollock a solo exhibition in 1945 and purchase his work for its permanent collection, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, did so under the inspired leadership of its female director, Grace McCann Morley.

The female preference for abstract art that is revealed by the data calls into question the discourse that emphasized the masculinity of the abstract expressionist painters, their works, and their audience. Modern and contemporary art historians tend to give more weight to the critical response to new art than to the reception of art works in the primary market, which is why, under the influence of the rhetoric of critics such as Harold Rosenberg, abstract expressionist works came to be seen as essentially male. One art historian, Michael Leja, may have had this in mind when he asserted that works such as Pollock’s were emblems of masculinity that distinguished the abstract painters’ works from “Kitsch or the feminine.”23 The rhetoric of masculinity continued even after Jackson Pollock’s canvases were reproduced in the pages of Vogue, an emblem of femininity, used as a backdrop for a fashion shoot by renowned photographer Cecil Beaton. T.J. Clark argued that the “photos were meant to produce a slight intake of breath” by the juxtaposition of the feminine and the masculine and lamented that it is the fate of complex art “to be used, recruited, and misread.”24 For Clark, the Vogue photographs “raise the question ... what possible uses Pollock’s work could anticipate, what viewers or readers expected, what spaces it was meant to inhabit; and, above all, the question of how such a structure of expectation can be seen, by us in retrospect, to enter and inform the work itself, determining its idiom.”25

Both my data and the Vogue photographs suggest that art historical pursuits that aim to answer Clark’s questions should focus on the possibly gendered reception of Pollock’s work and study the purchasing and display of abstract expressionist works by female collectors. That Pollock’s work contains a strong decorative element was revealed by artist Louise Lawler in her 1984 photograph Pollock and Tureen, Arranged by Mr. and Mrs. Burton Tremaine, Connecticut, which shows the visual affinity between Pollock’s drips and the curves of what appears to be a piece of nineteenth-century Meissen porcelain, as displayed by Emily Hall (Mrs. Burton) Tremaine, the far more active half of the collecting couple.26

The above examples make clear that, despite the strong female support for abstract expressionism from its inception, critical interpretation has governed art historical discourse without once considering that the heroic and masculine paintings may not have found an equally masculine audience. The nineteenth-century assumption that female viewers were not sophisticated enough to understand and appreciate avant-garde art, still held.

While the 1950s are routinely considered to have been the heyday of expressive abstract painting in the United States, this is not reflected in the purchase data. In terms of sales, expressive abstraction ranked equally with the land-, sea-, and cityscapes, and other figurative works during the 1950s. The preference for figuration (humans and animals), especially among private collectors, continued to be strong throughout the 1960s. However, other figurative works (featuring any type of scape or objects) lost ground during the 1960s to what I have labeled cool abstraction – works that feature strong linearity without a readily discernable subject matter. This shift can in part be explained by the increasing prevalence of business and institutional buyers. After all, cool abstraction is the central feature of the Minimalist works that have traditionally been favored by corporations, either for its perceived neutral attitude to the world, or, as Anna Chave would argue, for the “rhetoric of power” embedded in its structures.27

Prints led the boom in sales between 1958 and 1959. The most popular prints were by the social-realist artist Ben Shahn, who was represented by the Downtown Gallery. Shahn, the second best-selling artist in the data sample, had been a prolific print maker producing more than 40 different prints which sold over 1,800 copies. The prints, which feature a strong linear style, were popular both inside and outside the art world. In 1959 Henry Geldzahler, who was soon to become an influential curator, purchased Shahn’s popular Sacco and Vanzetti print. Around the same time Andy Warhol chose Shahn’s equally popular Calabanes print, a linear black and white rendering of an abstract jumble of TV antennas. Of the 887 private purchasers of the Shahn prints whose gender could be identified, 70 percent were male.

What is striking about the difference in taste between genders as highlighted above is that it is very reminiscent of the Renaissance theories on style and gender. High Renaissance artists, especially those working in Rome, believed that disegno, the linear rendering and compositional design born from intellect, was masculine, and colorito, a composition created with color, was feminine.28

The notion of European, especially French, cultural superiority, along with the preconceived ideas about social status and modes of viewing so much suffused Americans’ conception of art that when Pop art burst onto the scene in the 1960s, it was met with bewilderment and hostility. Pop’s legibility, familiar iconography, and often clichéd subjects could not possibly rank as serious art. Critical response to Pop art was devastating. Art historian and critic Max Kozloff impugned Pop collectors as embracing the “pin-headed and contemptible style of gum chewers, bobby soxers, and worse, delinquents.”29 Peter Selz, a respected curator at the Museum of Modern Art, strongly opposed the Pop works, explaining that

“The reason these works leave us thoroughly dissatisfied lies not in their means but in their end: most of them have nothing at all to say. ... The interpretation or transformation of reality as achieved by the Pop Artist, insofar it exists at all, is limp and unconvincing. It is this want of imagination, this passive acceptance of things as they are that makes these pictures so unsatisfactory at second or third look. They are hardly worth the kind of contemplation a real work of art demands.”30

But Roy Lichtenstein, in an early interview about his art, rejected this reading of Pop out of hand. He contended that art since Cézanne had become “extremely romantic and unrealistic” and defended Pop’s style as engaging with America’s industry and commerce. Pop, he said, is an “involvement with ... the most brazen and threatening characteristics of our culture, things we hate, but which are also powerful in their impingement on us.”31 Lichtenstein’s observation helps explain why a new generation of male collectors were keen to purchase Pop. These – mostly business – men may have simply derived great pleasure from seeing their commercial occupations reflected in the Pop works, manifesting what Michael Baxandall called the “period eye.”32 The German collector Peter Ludwig explained this best when he said “Pop art equals Cubism in importance because for the first time in our century, it represents and acknowledges industrial society as an important reality. My admiration for Pop art stems from the fact that it does stand up to the realities of this life and does not retreat from them.”33 However, the art establishment at the time was firm in its conviction that this preference for legible and narrative art could only be associated with a lower-class mode of viewing, and rejected Pop with outrage. When a highly-regarded dealer in modern art, Sidney Janis, mounted one of the first exhibitions of Pop Art, titled “The New Realists,” in 1962, the abstract expressionist painters Mark Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, Philip Guston, and Robert Motherwell all resigned from the gallery, aghast at Janis’s embrace of these ostensibly lowbrow works.

Collectors of the new Pop Art, scorned for their lack of taste, were attacked in the same terms that had dogged American collectors since the founding of the Republic. In 1827, a Mrs. Frances Trollope traveled to the United States and, after meeting some American collectors, reported scathingly of “the utter ignorance respecting pictures to be found among persons of first standing in society” and that the Americans’ wish to patronize the arts was “joined to a profundity of ignorance on the subject.”34 The Americans who traveled to Paris in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to acquire cultural refinement were treated with similar disdain. They reportedly failed to recognize greatness in works of art, and, worse, at times showed a preference for reproductions over the original works.35 The image of cultural ignoramus continued to dominate the perception of American collectors after World War II. In 1949 Russell Lynes observed that when “Americans are characterized by foreigners and highbrows, the middlebrows are likely to emerge as the dominant group in our society.”36 This insecurity may have led Life magazine, whose pages regularly featured highbrow art, to mock both Pop artists and their collectors. A 1964 article on Roy Lichtenstein was headlined, “Is He the Worst Artist in the U.S.?” A year later Life’s editors poked fun at Pop’s collectors in a photospread titled “You Bought It Now Live with It.”

This brief analysis of the sales data illuminates some of the forces that propelled Pop art’s cultural influence. My sample captures the moment of a shift in taste – the eclipse of expressionist abstraction by Pop Art – that correlates with a masculinization of the American art market in the period 1961-1964. Moreover, the data deepen our understanding of the businessmen collector’s embrace of Pop.

In the first half of the twentieth century American women seemed far more interested in the avant-garde than American men. Meyer Schapiro suggested in a lecture in 1950 that female interest in the new art could be linked to the women’s “historical moment of general stirring of ideas of emancipation,” which had made women more receptive to the “manifestations of freedom within the arts.”37 The early involvement of the wealthy women in avant-garde art potentially explains the failure of a strong American primary market to emerge in the first part of the twentieth century. While actively supporting avant-garde artists with purchases and even with living/working arrangements in the form of stipends or studio space, the women either held on to or donated their acquisitions to museums, and thus ironically impeded the establishment of a robust marketplace for art in the United States. The first director of the Museum of Modern Art, Alfred Barr, suggested as much in 1936 when he observed that collectors from wealthy families actually had not done much for the art market: “One of the greatest barriers to the healthy development of art interest in America is unquestionably the fact that it has been so largely cultivated hitherto as an interest peculiar to women.” Barr believed that an American market for modern art would not come into existence unless successful businessmen became involved.38

Art consumer preferences as revealed by the data sample divide along gender lines with respect to form.39 Women were drawn to painterly abstraction, while men’s choices showed a preference for figurative works that more often than not emphasized line and clarity. Despite this remarkable preference for disegno in the market, the critical and art historical discourse that emerged around Pop Art ignored the formal aspects of the new style, and focused on its provocative content only. This is all the more surprising since “significant form” had been established as the “essential quality” of works of modern art early in the twentieth century and governed art historical interpretation. Heinrich Wölfflin provided the tools for such formal analysis in his seminal work The Principles of Art History in 1915, in which he showed that Renaissance works of art can be defined using five formal principles: a linear rendering of forms, a planar composition in which forms are placed parallel to the picture plane, a composition that is closed and refers only to itself, multiplicity or the arrangement of independent parts within the picture, and, last, the absolute clarity of the picture itself. One only needs to think of Andy Warhol’s soup can paintings to realize that many Pop works share these Renaissance characteristics.

Remarks by male collectors themselves support this gendered view of the shift in tastes, echoing Lichtenstein’s understanding of Pop’s appeal as the embodiment of the new and bracing visual impact of postwar business practices on society. Similarly, the American collector Leon Kraushar nailed the Pop “mood” in this colorful (and misogyny-inflected) appraisal: “All that other stuff – it’s old, it’s old, it’s antique. Renoir? I hate him. Cézanne? Bedroom pictures. It’s all the same. It’s the same with the Cubists, the abstract expressionists, all of them. Decoration. There’s no satire, there’s no today, there’s no fun. That other art is for the old ladies, all those people who go to auctions – it’s nothing, it’s dead. Pop is the art of today, and tomorrow, and all the future.”40

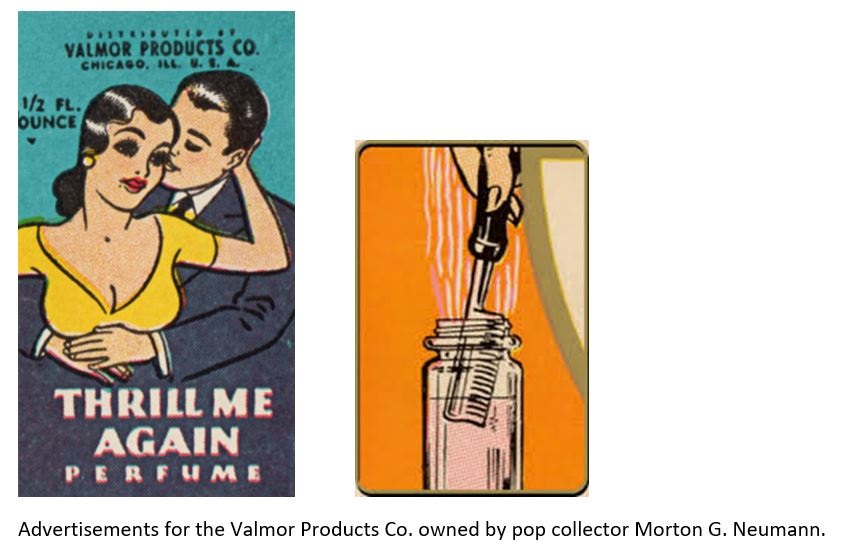

Like the Renaissance merchants in fifteenth-century Florence and the dry goods merchants in nineteenth-century America,41 Pop’s collectors almost certainly were drawn by the alignment between their business interests and the aesthetic and iconography of the works they purchased. The absolute clarity provided by line and illumination, which governed the commercial imagery that suffused American mass culture, was adopted by the Pop artists, who, after all, borrowed liberally from advertising. The aesthetic can be construed as a kind of new disegno – a mimetic realism of the new “nature” embodied in the business world. However, this interpretation has been sidelined by Pop scholarship’s preoccupation with content rather than form. For example, Cécile Whiting focuses on Pop Art’s “appropriation of those aspects of consumer culture associated with women – feminine spaces, feminine motifs, or feminine viewing practices”42 while Sara Doris links Pop to the “anxieties produced by the erosion of older social hierarchies, the emergence of a rebellious teen culture, and the popularization of gay taste.” These together, she argues, “provided the basis for pop’s transcendence of high-modernist cultural norms.”43 Neither scholar entertains the possibility that Pop Art’s popularity may have had its origin both in its stylistic features and in the acceptance of the works by the producers of mass culture – businessmen such as Morton G. Neumann, a major collector of Pop Art, whose advertising for hair products in the 1950s, bears strong similarities to the Pop works that followed (see Figure 2 and 3).

Bourdieu’s observation of intergenerational cultural amnesia points toward the answer to the key question of how the businessmen-collectors of Pop Art acquired the knowledge that enabled them to discern its merits. We need only reflect on the tastes of previous generations of businessmen-collectors. Even as the American art world was embracing the sophisticated arguments made for the French and American modern painting, the popularity of paintings by the great masters of the Italian Renaissance had endured. Many of the late nineteenth-century American millionaires had embraced the ideals of the Italian Renaissance both in art and business. Renaissance masterworks, especially those by Raphael,44 were considered the crowning pieces of private art collections. At the same time, Renaissance architecture, with its fondness for Greek temple designs, became the preferred style for commercial buildings such as banks and offices. This preference did not escape dealer Sidney Janis, who, in 1964, mounted an exhibition titled “The Classic Spirit in 20th Century Art”, in which he situated contemporary hard-edge painters such as Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella within the “classic” tradition.

Fig. 2: Advertisement for the Valmor Products Co., owned by pop collector Morton G. Neumann

The idea that Pop Art in effect redeployed the same formal aesthetic principles that powerful American businessmen had prized since the nineteenth century would suggest, surprisingly, that the brash male consumers of lowbrow Pop were actually staunch traditionalists in matters of content and form, and simply remained faithful to the loftiest Renaissance ideals. This is one among the many shifts and paradoxes that emerge from my admittedly unorthodox use of data analysis. Pop’s success, I contend, marked what can be viewed as a certain masculinization of the art market, in that the very existence of a true market required the big money the businessmen-collectors brought in. But I am also referring to an important shift in energies and values implied in art collecting in the United States during the first half of the twentieth century, which were inflected by gender. The activities of the high-profile women educators and philanthropists in an earlier era, and to an extent even the nurturing female gallerist-patrons that succeeded them, were underpinned by assumptions about the disinterested nature of art and the ennobling virtues of good taste. Forget all that, said the new male collectors, this is really about the money, about investment. The irony, of course, is that Pop Art, like prior shocking iterations of the avant-garde, was eventually legitimated by highbrow culture and absorbed into sanctioned taste categories. The savvy businessman-collectors of Pop could see it as simultaneously a gamble on the avant-garde and a blue-chip investment.

Titia Hulst is the editor of A History of the Western Art Market, A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets (September 2017). The above article is based on her book on the art dealer Leo Castelli, to be published by the University of California Press in 2018.

1 Alessandra Stanley, Can 50 Million Frenchmen Be Wrong?, in New York Times, 21 October 1990.

2 As suggested by Serge Guilbaut’s How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985). While Guilbaut refers to the ascendency of Abstract Expressionism in cultural and geo-political terms, he does not address the market for the new American style, which lagged significantly behind its critical success.

3 See for example Hiroko Ikegami, The Great Migrator: Robert Rauschenberg and the Global Rise of American Art (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010), 58, and Laurie J. Monahan’s essay Cultural Cartography: American Designs at the 1964 Venice Biennale in S. Guilbaut, ed., Reconstructing Modernism: Art in New York, Paris, and Montreal 1945-1964 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990), 369-416.

4 Alan R. Solomon, ‘Report on the American Participation in the XXXII Venice Biennale, 1964’. Alan R. Solomon Papers, Jewish Museum Archives.

5 Fernand Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce - Civilization and Capitalism: 15th-18th Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), 90–91.

6 As Alain Jouffroy wrote to Ileana Sonnabend, a dealer of Pop art in Paris: “Devant le front américain que vous avez réussi à créer sous le chapeau du Pop Art, il n’y avait évidemment en Europe que des individus, des libertés séparées. Votre union apparente a créé l’illusion de la force, nos divisions ont laissé croire à notre faiblesse car les individus ne peuvent s’imposer aujourd’hui que s’ils sont soutenus, vous le savez mieux que personne...mon rôle de propagandiste n’a jamais été et ne sera jamais le mien pour personne. D’ailleurs, serait-il le mien que vous n’en auriez plus besoin: le Pop Art a triomphé, malgré les résistances et a même béneficié de ces résistances.” Alain Jouffroy, letter to Ileana Sonnabend, November 30, 1964. Castelli Gallery Papers, Archives of American Art, Box 11 folder 70.

7 Hayden Herrera, Postwar American Art in Holland, in Rudi Fuchs and Adam Weinberg, eds., Views from Abroad/Amerikaanse Perspectieven (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, distributed by H.N. Abrams, 1995), 38. See also the introduction by Fuchs.

8 Paul Ardenne, The Art Market of the 1980s, in International Journal of Political Economy 25/2 (1995), 106.

9 Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 2.

10 A perfect example of such socially exalted collectors is the Rothschild family, whose lavish taste became known as “le goût Rothschild,” which became the preferred style for the newly wealthy American industrialists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, who were seeking social capital. Frederic Morton, The Rothschilds: A Family Portrait (New York: Diversion Books, 1961), 7.

11 Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction, 1.

12 http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/815597/remembering-herbert-vogel-the-postman-who-amassed-one-of-americas-greatest-art-collections/page/0/1. Accessed on 10 March 2017.

13 Matt Schudel, Herbert Vogel, unlikely art collector and benefactor of National Gallery, dies at 89, in Washington Post, 22 July 2012.

14 Thomas Crow, The Practice of Art History in America, in Daedalus 135/2 (2006), 76.

15 Michael Leja, Looking Askance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 134.

16 Andreas Huyssen, Mass Culture as Woman: Modernism’s Other, in Andreas Huyssen, After the Great Divide: Modernism, Mass Culture, Post Modernism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 47, 48.

17 Clive Bell, The Aesthetic Hypothesis, in F. Frascina and C. Harrison, eds., Modern Art and Modernism (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987), 70.

18 See Christine Battersby, Gender and Genius (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990).

19 Emile Zola, Edouard Manet, in F. Frascina and C. Harrison, eds., Modern Art and Modernism (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987), 29-30.

20 Maurice Denis, Cézanne, in F. Frascina and C. Harrison, eds., Modern Art and Modernism (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987), 57, 63.

21 While the total number of sales transactions in the primary market in this period cannot be known, the nearly 20,000 transactions can be considered a robust sample according to statisticians I consulted.

22 In order to detect statistically valid differences, the absolute data captured in the database were recalculated as percentages for statistical analysis. Differences between groups and subgroups in the sample were calculated at a 95 percent confidence interval. In other words, when discussing differences between groups, I am 95 percent certain that these are meaningful.

23 Michael Leja, Reframing Abstract Expressionism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 256.

24 T.J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 304.

25 T.J. Clark, Farewell to an Idea, 305.

26 Kathleen L. Housley, Emily Hall Tremaine: Collector on the Cusp (Meriden, CT: Emily Hall Tremaine Foundation, 2001).

27 Anna C. Chave, Minimalism and the Rhetoric of Power, in Arts Magazine. 64/5 (1990), 44-63.

28 Rona Joffe, Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 316.

29 Max Kozloff, Pop Culture, Metaphysical Disgust, and the New Vulgarians, in Art International 6/2 (1962), 34-36.

30 Peter Selz, Pop Goes the Artist, in Partisan Review 30/3 (1963), 316.

31 Gene R. Swenson, What is Pop Art? Answers from Eight Painters, in Art News 62/7 (1963), 25.

32 Michael Baxandall, Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), 29-108.

33 Quoted in Catherine Dossin, Pop Begeistert, in American Art 25/3 (2011), 105.

34 Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of Americans (London: Whittaker and Teacher Co., 1832). Emphasis added.

35 Henry James’s The American (1877) sketches a convincing portrait of such cultural innocence. See also S.N. Behrman, Duveen (New York: Random House, 1952) for other examples, including the story of the H.E. Huntington’s 1921 purchase of Gainsborough’s Blue Boy (1779), 197-205.

36 Russell Lynes, The Tastemakers (New York: Dover Publications, 1980), 331.

37 Meyer Schapiro, The Introduction of Modern Art in America: The Armory Show, in Meyer Schapiro, Modern Art, Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries: Selected Papers (New York: George Braziller, 1978), 162.

38 A. Deirdre Robson, Prestige, Profit, and Pleasure (New York: Garland, 1995), 70.

39 It is unfortunate that Komar & Melamid’s “People’s Choice Project” (1994), a broad survey of taste in the United States, did not break out gender preferences.

40 You Bought It, Now Live with It, in Life, 16 July 1965.

41 See Baxandall, Painting and Experience, and the chapter on the audience for William Harnett’s trompe l’oeil paintings in Michael Leja, Looking Askance (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004).

42 Cécile Whiting, A Taste for Pop (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

43 Sara Doris, Pop Art and the Contest over American Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 14.

44 David Allan Brown, Raphael and America (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1983), 31.