ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Jan Hüsgen

The acquisition of objects during exploratory/military missions was an important source for the formation of ethnographic collections. The focus of the paper is a systematic analysis of the modes of collecting during the “Togo Hinterland Expedition”. Several items that had been acquired on it found its way into mayor ethnographic museum collections (Berlin, Leipzig). Their acquisition has not yet been considered in their colonial context.

The “Togo Hinterland Expedition” of 1894/1895 was intended to repel French and British colonial interests by extending the German colonial power upriver along the Niger. Therefore, the primary task of the exploratory/military mission was to enforce German rule through the signing of treaties and/or the exercising of punishment against the local population. Another goal of the expedition was the scientific exploration of the northern territories of the German colony. Consequently, one of its members, Ernst Baumann (1871-1895), who had been educated in ethnography and natural history in Berlin, was responsible for the collecting of several items that were later displayed from the colonial exhibition in Berlin (1896).

The “Togo-Hinterland Expedition” has already received attention by researchers due to its importance for the political history of the German colony Togo. This article has a different focus, taking a closer look at the acquisition of ethnographic objects during the expedition, based on the rich documentation by its members, in the form of memoirs, reports to the colonial office and letters to museum officials. A vast range of different forms of collecting can be observed, ranging from legal acquisition to plundering. Furthermore, the article aims to analyse the modes of action of the different parties involved in the process within the colonial context of exploratory/military expeditions.

In 1896, the Erste Deutsche Kolonialausstellung in Treptower Park in Berlin intended to present life in the colonies in the form of a large-scale exhibition, in order to convince its visitors of the colonial idea.1 The exhibition area allowed them to walk through a panorama of the German colonies. Settlements from East Africa, Cameroon, Togo and New Guinea were reconstructed and inhabited by people from the colonies. The exhibition area was equipped with wall charts that presented objects collected in the colonies, providing visitors with an ethnographic display of the material living conditions of people in German colonial dominions.2 The objects displayed in the exhibition came from various sources, among them private collectors, missionary societies and colonial expeditions.

The acquisition of objects during exploratory/military missions was an important source for the formation of ethnographic collections. The focus of the current article is a systematic analysis of the modes of collecting by colonial officials in the context of the “Togo-Hinterland expedition”. The objective of this expedition of 1894/1895 was to repel French and British colonial interests by extending the German colonial power upriver along the Niger. Therefore the primary task of the explanatory/military mission was to enforce German rule through the signing of treaties and/or the exercising of punishment against the local population. Another goal of the expedition was devoted to the scientific exploration of the northern territories of the German colony. Therefore, its members were educated in ethnography, geography and natural history. The results of their research were later published at length.3 Several items that had been acquired in the course of the expedition found their way into ethnographic museum collections. However, so far their acquisition has not been considered within their colonial context.

The “Togo-Hinterland expedition” already received attention by researchers due to its importance for the political history of the German colony of Togo. This paper has a different focus, taking a closer look at the acquisition of ethnographic objects during and within the context of the expedition, based on the rich documentation by its members, in form of memoirs, reports to the colonial office and letters to museum officials.4 A vast range of different forms of collecting can be observed, ranging from legal acquisition to plundering. Furthermore, the article aims to analyse the modes of action of the different parties involved in the process. By doing so, the article offers an analysis of the various forms of collecting within the colonial context of explanatory/military expeditions.

Fig. 1: Collection of ethnographic objects in Kpandu, Togo, in Meineke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahr 1896, 249

The formal establishment of German colonial rule in Togo began in 1884 with protection treaties concluded by Gustav Nachtigal on behalf of the German Reich.5 The following years were characterized by a gradual expansion of the German presence into the hinterland of the emerging colony. However, up to the 1890s there was no strong presence of German colonial administration, apart from the coastal region. Due to a lack of military power, the colonial administration was not in a position to intervene in social and political matters. The establishment of the Misahöhe station in 1890 meant a substantial expansion of the colonial power’s presence in the backcountry.6 Initially permanently occupied by one colonial official, the station had the purpose of serving scientific observations, as well as “combating English influence” and advancing trade routes to Lome.7 In the context of various “research expeditions” to northern Togo from the beginning of the 1890s, its foundation can be seen as a strategic facility for the consolidation of German rule. Scientific goals were often used as an excuse to disguise the true extent of colonial occupation and also to requisition funds for scientific research of the colonies for strategic military purposes.8

This primarily strategic orientation of German colonial policy as an instrument for establishing colonial rule also becomes clear when we look at the terminology. Of central importance for the example given here are the terms “expedition” and “hinterland”.

The so-called “expeditions” mostly served not only for the scientific exploration of areas that were uncharted from a European point of view, but also had a strong military component since they were supposed to achieve the enforcement of colonial rule. This is also evident in the example of the “Togo Hinterland Expedition” with its numerous attempts to conclude friendship and alliance treaties or to intervene by force in the event of resistance.

A further indication of the political dimension of the expedition can be derived from the use of the term “hinterland”. In the context used here, it is to be understood as a term of international colonial law, a part of international law of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that regulated relations among colonial powers. In this sense, “hinterland” refers to that part of the country to which the state authority already had access without having already subjected it legally. Typically, this referred to the interior of a country beyond the initially conquered or purchased coastal strips. If colonial possessions of one country were to be respected by the government of another, it was not sufficient for a region to be merely formally seized, e.g. by raising a flag, rather, it was necessary to exercise actual rule over the territory to be occupied.9

This also applies to the so-called “Togo Hinterland expedition”, which was financed in part with funds from the Africa Fund established in 1878.10 According to Peter Sebald, the Togo Hinterland expedition only ostensibly had scientific goals.11 The main aim of the expedition was to expand German colonial rule in the western and northern regions of the country. By establishing bases in strategically favourable locations and signing alliances, power was to be secured and French and English influences pushed back. Led by the German colonial officer Dr. Hans Gruner (1865-1943)12 and accompanied by his colleagues Richard Doering (1868-1939)13 and Ernst von Carnap-Quernheimb14 (1863-1945), the expedition set off from Lome on 17 October 1894 with twenty-five soldiers and one hundred and twenty-nine porters. Their route led them over the station Misahöhe to Kete-Krachi and from there further over Salaga to Jendi. The expedition finally reached the river Niger in February 1896. It had penetrated far into areas beyond the formal German colonial rule and had attempted to tie rulers to the German Reich through alliance treaties.

Even though it was emphasized in public that this would be a scientific expedition, the actions of those involved clearly demonstrate that this was primarily a matter of expanding and consolidating German colonial rule. This was already apparent at the outset when the expedition made an example of the priest of the influential Dente-Shrine and sentenced him to death in Kete-Kratchie. The plan to remove the priest had already been established before the beginning of the expedition. The politically influential institution of the Dente whose influence reached far into the area of the Gold Coast Colony was in conflict with German colonial interests. Numerous studies have attempted to analyse the background to the actions of the German colonial power. Donna Maier Weaver argues that struggles between the traditional authorities and Muslim settlers on taxation issues were of crucial importance.15 The long-term consequences of German colonial rule in the region were recently studied by Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu, who points out that struggles between the Dente priest and the Germans over market and ferry taxes might have been the reason for his execution.16 The perspective of the colonial metropolis was analyzed by Peter Sebald who maintains that this execution was used to make an example of German colonial power in northern Togo.17 According to Sebald it would have been unlikely that the Bosomfo accepted the ordinances of a German colonial official; especially as he represented a relatively unknown power in the region.18 In the aftermath of the event, the important trading point was developed into a German base, enabling the colonial government to try and control trade to the coast.

As shown, the focus of the expedition was not solely scientific research of the northern areas of the colony of Togo. However, in his memoirs Hans Gruner points out that he and his colleagues were engaged in the collection of scientific and geological objects as well as in a geographical survey of the country. The results of this research were to be used “in accordance with the public colonial interest”.19 The collections acquired in the context of the expedition became the property of the German Togokomité, which had to decide on their future location. Adverse circumstances, such as a reduction in porters due to illness, led to the loss of a large part of the collected objects. But where did the objects that were presented at the colonial exhibition in Berlin as a result of the Togo Hinterland expedition come from? To answer this question, it is worth taking a closer look at the individual actors and their role as producers of colonial knowledge.

Recently, the role of merchants, missionaries, military and colonial officials as contributors to networks of knowledge production has come increasingly into focus. Rebekka Habermas pointed out that colonial officials played an important role in the production of knowledge of the geography, botany, zoology and ethnography of the colonies.20 However, as explained above, these were not primarily “research stations” in a strict sense. In fact, the establishment of research stations invariably also served the aim of establishing colonial power. This becomes particularly clear when considering that colonial officials were also tasked with enforcing colonial order. On the one hand, colonial civil servants were certainly occupied with projects such as the geographical surveys of the country or the collection of botanical samples, but on the other hand they frequently exercised police authority and jurisdiction. This can also be seen in the example of the “Togo-Hinterland” expedition, in whose context punitive actions were carried out, as in the case of the priest of the Dente Shrine.

The scientific results of this expedition were linked with the name Ernst Baumann (1871-1895).21 Baumann had been sent to Togo by the German Foreign office and became deputy head of the Misahöhe station in 1893.22 Before joining the colonial service he had been educated in natural history and received insights into the collections from Togo in possession of the Ethnographic museum in Berlin.23 In the Deutsches Kolonialblatt he is often mentioned in connection with the scientific activity of the station Misahöhe.24 Here, Baumann was referred to as a “government botanist”, who regularly collected insects and sent specimen to the Königliches Museum für Naturkunde.25 He was also engaged in a regular exchange with Felix von Luschan, whom he asked for a list of possible desiderata for the Togo collection of the ethnographic museum.26 Consequently, his research results were not limited to the collection of ethnographic objects, but collections of natural history benefited from his activities to the same extent. This is also evident from the fact that his collection activities were honoured for both ethnographic and natural science in the catalogue of the colonial exhibition.27 Even though Baumann accompanied the expedition only up to Kete-Krachi, he was still significantly involved in the collection of ethnological objects in their surroundings. He used various methods that illustrate a broad range of actions for the acquisition of ethnographic objects. This will become clear when we take a closer look at the modes of collecting in the context of the “Togo-Hinterland” expedition.

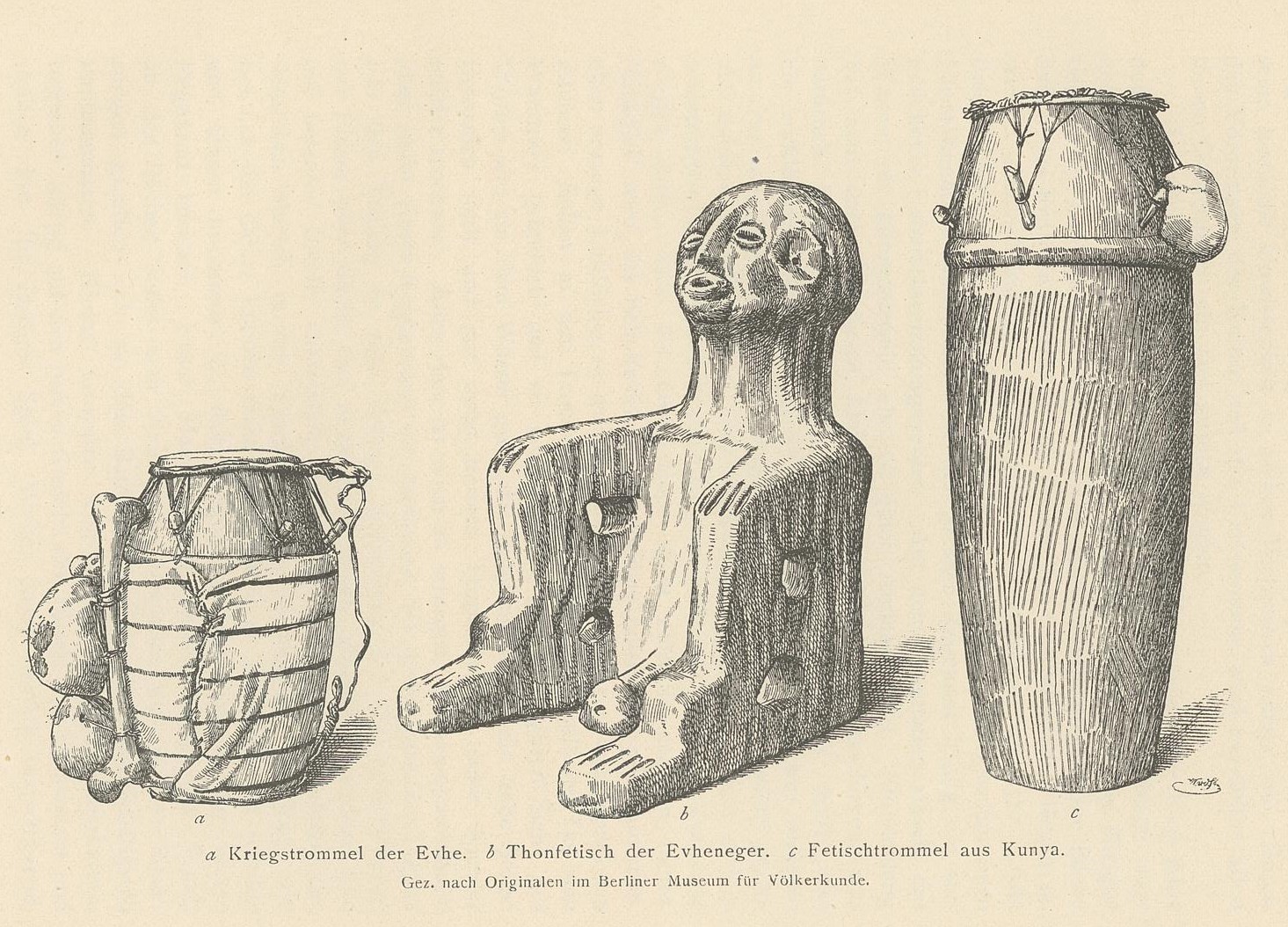

A common procedure for the acquisition of ethnological objects was their commercial purchase. In his efforts to acquire objects for the ethnological museum, Baumann had to become adept at lengthy negotiations and in dealing with high price expectations. This becomes particularly clear in the case of the acquisition of two so-called “fetish drums” which he tried to acquire in 1894 for the ethnographic museum in Berlin. In September of that year Baumann wrote to Karl Weule: “Because of the fetish drum I have already initiated the necessary steps, but the thing will become expensive, I think under 5-6 pounds of English currency I will not get away but the acquisition refers to a very rare, in later years hardly to be recovered piece.“28

Baumann justified the anticipated high price by emphasizing that these were particularly rare pieces that would be difficult to acquire later. He tried to purchase this piece through direct negotiations with the “fetish priests”. In fact, his account from April 1894 shows that he paid eighty marks for a fetish drum from Nkonya, with sixty marks directly paid to the ruler of Nkonya and twenty marks to the “fetish priest”.29 In his comments on the acquisitions, Baumann expands on the circumstances as follows: “It was no easy task to get the drum, none of the surrounding tribes were allowed to know anything about the sale, it was taken out of the king‘s house at night and transported to the station unnoticed and as quickly as possible.“30

This example illustrates that, even within the colonial situation, the acquisition of ethnological objects sometimes had to take place within the general framework of the market. An acquisition might require lengthy and intensive negotiations in advance. In addition, it became apparent that resistance to significant objects being sold was to be expected, if the fact became known. This opposition was obviously taken so seriously that in this example the sale could only be carried out in secret.31

Other items that were labeled as part of the “Togo-Expedition” were acquired on public markets and did not require protracted negotiations. This was the case with a number of Ashanti weights that Dr. Gruner purchased during the expedition and later donated to the museum.32 These weights were among the pieces that were later presented to the public in the context of the colonial exhibition.33

In the catalogue of the colonial exhibition, so-called war drums decorated with human skulls attracted special attention. The human remains used to decorate the drums came from Ashanti warriors killed in wartime. They were highlighted in the catalogue in a detailed drawing and a photograph by F. Schänker.34 Baumann had tried to obtain such drums at the special request of Felix von Luschan. In September 1894 he pointed out that “At present I am in multiple negotiations for the procurement of a skull drum and I have hope to obtain one, albeit among a significant sacrifice of money.”35 Once again, his letter points out that the rarity of a piece has had a significant impact on its price. As they were hard to find, it took some time for Baumann to acquire such drums. In a letter to Karl Weule from April 1895 he pointed out, that „I acquired two war drums from Kpandu, each with 2 skulls and arm bones of slain Ashanti, through the generous friendship of King Dagadu, as well as the war pipe with human mandibles.“36

In the case of the skull drums, Baumann may have benefited from the fact that the king of Kpandu, Dagadu, wanted to show his loyalty to the German colonial power in the context of the Towe uprising.37 The so called Towe uprising, was the military subjugation by German troops in March 1895 of the settlements in the Towe Landscape. The German colonial forces then carried out a punitive action and destroyed villages and lands in the Towe region. Several neighbouring communities demonstrated loyality to the German colonial power and offered their support to defeat the insurgents.38 In some cases it is likely that communities instrumentalised the Germans in order to enlist assistanceagainst rivals.39 The people of Kpandu had also assured the German colonial power of their support. It seems likely that the acquisition of these rare and important pieces was only possible through direct mediation of King Dagadu. Whether he wanted to prove his generosity to the colonial power by selling these particularly rare objects cannot be finally clarified. However, it is important to point out that this was not just a gift, as Baumann paid a total of eighty marks for the drums and the pipe according to his bill.40 This at least suggests that he did not negotiate the sale of the objects with Baumann from a position of complete powerlessness.

Fig. 2: Ivory horn with human mandibles from Kpandu, Togo in Meineke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahr 1896, 258

In contrast with the acquisition of objects through purchases and as gifts there are also objects that were obtained through looting by German colonial officials. This applies in particular to objects that were acquired in the context of the Towe uprising and the execution of the “fetish priest” in Kete-Krachi.41 In the course of the punitive action in the Towe region, Baumann plundered ethnographic objects later sent to the Ethnological Museum. Since these were “captured” pieces, he did not list them at cost in his invoice to the Ethnological Museum, but only itemized the transport charges incurred.42 In his article Zum Fetischwesen der Ewe Karl Weule praised not only Baumann’s diplomatic abilities to acquire rare and exclusive objects, but also that he “knew how to use every opportunity to enrich the collections of the royal museum, even in times of warlike entanglements. During the uprising of the Towe people in March 1895 he captured a large number of clay and other fetishes, which he sent to the Museum für Völkerkunde as valuable evidence of West African idolatry.”43

Fig. 3: War drum from Kpandu, Togo in Meineke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahr 1896, 248

Weule’s article was largely based on Bauman’s description of the “campaign against Towe”.44 In his report Baumann explained how often the Toweer had already got into „disputes“ with the German colonial government and that this had “brought about the partial destruction of the tribe”.45 Baumanns description of the so called Towe uprising made use of a stereotyping and defamatory description of the Towe people. In the following passage Baumann listed the individual objects he was able to capture in detail, briefly describing their appearance and use.

Another act of looting of objects took place in the context of the execution of the “fetish priest” in Kete-Krachi. A letter from Dr Gruner of November 1896 points out that after the execution of the priest plundering obviously took place and that items taken were sent to the museum: “When I caught the fetish priest Mossomfo in Kratchie (at the beginning of the Togo expedition), I captured a number of valuable ethnographica (e.g. the priest’s fetish skirt [...] cap, fetish sticks, drumsticks etc. and other things).”46

Dr. Gruner handed these objects over to Baumann, who accompanied him as far as Kete-Krachi, so that he could arrange for them to be sent to Berlin.

Fig. 4: The destroyed village Tove-Djibe, in Klose, Togo unter deutscher Flagge, 160

The acquisition of the objects presented as results of the “Togo-Hinterland“ expedition took place in a phase of expansion of colonial rule in middle and northern regions of the German colony Togo. It is certainly true that the objectives of the “Togo-Hinterland“ expedition were only ostensibly scientific. The focus was on the presentation of the German colonial power and the expansion of its sphere of influence. The violent enforcement of colonial rule replaced a previously informal rule. This becomes particularly clear in the suppression of the so-called “Towé uprising“ and the execution of the “fetish priest” in Kete-Krachi.

Colonial officials played a central role in the acquisition of ethnographic and other objects and can therefore rightly be regarded as central actors in the transfer of knowledge. The examples examined clearly show how diverse the individual circumstances of the acquisitions were. In addition to commercial purchases and diplomatic gifts, the looting of objects can also be observed. However, the African side cannot be seen invariably as a powerless, passive actor, as the intensive and lengthy negotiations for the acquisition of particularly rare objects, for example, show. In the case of objects which were forcibly stolen, these plunderings were often preceded by acts of resistance against German rule.

Fig. 5: Objects acquired in the context of the „Togo-Hinterland Expedition“, in Heinrich Klose, Togo unter deutscher Flagge: Reisebilder und Betrachtungen (Berlin: Reimer, 1899), 304

Jan Hüsgen is a research associate in the department for cultural assets and collecting in colonial contexts at the German Lost Art Foundation.

1 A detailed documentation was published by Gustav Meinecke, ed., Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahre 1896. Amtlicher Bericht über die erste deutsche Kolonialausstellung (Berlin: Reimer, 1897). Recently the exhibition became the focus of an exhibition project by the district museum Treptow, the Initiative of Black People in Germany and Berlin Postkolonial e.v., cf. Zurueckgeschaut.de (13 October 2019).

2 Gustav Meinecke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahre 1896, 265-270.

3 Rebekka Habermas, Intermediaries, Kaufleute, Missionare, Forscher und Diakonissen. Akteure und Akteurinnen im Wissenstransfer, in Rebekka Habermas, Alexandra Pryzembel, eds., Von Käfern, Märkten und Menschen. Kolonialismus und Wissen in der Vormoderne (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013), 27-48, here 36f.

4 Peter Sebald, Hans Gruner, eds., Vormarsch zum Niger. Die Memoiren des Leiters der Togo-Hinterland Expedition 1894/95 (Berlin: Edition Ost, 1997). For an unpublished account by Dr. Richard Doering cf. Janosz Riesz, Der Bericht des Arztes Dr. Richard Doering (1868-1938) über seine Teilnahme an der Togo-Hinterland Expedition, in Katharina Inhetveen, Georg Klute, eds., Begegnungen und Auseinandersetzungen. Festschrift für Trutz von Trotha (Köln: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, 2009), 533-554.

5 Peter Sebald, Togo 1884-1914. Eine Geschichte der deutschen “Musterkolonie” auf der Grundlage amtlicher Quellen (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1988), 37f. Nicoue Gayibor, ed., Histoire de Togolais. Des origines aux anées 1960. Le Togo sous administration coloniale (Lome: Karthala et Presses de l’Université de Lomé, 2011), 23f.

6 Gayibor, Histoire de Togolais, 37.

7 Sebald, Togo 1884-1914, 87.

8 Bettina Zurstrassen, “Ein Stück deutsche Erde schaffen”. Koloniale Beamte in Togo 1884-1914 (Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2008, 26f. Trutz von Trotha, Koloniale Herrschaft. Zur soziologischen Theorie der Staatsentstehung am Beispiel des „Schutzgebiets Togo“ (Tübingen: Mohr, 1994), 69.

9 Alexander von Dankelmann, Hinterland, in Heinrich Schnee, ed., Deutsches Kolonial Lexikon 2 (1920), 68.

10 Hans Gruner, Vormarsch zum Niger, 19.

11 Sebald, Togo 1884-1914, 156, 161-167.

12 Hans Gruner, Vormarsch zum Niger, 17f.

13 Riesz, Der Bericht des Arztes, 533f.

14 Ernst Gerhard Jacob, Ernst Carnap-Quernheimb, in Neue Deutsche Biographie 3 (1957), 151.

15 Donna Maier Weaver, Competition for Power and Profits in Kete-Krachi, West-Africa, 1875-1900, in The International Journal of African Historical Studies 13 (1980), 33-50, here 42f.

16 Samuel Aniegye Ntewusu, The impact of German colonialism in Kete Krachi, North-Eastern Ghana, in African Studies Centre Leiden Working Paper 121 (2015), 4-6, 9f.

17 Sebald, Togo 1884–1914, 162f.

18 Ibid.

19 Hans Gruner, Vormarsch zum Niger, 28. “Daß die von den Gliedern der Expedition veranstalteten Naturalien- und sonstigen Sammlungen, sowie die kartographischen Aufnahmen nur eine, dem öffentlichen kolonialem Interesse entsprechende Verwendung finden dürfen.” (Author’s translation)

20 Rebekka Habermas, Intermediaries, Kaufleute, Missionare, Forscher und Diakonissen. Akteure und Akteurinnen im Wissenstransfer, in Rebekka Habermas, Alexandra Pryzembel, eds., Von Käfern, Märkten und Menschen. Kolonialismus und Wissen in der Vormoderne (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2013), 27-48, here 36f.

21 Wilhelm Heß, Ernst B. Baumann, in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, 46 (1902), 254f.

22 Karl Weule, Zum Fetischwesen der Ewe, in Ethnologisches Notizblatt 1 (1894/1896), 29-37, here 29 (Annotation 1).

23 Daniela Baumann, Exkurs: Der Togoforscher Ernst Richard Reinhold Baumann (1871-1895), in Jürgen Runge, Republik Togo. Geographische Einblicke zwischen dem Golf von Guinea und der Sudanzone in Westafrika (Aachen: Shaker Verlag, 2013), 71.

24 N.N., Togo. Thätigkeit der wissenschaftlichen Station Misahöhe, in Deutsches Kolonialblatt. Amtsblatt für die Schutzgebiete des deutschen Reichs V (1894), 74, “Regierungsbotaniker”.

25 Cf., ibid., Sammlung zoologischer Objekte aus dem Togogebiet, 191; Sammlung naturwissenschaftlicher Gegenstände, 344; Sammlung naturwissenschaftlicher Gegenstände, 555f.

26 SMB-ZA, EM 1469/1894, Ernst Baumann to Felix von Luschan, 29 September 1894.

27 Meinecke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahre 1896, 246-250, 311-317.

28 SMB-ZA, EM 950/94, Ernst Baumann to Karl Weule, 25 September 1894 “Wegen der Fetischtrommel habe ich die nöthigen Schritte bereits eingeleitet, aber die Sache wird theuer werden, ich denke unter 5-6 Pfund engl. werde ich nicht wegkommen aber die Erwerbung bezieht sich auf ein ganz seltenes, in späteren Jahren kaum mehr wiederzuerlangendes Stück.” (Author’s translation)

29 SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Karl Weule, 8 April 1895.

30 SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Karl Weule, 8 April 1895: “Es war kein leichtes Stück Arbeit die Trommel zu bekommen, keiner der umliegenden Stämme durfte etwas vom Verkauf erfahren, sie wurde des Nachts aus dem Hause des Königs geholt und unbemerkt und schleunigst nach der Station befördert. (Author’s translation)

31 Weule, Zum Fetischwesen der Ewe, 35f.

32 Cf. SMB-ZA, EM 23/96, Memorandum by Felix von Luschan, 7 January 1896.

33 Meinecke, Deutschland und seine Kolonien im Jahre 1896, 246.

34 Ibid., 247f.

35 SMB-ZA, EM 1469/1894, Ernst Baumann to Felix von Luschan, 29 September 1894: “Zur Zeit stehe ich in mehrfachen Verhandlungen wegen Beschaffung einer Schädeltrommel und ich habe Hoffnung eine solche, freilich unter bedeutenden Geldopfern, zu erlangen.” (Author’s translation)

36 SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Karl Weule, 8 April 1895: “Die beiden Kriegstrommeln aus Kpandu mit je 2 Schädeln und Armknochen erschlagener Ashanti erwarb ich durch die großzügige Freundschaft des Königs Dagadu, ebenso die Kriegspfeife mit menschlichen Unterkiefern.” Weule, Zum Fetischwesen der Ewe, 36.

37 Sebald, Togo 1884-1914, 169.

38 Ibid., 167-170.

39 Ibid., 169.

40 SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Adolf Bastian, 8 April 1895: “5. 2 Kriegstrommeln aus Kpandu Mk 60 [...] 15. Kriegspfeife aus Kpandu mit menschl. Unterkiefern Mk 20.”

41 The term “fetish priest” is a colonial term and historically used to describe practitioners of any kind of what was regarded at the time as a pagan ritual.

42 SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Adolf Bastian, 8 April 1895: “Transport der in Towe erbeuteten Gegenstände nach der Küste.”

43 Weule, Zum Fetischwesen der Ewe, 29: “[...] wusste er auch in Zeiten kriegerischer Verwicklungen jede sich darbietende Gelegenheit zu benutzen, die Sammlungen des königlichen Museums zu bereichern. So erbeutete er während des Aufstandes der Towe-Leute im März 1895 eine größere Anzahl von Thon- und anderen Fetischen, die er als wertvolle Belege westafrikanischen Götzendienstes dem Museum für Völkerkunde übersandte.”

44 Anlage 2, Aus dem Feldzug gegen Towé im März 1895, in SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Adolf Bastian.

45 Anlage 2, Aus dem Feldzug gegen Towé im März 1895, in SMB-ZA, EM 573/95, Ernst Baumann to Adolf Bastian: “Rauhe, rohe Sitten, Unbotmässigkeit und Lust und Gefallen an Händeln haben sie schon des öfteren seit der Besitzergreifung Togos durch Deutschland in Streitigkeiten mit der Regierung gebracht und die heutige teilweise Vernichtung des Stammes herbeigeführt.”

46 SMB-ZA, EM 1386/96, Hans Gruner to Felix von Luschan, 23 November 1896: “Als ich den Fetischpriester Mossomfo in Kratschie (zu Beginn der Togo-Expedition) gefangen nahm, erbeutete ich eine Reihe wertvoller Ethnographica auf (z.B. den Fetischrock des Priesters [....] Mütze, Fetischsticks, Trommelstöcke etc. und andere Dinge).”