ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Nick Pearce

The article focuses on the way in which the visibility of collectors of Asian art impacted upon popular culture of the inter-war period, particularly the novel, initiating a sort of symbiotic enhancement of the collector and their activities. Referencing actual collectors against their fictional counterparts offers an intriguing insight into character, motivation and the market for Chinese works of art at the time. The actual and fictional come together in an attempt to point up the visibility of artefacts from China that during the period from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century became somewhat familiar in the public mind. This period which lasted into the late 1930s was both one of a growth in knowledge and of opportunity with the familiar blue-and-white porcelain of the nineteenth century giving way to the unfamiliar: objects in a huge range of forms and materials and dating from as far back as China’s earliest civilisation. The two went hand in hand. Knowledge of what was collected by individuals and museums grew out of the increased availability of material that was flooding out of China and on to the international art market. Its visibility was the result of major exhibitions and the prominence of collectors whose flamboyance and eccentricity also gave rise to characters in fiction from whom their habits, personalities and situations were drawn. What they all have in common is what Arthur Conan Doyle lets Sherlock Holmes refer to as “collection mania in its most acute form”.

The period between about 1900 and 1937 witnessed the opening up of an international market in Chinese artefacts at a time when China was vulnerable to encroachment and, after 1911 with the fall of the last imperial dynasty, was in political, social and economic turmoil.1 During the post-WW1 decades the visibility of the country and its cultural history also stimulated an academic and popular interest in Chinese material culture of all types and periods, but particularly burial objects being unearthed through railway construction (bronzes, jades and ceramics), which initiated both legal and illegal excavations and the market circulation of collections formerly owned by the Chinese élite. These opportunities to “collect” ended only with the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, when access to China was severely curtailed.

In this paper I will not rehearse the particulars of this historical situation beyond noting that it enabled the emergence of a significant number of collectors internationally who took advantage of a China in chaos to obtain objects, many of which would form some of the most important collections of Chinese art worldwide. Instead I will focus on the way in which the visibility of these collectors impacted upon popular culture of the inter-war period, particularly the novel, initiating a sort of symbiotic enhancement of the collector and their activities. Referencing actual collectors against their fictional counterparts offers an intriguing insight into character, motivation and the market for Chinese works of art at the time. Indeed the eccentricity and flamboyance of a number of real collectors made them ideal material for the writers of fiction.

The fictional collector of Chinese art did not emerge suddenly in the first decades of the twentieth century. One early manifestation was penned by English poet, antiquarian and essayist Charles Lamb (1775-1834) and may be semi-autobiographical.2 In his short story, Old China, written in the 1820s, Lamb delights in the “...lawless, azure-tinctured grotesques, that under the notion of men and women, float about, uncircumscribed by any element, in that world before perspective”.3 This he sees in a set of extra-ordinary old blue china (a recent purchase).4 (Fig.1). While taking tea, Lamb reflects upon his good fortune, remarking “...how favourable circumstances had been to us of late years, that we could afford to please the eye sometimes with trifles of this sort...”5 It was not always the case, where in the past there was a financial sacrifice involved in buying a piece of china. While the essay is a complex vehicle for musings on gender, the past and the passage of time and “Through the china teacup, we can enter into an imaginative world which promises freedom, civility and timeless good nature”, it also assumes a readership at the time that was familiar with both Chinese blue and white porcelain and the pleasures involved in collecting and using it.6

Fig.1: Cup and Saucer, porcelain painted in underglaze cobalt blue, Chinese, Kangxi period (1662-1722), Salting Bequest. ©The Victoria & Albert Museum.

The blue and white theme carried over into the later nineteenth and first part of the twentieth century with the revival of interest in Britain for seventeenth-eighteenth century porcelains, predominantly of the Kangxi period (1662-1722). Originally brought to Europe, especially Holland, more than a century or more before, the best pieces are characterised by a dazzling white porcelain body decorated with a vivid sapphire-blue cobalt (see Fig.1).7 Gerald Reitlinger suggests the revival was due to the interest of Anglo-American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903): “Seldom in the course of art history has it been possible to trace a taste of truly universal appeal to a single man or woman. Mme de Pompadour and her mounted Chinese monochromes may be an instance. Should the painter Whistler and his blue and white hawthorn vases be considered another?”8 Reitlinger’s conclusion is: “Yes. In 1863 Whistler was apparently a lone buyer, but in 1880 the pieces which he had sold to his few patrons had already reached the £1000-mark, and the craze did not end until after the First World War.”9

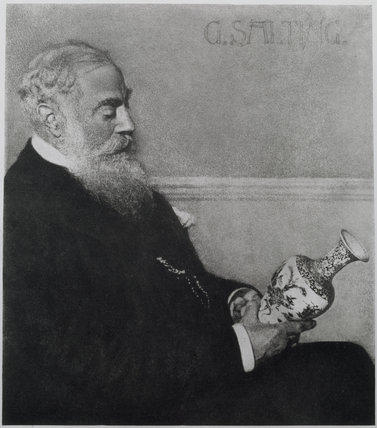

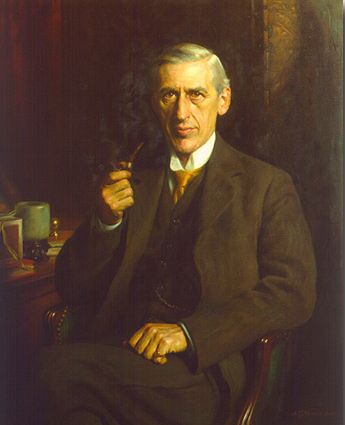

One collector who pursued the taste for Kangxi period porcelains was George Salting (1835-1909) (Fig.2). Salting had both wealth and eccentricity – the latter characteristic defining him in the public mind and for at least one celebrated author.10 Born in Australia, Salting inherited a considerable fortune from his father which had been built upon sugar growing and sheep farming. After attending Eton and then Oxford, the young George settled in London and began collecting a range of European and East Asian works of art, but particularly Chinese porcelain, building a massive collection which he first loaned and then bequeathed to the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) in 1909.11 Influenced by another collector, Louis Huth (1821-1905), Salting developed considerable knowledge and taste, so that at his death, not only the V&A, but also the National Gallery and the British Museum in London benefitted from his generosity. As well as blue and white, Salting also favoured so-called famille verte, famille rose and famille noire enamelled porcelains, all of which there are acres in the V&A. Despite his income of £30,000 a year, Salting was something of a recluse, lacked vanity and lived very modestly in two rooms above the Thatched House Club in St James’ Street, London. Collecting was his passion, and his abstemious and miserly ways were well known, as were, paradoxically, the generosity of his loans to museums, most notably the V&A. At his death and immediately afterwards he featured rather frequently in the press, particularly when the terms of his bequest were made public, although his collection on loan to the V&A had been the subject of a number of articles previously.12 His obituary in The Times provided enough biographical material for any novelist, pointing up his eccentricities and collecting practices.13 In the days following his death the importance of his collection was debated in the press as was speculation over its final destination.14

Fig.2 : George Salting (1835-1909), reproduced in Art Treasures Saved to the Nation, The Literary Digest, January 15, 1910, 103.

There can be no doubt that Salting’s personal eccentricities, collecting habits and way of life formed the basis of Vita Sackville-West’s (1892-1962) Mr FitzGeorge in her 1931 novel, All Passion Spent. An associate of the Bloomsbury Group which included critic, artist and commentator on Chinese art, Roger Fry (1866-1934), she would have been familiar with Salting and his collection (Fig.3).15 Surprisingly, no one seems ever to have linked the character of her fictional art collector with that of George Salting, who is undoubtedly her model. A clue to his identity is contained in his name, which is a combination of Salting’s first name, George, with the prefix, Fitz, which Sackville-West likely derived from one of Salting’s close friends and fellow collector, Joseph Henry Fitzhenry (1836-1913).16 Fitzhenry was a patron of the V&A, a well-known figure in the London art scene and an associate of Salting. In the novel, octogenarian Lady Slane, widow of a diplomat, re-acquaints herself with the elderly Mr FitzGeorge, whom she had first met in India decades before, but who is also a friend of her son, Kay Holland, himself a collector.17

Fig.3: Vita Sackville-West (1892-1962), photograph by Howard Coster, c.1927. © National Portrait Gallery,

London.

We meet FitzGeorge first in the company of Kay, who provides a description of his friend. It can be likened to George Salting: “FitzGeorge could buy anything he liked, but such was his eccentricity that he lived like a pauper in two rooms at the top of a house in Bernard Street, and took pleasure in a work of art only if it had been his own discovery and a bargain.”18 We also learn that his collection is “...coveted by the British and South Kensington Museums alike.”19 Further revelations about his habits follow:

...he kept his treasures close round him; the few people privileged to visit him in his two rooms came away with a tale of Ming figures rolled up in a pair of socks, Leonardo drawings stacked in the bath, Elamite pottery ranged upon the chairs. Certainly during the visit one had to remain standing, for there was no free chair to sit on; and jade bowls must be cleared away before Mr FitzGeorge could grudgingly offer one a cup of the cheapest tea, boiling the kettle himself on the gas ring. The only visitors to receive a second invitation were those who had declined the tea.20

Mr FitzGeorge had a high opinion of his collection:

My collection is, I suppose, at least twice as valuable as Eumorphopoulos [sic], and twice as famous – though, I may add, I have paid a hundredth part of its present value for it. And, unlike most experts, I have never lost sight of beauty. Rarity, curiosity, antiquity are not enough for me. I must have beauty or, at any rate, craftsmanship. And I have been justified. There is no piece in my collection to-day which any museum would not despoil its best show-case to possess.21

At FitzGeorge’s death, it is the V&A who alerts the police and who sends a junior curator to his home following forty years of hints that he would bequeath his collection to the nation: “His hints were pretty clear”, says the curator, “And if he hasn’t left it to the nation, who could he leave it to?”22 In real life, Salting did leave his collection to the nation (much to the chagrin of Australia), but in the novel, Vita Sackville-West diverges from real life. FitzGeorge leaves his collection to Lady Slane.

Fig.4 : George Eumorfopoulos (1863-1939), from Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 1939-40.

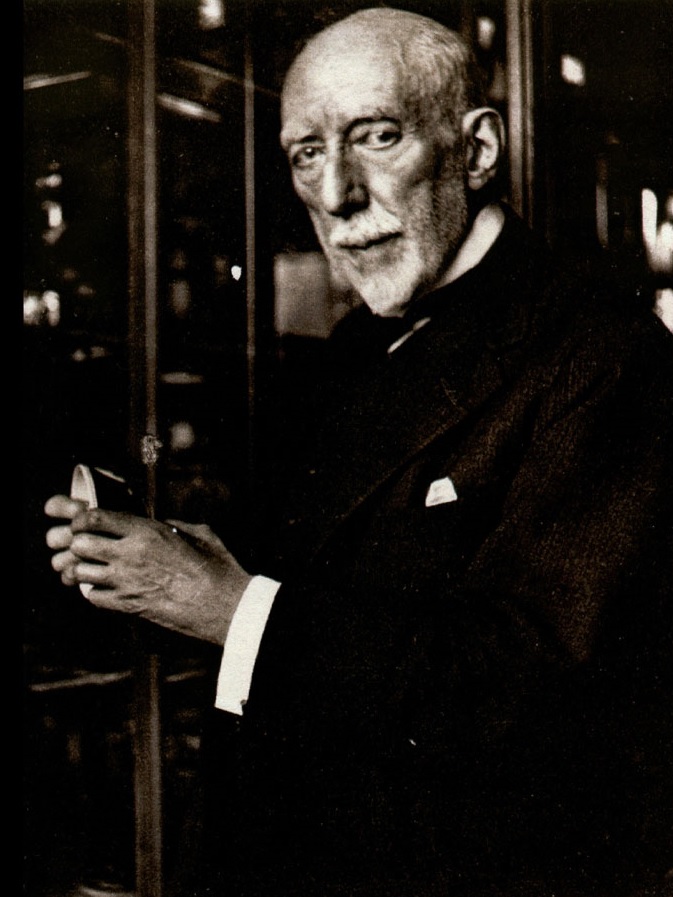

Artistic licence allows Sackville-West to conflate the generations too. FitzGeorge compares his collection to Eumorfopoulos (misspelt by Sackville-West) – a real-life collector of a generation later and of a very different kind of Chinese art. George Eumorfopoulos (1863-1939), was a wealthy London banker of Greek origin who built an exceptional collection of predominantly Chinese art, but also Japanese, Near Eastern and contemporary European ceramics during the inter-war years (Fig.4).23 He was part of a group of collectors during the 1910s, 20s and 30s, who took advantage of the mass of Chinese works of art which were coming out of China post the 1911 revolution and its instability. In contrast to Salting, the Eumorfopoulos collection was dominated by newly discovered archaeological objects such as ritual bronzes, jades and early burial ceramics and the sculpture, paintings and pre-eighteenth-century ceramics in former Chinese imperial and private collections: in fact objects that presented the full panoply of Chinese art as we know it today (Fig.5).24

Fig.5: Figure of a Bactrian Camel and Rider formerly in the Eumofopoulos Collection, earthenware with sancai glaze, Chinese, Tang Dynasty, 8th century. ©The Victoria & Albert Museum.

The archaeological discoveries were the result of railway construction which cut a swath through many of the provinces of northern China that had been at the heart of the cultures of the Neolithic and Bronze Age. China’s weakened position, particularly after the collapse of the imperial dynasty, allowed for legal, but more often illegal, excavations to take place, enabling the thriving art and antiquities market in China to feed a growing international appetite for wares largely unknown in the West and to a significant extent within China. Combined with a country riven by civil war and economic stagnation, private and even imperial collections were ripe for dislocation. At the height of this international market, Bernard Rackham (1876-1964), could write with imperialist hauteur:

Western connoisseurs were not slow to recognise the opportunities thus afforded of surrounding themselves with works of beauty of a kind until then almost wholly unknown to them, and the plundering activities of those who cater for their tastes threatened to leave China, like Greece, Egypt and other homes of ancient civilization, stripped almost bare of their finest works of her craftsmen of old.... Deplorable as, from some points of view, this turn of events might seem, it has seemed at times doubtful whether these treasures of ancient art would be as carefully and safely preserved in China itself as they are in the hands of Western collectors and museums.25

George Eumorfopoulos intended to bequeath his collection to the nation – like Salting – but in the end because of financial set-backs following the 1929 financial crash and Great Depression, he sold his collection to the British Museum and V&A in 1934 at below market value. A public subscription was launched which raised the required £100,000 and both museums benefitted hugely from the transaction.26

Eumorfopoulos was part of a generation of scholar-collectors who widened the scope of their collecting and researched the new material that was flooding the market. Indeed it has been argued that he and fellow collectors and museum curators that included R.L. Hobson (1872-1941), of the British Museum, the aforementioned Bernard Rackham of the V&A and collector Oscar Raphael (1874-1941), were in turn, through their collecting and writing, a stimulus to the market-shift to pre-seventeenth-century Chinese works of art and archaeology.27 These and eight other collectors founded the Oriental Ceramic Society (OCS) in 1921, the members of which in its early days met in each other’s houses.28 At the heart of their meetings was the opportunity to show and discuss their specimens and through museum curators Hobson and Rackham, to loan items to the V&A’s Loan Court on a rotating six-monthly basis, making the Society of service and visible to the wider public.29 Key members of the OCS were also instrumental in promoting and organising the International Exhibition of Chinese Art held at the Royal Academy in London in 1935-36, the first exhibition to include loans from China and Japan as well as North America and Europe.30

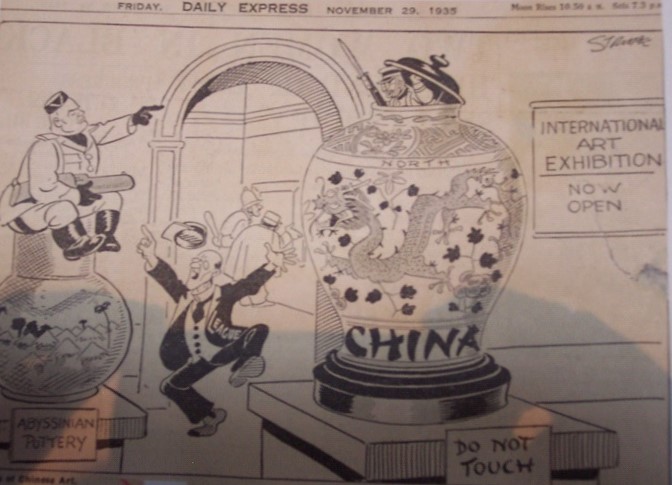

For China the Exhibition provided something of an international springboard politically and culturally, offering recognition of its internationalist credentials central to its membership of the League of Nations on the one hand and, as the major lender and co-organiser with Britain, acknowledgement of the struggling Nationalist government’s authority over its national treasures on the other.31 By 1935, China was not only fighting a civil war but also in conflict with Japan over Manchuria and northern China. The press were quick to use the pacific cooperation represented by the Exhibition to draw attention to Japan’s aggression against China, Italy’s earlier invasion of Abyssinia and the League’s powerlessness to intervene on both counts (Fig.6). Two years later Japan would declare war on China.

Beyond the politics, the Exhibition’s popularity was such that it had nearly 422,000 visitors with one out of every four patrons purchasing exhibition publications. In addition to having 3,080 exhibits and a lecture series, the exhibition organizers included a film series. The impact of the exhibition programming was carefully coordinated with the City of London, and in order to maximize and regulate attendance, pre-ordered railway tickets were discounted for school groups as well as for trades unions.32 The Exhibition was hugely influential, in academic, market and popular terms, making Chinese art and its collectors even more visible and in a sense marked the summation of the field before the onset of World War Two.33

Fig.6: “The Jap in the Vase”, cartoon by Sydney “George” Strube, Daily Express, 29 November, 1935.

The 1935 Exhibition was the largest and most international of a series of exhibitions that had showcased the arts of China since 1925, beginning in Amsterdam, organised by the Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (Society of Friends of Asiatic Art), followed by Cologne in 1926, again organised by the Freunde Ostasiatischer Kunst (Friends of Asian Art), with the largest, in Berlin in 1929, organised jointly by the Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst and the Preussische Akademie der Künste (the Society of East Asian Art and the Prussian Academy of Arts).34 All of these exhibitions had been organised by membership-based organisations. Many of those associated with the 1935 Exhibition (most particularly the collectors), were lenders to these previous shows, with members of the OCS in London being prominent among them. Whilst in 1921 the OCS had been restricted to a small group of wealthy business and professional men, post 1933 saw an increase in its membership, with a view to creating something close to the Verein , or learned society, on the German model, which had been the powerhouse behind the European exhibitions.35

Even at its inception the OCS included that shabby social set that aspired to the higher echelons of stratified British Society of the 1920s and 30s as reflected in Anthony Powell’s (1905-2000), novel, The Afternoon Men (1931). William Atwater in Powell’s novel, is a museum curator: “I guard some of the national collection”, he boasts to an unimpressed member of his circle of friends, Susan Nunnery, who has asked the question “do you collect then?”36 Atwater is very much like the real-life character of William August Henry King (1894-1958), a curator first at the V&A and then the British Museum, a specialist in European ceramics, who was chosen by the members of the OCS to be the Society’s Secretary, a position that seems to have come about through his museum position and his social connections (Fig.7).37 His languid, gentlemanly ways were summed up in his obituary in the Burlington Magazine:

For general ideas such as the art of ceramics in the abstract, he had little affection; the study of technique seemed to him plebeian; science and chemistry he abhorred. He seemed like a character who had strayed from the heights of Edwardian diplomacy into a narrower social sphere.38

His move to the British Museum in 1926 also reveals the importance of having social connections during this period. When another curatorial socialite William “Billie” Wilberforce Winkworth (1897-1991), son of collector, Stephen D. Winkworth (1864-1938, another OCS founder), whose attendance as a curator of ceramics at the British Museum under R.L. Hobson, was rather erratic, Hobson decided he had had enough and said: “I want King.” King was duly appointed.39 William King was also immortalised in a novel by another former curator turned writer at the British Museum, Angus Wilson (1913-1991), in his Old Men at the Zoo, where the Keeper of Birds, Matthew Price, was modelled on King, who was an old friend.40 For a brief period King could live the high life through an inheritance which he promptly squandered and like fellow British Museum curator, Campbell Dodgson (1867-1948), would turn up at work in a chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce.41

Fig.7: William Augustus Henry King (1894-1958), photograph by Bassano, c.1948. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

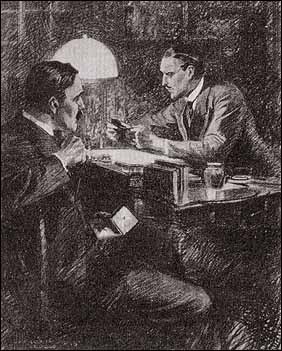

The mystery that is sometimes perceived to surround the collecting of East Asian art – its esoteric and exotic flavour, perhaps with a touch of darkness – combined with the intelligence often associated with those who collect artworks, provided Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) with a new protagonist for his detective, Sherlock Holmes. “The Adventure of the Illustrious Client” was one of Conan Doyle’s later short stories, providing the last casebook for Sherlock Holmes.42 First published in 1925, it was written just at the time when Eumorfopoulos and his fellow collectors were making an impact in the field of Chinese art in Britain. In the same way as Sackville-West, Conan Doyle would have been familiar with these collectors in the vanguard of growing knowledge, particularly as regards Chinese ceramics. In the story Baron Adelbert Gruner is an Austrian aristocrat with a past to rival Bluebeard. He is about to seduce a young heiress, Violet de Merville, the daughter of a military hero and to add her conquest and death to those of his previous women. Holmes has been consulted to prevent this being the young girl’s fate.

Baron Gruner is described by Holmes’ assistant and chronicler, Dr Watson, as having: “expensive tastes.... He collects books and pictures. He is a man with a considerable artistic side to his nature. He is, I believe, a recognised authority upon Chinese pottery and has written a book upon the subject.”43 “A complex mind”, observes Holmes, and adds admiringly, “all great criminals have that”.44 The Baron is also described as “extraordinarily handsome, with a most fascinating manner, a gentle voice and that air of romance and mystery which means so much to a woman.”45

Fig.8: “Very fine – very fine indeed!”. Baron Gruner examining a blue and white saucer. Original illustration by Howard K. Elcock, 1925.

It is Dr Watson who is set the task of gaining entry to Gruner’s home and this he does by posing as a collector who wishes to sell a set of early Ming blue and white saucers (Fig.8). Of a deep-blue colour and loaned by a collector for the deception, Holmes describes a saucer from the set which is to be the bait:

This is the real egg-shell pottery of the Ming dynasty. No finer piece ever passed through Christie’s. A complete set of this would be worth a king’s ransom – in fact, it is doubtful if there is a complete set outside the Imperial palace of Peking. The sight of this would drive a real connoisseur wild.46

First, however, Watson has to read up on the subject, through a visit to the London Library:

there I learned of the hall-marks of the great artist-decorators, of the mystery of cyclical dates, the marks of the Hung-wu and the beauties of the Yung-lo, the writings of Tang-ying, and the glories of the primitive period of the Sung and Yuan.47

Needless to say, Watson fails to convince the Baron of his credentials as a connoisseur, but does, with the aid of a jilted survivor, succeed in putting an end to the Baron’s conquests.

A real-life Watson would, by 1925, have had an increasing number of books to consult, not least a series of publications by R.L. Hobson, beginning in 1915, and with, appropriately, a volume on The Wares of the Ming Dynasty that was published in 1923.48 Watson makes reference to two emperors of the early Ming period: Hongwu (Hung-wu, r.1368-98) and Yongle (Yung-lo, r.1402-24), two periods renowned for high quality porcelain production and to Tang Ying (Tang-ying, 1682-1756), a Director of the Imperial Porcelain kilns at Jingdezhen during the first-half of the eighteenth-century, during whose period of office some of the finest porcelains of the Qing period were produced. His description of Song (Sung, 960-1279) and Yuan (1279-1368) wares as “primitive”, dates back to a classification made by nineteenth-century collector Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), in his book Le Céramique Chinoise, in 1894.49 By the 1920s this attitude was changing, with Song ceramics being designated “classic” wares, rather than primitive. So Conan Doyle, through the eyes of Watson, had done his homework, capturing within these descriptive lines some of the advances in knowledge of Chinese art by the second decade of the twentieth-century, and changing taste.

It seems unlikely that Conan Doyle was modelling his anti-hero, Baron Gruner, on a known collector of Chinese art. However, it has been suggested that his detective hero – Sherlock Holmes – was in part at least, modelled on one such collector. This was John Norman Collie (1859-1942), Professor of Organic Chemistry at University College London between 1902 and 1928, where he researched inert gases, constructed the first neon lamp, proposed a dynamic structure for benzene, and discovered the first oxonium salt (Fig.9).50 It was, however, his analytical mind together with his pipe-smoking and a shared life with a male companion (in Gower Street, rather than Baker Street), that were supposedly the elements borrowed by Conan Doyle for the creation of his famous detective.51

Professor Collie also had two other lives, equal to his scientific one: mountain climbing and collecting. He climbed most of the peaks in the Rockies and named half of them. He was part of the ill-fated 1895 Himalayan expedition, when A.F. Mummery (1855-1895) and two Ghurkas lost their lives and was one time President of the Alpine Club. Less discussed, has been Collie’s expertise in Chinese art, particularly porcelain and the collection he built.52 Yet Collie was a founder member of the OCS in 1921 and a lender to the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in 1935.53 Indeed the objects depicted in Arthur Trevethin Nowell’s (1862-1940) portrait of Collie, make clear above anything else, his connection with Chinese art. On the table is probably the jade brush-pot he loaned to the Exhibition in 1935, behind him is a screen and in the background we can just see the outline of two pieces of blue and white porcelain. In appearance, the figure in the painting could almost be of Holmes, but it is interesting that of all the attributes that Collie could have included in his portrait, he chose Chinese objects.

Fig.9: J. Norman Collie (1859-1942), by Arthur Trevethin Nowell, oil on canvas, 1927. Courtesy of the Sligachan Hotel, Isle of Skye, Scotland.

The interest in and market for early Ming porcelain was not only observed by Conan Doyle. John Phillips Marquand (1893-1960), was an American writer, best known for his short stories, articles for mass-circulation magazines and satirical novels of upper-class life in America. 54 However, in March 1934 he was sent to China by the Saturday Evening Post in Philadelphia with the purpose of gathering background material on a country that was front-page news and with the intention of creating a new character for his stories.55 The result was the Mr Moto spy novels set in China with a Japanese protagonist and Ming Yellow, an adventure story published first as a serial in the Saturday Evening Post and then as a novel.56 Marquand spent his time in Beijing and parts of northern China, including Manchuria, then of course occupied by the Japanese. While in Beijing he joined a number of other American socialites led by eccentric Metropolitan Museum of Art New York curator of Far Eastern Art, Alan Priest (1898-1969), who was on a collecting trip and George N. Kates (1895-1990), scholar, collector of Chinese hardwood furniture and commentator on life in Beijing during the 1930s (Fig.10). In 1933 Kates had set up home in an un-modernised traditional courtyard house and soon became fluent in Chinese.57 He was dubbed “the oyster” by his fellow foreign residents and was notoriously scathing of their behaviour in China, but he and Marquand got on well, Kates guiding the author on Chinese antiquities and taking him on a mountain trek when Priest’s group made a visit to remote Wutaishan in Shanxi province, south-west of Beijing.58 Kates and the journey may have provided Marquand with much inspiration for Ming Yellow.

Fig.10: George N. Kates (1895-1990), photograph reproduced on the back cover of The Years That Were Fat, c.1950.

Set in warlord-controlled northern China, the story tells of American financier and collector Edward Newall’s quest to acquire a collection of rare Xuande period (r.1426-35) enamel yellow porcelain (the Ming Yellow of the title). The story rehearses the competition between collectors at this time (in this case a fellow American called Rose, whom Newall “is out here to lick”), Chinese dealers in New York (typified by dealer C.T. Loo) and the market for antiques in Beijing.59 Newspaperman Rodney Jones (the hero of the story), living in a courtyard house in Beijing, takes Newall to a dealer in the city, Mr Wong, who reportedly has a piece of Xuande yellow porcelain, but this turns out to be overpainted: “It was a fine rich yellow, which grew to a deeper tone where the flow thickened perfectly at the base”, but the collector was not fooled: “‘The marks are excellent, Jones’, he said. ‘It was a genuine white Ming bowl six months ago. It’s clever faking, but it isn’t worth a dime’”60 Jones reluctantly agrees to take Newall, his daughter Mel and her fiancé, on a journey to the interior of north China where American-educated Chinese, Philip Liu, claims there is a collection in the hands of his uncle, warlord General Wu. Although it is an adventure story of foreigners set against the turbulent backdrop that was northern China during the 1930s, much in the manner of Ann Bridge’s (1889-1974) novels set in Beijing, Marquand demonstrates a knowledge that was current amongst real-life collectors, not least the rarity of Xuande yellow porcelain and the problem that the enamelled yellow could be a later application.61 In the story it is Jones who is presented as the connoisseur, both when he derides the tastes of an earlier generation and when he responds to Newall’s own appraisal of the pieces of genuine Xuande yellow they eventually view:

Our writers and connoisseurs keep harping on the later K’ang Hsi [Kangxi] age as the climax of the potter’s art...Have you ever seen the Ming reds? Your eyes get lost in the depth, and the mellowness of the colour...Once you’ve seen it, I’ll bet you’ll agree no other red can touch it – particularly in the Süen-tê [Xuande] reign around 1530.62

There was hardly any need to look. The mellow flawlessness, the translucent depth of that glaze would probably never be equalled in the world again. If it were, it would take time to give it that mellowness because it seemed to have absorbed the sun’s rays for five hundred years.63

It is hard not to compare Rodney Jones with the character of George Kates whom Marquand befriended and this would not be a unique comparison. Kates has been identified as the character of Philip Flower in Harold Acton’s (1904-94), semi-autobiographical novel Peonies and Ponies.64 Furthermore, Ming Yellow was not the only story by Marquand to feature a Kates-like figure and expatriate collectors in pursuit of Chinese art. Thank You, Mr Moto, serialised and published as a novel in 1936, includes the character of Tom Nelson, a former lawyer immersed in the culture of Beijing and Eleanor Joyce, tasked with collecting a set of Song dynasty paintings for an American museum.65 In both novels Marquand not only draws inspiration from some of those he encountered, but also points to a political situation that allowed collectors, curators, dealers and their agents to freewheel through China in a spate of collecting that only a world war would bring to an end.

In this paper I have discussed some familiar and some obscure collectors of Chinese art, real and imaginary. The actual and fictional come together in an attempt to point up the visibility of artefacts from China that during the period from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century became somewhat familiar in the public mind. This period which lasted into the late 1930s was both one of a growth in knowledge and of opportunity with the familiar blue-and white porcelain of the nineteenth century giving way to the unfamiliar: objects in a huge range of forms and materials and dating from as far back as China’s earliest civilisation. The two went hand in hand. Knowledge of what was collected by individuals and museums grew out of the increased availability of material that was flooding out of China and on to the international art market. Its visibility was the result of major exhibitions such as that mounted in London in 1935-36 and the prominence of collectors whose flamboyance and eccentricity also gave rise to characters in fiction from whom their habits, personalities and situations were drawn. What they all have in common is what Holmes refers to in the “Adventure of the Illustrious Client” as “the collection mania in its most acute form”.66

Nick Pearce holds the Richmond Chair of Fine Arts at the University of Glasgow.

1 The fall of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), was followed by a weak nationalist government, civil war and war with Japan.

2 Lamb took on a persona, Elia and in the essay talks with Elia’s cousin, Bridget, when they are at tea. For a detailed examination of Old China, see Joseph E. Riehl, Charles Lamb’s ‘Old China’, Hogarth and Perspective Painting, in South Central Review, 10/1 (1993), 38-48.

3 Old China was first published by Edward Moxon in the Last Essays of Elia, in 1833. The quotations are taken from Rosalind Vallance and John Hampden, eds., Charles Lamb: Essays (London: Folio Society, 1963), 169-74, 169.

4 Vallance and Hampden, Charles Lamb: Essays, 170.

5 Ibid.

6 Riehl, Charles Lamb’s ‘Old China’, 41.

7 Stacey Pierson, Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560-1960 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2007), 62; see also Clive Wainwright, Murray Marks. ‘A gatherer and disposer of other men’s stuffe’. Murray Marks, connoisseur and curiosity dealer, in Journal of the History of Collections 14/1 (2002), 166.

8 Gerald Reitlinger, The Economics of Taste, 3 Vols. (London: Barrie and Rockliffe, 1963), vol.2, 202.

9 Reitlinger, The Economics of Taste, 202. The market for this material and its collectors is also documented early on by G.C. Williamson, Murray Marks and His Friends (London: John Lane, 1919).

10 What follows is taken from Stephen Coppel, George Salting (1835-1909), in Anthony Griffiths, ed., Landmarks in Print Collecting, Connoisseurs and Donors at the British Museum since 1753 (London: British Museum Press, 1996), 189-203.

11 For a detailed examination of Salting’s Chinese collection, see Konstanze A Knittler, Motivations and Patterns of Collecting: George Salting, William G. Gulland and William Lever as Collectors of Chinese Porcelain, unpublished PhD thesis (University of Glasgow, 2011), Chapter 3.

12 Lindo S. Myers, The Salting Collection of Oriental Porcelain, in The Magazine of Art, London, Paris and Melbourne (1891), 31-36.

13 See The Times, 14 December 1909, Obituary George Salting, 10.

14 Articles appeared in quick succession in The Times on 15 and 17 December, 1909. The bequest was announced in The Times on 23 December and reports continued well into 1910.

15 Salting and Fry were members of the Burlington Fine Arts Club at the same time, Fry joining in 1902, and in 1903, both were instrumental in establishing the National Art Collections Fund, designed to slow the export of paintings from Britain. Stacey Pierson, Private Collecting, Exhibitions, and the Shaping of Art History in London: The Burlington Fine Arts Club (New York: Routledge, 2017), 37 and 53.

16 For details on Fitzhenry see http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/research-journal/issue-02/tea-parties-at-the-museum/ (accessed 17/01.20).

17 Vita Sackville-West, All Passion Spent, first published by The Hogarth Press in 1931. This edition: London: Virago Press, 1983.

18 Sackville-West, All Passion, 39.

19 Ibid., 40.

20 Ibid., 40.

21 Ibid., 199.

22 Ibid., 244.

23 The brief overview which follows of Eumorfopoulos’ life as a collector is taken from Judith Green, Britain’s Chinese Collections: Private Collecting and the Invention of Chinese Art, 1842-1943, unpublished PhD thesis (University of Sussex, 2003), Chapter 5.

24 The entire Eumorfopoulos collection of paintings, frescoes, ceramics, bronzes, jades and sculptures was published by Ernest Benn between 1925 and 1932, authored by R.L. Hobson, W. Perceval Yetts and Laurence Binyon in 11 volumes.

25 Bernard Rackham, Ceramics, a chapter in Chinese Art: An Introductory Handbook to Painting, Sculpture, Ceramics, Textiles, Bronzes and Minor Arts (London: B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1935), 28. Rackham was Assistant Keeper, then Keeper of the Department of Ceramics at the V&A.

26 For details see Green, Britain’s Chinese collections, 161-62 and the same author’s A New Orientation of Ideas: Collecting and Taste for Early Chinese Ceramics in England 1921-1936, in Stacey Pierson, ed., Collecting Chinese Art: Interpretation and Display (London: Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, 2000), 43-56, 51-53.

27 Pierson, Collectors, 115 and 158-59.

28 For a history of the OCS see Frances Wood, Towards a New History of the Oriental Ceramic Society: Narrative and Chronology, in Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 76 (2011-2012), 95-116.

29 Wood, Towards a New History, 96.

30 Brief histories of the Exhibition are provided by Pierson, Collecting, 154-65 and Jason Steuber, The Exhibition of Chinese Art at Burlington House, London, 1935-36, in Burlington Magazine, 148 (August, 2006), 528-36. Eumorfopoulos, Hobson, Rackham and Raphael, were all members of the Executive Committee, under the directorship of another major collector, Sir Percival David (1892-1964). By 1935, the OCS had widened its membership and a number of its members were on the British General Committee of the Exhibition. For a complete list of Committee members, lenders and object list, see the Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935-1936 (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1935).

31 For a discussion of the competing nationalist and internationalist agendas, see Steuber, The Exhibition of Chinese Art, and Ilaria Scaglia, The Aesthetics of Internationalism: Culture and Politics on Display at the 1935-1936 International Exhibition of Chinese Art, in Journal of World History, 26, 1 (2016), 105-137.

32 Steuber, The Exhibition of Chinese Art, 528.

33 As well as the official catalogue, there were a number of spin-off publications which appeared in 1935, two of which were for popular consumption: Chinese Art: An Introductory Handbook (see note 25) and a pocket-size volume, Chinese Art, edited by Leigh Ashton (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1935). Common to all these publications were Laurence Binyon, Bernard Rackham and R.L. Hobson, all of whom were on the Exhibition’s Executive Committee.

34 For details see Steuber, The Exhibition of Chinese Art, 530-31. Each of these exhibitions had major catalogues.

35 Wood, Towards a New History, 99. That year its membership increased from 15 to 120. Year on year it increased it membership.

36 Anthony Powell, The Afternoon Men (London: Duckworth, 1931), 118.

37 A revealing, if colourful, account of King’s social circle was published by his wife: Viva King, The Weeping and the Laughter, An Autobiography (London: Macdonald and Jane’s, 1976). Viva herself was dubbed “the Queen of Bohemia” by Osbert Sitwell and the couple boasted a friendship circle that included Augustus John, Cecil Beaton, Rebecca West and composer and occultist, Philip Heseltine (Peter Warlock).

38 W.W. Winkworth, Obituary, William Augustus Henry King, in Burlington Magazine, 100/663 (June, 1958), 217-18, 218.

39 King, The Weeping, 139.

40 Angus Wilson, Old Men at the Zoo (London: Secker & Warburg, 1961). For the reference to King see C.J. Wright, Willie King: One of Angus Wilson’s Old Men at the Zoo http://www.bl.uk/eblj/2017articles/pdf/ebljarticle82017.pdf (accessed 28/01/2020).

41 King, The Weeping, 167.

42 Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Illustrious Client, was first published in The Strand Magazine in February-March, 1925 and then in The Case-Book of Sherlock Holmes, by John Murray in 1927. The edition used here was published by Penguin Books in 1951, 9-37.

43 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 14.

44 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 14.

45 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 12.

46 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 29.

47 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 28.

48 R.L. Hobson, Chinese Pottery and Porcelain, 2 volumes (London: Cassell & Co., 1915); The Wares of the Ming Dynasty (London: Ernest Benn, 1923). The 1920s and 30s witnessed a re-positioning of Ming ceramics in the minds of collectors who were moving from an appreciation of brilliant seventeenth and eighteenth-century porcelains to much earlier wares. It gave rise to the association of the Ming vase with preciousness, rarity and, as referenced in Conan Doyle’s story, the imperial court. See Stacey Pierson, From Object to Concept: Global Consumption and the Transformation of Ming Porcelain (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013), 57-80 and 90-96.

49 Ernest Grandidier, Le Céramique Chinoise (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1894).

50 E.C.C. Baly, Obituary, Prof. J.N. Collie FRS, in Nature, 150 (1942), 655-56; Alwyn G. Davies, J. Norman Collie, the Inventive Chemist, in Science Progress (2014), 97/1, 62-71.

51 The comparison of Collie with Holmes is discussed in Davies, J. Norman Collie, 64.

52 After his death most of Collie’s collection was sold and dispersed. See Sotheby & Co., Catalogue of the well-known Collection of Chinese Ceramics, Bronzes, Jades and Works of Art. The Property of Prof. J. Norman Collie, FRS, deceased, sold by order of the Executors, 8-9 April, 1943.

53 Collie’s cousin was Stephen D. Winkworth, noted previously, who was another co-founder of the OCS. Stephen’s father (also named Stephen), was a member of the Alpine Club and probably introduced the young Collie to climbing. For details of this and the family relationship, see Christine Mill, Norman Collie, A Life in two worlds. Mountain explorer and scientist, 1854-1942 (Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press, 1987). Collie loaned two objects to the exhibition, items 2768 and 2862, a white jade vase and a pale green jade brush pot, Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935-6, items 238 and 245.

54 Millicent Bell, Marquand: An American Life (Boston: Little Brown, 1979).

55 Bell, Marquand, 204-5.

56 Ming Yellow appeared in six parts from December, 1934 to mid-January, 1935, with the novel appearing later the same year. The Mr Moto novels were intended to continue the success of the Charlie Chan stories, the author of which, Earl Derr Biggers, had died the year before. As with Charlie Chan, Mr Moto became a popular film character with Peter Lorre playing Moto.

57 Bell, Marquand, 216-17. Kates’ account of his life in Beijing can be found in The Years That Were Fat (Harper & Brothers, 1952). His Spartan life is described on pages 21-22, with his censorious views clearly stated on pages 80-81. For a life of Kates, see John Roote, A Love Affair with Old Beijing: The Remarkable Story of George Kates (Kindle Edition, Forbidden City Books, 2015). For an insight into the life and behaviour of the “foreign community” in Beijing of the 1930s, see Julia Boyd, A Dance with the Dragon: The Vanished World of Peking’s Foreign Colony (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2012).

58 Bell, Marquand, 216-17 and 501.

59 John P. Marquand, Ming Yellow (London: Lovat Dickson &Thompson Ltd, 1935), 29-35.

60 Marquand, Ming Yellow, 42-43.

61 Ann Bridge (Mary Dolling Saunders O’Malley), Peking Picnic (1932) and The Ginger Griffin (1934)

62 Marquand, Ming Yellow, 127.

63 Marquand, Ming Yellow, 242.

64 Harold Acton, Peonies and Ponies (London: Chatto & Windus, 1941). An aesthete as well as writer, Acton lived in Beijing between 1932 and 1939 and was a friend of Kates. He was also a member of William and Viva King’s social circle.

65 Richard Wires, John P. Marquand and Mr Moto, Spy Adventures and Detective Films (Muncie, Indiana: Ball State University, 1990). 15-36.

66 Conan Doyle, The Adventure, 29-30.