ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Project Report

by Nathalie Neumann / Adam Ganz

The Reconstruction of the Art Collection of Felix Ganz (1869-1944)

Felix Ganz was a businessman from Mainz in southwest Germany. He was managing director of Ludwig Ganz AG, a carpet and textile company. Felix Ganz was also an art collector with a substantial collection of art objects from the Middle East and East Asia. As soon as the National Socialists came to power, Ganz (though baptised a Protestant) was persecuted as Jew. In 1934, his company was “aryanized”, in 1941 his home was seized and in 1942 Ganz and his second wife Erna (née Benfey) were deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp. In 1944, the couple was murdered in Auschwitz.

Even though his three children survived, the art collection had disappeared, and only a rough description of the items from restitution claims remains. The aim of the project presented in this article is it to reconstruct the scope and character of Felix Ganz’ art collection and to research the mechanisms of its dispersion between 1933 and 1945 as well as the location of the objects today. The article was co-authored by the great-grandson of Felix Ganz and a French-German art historian specialising in provenance research.

Felix Ganz (1869-1944) was a businessman from Mainz in southwest Germany. He was managing director of Ludwig Ganz AG, a company that successfully dealt in oriental carpets and textile products for furniture and home décor. Felix Ganz was also an art collector with a substantial collection of art objects from the Middle East and East Asia. As soon as the Nazis came to power, Ganz (though baptised a Protestant) was persecuted as Jew. In 1934, his company was “aryanized”, in 1941 his home was seized and in 1942 Ganz and his second wife Erna (née Benfey) were deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp. In 1944, the couple was murdered in Auschwitz.

Even though his three children survived, the art collection had disappeared and only a rough description of the items from restitution claims remains: “Felix Ganz owned an important art collection with art and decorative art objects from ‘Near and Far East’ which he had collected during his frequent business trips to Paris and London, but also to Istanbul, Greece and Egypt.”

Fig. 1: Felix Ganz (left) with his family in his home on the Michelsberg around 1914: his daughter Olga, his wife Gertrud, his second daughter Anne-Marie and his son Hermann.

Family archives © Ganz Family

The Authors and their Methodology

The two authors of this article chose to combine their research and methods. Adam Ganz, great-grandson of Felix Ganz based in London, had begun to research the fate of his great-grandfather, of his company Ludwig Ganz AG, and of his private art collection. He had access to a small amount of family correspondence and of course information on family, friends and business partners. Nathalie Neumann is a French-German art historian specialising in provenance research. Following a meeting in November 2018 at the Berlin workshop Provenance Research on East Asian Art #2, their research proposal to investigate the fate of his collection over a period of twelve months was accepted for funding by the German Lost Art Foundation (Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutveluste) in October 2019. The project is directed by Professor Elisabeth Oy-Marra at the art history department at Mainz University and started in spring 2020.1

The authors adopt a dual approach to reconstruct the art collection, combining methods of provenance research with the microhistorical account of an assimilated Jewish family in a regional German town. The results will be communicated in further conferences and an exhibition.

Initial research on the historical context of the fate of Felix Ganz and the looted objects has been conducted by Adam Ganz, Dr Bettina Leder, and a group of researchers from the Fritz Bauer Institut mainly linked to the fate of Felix Ganz family and the seizure of their possession.2 In 2016, the Landesmuseum Mainz tasked the provenance researcher Emily Loeffler with checking the provenance of a group of fine and decorative art objects. Among them she identified three items formerly belonging to Felix Ganz which had been seized.3 The authors’ research is based on these initial results. During the project they will develop new methods in reconstructing the art collection of Felix Ganz specifically and the historic context of collecting and National Socialist confiscations of cultural assets in general. No documents on the art collection prior to its seizure are known so far. The collection seems to have disappeared almost without trace. The aim of the project is to develop a set of methods for the reconstruction of the scope and character of Felix Ganz’ art collection and for research on its dispersion between 1933 and 1945, as well as on todays location of the objects.

Felix Ganz was the tenth of eleven children of Ludwig Ganz, a businessman in Mainz. In 1890 Felix took over the family business which dealt in oriental carpets and textile products for furniture and home decoration. In 1906 he expanded the shop at Schillerplatz in Mainz, and in 1913 he transformed the firm into a joint-stock company. During World War I, even though Felix was already forty-five years of age and thus near the age limit when World War I broke out, both he and his son Hermann saw action on the front line. Whilst Felix was on active service, his first wife Gertrud (née Wieruszowski) who had been born in Görlitz in 1871, took over the management of the business. After the war, Felix grew the business further. In 1920, he built new headquarters in Bingerstrasse 26 in Mainz, designed by the architect Phillip Schaefer.4

Business associates of the firm Ludwig Ganz AG included successful businessmen such as Rudolph Karstadt (1856-1944), founder of the Karstadt department store chain, and the finance expert Dr Hjalmar Schacht (1877-1970), later Finance minister and President of the Reichsbank. The company maintained a wide network of production facilities in the Middle East and Germany and had several German branch offices in Mainz, Wiesbaden and Berlin as well as associates in Paris and Strasburg and in the United Kingdom. In addition, Ludwig Ganz maintained offices in Constantinople (Istanbul), Tiflis (Tbilisi) and Smyrna (Izmir).

In 1920, Felix Ganz moved into a large villa on the Michelsberg overlooking the Rhine. He also built a house for his son Dr Hermann Ganz (Company Secretary of Ludwig Ganz AG) who had just founded a new family with his wife Dr Charlotte Ganz (née Fromberg), from a Frankfurt banking family. Felix Ganz played a substantial role in the cultural life of the city of Mainz. In 1921 he was elected Schriftführer (secretary) of the Gutenberg Society with headquarters in Mainz, and he was a member of the local cultural societies Mainzer Liedertafel and Mainzer Altertumsverein, as well as a financial supporter of the antiquities museum, the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum.

His younger daughter Olga was a soprano who appeared on Radio Luxemburg and was friends with conductor Hermann Scherchen (1891-1966). His older daughter Annemarie was the writer Carl Zuckmayer’s first wife. Zuckmayer described his father-in-law as a man of great intelligence with thorough knowledge of oriental art.5

In 1934 the firm Ludwig Ganz AG was “aryanized” and the shop was taken over by Julius Ochsenreither, the former general manager (Prokurist). Felix’ son Hermann Ganz went to work as a salesman for Rheinische Textilfabriken in Wuppertal. In October 1938 Hermann was offered employment by Morton Sundour, a Scottish textile company, as European sales manager – he had excellent business contacts throughout Europe and spoke several languages including Turkish. Hermann started working for Morton Sundour in November 1938. In his new capacity he visited contacts in Germany and tried to get visas for his wife and children to go to the United Kingdom. He was in Mainz on the night of the 9 November pogrom, as were Hermann’s wife and younger son Ludwig called Lutz, who later took the name Lewis H Gann as historian.6 In Mainz the Ganz family appear to have had some protection, as neither Felix nor Hermann were arrested and the collection seems to have remained untouched. However Hermann’s son Peter,7 who was in Frankfurt, was imprisoned and deported to Buchenwald concentration camp in November 1938. Due to the efforts of the Morton family who were cognisant of the dangers, Peter and his brother were able to come to England.8 Hermann’s wife Charlotte joined them in 1939. Annemarie fled to Lausanne, and Olga arrived in London in May 1939. Felix attempted to escape but ultimately he and his second wife Erna, who he had married after Gertrud died in 1936, were forced to stay in Mainz as their visas did not come through. At one stage he tried to sell some furniture to the Morton family.9 There is also evidence that he was selling carpets from his house.10 The couple continued to have some special privileges, as they were for example allowed to stay in the Michelsberg house until 1941. They then moved several times and ended up in a “Jew House” in Kaiserstrasse 32. In 1942 they were deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp and murdered in Auschwitz two years later.

Three objects that Felix Ganz had taken to Kaiserstrasse were the abovementioned discoveries in the Landesmuseum in Mainz,11 but there is no trace of his art collection in general, nor his personal library or the stock of the carpet warehouse so far.

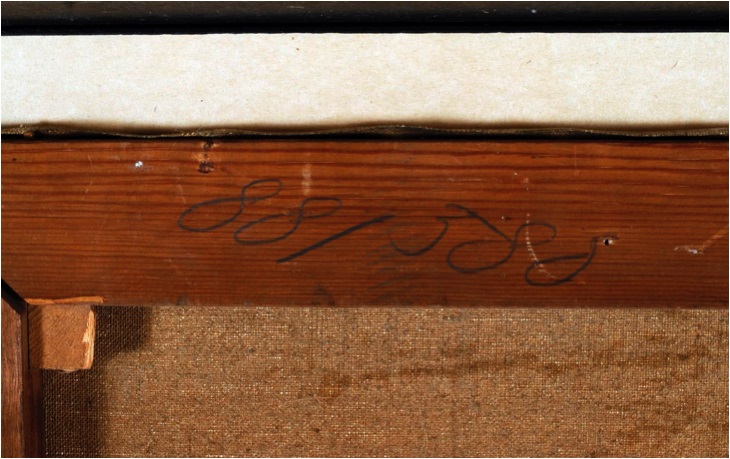

The research is defined by a time window, beginning with January 1933, the start date of persecution, with particular focus on the year 1941 when Felix Ganz and his wife Erna had to leave their home, the villa on Michelsberg 6-8, taking just a small amount of objects with them to several temporary locations until settling in the “Jew House” in Mainz at Kaiserstrasse 32 where they shared a single room with Erna’s mother Marie Benfey (1874 – 1943). In his post-war witness report the lawyer Michel Oppenheim (1885-1963) mentioned that Felix Ganz kept a number of boxes containing objects from his art collection there.12 Most of these personal belongings were later circulated through the local Finance ministry and sold at auction. A few were given to the Landesmuseum Mainz in 1941. During her abovementioned research for the museum Emily Loeffler was able to match the marks on the items to the identifying numbers allocated by the Finance ministry to mark property from a variety of families from Mainz. She was able to trace when, how and which objects were seized, naming prior owners and actors of the confiscation process. Three objects matching the individual mark for Felix Ganz of the Finance Ministry were thus identified by the code M. St. 88/580 which was marked on the seized items now at the Landesmuseum. A second mark can also be identified on the “Sollkarte” (debit index card) in the archives of the Finance department, a type of tax and income file held on individuals at the ministry: Landeszentralbank, Devisenstelle Frankfurt/Main 263/33. Items formerly in the possession of Felix Ganz’ mother-in-law Marie Benfey were marked M. St. 88/521.13

Fig 2: Frame of painting (verso): Conrad Sutter (1856-1927), Landschaft mit Heuernte (Lichtenberg) View of Lichtenberg, oil on canvas, 71 x 95 cm. GDKE, Direktion Landesmuseum Mainz, Inv.-Nr. 1220 – showing finance identity mark for Felix Ganz: M. St. 88/580

© GDKE - Landesmuseum Mainz (Ursula Rudischer)

These identification marks form the basis for research in other German museum collections to identify further art works of “Near or Far Eastern” art objects with unknown provenance which may have belonged to the Ganz family.

The time window of the project ends in 1949-1956 with the compensation and restitution claim after World War II, when Felix Ganz’ three surviving children Hermann Ganz (1896 - 1957), Annemarie (Zuckmayer/Lips) Kaulla (1898–1984) and Olga (Kreiß) Rickards (1900–1974) tried to recover items from the family business and receive compensation for the devastation of their home and private property.14

Objects

The claim of Felix Ganz’ daughter Annemarie Kaulla is the only document providing details of the art collection and therefore an important source for its reconstruction.15 Even if the description is vague it gives an idea of the quality and volume of the collection, including the holdings of objects from East Asia:

Fig. 3: Wooden sculpture of Virgin Mary with child, from the workshop Syrlin or Erhart around 1510. Only photograph of art work from the art collection Felix Ganz. Cf. Lostart.de object ID 590487.

family archives © Ganz Family

“There were handicrafts of every possible kind of craftsmanship: carpets, weaving patterns, brocade, embroidery, cloths of Asian and East Asian origin, Coptic works, Persian miniatures, Japanese woodblock prints, lacquer work, ivory carvings, wood carvings, paintings on silk, ink paintings, Japanese scroll paintings, scrolls, Tibetan old manuscripts, pottery of Persian origin (14th century), Spanish faience (17th century), antiquities from the Greek islands, Chinese grave sculpture (Tang, 9th century) to Ming (17th century), metalwork, Persian inlay work, Chinese Bronzes, cloisonné (mine melting), Japanese sword guards (Tsuba), jade and rock crystal work, Chinese porcelain....”.16

This description from Annemarie’s restitution claim serves as the starting point for the object-oriented research and reconstruction of the Felix Ganz collection. Reconstruction involves tracing the history of the collection by identifying where, when and what Felix Ganz bought. This implies knowing his taste, his travels, his art literature and his exchanges with the art world and art experts. Some details are mentioned by Annemarie Kaulla, others by post-war witnesses who knew the art collection of her father, such as museum curators from Berlin.

Amongst the experts Felix Ganz contacted were the director of the Islamic art collection in Berlin, Friedrich Sarre (1865-1945), his assistant and successor, the archaeologist and expert on oriental art Ernst Kühnel (1882-1974) and his wife, the art historian Irene Kühnel-Kunze (1899-1988). At this point, we found not only evidence that he contacted the museum staff for expertise on a carpet but also in the context of his donation of a Japanese painting to the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (East Asian Art Museum) in Berlin in 1932.17

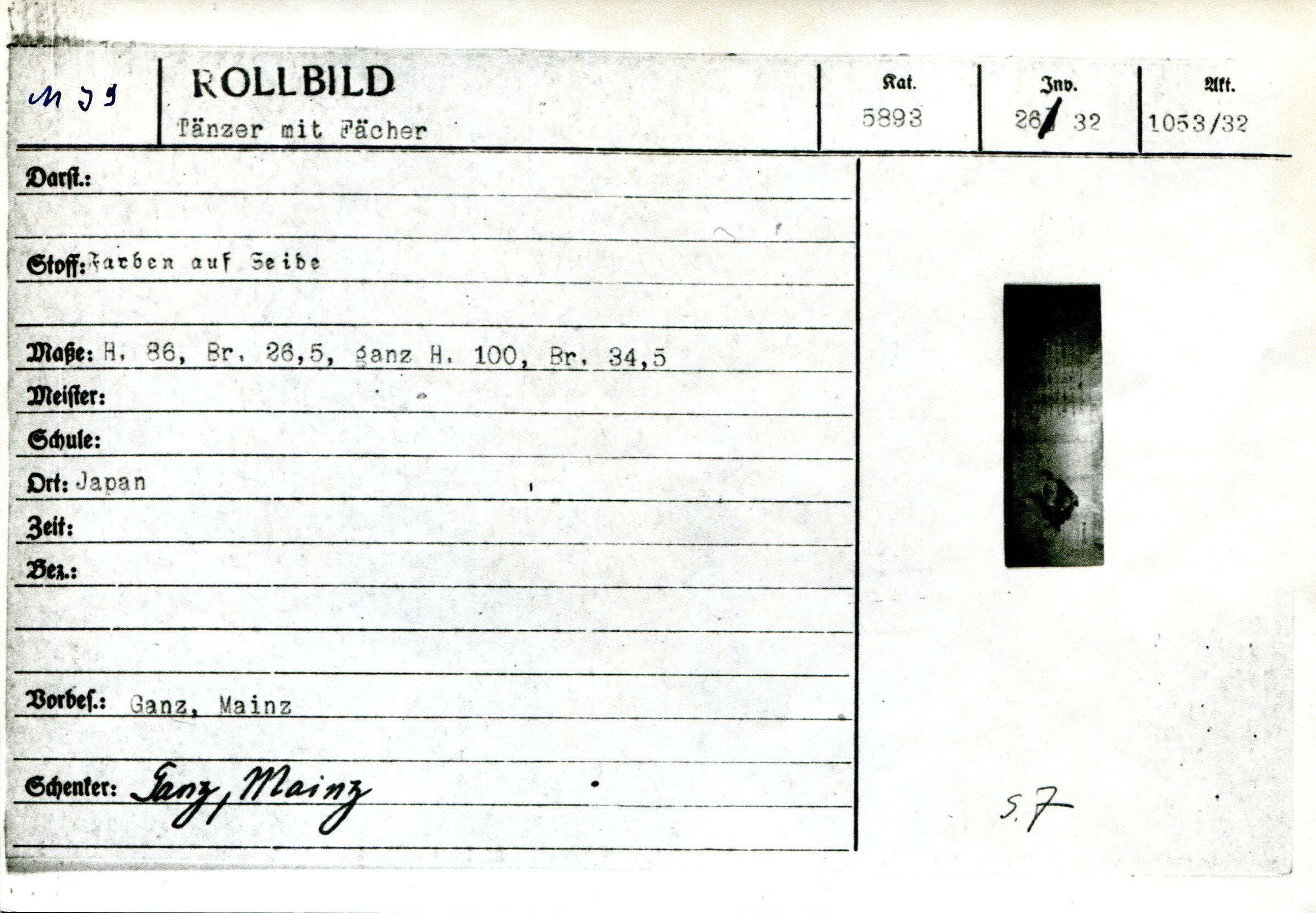

As a donated object separate from the seized collection, it helps us to better understand Felix Ganz’s exchange of objects with experts. He made the donation to the East Asian Art Museum in Berlin, directed by Otto Kümmel (1874-1952), in October 1932.18 The scroll in question was painted by the Japanese artist Kawanabe Kyosai (1831-1889) and probably represented a kabuki actor or dancer.19 According to the current curator of the collection, Dr Alexander Hofmann, it was the first and, for several years, only work by this important artist in the Berlin East Asian Art collection. Otto Kümmel himself writes on 7 October 1932 to Felix Ganz: “Warmest thanks for the donation of the beautiful Japanese scroll. The picture bears a first inscription dated 1837 and a second with the reference to Gyosai [sic].”20 Unfortunately the work itself is no longer in the collection of the museum. It was either destroyed during World War II or belongs to the group taken by the Russian Allies to Russia as so-called trophies after 1945. Its only trace today is the museum’s inventory book and the copy of the index card with a very poor photograph.

Yet the provenance of this scroll before it entered the Felix Ganz collection may help to find the place, the auction, the collector or expert where Felix Ganz bought the item. Supposing that he bought repeatedly from the same source, it may be possible to trace other purchases by him. We may also gain some insight into what prompted him to make that donation at that time.

Felix Ganz was not only a collector but also a successful carpet dealer with an active social and cultural life. It is therefore useful to try and analyse the social contacts Felix Ganz may have maintained with personalities from industry and business, whose personal archives and private correspondence may provide information on the art acquisitions of Felix Ganz. Such personalites are Dr Hjalmar Schacht (1877-1970), later Reichsbank President and Reich Finance Minister, Dr. Heinz Nordhoff (1899-1968), tenant of the Ganz family in the late thirties while working for Opel in Rüsselsheim, who became managing director of Volkswagen in 1948, and John Berenberg, an interior designer in Würzburg mentioned as a contact in Felix Ganz’ last letter before his deportation. Family archives such as the correspondence found with Felix’ brother Theodor Ganz, his niece Annemarie Ganz, later Annemarie Brenzinger, and her husband Heinrich Brenzinger (1879-1960) who was also a close friend of Felix have proved crucial for the authors’ research. This correspondence covers almost four decades and describes some of the early business relationships between the two families. Brenzinger and Felix Ganz went together to art galleries in the 1910s and discussed joint business ventures. Unfortunately, their correspondence in the thirties and forties diminishes and becomes increasingly elliptical; as Heinrich Brenzinger needed to protect himself, his Jewish wife and his business from persecution. The correspondence is currently being sorted and analysed by the historian Sandra Lipner and gives an extraordinarily detailed picture of family and business life. Apart from the case of a Renaissance sculpture, correspondence about the art collection has not been discovered so far. This suggests that most of the collection was of specific, rather than general interest.21

Fig. 4: Copy of inventory Card for Felix Ganz donation to the Museum of East-Asian Art Berlin in October 1932: Hanging scroll signed Kyosai, dated 1873.. Kat. (i.e. catalogue) 5893, inv. (i.e. inventory no. 28 / 32 and Akt. (i.e. Akten or document no.) 1053/32.

Archive of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin © SMB Berlin

The private home and business offices, friends’ houses and family places will be further topics of research, such as the villa on the Michelsberg under French occupation (Saarland and Rhineland 1923-1930), and the social events held there whose descriptions may be reflected in correspondence and press. Knowledge of trade offices in Wiesbaden and Berlin, but also abroad in London, Paris, Izmir, Istanbul, Tbilisi and Tabris (all cities where the Ludwig Ganz AG was active) may help to shed light on Felix Ganz’s interactions with art experts, dealers and antiquarians. The archive of international trade of the respective countries, their embassies as well as the archive of the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Politisches Archiv) are being contacted to trace Felix’ travels in today’s Turkey, Georgia, and Iran, while searching for his travel and business correspondence, import and export files. The historical international press is checked for promotions, advertisements, administrative procedure information and so forth to trace Felix Ganz’ activities. In Mainz itself, a long financial process covering almost ten years, preserved the business correspondence of the company Ludwig Ganz AG with the Chamber of Commerce in Berlin was transferred in 1928 to Mainz and is preserved at the Landesgericht Mainz.22 The business reports over almost twenty years give the names of lawyers and explain strategies but also relationships in the dealings with the company, stock owners and market activities.

The authors’ attempts to reconstruct the private art collection of Felix Ganz also has added significance in restoring the history of a Mainz family which once played a considerable role in the cultural life of the city and whose existence the Nazis attempted to erase, in every sense. Whether or not objects can be located and restitution processes engaged, the work will have been worthwhile in helping to connect the descendants of Felix Ganz to their roots in Mainz and vice versa.

Nathalie Neumann is a Senior Provenance Researcher at the IKM University of Mainz. Adam Ganz is the great-grandson of Felix Ganz.

Altchinesische Fayencen

etwa 8 figürliche Darstellungen, Ton, ohne Glasur, Spuren von Farbe, Grabbeigaben aus der Epoche Tang, ca. 9. Jhdt., Pferd, Reiter, weibliche Figuren

Altpersische, spanische, syrische Fayencen:

7-9 persische Schalen, sog. Rhages, 14. Jhdt., blau und türkis, selten gute Exemplare, spanische Fayence-schüsseln mit braungoldenem Dekor (5 Stück), 3 syrische antike Gläser. (keine Copien – nur Originale)

2 (?) fünfteilige, große chinesische Wandschirme:

Schlachtendarstellungen auf Goldgrund, etwa 17. Jhdt., offensichtlich historische Gemälde. Herkunft schwer lokalisierbar. Diese Wandschirme waren wegen ihrer starken Farbigkeit, ihrer (?) und wohl auch wegen ihres Wertes wegen in einem besonderen Schrank aufgehoben. 2/5

Japanischer Tempel: ca. 1.30m hoch, ausgezeichnet erhalten reich dekorierte Nachahmung eines größeren Heiligtums, geschnitztes Holz mit Goldlack- und Bronzeverzierungen.

Persische Kaminverkleidung: bestehend aus weißgrundigen persischen Ispahan-Kacheln, Dekor farbige Pflanzenornamente, deren Zeichnung ein Ganzes ergab. Ca. 17.Jhdt.

Tibetanisches Seidenbild

Grosser Buddha auf Thron

5 chinesische Tusch-Rollbilder

schwarz, jede Rolle ca. 1,20m lang, in alter Brokatfassung, weitere chinesische Bildrollen (3 oder 4 Stück), jede einige Meter lang, mit handgemalten Märchendarstellungen, 18. Jhdt. Spätere gestickte Seidenbilder.

Japanische Farbholzschnitte, 18. (?)Jhdt.

Eingebaute, persische Wandtäfelung

ca. 1m lang, 1.50 hoch, aus Rosenholz, feinste durchbrochene Schnitztechnik, Architekturmotive, einem zarten Gitter gleichend.

eingebaute chinesische Wandfüllungen, etwa 12 Stück, ca. 80/80 holzgeschnitzt, Flachrelief, typische Zeichnung wie etwa auf chinesischen Teppichen: Pflanzen mit geometrischen Dekor.

graviertes Tablett, ca. 80cm Durchmesser, eingelegt mit Gold und Silber, feinste persische figürliche Zeichnung, Reiter, Ritter, Tiere, Pflanzen, als Tisch montiert

Gartenbronzen

2 Störche (oder Reiher ?), Höhe etwa 1.20, japanisch, großer Tempel, etwa 1.50 hoch, stark verziert, typisch chinesische Formen, ebenso Laterne

Stickereien

aus dem ganzen Orient ausgesuchten Stücke von Textilkunst, jeder vorstellbaren Nadeltechnik, auch Spitzen,

Teppiche

sowohl gewirkte wie geknüpfte antike Stücke aus Anatolien, China, Persien, Kaukasien, Tierteppiche, Vasen-, Garten-, Gebetsteppiche u.a., Seidenteppiche mit Goldfäden, alt-chinesische Sattel- Kahabr (?) decken .

Marmorskulpturen

etwa 6 50cm hohe eigenartige halb-figürliche, halb-ornamentale Marmorarbeiten, die auf eigens eingebauten Wandfüllungen mit chinesischen Goldfiguren, auch etwa 6-8, „Heilige“ darstellend.

Ancient Chinese faience: approximately 8 figures in clay without glaze, traces of colours, burial objects from the Tang period, ca.9th ct., horse and horse man, female figures

Ancient Persian, Spanish and Syrian faience: 7-9 Persian bowls, so called Rhages, 14th ct. blue, seldom (rare?) valuable pieces

Spanish faience-bowl with brown gold glaze (5 pieces), 3 Syrian ancient glasses

2 large Chinese folding screens (5 parts panels? each): showing battle scenes on golden background approx. 17th c., historical topic, provenance unknown. These screens were stored in a special cabinet because of their intense colours, and probably also because of their value.

Japanese temple: about 1.30m high, excellently preserved richly decorated, served as an imitation of a larger sanctuary; made out of carved wood with gold lacquer and bronze decorations.

Persian fireplace cladding: consisting of white-ground Persian Isfahan tiles, decor coloured plant ornaments, the drawing of which gave a whole. Approx. 17th century

Tibetan silk picture with a big Buddha seated on throne

5 Chinese ink scrolls black?, each scroll about 1.20m long, in old brocade version,

further Chinese picture scrolls (3 or 4 pieces), each a few meters long, with hand-painted fairy tales, 18th century

Later embroidered silk pictures.

Japanese woodblock prints, 18th (?) Century

Built-in Persian wall panelling approx. 1m long, 1.50 high, made of rosewood, the finest openwork carving technique, architectural motifs, resembling a delicate grid.

built-in Chinese wall fillings, about 12 pieces, about 80/80 wood carved, bas-relief

Typical drawing(S?) such as on Chinese carpets: plants with geometric decor.

engraved tray, approx. 80cm diameter, inlaid with gold and silver,

finest Persian figurative drawing, rider, knight, animals, plants, mounted as a table

Garden bronze 2 storks (or heron?), Height about 1.20, Japanese,

large temple, about 1.50 high, heavily decorated, typical Chinese shapes, as well as lantern

Embroidery and pieces of textile art selected from all over the Orient, any conceivable needle technique, including lace and carpets both knitted and knotted

antique pieces from Anatolia, China, Persia, Caucasia, animal carpets, vase, garden, prayer carpets, etc., silk carpets with gold threads, ancient Chinese saddle-Kahabr (?) blankets.

6-8 marble sculptures about 6,50cm high peculiar semi-figurative, semi-ornamental marble works, depicting “saints” on specially installed wall fillings with Chinese gold figures

1 https://www.kunstgeschichte.uni-mainz.de/files/2020/04/Homepage_IKM_Uni_Mainz_-Felix-Ganz-1.pdf [accessed: 15 April 2020],

2 Susanne Meinl, Jutta Zwilling, Legalisierter Raub: die Ausplünderung der Juden im Nationalsozialismus durch die Reichsfinanzverwaltung in Hessen (Frankfurt/Main [u.a.]: Campus-Verlag, 2004),

3 Emily Löffler, Final Report for the project “Recherche nach Provenienzen und Besitzverhältnissen von widerrechtlich entzogenen Gemälden, Grafiken und Möbeln jüdischen Besitzes“ at the Landesmuseum Mainz funded by the German Lost Art Foundation in Magdeburg (unpublished), 56.; the same: “... eine grössere Anzahl von Kunstgegenständen aus jüdischem Besitz...“ Überweisungen der Reichsverwaltung im Landesmuseum Mainz“, in Evelyn Brockhoff and Franziska Kiermeier, eds., Gesammelt, gehandelt, geraubt Kunst in Frankfurt und der Region 1933 bis 1945 ( Frankfurt am Main: Societäts Verlag, 2019), 196-210.

4 The newspaper Mainzer Anzeiger from 27 October 1920 mentions in a report on the opening ceremony that the company owned a carpet which was worth 2 million marks. The architect went on to design the landmark Karstadt department store building at Hermannplatz in Berlin in 1927.

5 Carl Zuckmayer, Als wär’s ein Stück von mir (Frankfurt a.M.: Fischer, 2013), 223.

6 Gann describes his memories of watching the synagogue burning in: Kristallnacht Reflections, in: American Spectator, vol. 22, no. 1, January 1989.

7 Peter was Adam Ganz’ father. He just had turned eighteen in 1938 and was enrolled in an apprenticeship with a leather firm in Frankfurt after having been forced to leave school because of the Nuremberg Laws.

8 This account is based partly on family correspondence and partly on extensive records in the National Records of Scotland, Papers of the Morton Family of Darvel, GD326/944 and GD326/945/28 ff.

9 “He would not be able to take this with him and you would be free to buy everything you wanted”, source: see above.

10 See Advertisement in: Der Schild, 24 July 1938.

11 The article follows up the research project of the Landesmuseum Mainz, finded by the German Lost Art foundation (DZK) and documented in the report by Dr Emily Löffler (see footnote 3).

12 Amt für Wiedergutmachung Saarburg, Reg. Nr. 177.060 (Entschädigungsakte Felix Ganz). Stadtarchiv Mainz, Nachlass Oppenheim, Archive Oppenheim NL Oppenheim/49,2-4. This deposit is an important resource as Michel Oppenheim acted since 1941 as mediator between the GESTAPO and the Jewish community. He noted his observations secretly in a diary. His notes have been digitized and made available online [https://faust.mainz.de/nzeig.FAU?sid=87078D675&dm=1&erg=A&qpos=31; entry 39-41, accessed: 11 November 2020].

13 See footote 3.

14 Amt für Wiedergutmachung Saarburg, Reg. Nr. 174 909 (Entschädigungsakte Olga Rickards);Amt für Wiedergutmachung Saarburg, Reg. Nr. 177.060 (Entschädigungsakte Felix Ganz); Amt für Wiedergutmachung Saarburg, Reg. Nr. 273 620 (Entschädigungsakte Erna Benfey); Bundesamt für Zentrale Dienste und Offene Vermögensfragen (BADV), OFD-Akte, O 1489 (403.124) (Rückerstattungsakte Felix Ganz).

15 It is likely that objects lists for insurance or for the “Reichfluchtssteuer” (tax on Jews who were forced to emigrate) existed. The authors hope to locate them if they still exist.

16 Bundesamt für Zentrale Dienste und Offene Vermögensfragen (BADV), OFD-Akte, O 1489 (403.124)(Rückerstattungsakte Felix Ganz), summary and translation by the authors, see appendix for detailed list including the approximate estimation of the objects’ value.

17 SMB-ZA, I/IM 065 - Allgemeiner Schriftwechsel der Abteilung, E - H (Ludwig Ganz AG).

18 Otto Kümmel thanks Felix Ganz for his donation. Zentralarchiv SMB I/MfV, OAK 06.

19 Thanks goes to the team of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin: Documents in the museum: Kat. (i.e. catalogue) 5893, inv. (i.e. inventory no.) 28 / 32 and Akt. (i.e. Akten or document no. 1053/32).

20 Translation from German to English by the authors. Zentralarchiv SMB I/MfV, OAK 06_157.

21 Private publication: Andrea Haussmann, Heinrich Brenzinger (1879-1960), ed. Dr. Frank Dyllick-Brenzinger, Freiburg 1996, 74-76. Sandra Lipner, the great-grand-daughter of Heinrich Brenzinger has just begun her doctoral thesis at Royal Holloway, University of London on ”Microhistories of the Holocaust and the Use of Family History: The Families Ganz / Brenzinger, c. 1871 – 1945” under the supervision of Professor Dan Stone. We are very grateful to Sandra Lipner and the Dyllick-Brenzinger family for access and permission to quote from this material.

22 Landesarchiv Speyer: Bestand J44 Amtsgericht Mainz – Sachakte 2106 Handelsregisterakten Continentale Bank- und Handelsaktiengesellschaft, Mainz; J 44 – Sachakten 2219, 2220, 2221 Ludwig Ganz Handelsregister.