ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Noelle Giuffrida

This essay provides a window into the circulation of Chinese paintings during the tumultuous political and economic environment of the 1940s and 1950s by examining Sherman E. Lee’s acquisitions of paintings from Walter Hochstadter during Lee’s early years as curator of Asian art at the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1952-1958. This essay demonstrates that the surge in collecting Chinese paintings in postwar America and efforts to examine the major figures and historical circumstances behind this phenomenon are crucial to expanding our understanding of the history of collecting Chinese art beyond its country of origin. Lee’s acquisitions of paintings from Hochstadter in the 1950s was also facilitated by competing curators’ inability to make purchases, for example German Sinologist and art historian Ernst Aschwin Prinz zur Lippe-Biesterfeld, commonly known as Aschwin Lippe, who became a senior research fellow at the Metropolitan in 1949. Provenance research in this field crucially relies on archival research. The Freer|Sackler Galleries at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., regularly grant researchers access to its many collections of personal papers of important curators such as Aschwin Lippe, James Cahill (1926-2014), and John Alexander Pope (1906-1902). The author consulted Hochstadter’s papers at the Center for Jewish History and the Frank Caro Archive at the Institute of Fine Arts in New York. The author also consulted Sherman Lee’s personal papers preserved by his family.

During the twentieth century, museums in America amassed distinguished collections of Asian art. In the decades following World War II, the United States emerged as an international center for the study and presentation of Chinese art. Political, economic, and social factors around the globe affected the art market, prompting a new wave of collecting Chinese paintings involving curators, dealers, and private collectors living in the United States. American curator and museum director Sherman E. Lee (1918–2008) and German expatriate dealer-collector Walter Höchstädter (1914-2007, aka Hochstadter) stand out as two of the most important figures behind these developments.

This essay provides a window into the circulation of Chinese paintings during the tumultuous political and economic environment of the 1940s and 1950s by examining Lee’s acquisitions of paintings from Hochstadter during Lee’s early years as curator of Asian art at the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1952-1958. An analysis of Lee’s collecting of Chinese paintings within the larger context of an international network of curators, dealers, and collectors reveals how the activities of other figures of the time including New York dealer Frank Caro (1904-80) and Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Ernst Aschwin Prinz zur Lippe-Biesterfeld (1914-88), affected how and why Lee collected particular works for Cleveland from Hochstadter and other sources during the 1950s.

Thus far, the majority of scholarship on the provenance and collecting of Chinese art beyond East Asia has focused on the late nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century. This essay, however, demonstrates that the surge in collecting Chinese paintings in postwar America and efforts to examine the major figures and historical circumstances behind this phenomenon are crucial to expanding our understanding of the history of collecting Chinese art beyond its country of origin.

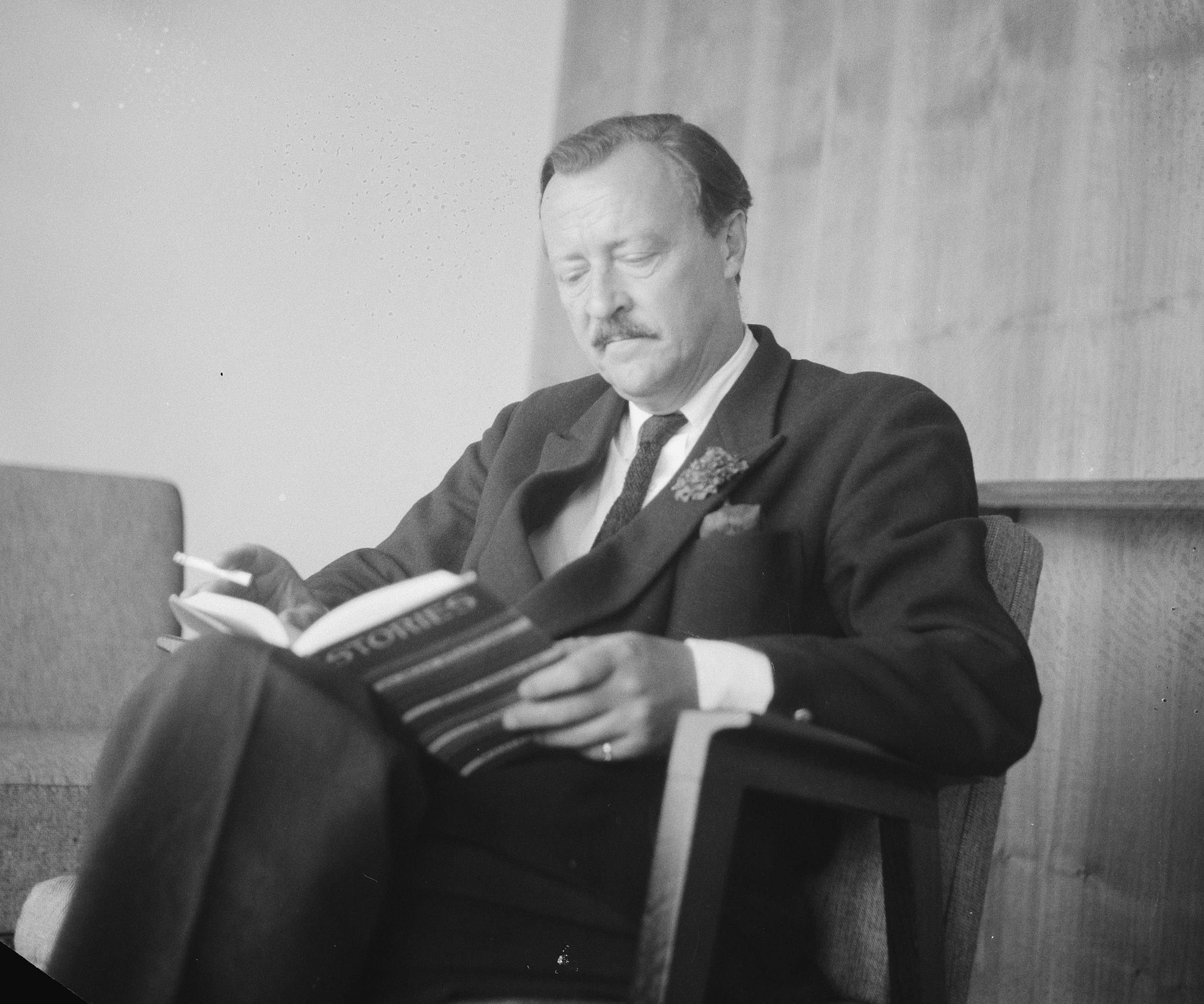

Lee’s museum career began during graduate school in 1939 when he worked as a volunteer assistant with Cleveland Museum of Art curator of Asian art Howard Hollis (1899-1995). In the early 1940s, Lee served as curator at the Detroit Institute of Arts. By 1944, like many of his generation, Lee joined the U.S. military, serving as a naval navigator in the Pacific theater during World War II. Lee spent the immediate postwar years in Occupied Japan as a head of the East Asian section of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAA) that worked with Japanese scholars and curators to search for and evaluate artworks, historical monuments, temples, gardens, and other cultural treasures in the country and recommend actions for their protection and preservation. Lee left Japan in 1948 to take up the dual position of curator and assistant director at the Seattle Art Museum. In 1952, Lee returned to the Cleveland Museum of Art as curator of Asian art, a role he retained even after becoming the museum’s director from 1958-83 (fig. 1).1

Fig. 1: Sherman Lee, c. 1952. Cleveland Museum of Art Archives

Through his collecting, exhibitions, and writings, Lee achieved prominence in the field of Asian art history during the second half of the twentieth century. Lee’s acquisitions of Asian art for museums in Detroit, Seattle, and Cleveland, as well as his collaboration with John D. Rockefeller III (1906–1978) and Blanchette Rockefeller (1909–1992), whose collection formed the core of the Asia Society Museum in New York, gave him a leading role in collecting during the postwar era. Lee’s involvement in major exhibitions and catalogues of Chinese, Japanese, Indian, and Southeast Asian art raised the profile of Asian art and promoted its appreciation by American museum audiences. With his widely-read survey book A History of Far Eastern Art, first published in 1964 and adopted up through the 1990s as an introduction for university students and the interested public, he helped to shape American and European understandings of Asian art.

During his first six years as curator of Asian art in Cleveland – beginning in 1952 – Lee acquired twenty-four Chinese paintings, many of which remain standards today. Although Lee managed to acquire some Chinese paintings during his years in Seattle in the late 1940s, director Richard E. Fuller’s (1897-1976) limited interest in and budget for these purchases left many works beyond reach.

While in Seattle, Lee obtained Chinese paintings mostly via dealers and collectors in Japan, especially through the museum’s arrangement with the dealer Mayuyama Junkichi 繭山順吉 (1913-1999) in Tokyo. By the time he arrived in Cleveland, however, many of the works that he had unsuccessfully recommended for Seattle had already changed hands in Japan and were no longer available. In Cleveland, he shifted his strategy toward acquiring paintings transmitted through Chinese, rather than Japanese, collections. Walter Hochstadter proved to be one of the main figures who helped Lee execute this strategy.

Walter Hochstadter grew up in the German city of Augsburg. In 1934, when he was twenty years old, he embarked on a yearlong journey through East Asia. He kept an extensive journal in which he described his experiences, particularly those that involved buying art and making connections with Chinese collectors and dealers (Fig. 2). At the end of his sojourn, Hochstadter remained in China and continued to establish himself as a collector of Chinese objects, particularly ceramics and paintings. By 1938, however, he had grown increasingly concerned about the worsening situation in Germany. In November that year, hundreds of Augsburg Jews were arrested and sent to Dachau. Hochstadter was Jewish and his parents were still in Germany. He began his activities as an art dealer in earnest, trying to raise enough money to get his parents out of the country. The American Consulate in Beijing granted him permission to come to the US in 1938, and he packed up his household goods and his growing art Chinese collection, sending it on to New York (Fig. 3).2 Shortly after his arrival, he rented an apartment in that city planning for his parents to reside there.

Fig. 2: Passport photograph of Walter Hochstadter, 1950. Leo Baeck Institute, Center for

Jewish History, New York, N.Y.

Unfortunately, his requests to admit his parents to the U.S. were denied. He tried to get his family to safety in Brazil, but that did not work out either. He finally succeeded in arranging for his parents to get to Italy in 1940. From there, they sailed to Shanghai, where, like many other Jews of the time, they found refuge. In April 1942, most of the remaining Augsburg Jews were sent to the Belzec, where many perished. At the end of the war in 1946, he finally got his parents to New York. His father, Hermann, died in 1965, but his mother Anna lived in Walter’s apartment until the grand old age of 90. Hochstadter developed relationships with many dealers in Beijing as well as in Shanghai and Hong Kong throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s. As a result, Hochstadter was well-positioned to buy objects from Chinese collections during a very tumultuous time in the country.3

From the time of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 through the War to Resist Japan from 1937 to 1945, the Guomindang government and the Communists were engaged in a civil war which ended with the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. These events prompted the sale of many Chinese artworks. The flow of objects, particularly paintings, spiked during the turmoil of the 1930s and 40s, when, in response to the increasing brutality of Japanese invaders, the collapse of the Chinese economy, and the anticipation of the expected consequences of a Communist victory, Chinese collectors and their families sold works to facilitate their own survival in a radically new reality. Other collectors left the country with some of their prized pieces. Some of them took refuge in Shanghai or the British colony of Hong Kong. Thus, many paintings from prestigious Chinese collections were suddenly available and priced to sell. Many of these works were purchased by Hochstadter and other dealers and later exported to Japan, Hong Kong, Europe, and the United States.

Fig. 3: Walter Hochstadter with customs agent Liu Ruifu, Beijing, 1938, Leo Baeck Institute,

Center for Jewish History, New York, N.Y.

Lee and Hochstadter first met in New York in 1940 when Lee was still a graduate student. Lee’s prior training in Chinese ceramics under James Marshall Plumer at the University of Michigan helped him garner a position assisting Howard Hollis in putting together a loan show of Chinese ceramics for Cleveland. On a trip to evaluate potential works for the exhibition, Lee and Hollis visited Hochstadter. Twelve years later, Lee turned to Hochstadter as one of the main dealers from which to acquire Chinese paintings. In 1953, Lee wrote about his enthusiasm and admiration for Hochstadter’s paintings, saying:

I do not flatter when I say that you are the only dealer who consistently shows me Chinese paintings that I like and want. This is unfortunate for my mental condition, which is reduced to despair by my inability to absorb as many of the things I should like to into our collection.4

The renowned early twelfth-century handscroll Streams and Mountains without End was one of the first, and perhaps the most significant, of Lee’s acquisitions from Hochstadter (Fig. 4). In the early 1950s, only a few Song dynasty (960-1279) paintings existed in American collections. Among that small number, most are dated to the Southern Song (1127-1279) and were transmitted through Japanese collections, including Li Anzhong’s 李安忠 (act. twelfth century) Hawk Pursuing a Pheasant acquired by Lee from Mayuyama Junkichi for the Seattle Art Museum in 1948. The majority of Northern Song paintings survived in the Chinese imperial collection. Many of the large hanging scrolls left mainland China for Taiwan in 1949, remaining inaccessible to most foreign scholars until the Chinese Art Treasures exhibition toured several American museums in 1961-62.5 A good number of Northern Song handscrolls left Beijing with the last Manchu emperor Pu Yi 溥儀 (1906-1967) in the 1920s, and eventually were transferred to the Liaoning Provincial Museum. Fortunately, during his stay in Japan in the 1940s, Lee had examined some Song paintings in Japanese collections. He had also developed a fondness for paintings formerly in the collection of Liang Qingbiao 梁清標 (1620-1691), whose seals he learned to recognize on scrolls, including the ones on Streams and Mountains without End. Lee acquired it during his very first year as curator for Cleveland. In 1953, the price of Streams and Mountains without End proved as dazzling as the picture itself. The $30,000 scroll was the single most expensive Chinese painting that Lee bought during the decade. Even so, it was still quite affordable compared with contemporaneous prices for European and American paintings.

Fig. 4: Streams and Mountains without End, c. 1100-50. Handscroll, ink and slight color on

silk; overall: 35.1 x 1103.8 cm; Gift of the Hanna Fund, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1953.126.

Lee’s experiences studying Chinese paintings in Japan early in his career led him to valorize Southern Song paintings over works from the later Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties (Fig. 5). By the early 1950s, however, Lee had changed his tune, turning to Hochstadter to purchase several seventeenth century scrolls for Cleveland including Wang Hui’s 王翬 (1632-1717) Tall Bamboo and Distant Mountains after Wang Meng from the esteemed collection of Shanghai connoisseur Pang Yuanjji 龎元濟 (1864-1949), Xiao Yuncong’s 蕭雲從 (1596-1673) Pure Tones among Hills and Valleys, and Bada Shanren’s 八大山人 (1626-1705) understated classic Fish and Rocks (Fig. 6).6 Changes in the art market such as Japan’s Cultural Property Protection Act of 1950, which Lee and other members of the MFAA helped shape, placed additional restrictions on the export of artworks, and the exchange rate for dollars to yen became much less favorable for American buyers. The Act applied to both Japanese and Chinese art in Japan.

Fig. 5: Sherman Lee with Japanese colleagues, Japan, 1947. The Cleveland Museum of Art

Archives.

Hochstadter also sold paintings to the Art Institute of Chicago, the Honolulu Academy of Arts (now Honolulu Museum of Art), the St. Louis Art Museum, the Toledo Museum of Art, Massachusetts collector Richard B. Hobart (1886-1963), pharmaceutical magnate Eli Lilly (1885-1977) in Indianapolis, and Chinese painter and collector Wang Jiqian 王季遷 (1907-2003), commonly known as C.C. Wang. In Europe, Zurich collector Charles Drenowatz (1908-79) and the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (now: Museum für Asiatische Kunst, located at the Humboldt Forum) in Berlin bought paintings from Hochstadter.7 Lee, on behalf of the Cleveland Museum of Art, managed to acquire the most paintings from Hochstadter’s collection of any museum: a total of twenty-seven paintings came to Cleveland between 1952 and 1971.8

Fig. 6: Bada Shanren (1626-1705), Fish and Rocks, mid to late 1600s. Handscroll, ink on

paper; overall: 29.2 x 157.4 cm; John L. Severance Fund, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1953.247.

Lee’s acquisitions of paintings from Hochstadter in the 1950s was also facilitated by other curators’ inability to make purchases. German Sinologist and art historian Ernst Aschwin Prinz zur Lippe-Biesterfeld, commonly known as Aschwin Lippe, arrived at the Metropolitan as a senior research fellow in 1949 (Fig. 7). Lippe studied at the University of Berlin and completed a dissertation on Li Kan’s 李衎 (1245-1320) treatise on bamboo painting in 1942.9 Soon after he reached New York, he began making the rounds to dealers and private collectors. Materials in Lippe’s surviving papers indicate his evaluation of numerous Chinese paintings as early as 1950, when he became associate curator of “Far Eastern Art.”10 He kept detailed notes including titles, attributed artists, colophons, and seals as well as prices and his own quality ratings. Lippe wanted to acquire some of Hochstadter’s paintings to improve the Metropolitan’s holdings. In the 1950s and 1960s, the museum’s Chinese painting collection was quite weak after two major purchases from John C. Ferguson in the 1910s and Abel William Bahr (1877-1959) failed to significantly boost its caliber.11 Lippe and Hochstadter met many times during the 1950s and early 1960s. As early as 1952, Lippe made notes on paintings from Hochstadter’s collection and kept regular track of which works he sold to other museums and private collectors. Lippe’s repeated clashes with Alan Priest, who was in charge of the museum’s Asian department from 1928-1963, prevented him from successfully recommending acquisitions from Hochstadter. For instance, in a two-part internal memo from 1955, deceptively titled “Friendly Notes on Aspects of Chinese Painting,” Lippe offered a scathing rebuke of Priest’s 1954 book:

Fig. 7: Aschwin Lippe, July 1961. Fotocollectie

Anefo, National Archives of the Netherlands.

The first batch of notes was mainly concerned with the purposely scarce bits of factual information contained in your book. Considering that there is so little of it, it contains, I feel, too much misinformation. Now I am going to step on your feet in the matter of attributions and your approach to this subject. . . . I feel that you do not, on the whole, bother to check whether something you want the museum to acquire really is the best of its kind, whether it is authentic, whether it has or can be given a pedigree. And why should you, if you do not care who painted it and when?12

In 1957, Lippe made a valiant effort to convince the museum to support the purchase of a Bada Shanren painting from Hochstadter’s collection. He planned to bring the painting before the trustees while he had authority as acting curator, since Priest was away traveling in Asia. Lippe believed he had the support of museum director James Rorimer (1905-1966). A delay in the planned trustee meeting until early December, however, allowed Priest to return in time to “right away put a spoke in the wheels” and eventually scuttle the purchase.13 Understandably frustrated, Lippe told Hochstadter that he had not given up.

I must not let this discourage me . . . We will try again! . . . But I cannot easily get over the fact that the Bada Shanren has slipped through my fingers. . . . I am writing to you about this, because I trust your discretion and because I would like you to understand how the situation here was and that I have not misled you, but, on the contrary, that I have done everything that I could—with considerable risk.14

Hochstadter kept trying to work with Lippe, particularly in the late 1950s when he found himself cash-strapped because of newly-enforced restrictions on importing Chinese paintings into the United States related to the Trading with the Enemy Act. Hochstadter also eagerly anticipated Priest’s retirement from the museum in 1963. Thus, he stepped up his efforts to arrange a purchase of a group of fifteen Ming and Qing paintings in early 1962.15 Despite Lippe’s earlier failure to acquire one of Hochstadter’s pictures, he pressed on saying:

With regard to our friendly relationship as well as to the fact that I consider you to be one of the few, really serious curators in this field (that you have not been able to achieve anything so far, in spite of best intentions, but also due to unpleasant impediments, is, after all, not your fault) . . . If you can secure these for your museum, you will have—in spite of all neglects of the last years—the best museum collection of this important and interesting epoch . . .16

By January 1963, after it became clear that Lippe would not be promoted as Priest’s replacement, he announced his resignation from the museum.17 In the years that followed, Lippe shifted much of his scholarly focus to South Indian sculpture. After he moved to Paris, he continued to do work for the Metropolitan as a research curator of Indian art from 1965 to 1973. Lee pointed out the museum’s missed opportunities with Lippe in his obituary for him in 1989: “Unfortunately his interest in and knowledge of wen-ren painting was not used in the development of the then dormant Chinese painting collection.”18

Fig. 8: Li Shizhuo (1690-1770), Landscape After Jing Hao and Guan Tong, c. 169-1770.

Hanging scroll, in on paper; overall: 226.7 x 68.6 cm; John L. Severance Fund, Cleveland Museum of Art, 1952.588.

Lee’s first purchase from Hochstadter for Cleveland was Landscape After Jing Hao and Guan Tong by Li Shizhuo 李世倬 (1690-1770) (Fig. 8). Although Hochstadter sold the scroll to Lee in 1952, the work initially arrived in the United States under the auspices of the Chinese dealer C.T. Loo 盧芹齋 (1880-1957) in January 1949. In 1950, Frank Caro took over C.T. Loo’s New York gallery following a final liquidation sale (Fig. 9).19 Despite the closeout, several hundred Chinese objects, including the Li Shizhuo painting, remained with Caro. Dealer catalogues and business records indicate that Chinese painter and collector C.C. Wang 王季遷 (1907-2003) often provided authentications for paintings that Loo and Caro hoped to sell. In other cases, dealer’s inventory cards indicate that particular paintings were “taken by C.C. Wang,” likely as compensation for his consulting services. Thus, the Li Shizhuo scroll was part of a group of works that passed to C.C. Wang shortly after its arrival in America. In addition to the seals of Chinese collectors going back to the nineteenth century, Wang’s seal also appears on the painting.20 Hochstadter and Wang exchanged paintings with one another on several occasions. Thus, it’s likely that Hochstadter acquired the Li Shizhuo painting from Wang and subsequently sold it to Lee.

During his first five years in Cleveland, Lee acquired three paintings directly from Caro. Like Hochstadter, Caro’s inventory of Chinese paintings consisted of works transmitted through Chinese collections: the type of works that Lee aimed to acquire in the 1950s. Lee’s purchase of Leisure Enough to Spare by Yao Tingmei 姚廷美 (act. mid fourteenth century) exemplifies Lee’s successful strategy, initiated in the 1950s, of buying Yuan dynasty paintings that others had hesitated to select (Fig. 10). Loo bought this painting and several dozen others from the highly-respected Shanghai collector Zhang Heng 張珩 (1915-1963), better known as Zhang Congyu 张葱玉, around 1947-48. Loo’s New York gallery held An Exhibition of Authenticated Chinese Paintings in April 1948 that featured twenty pictures from the collection, for which C.C. Wang wrote the short descriptions and “authentications.”21 Loo introduced the show, obviously operating as a sale, in typically grandiose fashion, emphasizing the paintings’ transmission through Zhang’s esteemed collection:

It seems to us that up to today most of the fine paintings in this country came out of China individually and some accidentally. This is the first time that a collection of this class of art ever came out which was gathered by a real connoisseur. It has been studied according to Chinese tradition, with full research in past publications and with the colophons and seals on each painting authenticated.22

Fig. 9: Left to right: C.T. Loo, Aschwin Lippe, Frank Caro, and Alan Priest, New York, N.Y.,

1950. Photograph by Nina Leen/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images.

Lee visited the show in New York while he was affiliated with the Seattle Art Museum. Because the prices ranged from a low of $4,000 and a high of $35,000, Lee had little chance of convincing Fuller to support such expensive pictures for Seattle, particularly since he had already proposed a slate of more affordable Chinese paintings from Japan at the time.23

Leisure Enough to Spare arrived in the United States from China in November of 1948, several months after Loo had purchased the majority of Zhang Congyu’s collection, and too late to include it in the April exhibition. Records indicate the painting did not come directly from Zhang but was purchased from a Mr. Tai and facilitated by an agent in China who received a separate commission.24 Loo first offered the painting to curator Charles Fabens Kelley (1885-1960) at the Art Institute of Chicago in February 1949 for $8,000.25 After several months, Kelley returned Leisure Enough to Spare and, in June 1951, the picture was offered to Asian art curator Laurence Sickman (1907-88) at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City for $500 less. Sickman retained the painting for almost nine months before sending it back to New York. Two years later, Caro offered the picture to New York collector and Finnish émigré Ernest Erickson (1893-1983) for far less. Erickson’s tastes leaned toward early Chinese works such as small jades, bronzes, and silver, rather than paintings, so he passed on the picture after only two days.26 After visiting Caro’s gallery early in 1954, Lee asked him to send about a dozen paintings to Cleveland, including Leisure Enough to Spare, for purchase consideration as well as possible inclusion in Lee’s Chinese Landscape Painting exhibition which opened later that year.27 Yao’s scroll was Lee’s first purchase from Caro.28 And since it had already been circulating on the market for several years, Lee managed to acquire it for a quite reasonable price of $5,200.

Fig. 10: Yao Tingmei, Leisure Enough to Spare, 1360. Handscroll, ink on paper; overall: 23.8

x 734 cm; John L. Severance Fund, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1954.791.

The timing of Lee’s purchase of Leisure Enough to Spare proved fortuitous. Yuan paintings by well-known early masters such as Zhao Mengfu 趙孟頫 (1254–1322), Qian Xuan 錢選 (1239–1301), and the famous quartet of late masters comprised of Ni Zan倪瓚 (1306–1374), Wang Meng 王蒙 (1308–1385), Huang Gongwang 黃公望 (1269–1354), and Wu Zhen 吳鎮 (1280–1354) attracted the interest of Chinese, American, and European collectors throughout the twentieth century. Though Lee also sought out works by these renowned artists, his open-mindedness toward compelling works by lesser-known artists like Yao Tingmei gave him an advantage in building a significant collection of Yuan paintings for Cleveland over the next three decades.

Research on the history of collecting Chinese paintings has understandably focused on the inscriptions, colophons, and seals attached to the paintings themselves. By considering pre-modern painting collection catalogues as well as seals, inscriptions, and colophons, it is possible to reconstruct some of the provenance and reception history of a number of surviving Chinese paintings. However, since most twentieth century Japanese, European, and American collectors and dealers did not add seals or colophons to Chinese paintings, one has to look at external sources to extend the biographies and itineraries of these objects into the twentieth century. Dealer business records and correspondence held in archival collections not affiliated with museums such as the Frank Caro Archive and the Walter Hochstadter Papers provide scholars with valuable information on pricing, circulation, and relationships. Because it is part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives regularly grant researchers access to its many collections of personal papers of important curators such as Aschwin Lippe, James Cahill (1926-2014), and John Alexander Pope (1906-1982). In my own research, I was able to consult Sherman Lee’s personal papers that had been preserved by his family. And, unlike many exhibition catalogues then and now, Eight Dynasties of Chinese Paintings: The Collections of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and The Cleveland Museum of Art from 1980 includes provenance information on many of the included pictures.29

Many art museums in the United States have, however, until quite recently, been reluctant to share their materials related to provenance on Chinese works in their collections with individuals not employed by their institution. In 1999, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) established guidelines for its member museums to identify artworks, potentially subject to restitution claims, in their collections with an explicit focus on un-restituted artworks confiscated by the Nazis between 1933-45.30 In the United States, new provenance research initiatives began in 2000, with museums focusing almost exclusively on European paintings in their collections. Additional stages of provenance research have also addressed archaeological material, with most American museums providing provenance documentation on acquisitions of archaeological material and works of ancient art since 2008 on the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) registry website—which includes objects from China.31

Nonetheless, when I began researching the twentieth-century provenance of Chinese paintings in American museums in 2010, only a few museums permitted “outside” scholars with access to such information. While the Freer|Sackler launched a website on its World War II Provenance Project in 2009 on Asian art, most other American museums have, understandably, been slower to turn their attention to sustained provenance research on Chinese art.32 While provenance information about objects in museum collections can be sensitive in terms of pricing and potential cultural property issues, scholarly provenance research on Chinese paintings in American collections does not, typically, relate to potential restitution claims nor does it seek to sensationalize.

The last few years have brought welcome changes. Through its collaborative online scholarly catalogue Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, the Seattle Art Museum became one of the first museums to share provenance information on Chinese paintings with scholars and the public.33 The series of colloquia held under the auspices of the German-American Provenance Research Exchange Program (PREP) from 2017 to 2019 brought together curators and institutionally-affiliated provenance researchers with scholars and independent researchers, including specialists on Chinese art.34 In addition, several museums including the Cleveland Museum of Art (2018) and the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (2020) have also started to include some provenance information on their websites. Provenance research remains an important avenue for expanding our understanding of the history of the art market as well as the history of collecting and reception of Chinese paintings in the twentieth century and beyond. Increasing collaboration between scholars and museum professionals specializing in Asian art holds great promise for the years to come.

Noelle Giuffrida is a professor of Asian art at the School of Art at Ball State University and curator of Asian art at the David Owsley Museum of Art (DOMA). She is also a research associate with the Center for East Asian Studies at the University of Kansas.

1 For more on Lee’s career and his collecting of Chinese art for American museums, see Noelle Giuffrida, Separating Sheep from Goats: Sherman E. Lee and Chinese Art Collecting in Postwar America (Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2018).

2 Höchstädter’s name was Americanized when he came to New York and umlauts were not included thereafter.

3 The main source for information on Hochstadter is Walter Hochstadter Papers, 1876-2002, Leo Baeck Institute, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY (https://archive.org/details/walterhochstadte02hoch/mode/2up ). Also see: Mary Ann Rogers, The Passing of Friends in Kaikodo, in Journal 25 (Spring 2009), 12-14.

4 Sherman Lee to Walter Hochstadter, 9 February 1953, folder 17, box 3. Walter Hochstadter Papers Leo Baeck Institute, Center for Jewish History, New York, NY.

5 For more on this exhibition see: Noelle Giuffrida, The Right Stuff: Chinese Art Treasures’ Landing in 1960s America in Michelle Y.L. Huang, ed., The Reception of Chinese Art Across Cultures (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2014), 201-28 and Li Lin-ts’an, Guo bao fu mei zhanlan riji 國寶赴美展覽日記 (Diary of the National Treasures Exhibition in America) (Taipei: Shangwu, 1972).

6 Hochstadter acquired works that were once part of famous Chinese collections such as those of Pang Yuanji and Chang Dai-chien 張大千 (1889-1983). However, he did not purchase them directly from the collectors or their families. Instead Chinese dealers, chiefly in Shanghai and Hong Kong, served as intermediaries. Invoices with vague seals or oddly romanized Chinese names have, so far, made it difficult to determine the identities of these dealers.

7 The Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst acquired its paintings from Hochstadter mainly between 1962 and 1975, see Lothar Ledderose, Orchideen und Felsen. Chinesische Bilder im Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Berlin (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preussischer Kulturbesitz, 1998), particularly cat. nos. 2; 6; 19; 21; 22; 23; 27; and 67. Hochstadter engaged in the unfortunate practice of splitting up the leaves of a single album and selling leaves to different museums and private collectors. For instance, paintings from the same album by Kuncan 髡殘 (1612-1673) are now in the Cleveland Museum of Art (1966.367), the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (1965-22), and the British Museum (1963,0520,0.3).

8 Lee’s purchases through Hochstadter can be divided into three eras: 1) 1952-57: eleven paintings; 2) 1958-69: thirteen paintings; and 3) 1970-71: three paintings. For instance, see Wai-kam Ho, Sherman E. Lee, Laurence Sickman, and Marc F. Wilson, Eight Dynasties of Chinese Paintings: The Collections of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, and The Cleveland Museum of Art (Bloomington, IN: Cleveland Museum of Art and Indiana University Press, 1980), catalogue nos. 21; 46; 108; 123; 145; 155; 160; 194; 198; 199; 204; 206; 208; 216; 223; 233; 235; 236; 228; 231; 245; 248; 251; 265; and 277. Several of the paintings from Hochstadter have not been published in catalogues.

9 Aschwin Lippe, Li K’an und seine ‘Ausführliche Beschreibung des Bambus,’ Beiträge zur Bambusmalerei der Yüan-Zeit, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift NF 18, Jhrg. Heft 106 (1942-1944).

10 The Aschwin Lippe Collection, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. These papers were not yet processed at the time of author’s research in October 2012.

11 Ferguson acquired paintings for the museum from 1912 to 1914. See John C. Ferguson, Special Exhibition of Chinese Paintings from the Collection of the Museum Catalogue (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1914). On Ferguson’s buying for the Metropolitan, see Lara Jaishree Netting, A Perpetual Fire: John C. Ferguson and His Quest for Chinese Art and Culture (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2013), 71-91. Priest, Horace Jayne, and Henry Francis Taylor (1903-1957) were involved in the acquisition of the Bahr paintings for $355,000 between 1933 and 1947. See Memo from Alan Priest to Herbert Winlock, 14 January 1933, Bahr, A.W. Collection, 1933, Office of the Secretary Records, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York (MMAA); Correspondence from Horace Jayne to A.W. Bahr, 29 September 1941, Bahr A.W. – Benefactor, 1916, Office of the Secretary Records, MMAA; and Index cards for A.W. Bahr purchase, ca. 1947, Box 68, Folder 1, Office of the Registrar records, MMAA.

12 Lippe to Priest, Friendly Notes on Aspects of Chinese Painting, Part II, 31 October 1955, Lippe Collection, Freer|Sackler Archives.

13 Lippe to Hochstadter, 15 February 1957, Box 3, Folder 16, Walter Hochstadter Papers. Translation by Enno Lohmeyer from the original German.

14 Lippe to Hochstadter, 15 February 1957, Walter Hochstadter Papers.

15 This group included several leaves from Shen Zhou’s Tiger Hill album and a section of Zhou Chen’s Beggars and Street Characters, both of which Lee acquired in 1964.

16 Hochstadter to Lippe, 28 March 1962, Lippe Collection, Freer|Sackler Archives. Translation by Enno Lohmeyer from the original German.

17 Lippe to Hochstadter, 8 January 1963, Box 1, Folder 3, Walter Hochstadter Papers.

18 Lee, Aschwin Lippe, 1914-1988 in Archives of Asian Art 42 (1989), 84.

19 Loo: “Dealing in Chinese antiquities was at its end and that I would be deprived of all my enjoyment.” C.T. Loo, C.T. Loo, Inc. Announcement of Liquidation in Art News (May 1950), 3. This followed another “clearing sale” held in 1941-42 of at least 1,000 objects. See Daisy Yiyou Wang, C.T. Loo and the Chinese Art Collection at the Freer, 1915-1951, in Arts of Asia (October 2011), 104-106.

20 On C.C. Wang’s role as a collector and connoisseur, see Kathleen Yang. Through a Connoisseur’s Eye: Private Notes of C.C. Wang (Beijing: Zhonghua Books, 2010) and Xu Xiaohu徐小虎 (Joan Stanley-Baker). Huayu lu: Wang Jiqian jiao ni kandong Zhongfuo shu hua 畫語錄:王季遷教你看懂中國書畫 (C.C. Wang Reflects on Chinese Calligraphy and Painting) (Taipei: Artco Books, 2013).

21 This exhibition also traveled to Minneapolis in June and July of 1948.

22 An Exhibition of Authenticated Chinese Paintings. show booklet, CT Loo, April 1948, unpaginated introduction.

23 Lee wrote down prices and the characters for Chinese cyclical dates in his copy of the booklet. I am grateful to Katharine Lee Reid for sharing her father’s personal copies of many important materials with me.

24 Inventory card, 46280, G-9115; Landscape with a man seated by a small waterfall and a house near a river and mountain background, Frank Caro Archive, Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

25 Kelly purchased at least two paintings from Loo in 1950 and 1952 including Xiang Shengmo’s 項聖謨 (1597-1658) Bamboo-Covered Stream in Spring Rain (AIC 1950.2) and Xia Chang’s夏昶 (1388-1470) River and Mountain Landscape (AIC 1952.7).

26 Much of Erickson’s Chinese collection was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1985. Four of Erickson’s Chinese paintings reside at the Metropolitan, including Tang Di’s唐棣 (1287-1355) Landscape After a Poem by Wang Wei 摩詰詩意 (1985.214.147). Other pieces made their way to museums in Sweden. For more on Erickson, see Maxwell K. Hearn, Ancient Chinese Art: the Ernest Erickson Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), 9, 13-26, and Jan Wirgin and Ulf Abel, The Ernest Erickson Collection in Swedish Museums (Stockholm: Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, 1989), and Bo Gyllensvärd, Some Chinese Paintings in the Ernest Erickson Collection (Stockholm, 1964).

27 For more on this exhibition, see Noelle Giuffrida, Collecting and Exhibiting Chinese Paintings in Postwar America: Sherman Lee and the 1954 Chinese Landscape Painting Exhibition, in Jason Kuo, ed., Chinese Calligraphy and Painting Studies in Postwar America (New Academia Publishing, 2020), 85-118.

28 Lee ended up acquiring four paintings from this Caro group over the next decade.

29 See Wai-kam Ho, Sherman E. Lee, Laurence Sickman, and Marc F. Wilson, Eight Dynasties of Chinese Paintings.

30 See: https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/unlawful-appropriation-of-objects-during-the-nazi-era.

31 See: https://aamd.org/object-registry/new-acquisitions-of-archaeological-material-and-works-of-ancient-art/browse.

32 The Freer|Sackler Museums have continued to share a wealth of provenance and curatorial information on Chinese paintings in their collection. For instance, see the online catalogue for their Song and Yuan paintings and calligraphy at: https://asia.si.edu/publications/songyuan. Indeed, the museums’ website now provides such information on a majority of works in their collections.

33 See: http://chinesepainting.seattleartmuseum.org/OSCI/start?t:state:flow=83f15be6-1eb7-43fa-85db-9dba15e30b63. Even though provenance information is included, unfortunately, it is not possible to search for names of collectors and dealers. Also see the object-based catalogue: Josh Yiu, A Fuller View of China: Chinese Art at the Seattle Art Museum (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014).

34 See https://www.si.edu/events/prep.