ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Niklas Leverenz

The Looting of the Winter Palace in Peking

in 1900-1901

An anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising began in northern China in 1899, dubbed the “Boxer Rebellion” by the foreign powers that subsequently invaded China. In the course of events, troops of the Eight-Nation Alliance began to arrive in Beijing in August 1900 and occupied the city. During this time countless works of art were looted and many of these were subsequently traded on the international art market. A significant number of these were originally housed in the Ziguang Ge (紫光閣, Hall of Imperial Splendour), and their dispersal is a key subject of the present article.

The Ziguang Ge was part of an imperial park to the west of the Forbidden City called the “Winter Palace” by Europeans. This area was given to the Germans as headquarters for the commander-in-chief for the coalition army under the command of Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee (1832-1904). Contemporary publications demonstrate how the German army settled in this area and how German soldiers treated artworks located there as their property. It is therefore not surprising that many works of art from this area are either in German museum collections today or have entered the art market from German collections. As the Ziguang Ge housed specific artworks, paintings, and other works of art with military motifs, their origin and whereabouts can be easily documented. Systematic efforts on the part of the Chinese to locate these works of art do not seem to have been made to date. It is to be hoped that at least the two large collections of officer paintings now in Chinese hands will one day be made accessible to the Chinese public.

An anti-foreign and anti-Christian uprising began in northern China in 1899. Dubbed the “Boxer Rebellion” or the “Boxer Uprising” by Europeans, given that one of the names of the movement, Yihequan (義和拳), translates literally as “Righteous and Harmonious Fists”, the rebels invaded Beijing in June 1900, causing Chinese Christians and Western diplomats to take refuge in the Legation Quarter, just southeast of the Forbidden City (fig. 1). The Dowager Empress Cixi (Cixi Taihou 慈禧太后) initially supported the rebels with Qing imperial troops and on 21 June issued an Imperial Decree declaring war on the Western troops who had invaded China to lift the siege. Troops of the Eight-Nation Alliance (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, and the United States) began to arrive in Beijing in August and ultimately lifted the siege, which had lasted for 55 days.1 As a result of the occupation of Beijing, countless works of art were looted all over the city and many were subsequently traded on the international art market.2 A significant number of these were originally housed in the so-called Hall of Imperial Splendour, and their dispersal is a key subject of the present article.

Fig.1: City map of Beijing in 1900

Above, the Inner City, with the walled Imperial City and the Forbidden City in orange; right, the city gates attacked by foreign armies (Japan, Russia, USA, Great Britain); the Legation Quarter in red, southeast of the Forbidden City; Hatamen, Qianmen - the two city gates captured first, located just south of the Legation Quarter

Map in the public domain, with revisions by the author.

The first foreign troops advanced on Beijing in the early morning of 14 August 1900. From the east, the Japanese and the Russians came up against the city wall of the Inner City (the Tartar City), which would be defended by Chinese troops until the afternoon. Further south, the English and Americans came upon the less well-defended city wall of the Outer City (Chinese City), where they were eventually able to capture the Hatamen Gate and the Qianmen Gate and liberate the Legation Quarter by noon.

French troops reached Beijing in the afternoon of 14 August. By the time the German, Austrian, and Italian troops reached Beijing four days later on 18 August, the first great wave of looting was already over. The city was subsequently divided up into administrative areas among the eight countries that had sent armies to Beijing, essentially the same area first entered by the soldiers of each respective country.

Furthermore, Germany was granted the right by the other nations to nominate a commander-in-chief for the coalition army of the eight occupying countries in the person of Field Marshal Alfred Graf von Waldersee (1832-1904). On 20 June 1900, the German envoy Clemens von Ketteler (1853-1900) had been shot dead in the street in Beijing, and the appointment of Waldersee thus recognized Germany’s outstanding interest in reparations.

On 17 October 1900, two months after the occupation and division of the city among the foreign powers, Waldersee arrived in Beijing. Since suitable headquarters were needed for him, the English and Americans agreed to cede to the Germans a separately walled area occupied by them west of the Forbidden City around the southern and middle of the three lakes (fig. 2). Part of this area, which was then called the “Winter Palace” by Europeans, was an imperial garden-palace complex known as the Zhongnanhai (中南海), literally the “Central and Southern Seas”, which contained among other constructions a palace built for the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908). When the Germans took over this area, American and English flags were still attached to many houses.3 The Cixi palace complex itself had previously been occupied by Russian soldiers.4

Fig. 2 (left): The occupying forces in 1900 around the Forbidden City (which remained unoccupied). To the left Germany (pink), then clockwise France (blue), Russia (also pink), Japan (brown) and England (yellow).

Contemporary hand-coloured print (private collection).

Fig.3 (right): The area of the ‘Winter Palace’ on the southern and middle lakes of the Zhongnanhai.From Deutschland in China 1900-1901: Bearbeitet von Teilnehmern der Expedition... (Düsseldorf, Druck August Bagel, 1902), 152.

Fig.4 (left): To the right the residence of Cixi, to the left the “asbestos house”

From Deutschland in China 1900-1901: Bearbeitet von Teilnehmern der Expedition... (Düsseldorf, Druck August Bagel, 1902), 154.

Fig. 5 (right): Detail of map of the ‘Winter Palace’, seat of the High Command and residence of Waldersee. The shaded part burned on the night of 17-18 April, 1901.

Detail of Fig. 3.

The building Waldersee took as his residence was located in a complex of buildings on the west bank at the transition from the southern to the middle lakes. German soldiers of the high command took up quarters in the surrounding buildings and temples. From all these buildings, countless works of art were looted, many of which are in German museum collections today.

Waldersee initially intended to live in the main hall of Cixi’s palace, the Yiluan Dian (儀鸞殿, Ceremonial Crane Hall), which is marked as B on the map above (fig. 3), in the shaded area at the southwest corner of the middle lake. However, while the houses’s wood carvings were admired by his contemporaries, it proved too cold for him, so he moved to a residence that could be more efficiently heated (the so-called “asbestos house”) located directly to the south (fig. 4).5

This house burned down completely in the night of 17-18 April 1901. In the fire not only was Major General Gross von Schwarzhoff (1850-1901) killed, but the surrounding buildings were also destroyed, including Cixi’s residence; see the shaded part of the map above (Fig. 5).

Fig. 6: The area of the Winter Palace that burned in 1901, formerly home to the headquarters including the apartment of Waldersee and numerous officers.

Der Ostasiatische Lloyd No. 16, 19 April 1901.

Waldersee had been joined in the part of the Winter Palace that burned down by numerous other German officers of the high command who also bivouacked there. The German-language newspaper Der Ostasiatische Lloyd, published in Shanghai, included a map of the burned-down part of the Winter Palace in its 19 April 1901 issue (fig. 6). It noted the names of the other officers, indicating their specific places of residence; on the left, from bottom to top: Lieutenant v. Rauch, Adjutant Captain Wilberg, Major von Brixen, Lieutenant Colonel von Böhm; and on the right, from bottom to top: Major General Gross von Schwarzhoff, Major General von Gayl, above, officers’ apartments. After the fire, Waldersee moved again, this time into the building marked C on the map in fig. 5, along the centre of the shoreline facing the Southern Sea.

The residents here and other German officers possessed works of art which they had either looted themselves or bought from other looters in Beijing. In 1901, Major General v. Gayl gave a temple bell from the Winter Palace to Friedrich Wilhelm Karl Müller (1863-1930), assistant director of the institution known at that time as the Völkerkundemuseum (today: Ethnologisches Museum or Ethnological Museum) of Berlin. Müller was in Beijing from 6 April to 13 September 1901 to purchase art for the museum. During this time, he also met frequently with Waldersee and maintained good relations with his officers, some of whom had received language lessons from Müller the year before in preparation for their departure for China.

A considerable part of the art works that Müller brought back to Berlin were acquired through these officer contacts. In a report written after his return to Berlin, Müller mentions that some officers were almost enthusiastic about supporting his purchasing mission for the museum. In 1901, Müller sent 117 crates back to Germany containing objects that came mainly from different locations of the Winter Palace.

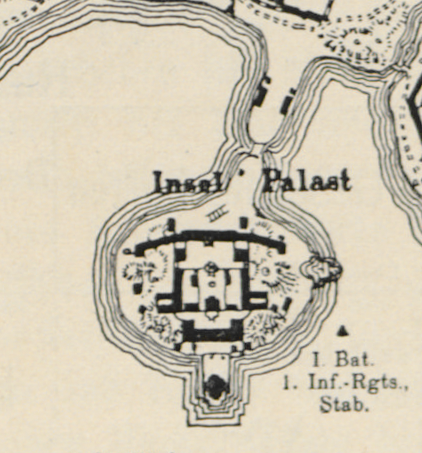

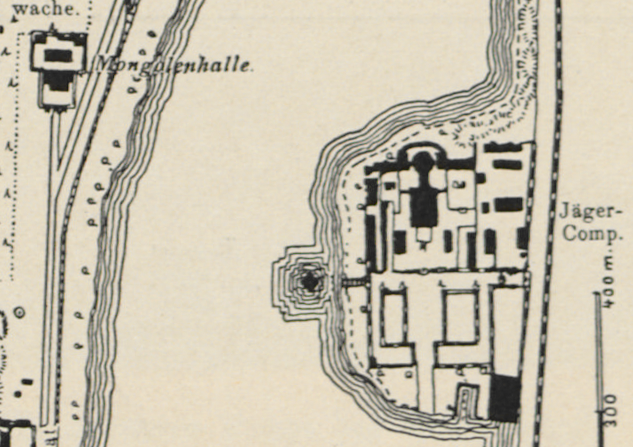

Müller specifically names, among other things, objects that came from the Sea Palace (Insel-Palast), an artificial island called the Yingtai (瀛臺) in Chinese, in the southern of the three lakes (fig. 7), and the Hunter’s Temple (Jäger-Tempel) on the east side of the middle lake (fig. 8).

Fig. 7: Detail of Fig. 3, ‘Sea Palace’, seat of the 1st Battalion and the 1st Infantry Regiment.

In his report, Müller described the Sea Palace as follows:

[I visited the] Sea Palace in the Southern Lotus Lake, where the emperor was imprisoned for a while. I was shown the remains of a wall in front of the stairs that lead outside. Inside the palace only a little of its interior was left. Even the carillon made by the Jesuits under the K’ang-hsi emperor, which added so much to the popularity of the Jesuits at the Chinese court, was almost entirely stripped of its bells.6

The Hunter’s Temple (see fig. 8, right) is called the Wanshan Dian (萬善殿) in Chinese, which translates as “Hall of Ten Thousand (i.e., countless) Virtues”. The temple was given the name Hunter’s Temple because the German Hunter’s Battalion had taken up quarters there. One of the outstanding works of art in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, the painting The Buddha Preaching, comes from this temple.7

Fig. 8: Detail of Fig. 3, Jägertempel (Wanshan Dian) on the right and Mongolenhalle (Ziguang Ge) on the left.

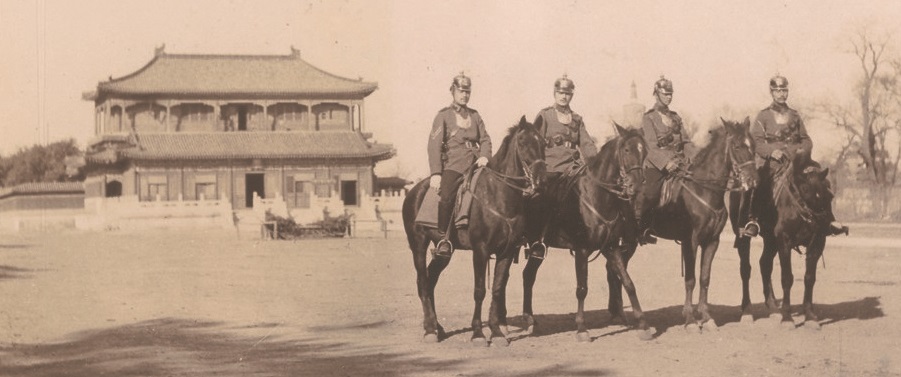

However, the largest volume of looted works of art originated from what the Germans dubbed the Mongolenhalle (Mongolian Hall, see fig. 8, left side) opposite the Hunter’s Temple on the west side of the central lake. The Mongolian Hall is properly called the Hall of Imperial Splendour (Ziguang Ge 紫光閣) and is the place where the Qing emperors celebrated their military victories and received foreign guests (fig.9). Especially during the reign of the Qianlong emperor (r. 1735-1795), victory banquets for returning armies were held here from 1761 onwards after every successful military campaign.

The Hall of Imperial Splendour held hundreds of paintings and other works of art with military motifs. Only a few paintings once housed there are still in China today, but foreign, especially German, museums consider them important parts of their collections. Over one hundred of these art works have appeared on the international art market since the Boxer Rebellion. The looting of Beijing in 1900-1901 and the subsequent distribution of these pieces of art can be documented particularly well by the works themselves.

Fig. 9: Hall of Imperial Splendour about 1900, with German soldiers in the foreground

Photo courtesy Bonham’s

Müller visited the Hall of Imperial Splendour in 1901, but apparently did not take anything from the almost empty building. According to his report, he had bought the military paintings he brought back to Germany from soldiers in Beijing. Müller describes his visit to the hall as follows:

The Mongol Palace in the Middle Lotus Lake had been utterly plundered. No trace of the old armour that was once kept there remained. The 200 portraits of generals and statesmen of the Ch’ien-lung emperor, of which the 18th-century Jesuits told us such interesting details, had been scattered to the winds. With considerable effort, I tracked down two of them in Beijing. The text on these paintings in Manchu and Chinese was written by the Ch’ien-lung emperor himself. Of the battle paintings, which this emperor had commissioned, only the explanatory texts, written by the emperor himself, were left.8

Furthermore, another contemporary witness, a certain Di Baoxian from Shanghai, the owner of the newspaper Shih-bao (時報) or The Eastern Times, visited Beijing in early 1901 and described the situation in the Hall of Imperial Splendour as follows:

Fig. 10: Hall of Imperial Splendour ca. 1901, the upper floor without exterior walls

Photograph, private collection.

In Ziguang Ge, books were strewn everywhere, and the interior walls of the ground floor still bore depictions of General Zuo Zongtang crushing the Tongzhi Hui Revolt and General Li Hongzhang suppressing the Nian Rebellion. As for the portraits of those who had rendered outstanding service to their country, it was impossible to know if they still existed since the staircase had been destroyed and the upper floor could not be viewed.9

Di Baoxian seems to have been in the Hall of Imperial Splendour later than Müller, as he describes a destroyed staircase that Müller did not mention. In fact, the Hall of Imperial Splendour suffered considerable destruction during 1901 (fig. 10). A photograph from the album of a German soldier shows the Hall of Imperial Splendour with the outer walls on the upper floor largely missing. Since there was no fighting in this area after the occupation, only looting or vandalism can have been the cause.

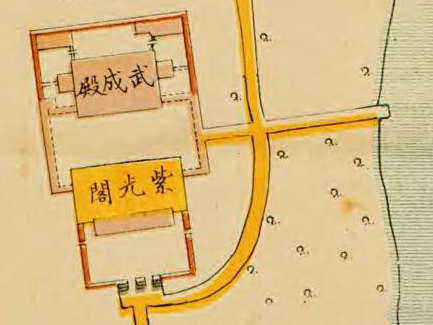

Fig. 11, Hall of Imperial Splendour and the Hall of Military Merits behind it.

Detail, map of the Sanhai (三海 Three Seas), dated 1913, collection of Kyoto University, Japan.

The architectural complex of the Hall of Imperial Splendour consists of two buildings (fig.11): the front Hall of Imperial Splendour has a large terrace from which the Chinese emperors reviewed military exercises. Behind and connected by arcades is the Hall of Military Merits (Wucheng Dian 武成殿).

The Qianlong emperor commissioned paintings of a total of sixteen monumental battle scenes (each approx. 4 x 8 meters, see as an example: fig. 12) and one hundred officers’ (known as Bannerman) portraits (see as an example: fig. 13) to commemorate the East Turkistan campaign of 1755-1759, whose victorious end was celebrated in the Hall of Imperial Splendour in 1761. In addition, there were some one hundred and thirty oil paintings (approx. 72 x 56 cm), approximately thirty handscrolls with paintings of officers and battle scenes (approx. 30 x 200 cm) and sixteen copperplates (approx. 57 x 94 cm), the last made in Paris in the years 1767-1774 and replicating the sixteen monumental paintings of the conquest.10

Documenting his later campaigns, the Qianlong emperor ordered a further approximately twenty monumental battle scenes and one hundred and eighty Bannerman portraits to be painted. In addition, there were one hundred and eighty oil paintings, approximately six hand scrolls with officer images, and a further sixty-two copperplates and thirty-two red lacquer panels carved with battle scenes. These works of art were mainly kept in the rear Hall of Military Merits.11

Fig. 12: Fragment of the wall painting The Battle of Qurman (left-hand side), Qianlong reign, 1760, wall painting, ink and colour on silk, height 68.6 cm, width 105.5 cm

Private collection.

When the foreign soldiers entered the Hall of Imperial Splendour in 1900, it had been redecorated just ten years earlier, in 1890. In the middle of the nineteenth century, a wave of uprisings in China had flared up, which the imperial army was able to quell only with great effort. The Guangxu emperor (r. 1875-1908) remembered the tradition of the Qianlong reign and ordered the creation of seventy-three large-format battle paintings (approx. 134 x 300 cm) together with separate written texts of the same size. In addition, the Guangxu emperor had some fifty officer portraits painted.

For the new display, the paintings from the Qianlong reign were taken down and most likely stored somewhere in the building complex. Twelve paintings of the later Guangxu battle series (the suppression of a Muslim rebellion in the south-west together with their descriptive texts) were apparently not in the Hall of Imperial Splendour in 1900-1901, as they are still in the Palace Museum in Beijing today.

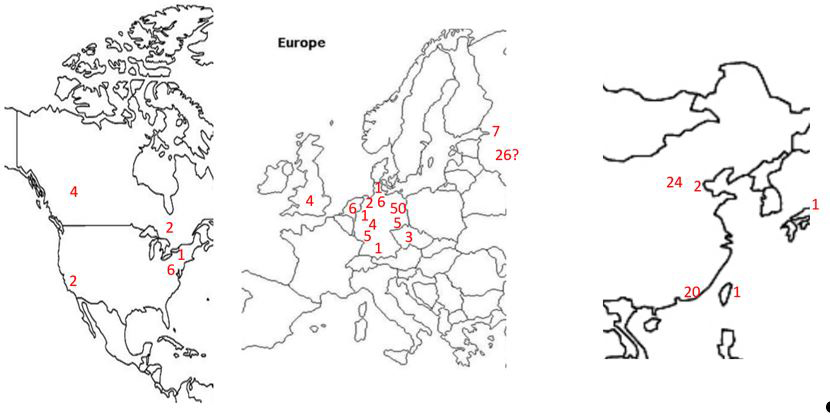

Today, only about one-quarter of these works of art can still be proven to exist (see overview in fig. 14). Of the monumental battle paintings of the Qianlong period, for example, only one remains completely intact, otherwise only a few fragments remain. Both the complete painting and the painting fragments are located in Germany.12 Other art works are to be found, mainly in Germany, some of them recognized only recently.13

Fig. 13: Bannerman painting of Daktana, hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk, height ca. 185 cm, width 95 cm

Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, OAS 1991-3c.

The chart below provides only an approximate indication of the numbers of works in question. With some pictorial series it is not known exactly how many images were originally painted. In addition, numerous battle paintings and handscrolls were cut up and are today counted as several works due to the existence of various fragments. It is also unclear how many Bannerman paintings were in Berlin originally, whether some were destroyed in the Second World War, or how many are today held in Russia. Even if some of the numbers in fig. 14 were to change, the chart shows that considerable destruction of art from the Hall of Imperial Splendour took place during the Boxer Rebellion.

The vast majority of extant works of art from the Hall of Imperial Splendour are or were held in German museum collections. The Ethnological Museum of Berlin was one of the first institutions to house these works, especially in the case of the Chinese officers’ paintings. Many soldiers returning from China offered to sell the museum such pictures in the years after 1901. Müller, who had bought two of the paintings in Beijing, was thus able to expand the museum collection to thirty-two Bannerman paintings (each bought for around 120 marks) and approximately ten oil paintings (bought for around 10 marks each).14

|

Formats and Subjects |

created (approx.) |

extant (approx.) |

|

Battle paintings |

100 |

31 |

|

Paintings of Officers |

600 |

100 |

|

Handscrolls |

36 |

10 |

|

Copperplates |

88 |

37 |

|

Lacquer panels |

32 |

16 |

|

Totals |

865 |

194 |

|

Fig. 14: Comparison of the original and the still extant works of art from the Hall of Imperial Splendour (overview compiled by the author). |

||

Some of these Bannerman paintings were taken to Russia after the Second World War and are today stored in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.15 Further Bannerman paintings are in museums in Dresden, Munich, Heidelberg, Cologne, Mannheim, Schleswig, Bremen, and Hamburg. After the Second World War, a number of these paintings were acquired at auction for Canadian collections in Edmonton and Toronto. Two Chinese private collectors in New York (Dame Dora Wong) and in Hong Kong (Mr. Ronald Chow) acquired many of these paintings in recent decades.16

A German soldier fighting the Boxer Rebellion, Sergeant Wuensch, from the 3rd Company in the 1st Sea Battalion, brought home from China an unusually large collection consisting of a Bannerman portrait and twenty-three oil paintings. These paintings appeared on the art market in the 1970s and then again in the 2010s and are now scattered around the world in various collections. This is one of the few cases in which looted officer paintings can be specifically linked to a particular soldier.

Only one of the monumental battle paintings has remained completely intact, that of the Taiwan campaign 1787-1788, which is now in Hamburg’s Ethnological Museum, the MARKK,17 (inventory number A4578, acquired 1902). Also in Germany are four known fragments of battle paintings (both in museums – in Hamburg and Heidelberg – and private collections): three from the East Turkestan depiction of the Battle of Qurman from 1760 and one from the painting of the Nepal campaign of 1792.18

Of the eighty-eight copperplates used to print the engravings that illustrate battle scenes, thirty-four plates are today in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. Müller described in his travel report that Anton Goebel, valet of the German envoy Mumm von Schwarzenstein (1859-1924), owned a large number of these copperplates in Peking in 1901 and demanded “fantasy prices” for them.19 Another plate is today in Beijing;20 two other plates were acquired at auction by the British Museum, London, and the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 15: Approximate overview of the whereabouts of the works of art from the Hall of Imperial Splendour (overview compiled by the author).

The purchase by the Houghton Library was made on 7 May 1952 through the Ader/Rheims auction house in Paris (lot 105). This sale was attended by the French art dealer Michel Beurdeley (1911-2012), who, in 1967, offered a brief insight into the provenance of these works of art:

After the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, the imperial apartments were looted by Austrian soldiers stationed in the city. Among the plunder seized were the famous engravings. Resold to a famous collector, Mr. R [Rothschild?], the series passed, with my assistance, through a public sale at the Hôtel Drouot in 1952, with a copper plate engraved by J.-P. Le Bas depicting the Battle of Khorgos.21

Six of the red lacquer panels were privately owned by the German Emperor and were brought to Huis Doorn in the Netherlands in 1919.22 One red lacquer panel is in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Asian Art Museum) in Berlin, others were scattered around the world through sales in various locations.

Of the sixty-one looted battle paintings of the later Guangxu series from about 1885, eleven are still preserved today. Four of them are in the Mactaggart Collection in Edmonton, Alberta, purchased from auctions in the past decades. Another seven paintings are located in England and Prague (two each) and one each in Hildesheim, New York (Dame Dora Wong) and Hong Kong (Mr. Ronald Chow). The files of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin mention another of these paintings, given to the museum on loan by Colonel Staff Doctor Hildebrandt in 1902 (no. 15 of the Nian series Capturing the Nian leader Lai Wenguang), but it has been missing since the Second World War and may be in Russia.23

In all, more than one hundred works of art with an imperial provenance from the Hall of Imperial Splendour have found their way onto the art market since the Boxer Rebellion, many of them even multiple times. In the auction catalogues, their provenance is regularly highlighted and the looting in Beijing during the Boxer Rebellion is referenced.24 Most of these are now in Western museum collections.

For several years now, museums have been critically questioning the provenance history of their collections. The origin of the paintings from the Hall of Imperial Splendour is easy to discern because of their unmistakable character. Systematic efforts on the part of the Chinese to locate these works of art do not seem to have been made to date. However, a recent article in the Forbidden City Journal (紫禁城) by Nie Chongzheng refers to the glorious past, of which these paintings are a reminder.25

It is hoped that at least the two large collections of officer paintings now in Chinese hands will one day be made accessible to the Chinese public. The ideal place for this would of course be the Hall of Imperial Splendour itself, which unfortunately is currently not open to the public, as it is part of the Zhongnan Hai government district.

Niklas Leverenz is an independent scholar based in Hamburg, specializing in research on Qing-dynasty Chinese battle paintings.

1 See Paul Cohen, History in three keys: the boxers as event, experience and myth (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997); and Diana Preston, Besieged in Peking (London: Constable, 1999).

2 On the lootings see James L. Hevia , Looting and its Discontents, in Robert Bickers, The Boxers, China and the World (Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, 2007) and Till Spurny, Die Plünderung von Kulturgütern in Peking 1900/01 (Berlin: Wissenschatlicher Verlag, 2008).

3 Alfred Graf von Waldersee, Die Eroberung und Plünderung Pekings im August 1900, in Preußische Jahrbücher 1923, 283-293; English translation, Count Alfred Waldersee, Plundering Peking, in The Living Age, 317:4118 (1923), 563-569; see 566.

4 Fedor von Rauch, Mit Graf Waldersee in China: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen (Berlin: Fontane, 1907), 120; see also Adolph Obst, Theodor Rocholl, Deutschland in China 1900-1901: Bearbeitet von Teilnehmern der Expedition... (Düsseldorf, Druck August Bagel, 1902), 143.

5 Obst, Rocholl, Deutschland in China, 153

6 Müller report, 15. For the English translation see Leverenz, From Berlin to Beijing, 467.

7 Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Sammlung Ost- und Nordasien: Ident. Nr. I D 25376, colours on silk, 5.43 x 10.15 meters. On the painting, see Ching-Ling Wang, Praying for Myriad Virtues: On Ding Guanpeng’s ‘The Buddha Preaching’ in the Berlin Collection (Dortmund: Kettler, 2017); esp. 126.

8 Müller report, 17. For the English translation see Leverenz, From Berlin to Beijing, 469.

9 Di Baoxian 狄寶賢 (1873-?), Pingdeng ge biji 平等閣筆記 (China: s.n., 1922), 3b.

10 An overview of all artifacts and additional literature can be found on the website www.battle-of-qurman.com.cn (accessed 13 September 2020).

11 Walter Fuchs, Die Entwürfe der Schlachtenkupfer der Kienlung- und Taokuang-Zeit, in: Monumenta Serica 9 (1944), 101–22.

12 See Niklas Leverenz, A Third Fragment of The Battle of Qurman, in Orientations, May 2015, 76-80.

13 See Niklas Leverenz, A Set of Eight Gurkha Campaign Copperplate Prints, in Getty Research Journal, Volume 11 (2019), 185–196.

14 See Archive of the Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, File no. I B 037 Asien (the file containing the Müller report).

15 See: Annette Bügener, Die Heldengalerie des Qianlong-Kaisers (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2015), 24.

16 Personal communications to the author.

17 The name is the abbreviation for the Museum am Rothenbaum – Kulturen und Künste der Welt.

18 See footnotes 13 and 14. Two fragments of the East Turkestan painting will for the first time be exhibited next to each other in the MARKK Museum, Hamburg, starting December 2020.

19 Müller report, here: content of Crate #99. For the English translation see Leverenz, From Berlin to Beijing, 476-477.

20 Prof. Chen Shou-yi, formerly Honolulu University, writes in an article from 1939 that several of these copper plates were found in Beijing in 1932, but nothing more is known about them, see News Bulletin of the Honolulu Academy of Arts, December 1939, 1-2.

21 The original French text reads : “Après la révolte des Boxers, en 1900, les appartements impériaux furent pillés par les soldats autrichiens cantonnés dans la ville. Dans le butin saisi, figuraient les fameuses gravures. Revendues à un célèbre collectionneur, M. R..., la série passa, par mes soins, en vente publique à l’hôtel Drouot, en 1952.” Quoted from Michel Beurdeley, Gravées en France, Les Conquêtes de l’Empereur de Chine, in: Plaisir de France, Mai 1967, 30-35.

22 Herbert Butz, Bilder für die Halle des Purpurglanzes (Berlin: Fröhlich und Kaufmann, 2003), 62.

23 Archive of the Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, File no. I B 037 Asien, which also includes the Müller report.

24 See for example Sotheby’s Auction Catalogue Yuan Ming Yuan, Imperial Peking and The Last Days, Hong Kong, 9 October 2007.

25 Nie Chongzheng, The reappearance of glory and splendor. The huge battle paintings in the Ziguangge, in Forbidden City Journal, May 2018, 114-138.