ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Lucie Chopard

This study focuses on the relationship between Ernest Grandidier and the art dealers who helped him to build the most important collection of Chinese ceramics in France. The history of this incredible collection – today considered as the largest one of Chinese ceramics in France and kept at the Guimet museum in Paris - is relatively unknown. Often underestimated by the Louvre administration during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Grandidier collection continues to be absent from the major studies dedicated to the history of the Louvre museum. From 1894 to 1912, Grandidier was the sole keeper of his collection and the only one to preside over his collection’s display and acquisitions. The collection archives contain two notebooks in which Grandidier recorded details for each piece in his collection. The Grandidier collection helps to define the Parisian art market and its actors by providing an ensemble of over 6,000 pieces, gathered between the late 1860s and 1912. Leaving apart the question of the collector’s taste, the close study of the purchases helps us to identify new dealers, enhances our understanding of others and provides the quantity and typology of the pieces they supply. Progress in the field of the study of the Parisian art market will provide more data and allow for a better comprehension of the complex interaction between scholars, collectors, art dealers and museums which facilitated a meeting between the French cultural milieu and Asian art in the second half of the nineteenth century.

Nowadays, research on Asian collections in France during the nineteenth century focuses on the major figures of Henri Cernuschi (1821-1896) and Emile Guimet (1836-1918), who founded their own Parisian museums, now devoted to Asian art.1 At the end of the nineteenth century, other collections of East Asian art were displayed in Paris: private collections, such as Edmond de Goncourt’s2 (1822-1896), as well as public ones3 such as the Louvre. Regarded as the preeminent French museum, the Louvre officially started to collect Asian art in 1893.4 In the process, an important group of Chinese porcelain was donated to the French State: the collection of Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912). Born and raised in a wealthy Parisian family, he had started to collect Chinese porcelain in the 1860s and continued to accumulate pieces until his death in 1912.

The history of this incredible collection – today considered as the largest one of Chinese ceramics in France and kept at the Guimet museum in Paris - is relatively unknown.5 Often underestimated by the Louvre administration during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Grandidier collection continues to be absent from the major studies dedicated to the history of the Louvre museum.6 Moreover, the study of the history of collecting Chinese ceramics in Paris during the second half of the nineteenth century has been affected by the predominance of Japonism in France, which favours the study of the history of collections of Japanese works of art.7 In this slightly biased context, the study of the provenance of the items collected by Ernest Grandidier, more than 6,000 pieces, deserves a meticulous investigation of the collector and his interactions with dealers.8 This field of research involves reflection about the location, the date, the people and the mechanisms involved in the acquisitions, highlighting links between the Parisian art market and the Louvre. It is a good example of the “entangled histories of museums and art markets” noted by Bénédicte Savoy and Charlotte Guichard.9

Ernest Grandidier started collecting during the late 1860s, first taking an interest in books, then gradually moving on to Japanese ceramics and Chinese porcelain.10 He gave up collecting Japanese ceramics in 1899, instead concentrating his interest on Chinese objects which represent the biggest part of the collections.11 This paper focuses precisely on this latter collection: consisting primarily of porcelain from the Qing dynasty (1644-1912), together with a few examples from the Ming (1368-1644), Yuan (1279-1368) and Song (960-1279) dynasties (fig. 1). Some of them are now recognized as masterpieces,12 while others are of lesser quality.

|

Identification of the pieces according to Grandidier (1912) |

Number of acquisitions (nb. of inventory numbers) |

|

China, Qing, Kangxi |

1776 |

|

China, Qing, Yongzheng |

459 |

|

China, Qing, Qianlong |

1839 |

|

China, Qing, Jiaqing |

79 |

|

China, Qing, Daoguang |

127 |

|

China, Qing, other periods |

8 |

|

China, Ming |

493 |

|

China, Yuan |

8 |

|

China, Song or Yuan |

16 |

|

China, Song |

84 |

|

China, Han |

1 |

|

China, unknown |

29 |

|

Japan |

698 |

|

Unknown |

172 |

|

Other provenance |

4 |

|

Total |

5,793 |

|

Fig.1: Chart presenting the repartition of the pieces of the collection depending on designations given by Ernest Grandidier (1912) ©Lucie Chopard |

|

In 1894, Grandidier donated his entire collection of Chinese porcelain to the Louvre.13 The sheer volume of items, over three thousand pieces, made the donation a considerable enrichment of the decorative arts collection. Furthermore, the original conditions for the donation were noteworthy: first, the collector required that the museum allocate a sum of 6,000 francs per annum in order to enhance the collection bearing his name; second, that he be appointed keeper, and third, that he be granted independent status within the Department of Decorative Arts at the Louvre. The Grandidier collection became a part of this department “par sa nature” (due to its nature). Thus, the newly appointed keeper Grandidier should have been subordinate to the Chief Keeper of the Department. Instead, through demanding independent status, Grandidier reported directly to the Director of the museum.

Before the collection’s arrival, only a few Chinese objects were to be found within the museum: there were disparate collections, such as enamels, ceramics and Chinese objects preserved in the ethnographic museum of “Musée de Marine du Louvre”14 and scattered objects such as Chinese ceramics from the Thiers collection.15

Against this background, the choice of donating the largest collection of Chinese ceramics in France to the Musée du Louvre may be surprising. However, in 1894, no French museum was specifically dedicated to Asian art16 and the Louvre presented a symbol of significant social recognition for the collector. In a report dated 1893 to the Director of the Museum, Albert Kaempfen (1826-1907), one of the Louvre’s keepers, Emile Molinier (1857-1906), summarized the reasons which, in his opinion, justified the acceptance of the donation of the Grandidier collection. According to him, the collection was “a complete ensemble”, presenting chronological, formal and decorative diversity. It was also worthy of being displayed in the museum: the pieces were ancient, the shapes pleasant and the decoration rich and well-preserved. Moreover, the collection was famous and included similar objects to those of the South Kensington Museum in London and the collection at the Dresden museum17 – the last one a key reference to the intense rivalry and circulation of ideals between European museums at the time.18 Molinier’s final argument underlines the importance attributed to the Grandidier collection as a source of models to be used by French artists and industries:19 this was also the view of the collector. At the time, the debate about decorative arts and the search for renewal through ancient objects had become slightly outdated, but still continued here.20

From 1894 to 1912, Grandidier was the sole keeper of his collection and the only one to preside over his collection’s display and acquisitions. The accounts of the meetings of the Louvre’s advisory committee21 reflect limited discussion on acquisitions and a typically unanimously favourable opinion: no one seems to have contested – or to have dared to contest - the choices of the keeper who still regularly donated Chinese porcelain to the museum until his death.

The collection’s archives contain two notebooks22 in which Grandidier recorded details for each piece in his collection. The documents are structured in four columns, where the collector reported the inventory number of the object, its summary designation, its source, and its purchase price or, if applicable, its assumed value. However, this source should be approached with caution: Grandidier sometimes gives approximate prices and does not always indicate the precise source of the objects. Pending further clarification to be provided later in my research, and given that according to my initial surveys, most of the information in the notebooks is accurate, I have relied on them to provide an overview of the origin of the Chinese porcelain pieces in the collection.

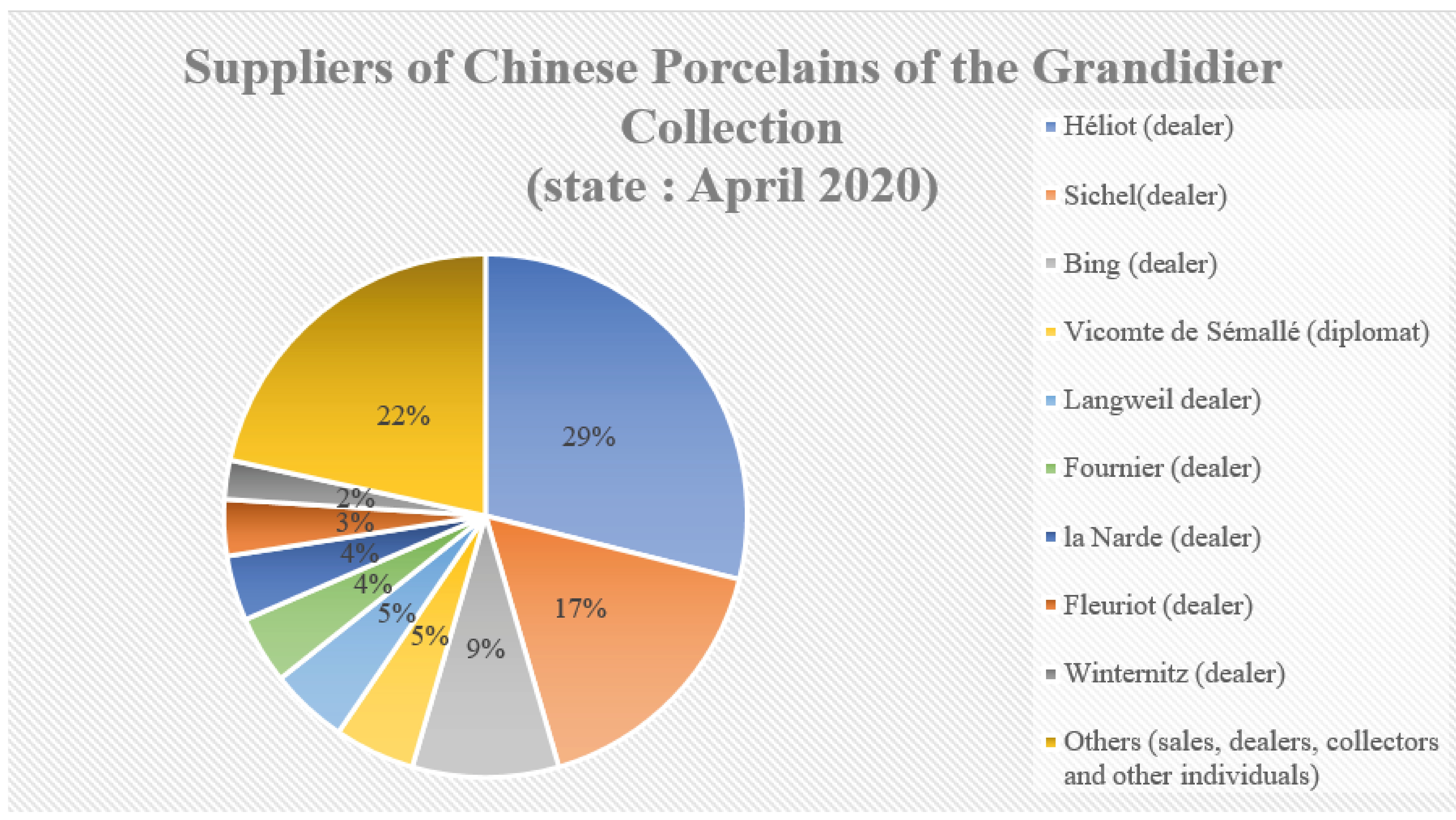

Based on the archives, we can see that the acquisitions came from various sources in terms of both Chinese and Japanese collections: public auctions, purchases from dealers, or donations. After the collection was placed in the Louvre, Grandidier also recovered pieces already present in the museum’s collection and installed them in his showcases, and he received various donations. Regarding the entire collection, the majority of the pieces appear to have been purchased from “dealers” (fig. 2).23 This category covers anybody claiming to be trading in antiques and/or owning a shop in Paris – the notebooks only mention family names with no further information concerning the terms of the purchase, except for prices. The identification of those dealers and of the art sales suggest that Grandidier primarily acquired porcelain pieces in Paris. Only three purchases occurred elsewhere, in Brussels, and not a single one in London.

Fig.2: Chart presenting the repartition of the pieces of the collection depending on suppliers indicated in the collector’s notebooks ©Lucie Chopard

In regard to the date of the acquisitions, the problem is still complex today: at first glance, it may be assumed that acquisitions were recorded in the notebooks as they were made. However, by comparing the information in the archives with the records in these two documents, it appears that the first part of the notebooks was filled in retrospectively, and that it was only after that Grandidier started to record his acquisitions in a more systematic way.24 However, it is still possible to date many purchases and donations more or less accurately by using the dates of public auctions and the life dates of the people involved. It is also possible to reconstruct the content of the first donation of 1894, which is still a work in progress. On the basis of current knowledge, it appears that Grandidier purchased the pieces corresponding to the first four thousand inventory numbers of the collection between the end of the 1860s and 1894, and the remaining two thousand between 1894 and 1911.

Studies of the Parisian art market are still rare, especially in the domain of works of art.25 Regarding the market for Chinese artefacts, studies usually deal with “Asian art” in general and approach Japanese and Chinese objects together,26 with only few publications focusing on Chinese objects.27 A significant part of what is known today comes from such valuable sources as the Goncourt Journal28 or the memoirs of Raymond Koechlin.29 The study of art catalogues and auction archives contrasts with the importance attributed to some actors by Goncourt and Koechlin whose publications remain subjective. From all these studies some “big names” in the field emerge such as Bing, Goncourt, Desoye, etc, but hardly ever famous works of art. The Grandidier collection helps to define this market and its actors by providing an intact ensemble of over 6,000 pieces gathered between the late 1860s and 1912. Leaving apart the question of the collector’s taste, a close study of the purchases helps us to identify new dealers, enhances our understanding of others and provides the quantity and typology of the pieces they supplied.

Among the identified dealers in Chinese ceramics,30 a majority was not specialized in Chinese or Asian art. They were mainly French, some of them Dutch selling antiques in Paris, like Sarluis who was based in The Hague. Only one Chinese dealer was identified: Tien-Pao, whom Goncourt frequented and mentioned in his Journal.31 Grandidier’s acquisitions involved two generations of dealers: one centred on the Sichel brothers, Laurent Héliot and Siegfried Bing, and another, later, dominated by Florine Langweil. This shift seems to have taken place in the 1890s, and it coincided with a spectacular rise of prices for Chinese porcelains. This observation appears to be compatible with Koechlin’s description of a “new wave” of dealers going along with the taste for ancient Chinese ceramics in the early twentieth-century.32

Three dealers were Grandidier’s main suppliers: Laurent Héliot (1848-1909), later entering into partnership with his son Gaston Héliot33 (1879-1936), who supplied almost a third of his collection of Chinese porcelain34 (28,9% of inventory numbers), the Sichel brothers (Auguste, Philippe and Otto) with 16,5% and Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) with 9% (fig. 2). The other main dealer regarding the Grandidier collections was Antoine de la Narde (1839-19?) who provided fewer Chinese porcelain pieces than the three others but much of the Japanese ceramics.35 Laurent and Gaston Héliot, the Sichel brothers and Bing alone represent in total more than half of Ernest Grandidier’s acquisitions of Chinese porcelain between 1870 and 1912. The volume of goods and of money involved is impressive, with more than 990,000 francs paid by the collector to these three dealers. Next are the Viscount Robert de Semallé (1849-1936), formerly stationed in China, whose contribution to the Grandidier collection is mainly represented by an impressive set of snuff bottles that explains the huge number of these items in the collection, and a dealer, Florine Langweil36 (1861-1958), with 5% of the collection each. Among the remaining suppliers we can mention “Fournier”, the name of a dynasty of Parisian dealers37 with 4,2% of the collection, Antoine de la Narde with 4%, Mrs. Fleuriot with 3,5% and S. Winternitz, with 2,4%. The other suppliers are much less important, each of them providing less than 2% of the collection and a total 25,5% of the entire collection.

This distribution highlights the importance of Héliot, a dominant dealer of the period who is not very well studied, and of the Sichel brothers, whose family name is cited most often in connection with Philippe’s trip to Japan in 1874 and the account of his journey.38 Similarly, Bing is more often mentioned in the context of his leading role in Japonism’s dissemination than for his role in purchases of Chinese art.

The identification of the objects in the Grandidier collection which passed through each of the three major dealers (Héliot, Sichel, Bing) helps to better understand the focus of their dealing activities. In addition to their civil status, their addresses, and their description found in the pages of the Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce Didot-Bottin,39 part of their stock forms a valuable source of information on their work, by revealing their participation in the flourishing Chinese art trade on the Parisian market and providing more information on the availability of specific pieces.

Laurent Héliot seems to have started his commercial activities in Paris in the 1870s. Over the course of his life, his trade takes place from 62, rue de Clichy, and later at 34, rue de Berlin. The letterhead of his invoices always mentions a specialization in Chinese art, especially Chinese porcelain. He died in 1909 after more than forty years in the trade.40 His contribution to the Grandidier collection of Chinese porcelain comprises 1,490 purchases and two gifts. These transactions took place until 1911: in all probability, his sons carried on their father’s trade after his death.41

Auguste (1838-1886), Philippe (?-1899), and Otto (1846-1891) Sichel were three brothers from Germany who started their commercial activities in Paris in the 1870s. Their professional links are not well known: it is possible that they had already worked together for some time.42 On the basis of the available documents, it is difficult to separate the purchases Grandidier made from each of the Sichel brothers, because of his habits of only mentioning family names. In all likelihood he bought pieces from all three brothers: he purchased some pieces during the auction of Auguste’s collection in March 188643 and continued to buy after Auguste’s death, indicating a trading relationship with the two remaining brothers. Well-known and studied for their trade in Asian art,44 they also dealt in European works of art.45 Grandidier bought pieces from Philippe Sichel until 1898.

Siegfried Bing is the best-known of these three dealers. A strong promoter of Japonism and Art nouveau46, his activities took place in various Paris locations and on the other side of the Atlantic. Grandidier bought more Chinese than Japanese ceramics from him until 1902.

Comparing the pieces purchased from each of these three dealers (fig. 3) and bearing in mind the global distribution of the pieces of the collection,47 it comes as no surprise that the objects the three of them sold to Grandidier were considered to be from the Kangxi (1661-1722) and the Qianlong periods (1735-1796).

|

Identification of the pieces according to Grandidier (1912) |

Acquisitions from Héliot (no. of inventory numbers) |

Acquisitions from Sichel (no. of inventory numbers) |

Acquisitions from Bing (no. of inventory numbers) |

|

China, Qing, Kangxi |

602 |

331 |

131 |

|

China, Qing, Yongzheng |

135 |

85 |

65 |

|

China, Qing, Qianlong |

405 |

292 |

185 |

|

China, Qing, Jiaqing |

15 |

9 |

14 |

|

China, Qing, Daoguang |

12 |

28 |

13 |

|

China, Qing, Xianfeng |

0 |

0 |

2 |

|

China, Qing, Tongzhi |

0 |

3 |

0 |

|

China, Ming |

200 |

51 |

26 |

|

China, Yuan |

6 |

0 |

1 |

|

China, Song or Yuan |

3 |

4 |

3 |

|

China, Song |

41 |

10 |

5 |

|

China, unknown |

5 |

3 |

4 |

|

Japan |

34 |

28 |

129 |

|

Unknown |

33 |

19 |

63 |

|

Other provenance |

1 (Siam) |

0 |

1 (Annam?) |

|

Total of procurements |

1491 |

863 |

642 |

|

Fig. 3: Chart presenting the purchases of Chinese porcelains by Héliot, Sichel and Bing, according to the pieces’ dating given by the collector ©Lucie Chopard |

|||

They also sold porcelain of the Yongzheng (1722-1735), Jiaqing (1796-1820) and Daoguang (1820-1850) periods. Five items stand out in curious isolation: two pieces of ceramics from the Xianfeng period (1850-1861) from Bing (fig. 4 and 5) and three from the Tonghzi period (1861-1875) bought from the Sichel brothers (fig. 6, 7 and 8). Few pieces from these periods are part of the collection: Grandidier considered the production of those reigns to be of poor artistic value.48

Fig. 4: Bowl, China, kilns of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi)

Qing dynasty, Xianfeng period (1851-1861), porcelain, 5,5 x 12,6 cm, mark “Da Qing Xianfeng nian zhi”

Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, inv. G1774 ©Lucie Chopard

Chinese ceramics from the nineteenth century may have been attributed to the eighteenth century49 because of the taste of the period which may have pushed some dealers to backdate their items in order to increase their attractiveness – and their prices - or because of a lack of expertise. Regarding the five abovementioned ceramics that were bought from the Sichel brothers, there was no doubt about their date at the time of purchase because they have a reign mark on their base.50 Héliot seems to have sold a few more pieces from the Ming dynasty than the others: he supplied more than 40% of the Ming pieces in the collection. Few pieces are dated from the Song and Yuan dynasties: the productions of this period were of little interest to Grandidier. Nevertheless, he collected a small number of them, most likely to reflect the general history of Chinese porcelain in his collection.51

Fig. 5: Vase, China, kilns of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi), Qing dynasty, Xianfeng period (1851-1861), porcelain, 31 x 18 cm, mark “Da Qing Xianfeng nian zhi”

Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, inv. G1988 ©Lucie Chopard

The three dealers sold ceramics of high and low quality, but most of the highlights in the collection came from Héliot and the Sichel brothers. For example, two porcelain pieces regarded as masterpieces at the time and reproduced by heliogravure in the collector’s publication of 1894 came from their business: the delicate Guanyin figure in monochrome white52 from the Dehua kilns in Fujian (fig. 9) was bought from the Sichel brothers and the ten thousand flowers vase53 which had escaped from Grandidier’s clutches at the Camondo auction54 was bought the same year from Héliot. The Sichel brothers distinguished themselves by providing a higher percentage of high-quality pieces with regard to their total number of items. The difference in the quality of the porcelain traded by these dealers may possibly be due to their sources of supply, to their knowledge or to their “eye”, considered as the ability to identify a masterpiece amongst an assemblage of good pieces.55 In the case of Sichel, Bing and Héliot, the lack of personal and business archives preserving precise information prevents a detailed study of their sources of supply. We know that Siegfried Bing was buying in Asia,56 and at least two of the Sichel brothers had been in Japan,57 a country where Chinese porcelain circulated and where collecting Chinese ceramics has a long tradition. They also bought at auction, a well-known practice of art dealers of the time.58

Social relationships and business networks played an important role in the Paris art market by connecting individual actors and Parisian museums. At the centre of this network, the relationship between the collector and the dealer was one of the key market and social drivers. While these relations were cordial, and sometimes friendly, it should not be forgotten that they took place over a long period of time and were able to evolve: the minutes of the auctioneers, consulted over several decades, clearly show us that all these market players interacted for sometimes over thirty years.59 In his Journal, Goncourt had already noted the evolution of dealers from merchants of “bric-à-brac” to “gentlemen dressed by our tailors”, using Auguste Sichel as an example.60 The proximity between collector and dealer is evident in an anecdote reported by Alfred Grandidier in his Mémoires where he explains that his brother invited Philippe Sichel to his castle near Paris, the Château de Fleury-Mérogis, and that the dealer used the opportunity to convince him to sell the estate in order to buy more porcelain for his collection.

Fig. 6: Bowl, China, kilns of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi), Qing dynasty, Tongzhi period (1862-1874), porcelain, 6,5 x 10,5, mark “Da Qing Tongzhi nian zhi”

Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, inv. G1141 ©Lucie Chopard

Whether entirely accurate or not, this anecdote reveals that Philippe Sichel remained in Alfred’s memory as an important supplier and maintained a close relationship with his brother. It was also Philippe Sichel to whom Grandidier turned in 1894 when his collection was donated to the Louvre. Two experts were mandated to value the Grandidier collection and to decide its financial worth. The collector chose Sichel,61 while the Louvre Museum invited Siegfried Bing to appraise the collection.62 As these two experts were also Grandidier’s main suppliers, the situation appears somewhat ethically questionable from a modern perspective.

Auctioneer’s minutes also highlights the role of dealers as intermediaries. Grandidier was strangely absent from some major sales, yet he reported in his notebooks purchases made at sales he did not attend, for example the Goncourt sale on March 1897.63 The number of such cases raises questions about the role of dealers as intermediaries, in the light of the previous considerations about their relationship with the collector. Merchants may be commissioned to buy some items on behalf of a client during a sale. A close study of the hammer price and the one paid by the collector should reveal more information about the commission received by the dealer for his services and yield further clues about the relationship between Grandidier and his dealers. This type of research may provide us with new insights into scholarly knowledge of Chinese porcelain at the end of the nineteenth century. The earliest studies of these items in France took place during the second half of the century, with an important involvement by collectors in the process.64 The close links between Grandidier and his dealers, as demonstrated by the number of items bought and the large sums of money that were paid, are likely to have played a significant role in the development of his scholarly knowledge of Chinese porcelain.

Fig. 7: Bowl, China, kilns of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi), Qing dynasty, Tongzhi period (1861-1875), porcelain, 6 x 13,5 cm, mark “Da Qing Tongzhi nian zhi”

Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques - Guimet, inv. G1343 ©Lucie Chopard

Fig. 8: Bowl, China, kilns of Jingdezhen (Jiangxi). Qing dynasty, Tongzhi period (1861-1875), 6,5 x 12,5 cm, mark “Tongzhi nian zhi”. Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques - Guimet, inv. G1405 ©Lucie Chopard

Fig. 9: Statuette of Guanyin, China, kilns of Dehua (Fujian)

Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662-1722), XVIIth century, porcelain, 31 x 18 cm, seal “He Chaozong”

Paris, musée des Arts asiatiques – Guimet, inv. G535

©Lucie Chopard

As keeper of his collection at the Louvre, and benefiting from his reputation and independent status, Grandidier brought the Paris market for Chinese porcelain and the museum closer together. He seemed to trust only a few dealers and bought new porcelain pieces on a regular basis. While Chinese porcelain entered the Louvre, the choice of objects was made first by the dealers, then by the collector-cum-keeper. This study focuses on the relationship between Ernest Grandidier and the art dealers who helped him to build the most important collection of Chinese ceramics in France. By bringing together the dealers and their objects, we can gain new understandings about their trade and abilities. As such, the Grandidier collection is a real trove of knowledge which can be used to further our study of the Parisian and French art market of the time: Grandidier collected a wide range of ceramics from the early Song and Yuan dynasties to the contemporary period, in various forms and styles of decoration. This approach complements the study of the auction procès-verbaux which does not address the question of intermediaries between the collector and the art object. It also partially overcomes the lack of surviving private archives for most of the dealers. Progress in the field of Paris art market studies will provide more data and allow for a better comprehension of the complex interaction between scholars, collectors, art dealers and museums which facilitated the convergence between the French cultural milieu and Asian art in the second half of the nineteenth century. While this article takes a monographic approach, due to the few available studies devoted to the subject, comparative approaches already promise to be fruitful.

Lucie Chopard is a PhD student at the laboratoire Saprat - EA 4116, Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes - PSL, Paris.

1 For the current status, see Ting Chang, Travel, collecting, and museums of Asian art in the nineteenth-century (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013); Ting Chang, Emile Guimet’s Network for Research and Collecting Asian Art (ca. 1877-1918), in Charlotte Guichard, Christine Howald and Bénédicte Savoy, eds., Acquiring cultures. Histories of World Art on Western Markets (Boston, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018), 209-222; and Silvia Davoli, Comparing East and West: Enrico Cernuschi’s Collections of Art Reconsidered, in Susan Bracken, Andrea M. Gáldy and Adriana Turpin, eds., Collecting East and West (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016), 41-59.

This paper derives from a conference paper I presented on 7 November 2019 in Berlin as part of the workshop “‘Pillage is formally prohibited...’’ Provenance Research on East Asian Art #3”, organised by the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, the Technische Universität Berlin and the University of Glasgow. I am grateful to Mrs. Deléry, curator at the Musée Guimet, for her assistance with the photographs presented here.

2 See Chang, Travel, collecting and museums, and Dominique Pety, Les Goncourt et la collection: de l’objet d’art à l’art d’écrire (Genève: Droz, 2003).

3 Few studies deal with Asian collections in museums outside of Paris. See Musée national de céramique, Sèvres, L’odyssée de la porcelaine chinoise (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2003); and Pauline D’Abrigeon, La collection extrême-orientale du musée Adrien Dubouché de Limoges, in Cahiers de l’Ecole du Louvre, 6, (2015), 43-52.

4 The collection of East-Asian art created in the Department of Decorative Arts in 1893 mainly consisted, during the first years, of Japanese prints and objects.

5 Jean-François Jarrige, Du Musée du Louvre au Musée Guimet, in Les donateurs du Louvre (Paris: éditions de la RMN, 1989); Xavier Besse, La Chine des porcelaines (Paris: Edition de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 2004); and Wan-Chen Chang, The Chinese Ceramic Collection of Ernest Grandidier, in Marie-Catherine Rey, ed., Paris 1730-1930: A taste for China (Hong Kong: Kangle ji weshua shiwushu, 2008), 110-115.

6 Recently, see: Jacques Giès, Les arts asiatiques au Louvre, in Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Yannick Lintz, Françoise Mardrus and Guillaume Fonkenell, eds., Histoire du Louvre (Paris: Louvre éditions, Fayard, 2016), vol. II, 460-461.

7 For an up-to-date bibliography, see Béatrice Quette, ed., Japon japonismes (Paris: MAD, 2018) and Geneviève Lacambre, A l’aube du japonisme. Premiers contacts entre la France et le Japon au XIXe siècle (Paris: Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris, 2018).

8 As noted in Christine Howald and Alexander Hofmann, Introduction, in Journal for Art Market Studies 3 (2018), 3.

9 Charlotte Guichard and Bénédicte Savoy, Acquiring Cultures and Trading Value in a Global World. An Introduction, in Charlotte Guichard, Christine Howald and Bénédicte Savoy, Acquiring Cultures, 4.

10 For an overview and bibliography, see Lucie Chopard, Ernest Grandidier, in Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d’art asiatique en France 1700-1939, Paris, INHA, forthcoming (online).

11 According to my comparison of the old inventories of the collection (kept at the Musée Guimet) and two notebooks where Grandidier recorded his ceramics (now in the Archives nationales, 20144787/13), I presume the collection consisted of 4,919 inventory numbers for Chinese ceramics and only 698 for Japanese ones. There might actually be more pieces in the collection (no more than ten or twenty), but I have not found concrete evidence of their existence yet and it is known that moving and renumbering was undertaken after the collector’s death. I plan to provide an extensive study of the Japanese acquisitions in my PhD thesis.

12 An online database presents the masterpieces of the collection: https://www.guimet-grandidier.fr/html/4/index/index.htm (accessed on 28 April 2020).

13 Archives nationales (A.N.), 20144787/13.

14 Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, L’art asiatique, «le déballage d’un sac de marin», in Grande Galerie. Le journal du Louvre, 17 (2011), 44 –46.

15 See Collection d’objets d’art de M. Thiers, léguée au Musée du Louvre (Paris, 1884); and Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Yannick Lintz, Françoise Mardrus et Guillaume Fonkenell, eds., Histoire du Louvre (Paris: Louvre éditions et Fayard, 2016), vol. 2, 359-360.

16 The Guimet Museum in Paris (opened in 1889) was dedicated solely to the history of religions. It displays East Asian objects alongside Egyptian and Roman artefacts. The Cernuschi Museum opened in 1898.

17 A. N., 20144787/13, Rapport à Monsieur le Directeur des Musées Nationaux et de l’Ecole du Louvre au sujet de la collection Grandidier, E. Molinier, 21 November 1893: “La collection réunie depuis plus de vingt ans par M. Grandidier se présente comme un tout complet, comme une réunion méthodique à laquelle il y aura bien peu de retouches à faire pour la rendre parfaite. [...] Il est inutile, je crois, Monsieur le Directeur, de m’attarder à faire une longue description d’une collection particulière auprès de laquelle les séries du même genre que renferment le musée de Dresde et le Musée de South Kensington, à Londres, palissent étrangement et paraissent presque insignifiantes”.

18 Pascal Griener, L’histoire des collections, in Revue de l’art, 200 (2018), 70-71.

19 This role of inspiration for contemporary productions, assigned to works of art in general, was very important for Molinier.

20 Rossella Froissart-Pezone, Les collections du musée des Arts décoratifs de Paris: modèles de savoir technique ou objets d’art?, in Chantal Georgel, La jeunesse des musées (Paris: Ed. de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 83.

21 A. N., 20170157/30-37.

22 A. N., 20144787/13.

23 The others were established collectors, diplomats and a missionary returning from China, art auctions and various persons unknown at this stage of my research.

24 This part is described in detail in my PhD thesis.

25 Charlotte Vignon, Duveen Brothers and the Market for Decorative Arts, 1880-1940 (New York: The Frick Collection, 2019); Manuel Charpy, Le théâtre des objets. Espaces privés, culture matérielle et identité bourgeoise, Paris, 1830-1914, PhD thesis, Université François Rabelais de Tours, 2010 (unpublished).

26 Léa Saint-Raymond, Les collections d’art asiatique à Paris (1858-1939): une analyse socio-économique, in Marie Laureillard and Cléa Patin, eds., A la croisée de collections d’art entre Asie et Occident, du XIXe siècle à nos jours (Paris: Hémisphères Editions, 2019), 229-247.

27 Wen-Chen Chang, The Chinese Art Market in Paris in the Nineteenth Century: Beyond Japonism, in Marie-Catherine Rey, ed., Paris 1730-1930: A taste for China , 94-97; Léa Saint-Raymond, La création sémantique de la valeur. Les ventes aux enchères d’objets chinois à Paris (1858-1939), in Michel Espagne and Li Hongtu, eds., Chine France - Europe Asie. Itineraires de concepts (Paris: Editions Rue d’Ulm, 2018), 217-239. Several studies deal with specific topics, such as the circulation and the sales of looted artefacts of the Summer Palace: see Christine Howald and Léa Saint-Raymond, Tracking dispersal: auctions sales from the Yuanmingyuan loot in Paris in the 1860s, in Journal for Art Market Studies, 2 (2018) (DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i2.30).

28 Edmond et Jules (de) Goncourt, Journal des Goncourt: mémoires de la vie littéraire (Paris, R. Laffont, 1989 [1851-1896]).

29 Raymond Koechlin, Souvenir d’un vieil amateur d’art de l’Extrême-Orient (Paris, E. Bertrand, 1930).

30 Identified dealers (research still in progress): Jules Allard, the Beurdeley family, Siegfried Bing, Jules Boasberg, Edouard Chappey, Mrs. Chaumont, P. Derode, [Mr] Dillon, [Mr] Duvauchel, Mrs. Fleuriot, Antoine et Guillaume Fournier, Armand Samson Gompertz, Emile et Mrs Guérin, [Mr] Guilaine, Mrs Hatty, Tadamasa Hayashi, Laurent Héliot, Mr. and Mrs. Langweil, Mr. Lhussier, Mr Louirette, Mr Lowengard, Mr. Malinet, [Mr] Miallet, MM. Monbro, Antoine de la Narde, Nathan Salomon, MM. Samson, Rienhard Sarluis, Jacques Seligmann, Auguste, Philippe and Otto Sichel, A. Slaes, Tien-Pao, Mr and Mrs Wannieck, F. Willems, S. Winternitz.

31 Goncourt, Journal, t. II, 777 and 804.

32 Koechlin, Souvenirs, 62.

33 After the death of Laurent Héliot in 1909, his son continued to sell Chinese porcelain to Grandidier, possibly with his brother. I presume Gaston worked in his father’s business for years before that as he was considered his true successor at the time (see for example “Exposition d’art chinois”, in Excelsior, 9 June 1914, 4).

34 Here I consider gifts and purchases listed in the notebooks because I am aiming to establish which objects were in their possession. I refer to the inventory numbers and not the number of objects since it seems that porcelain sets (such as garniture and pairs) were bought together for the documented ones.

35 Lucie Chopard, Antoine de la Narde, in Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d’art asiatique en France 1700-1939, Paris: INHA, forthcoming (online).

36 Not much is known about this important personality on the Paris art market. For the current state of research, see Elizabeth Emery, La Maison Langweil and Women’s exchange of Asian Art in Fin-de-siècle Paris, in L’Esprit créateur 56/3 (2016), 61-75. Florine Langweil began by working with her husband at the end of the nineteenth century, then continued to work independently after he left her.

37 Catalogue des anciennes porcelaines de Sèvres, de Saxe, de Chine et du Japon, objets d’art et de curiosité composant la collection de feu M. Fournier Père, Vente Hôtel Drouot, 2-6 mars 1885, Me Paul Chevallier commissaire-priseur, M. Charles Mannheim expert.

38 Philippe Sichel, Notes d’un bibeloteur au Japon (Paris, E. Dentu, 1883). See Max Put, Plunder and Pleasure: Japanese art in the West, 1860-1930 (Leiden: Hotei publ., 2000).

39 Annuaire-almanach du commerce, de l’industrie, de la magistrature et de l’administration: ou almanach des 500.000 adresses de Paris, des départements et des pays étrangers: Firmin Didot et Bottin réunis, (Paris: Firmin-Didot frères, 1857-1908).

40 Lucie Chopard, Laurent Héliot, in Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d’art asiatique en France 1700-1939, Paris, INHA, forthcoming (online).

41 The details of this activity are not well known. See Chopard, Laurent Héliot.

42 Lucie Chopard, Auguste, Philippe et Otto Sichel, in Collectionneurs, collecteurs et marchands d’art asiatique en France 1700-1939, Paris, INHA, forthcoming (online).

43 Catalogue des objets d’art et ameublement... appartenant à M. Auguste Sichel, vente Hôtel Drouot, 1-5 mars 1886, Me Paul Chevallier commissaire-priseur, M. Charles Mannheim expert.

44 Put, Plunder and Pleasure.

45 Chopard, Auguste, Philippe et Otto Sichel.

46 Gabriel Weisberg, Edwin Becker and Evelyne Possémé, eds., The origins of l’art nouveau: the Bing empire, (Amsterdam, Paris, Antwerp, Ithaca, N.Y: Van Gogh Museum, Musée des Arts décoratifs, Mercatorfonds, 2004).

47 Here, I consider once again the identification of pieces as proposed during the nineteenth century.

48 Grandidier, La Céramique chinoise, 224.

49 For example, inv. G93 and inv. G273 were dated to the Qianlong period by Grandidier, but are now considered to be productions of the Xianfeng period.

50 The pieces inv. G1774 and inv. G1988 show a Xianfeng mark, G1141, G 1343 and G1405 a Tongzhi mark.

51 Grandidier, La Céramique chinoise, 5.

52 Statuette, inv. G535. Reproduced in Grandidier, La Céramique chinoise, Pl. X.

53 Vase, inv. G3344. Reproduced in Grandidier, La Céramique chinoise, Pl. XXXVI.

54 Résumé du catalogue d’une belle collection..., [vente Camondo], vente Galerie Georges Petit, 1-3 février 1893, Me Paul Chevallier commissaire-priseur, expert M. Eug. Féral, M. Durand-Ruel et M. Charles Manneim, s.l., s.d., and Archives de Paris (A. P.), D48E3/78.

55 For some reflections about the eye of art expert and the current status of connoisseurship, see Charlotte Guichard, Introduction to the special issue of Revue de Synthèse, 132/1, (2011).

56 Vignon, Duveen Brothers.

57 Put, Plunder and Pleasure, 35.

58 Camille Mestdagh, Ameublement et luxe au temps de l’éclectisme : le commerce et l’œuvre des Beurdeley, in Natacha Coquery et Alain Bonnet, eds., Le commerce du luxe – le luxe du commerce. Production, exposition et circulation des objets précieux du Moyen Âge à nos jours (Paris, Mare et Martin, 2015), 278-287.

59 See for example results presented in Léa Saint-Raymond, Les collections d’art asiatique à Paris. Mrs. Doucet, Durlacher, Fournier, etc., were main buyers for years.

60 Goncourt, Journal, vol. 2., 650-651.

61 A. N., 20144787/13.

62 A. N., 20144787/13.

63 Objets d’art japonais et chinois, peintures, estampes, composant la collection des Goncourt, vente Hôtel Drouot, 8-13 mars 1897, commissaire-priseur Me G Duchesne, expert M. S. Bing, (s.l., s.d), and A. P., D42E3/82.

64 See Pauline D’Abrigeon, Des sciences naturelles à l’histoire de l’art: la porcelaine chinoise dans les classifications françaises du XIXe siècle, in Histoire de l’art 82 (2018), 109-122; and Lucie Chopard, La Céramique chinoise d’Ernest Grandidier: Ecrire une histoire de la porcelaine chinoise en 1894, in Sèvres 27, (2018), 76-86.