ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Najiba H. Choudhury

The confiscation of private properties by the United States of America during WWII is rarely explored. The US government seized the assets of individuals and companies it considered enemies of the State; which included German, Japanese, and Italian nationals. This article highlights the US seizure and liquidation sale of the collection of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. to underscore the need to better study the actions of the US government during WWII and its implications for the discipline of provenance research.

My article builds on Yuriko Kuchiki’s research of the firm, and provides a framework on US policies before and during WWII, in order to facilitate a better understanding of what led to the confiscation of Japanese properties in the US; I incorporated additional legal, governmental, and news sources to provide a more holistic view of this particular seizure. Additionally, my work at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution enabled me to incorporate archival documents from there as well as a few other museums to further elucidate the history of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. during that tumultuous period. Despite its influential patrons and contribution in providing US museums, collectors, and other institutions with Asian art, the Japanese-owned company became enmeshed within the larger geopolitical conflicts between the US and Japan.

World War II (1939-1945) wrought widespread destruction and damage. Among the many wrongs inflicted by the National Socialist regime were the state-sponsored confiscation of art collections from mostly Jewish private collectors, art dealers, and gallery owners. While this has been widely documented,1 less discussed is the confiscation of private properties by the United States of America during World War II. The US government seized the assets of individuals and companies it considered enemies of the state, which included German, Japanese, and Italian nationals. This phenomenon is rarely explored and tends to be neglected within the context of art history and especially provenance research. In this article, I will highlight the US seizure and liquidation sale of the collection of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. to underscore the need to better study the actions of the US government during World War II and its implications for the discipline of provenance research.

The Japanese-owned international firm, Yamanaka & Co., Inc., is discussed in several English and Japanese publications.2 Most notably, Yuriko Kuchiki expounds on the US confiscation of the Yamanaka business in her 2013 Impressions article. Kuchiki extensively researched the dealership’s international operations and the establishment of their different subsidiary companies, especially the New York City gallery, as well as the company’s ultimate demise in the US during World War II. My article builds on her research and provides a framework on US policies before and during World War I, in order to facilitate a better understanding of what led to the confiscation of Japanese properties in the US; I incorporated additional legal, governmental, and news sources to provide a more holistic view of this particular seizure. Additionally, my work at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution enabled me to incorporate archival documents from there as well as a few other museums to further elucidate the history of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. during that tumultuous period.

Well before World War II, the US government paved the road toward legalizing the seizure of private property during wartime. During World War I (1914-1918), the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 was passed on 6 October 1917, just a few months after the US entered the war against Germany and the Central Powers.3 Since its initial enactment, the Act has been amended multiple times to expand its legal authority. It is still an active piece of legislation that can be invoked and applied whenever the US is at war. During World War I and World War II, the law enabled the US to seize, use, administer, and liquidate assets within its borders belonging to individuals whose actions benefited any country or territory or individual the US government considered an “enemy” and was at war with. It also included any companies owned by foreign “enemies”, and vest them as US government properties.4 At its core, the law legitimizes government-sponsored seizure of properties including but not limited to, patents, businesses, incomes, and real estate held within the US and, or US territories that meet at least one of these categories:

1) Belongs to an individual, group, ór a foreign partnership that is declared a foreign enemy by the US government

2) Benefits either an individual in an enemy country or enemy-occupied territory, or the enemy country itself

3) Belongs to an individual who is declared an enemy by the US President.5

It is worth noting that during World War II the US not only seized and liquidated the properties of Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans (often targeting large corporations)6, but also of Germans and to a lesser extent of Italians. A good example of this is the Swiss and German national, Eduard von der Heydt (1882-1964), who was a banker and an art collector. Some of his collection was on loan to the Buffalo Museum of Science in Buffalo, NY. In 1951, the US government alleged that von der Heydt gave money to the National Socialist Party, and under the Trading with the Enemy Act, with a vesting order dated 21 August 1951, the US Attorney General seized forty-four objects which were on loan at the Buffalo Museum of Science. Those objects were eventually transferred to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, and thirteen works that were owned by von der Heydt are now at the Freer Gallery of Art.7

As a result of the Trading with the Enemy Act, on 12 October 1917, through the Executive Order 2729-A, the Office of Alien Property Custodian (OAPC, 1917-34) was established within the Department of Justice. As part of this Executive Order, the Department of Justice appointed a designated Alien Property Custodian, henceforth shortened to APC, whose role was to oversee government-seized assets. The first APC was the ex-congressman, Alexander Mitchell Palmer (1872-1936).8 Within months of his appointment, he was already managing over $135 million worth of assets; prompting The New York Times to declare OPAC as the largest trust company in the world.9 In 1934, the OAPC was abolished, but after the US entered World War II, it was briefly reactivated in the Department of Justice under the name Alien Property Division (APD, 9 Dec. 1941 - 21 April 1942). Critically, rather than place the OAPC within the Department of Justice, the US expanded the OAPC’s power by placing it under the Office for Emergency Management (OEM) of the Executive Branch in 1942.10 This move allowed the US President to assert greater control and make any sweeping changes he deemed necessary. It was the OAPC working as an arm of the Executive Branch which oversaw the seizure of Yamanaka & Co., Inc.’s US branches, and which subsequently in 1944 liquidated the business’s US assets.11

Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was one of the largest dealers importing and selling East Asian art, antiquities, and decorative objects in the United States from the late nineteenth century through most of World War II. The company’s clients included art collecting giants such as the Rockefellers in New York City; Charles Lang Freer of Detroit; Ernest Fenollosa, and Isabel Stewart Gardner of Boston. Freer (1854-1919) was one of the foremost collectors of Asian art in the United States. He founded the Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, DC and collected over 1,598 artworks, mostly Japanese and Chinese but also some Korean potteries, tea bowls, scrolls, and screens, from Yamanaka & Co., Inc. Freer described Yamanaka & Co., Inc. as the “largest company in existence dealing in Japanese Fine Art goods” and further attests to the company’s formidable position among other Asian antiquities dealers in the US by writing that “...nearly all the other dealers in New York buy from them.”12 The dealership brought antiquities predominantly from China, Japan, and Korea, but also sold South and Southeast Asian works. As C.T. Loo is recognized for his seminal role in facilitating the collection of Asian art and antiquities in the US and Europe, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. particularly Yamanaka Sadajirō (1866-1936), was similarly influential for assisting in Asian art collecting in the US.

Yamanaka & Co., Inc. dually benefitted and suffered as a consequence of Japan’s geopolitical relations. As the focus of the discussion here is on US wartime policies, it is important not to take the simplistic view that Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was only a victim of the World War II period, as the dealership had also benefitted from Japan’s imperial policies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When the Yamanaka business brought objects for sale to the US and Europe, Japan was an imperial power, whose policies had serious implications for China, Korea, as well as parts of Southeast Asia. As a direct result of these military actions and the internal turmoil within these nations, for instance, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was able to take advantage of the situation and acquire many antiquities inexpensively from China and Korea. The company acquired objects in Beijing during the so-called Boxer Movement (1899-1901),13 and acquired Prince Kung’s imperial collection and sold it in a New York City auction in 1913.14 In 1917, it purchased the palace of the last Prince Su Shanqi along with his collection in Beijing,15 and converted the former palace to an office.16 A photograph taken in 1926 depicts the Yamanaka staff sitting in the former imperial palace.17 Japan also occupied Manchuria for five months between 1931 and 1932, and waged the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) with China. It took over Korea between 1910 and 1945. During World War II, Japan also expanded into many parts of Southeast Asia, including Cambodia and Indonesia. As discussed in a later section of this article, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. sold objects from all of these regions.

The Yamanaka family opened its first shop in Osaka in the nineteenth century, but it was not until the mid-1890s under Yamanaka Sadajirō that the business would expand internationally. Under Sadajirō’s leadership, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. became a formidable international business empire. He was directly responsible for establishing many of the company’s flagship shops in the US as well as in London, Beijing, Shanghai, and Tokyo.18 Sadajirō was active in the US between 1894 and 1931.

In 1894, Sadajirō, who was adopted as an adult into the Yamanaka family, along with Yamanaka Shigejirō, who was married to the sister of Sadajirō’s wife, arrived in the US to establish a branch in the country.19 Only months after arriving in New York, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was already busy lending out artworks and holding auctions in the city. In March 1895, the company loaned around forty Japanese prints and handscrolls for a two-day show at the Cloister on New York’s Eighth Street. The New York Times described the content of the exhibition as an “...uncommon order of artistic excellence, far removed from the ordinary work familiar to us in the shops, and [...] representative examples of the best in that very progressive country...”20 In 1897, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. sold Chinese bronzes, Chinese and Japanese ceramics, Japanese swords, Buddhist sculptures, and Japanese hanging scrolls at the American Art Galleries in Madison Square South.21

In 1898, Sadajirō moved his New York City gallery to a more permanent building on the fashionable 254 Fifth Avenue.22 In January 1904, a three-day sale at the Fifth Avenue gallery yielded $35,836.23 Aside from the New York gallery, Yamanaka branches opened in Boston, Chicago, and briefly, in Washington, DC. The company also had seasonal locations in the coastal towns of Atlantic City, NJ; Bar Harbor, ME; Newport, RI; and Palm Beach, FL. The latter galleries were open during the summer months for the wealthy American clientele who vacationed in those towns. Out of all the branches, the New York City gallery was the largest of the US-based Yamanaka branches, and it was visited by prominent collectors. Between 1917 and 1944, the New York City gallery occupied a two-floor establishment on 680 Fifth Avenue with ten viewing rooms and a lecture hall.24

The more expensive pieces often went to the New York branch of the company, which was reserved for serious buyers who regularly collected East Asian art. Sadajirō, who was based in Osaka, but frequently traveled from Osaka to China, and then to the US and Europe, spent less time in the US after the company was firmly established. He would personally handle many of the important clients and sought to acquire antiquities to meet their needs.25 A 1914 letter, exemplifies his travels to seek antiquities. In the letter, Sadajirō writes to Freer that he traveled to Shanghai for three weeks and then Beijing for a month to acquire objects. He elaborates that he worked very hard to find important pieces stating: “In China things are so scarce and could not find interesting things, but fortunately I bought very few interesting things and I am sure you will see them later on.”26 It would be wrong, however, to suggest that Yamanaka & Co., Inc. only sold high-end antiquities. The company also sold decorative objects and curio shop items for customers who were more casual in their buying habits and wanted to decorate their homes and/or themselves with fashionable oriental pieces. Notably, an undated sale catalogue (fig. 1a) from the Boston branch advertised Chinese antiquities (fig. 1b) but also gems and pearls (fig. 2), Japanese kimonos, and even decorative objects such as lamps (fig. 3), clearly indicating that the company offered a variety of objects to capture different types of potential clients and also responded to the customers’ desires.27

Fig. 1a: Cover of an Undated Catalogue of the Yamanaka & Company, Inc., Boston

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

Fig. 1b: Chinese Antiquities on Sale in an Undated Catalogue of the Yamanaka & Company, Inc., Boston

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

Sadajirō remained a central figure of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc.’s operation until 1931 when he stopped traveling to the US, and ultimately passed away in Japan in 1936.28 Aside from members of the Yamanaka family including Sadajirō’s son, Yamanaka Kichitarō (who was based in Osaka but periodically came to monitor the US galleries), the business was managed by Japanese managers and sales staff.

Political relations between the US and Japan slowly declined throughout the early twentieth century, as Japan launched military expansions in China, Korea, and further east. For the US, Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, followed later by the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) were demonstrations of Japan’s political ambitions. Official US government correspondences leading up to the country’s joining of the Allied Powers reveal a growing sense of unease towards Japan’s military initiatives.29

A few months prior to Japan’s occupation of Manchuria, in an effort to repair deteriorating relations between the two nations, members of Japan’s imperial family went on an official tour of the US. Prince Nobuhito Takamatsu (younger brother of the then Emperor of Japan, Emperor Hirohito) along with his wife, Princess Kikuko Takamatsu, attended numerous events. One reception organized by the city of Boston was attended by many prominent members of Japanese and Japanese American society, among them, Yatsuhashi Harumichi (1886-1982), the manager of the Boston branch of Yamanaka and his family. The reception’s guest list indicates the prestige and respect that the Japanese expatriates and Japanese Americans enjoyed not only in Boston, but on the East Coast as well, as within the wider US community. This obeisant climate was to shift drastically in the decade to come.30

Figure 2: Oriental Gems Advertised in an Undated Catalogue of the Yamanaka & Company, Inc., Boston

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the US naval base, resulting in 2,300 American military casualties. The following day, the US declared war on Japan and formally entered World War II. This declaration activated the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917. As part of the declaration of war, the US defined all Japanese nationals as enemies of the state and those nationals residing in the US, along with Japanese Americans, began facing hostility. Particularly on the West Coast, Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans were persecuted and their businesses were shuttered. Less than three months after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt ordered the forced relocation of Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans into internment camps on the West Coast.31 Approximately 122,000 individuals were forced out of their homes and relocated to ten internment camps across six states.32

The East Coast had no internment camps, but there was still unease in the region. For instance, the day after Pearl Harbor, the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, which is part of the Federal Government, fearing adverse reactions, removed all Japanese art from display.33 At the time, Kinoshita Yokichi (1880-1952), a Japanese mounter-restorer, who was not only the first Japanese but also the first Asian permanent employee in the entire Smithsonian Institution was employed by the Freer Gallery of Art.34 Despite living and working in the US for most of his adult life, as a result of the US entry to World War II Kinoshita was forced to keep a low profile while working at the Freer to reduce the risk of bringing attention to himself. He often worked from home and was allowed to bring Asian books from the Freer library to his residence to continue work during this wartime period.35 In 1943, the US government seized some of his possessions including a radio, binoculars, opera glasses, and three small Japanese flags which he successfully retrieved after the war in 1946.36 In 1950, at the age of seventy, he retired from the Freer, and after working forty years in the US he returned to Japan; he passed away two years later. On the occasion of his retirement, a newspaper article in Today’s Star mentions how Kinoshita was “thoroughly Americanized” and that he felt, “Japan will appear very different after all these years”.37 That being said, in 1952, the Freer Gallery of Art was able to establish four Federal excepted positions dedicated to non-national “Oriental Art Restoration Specialists” through an Act of Congress that is still active.38 While the treatments of Japanese and Japanese Americans were uneven across the US, depending on the geographic location, nonetheless, the circumstances under which they lived after and during the US engagement with World War II were challenging, to say the least.

Fig. 3: Decorative Lamps Advertised in an Undated Catalogue of the Yamanaka & Company, Inc., Boston

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

By 1942, only three branches of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. were still in business in the US. On 8 July 1942, the OAPC used the Trading with Enemy Act of 1917 to seize the three remaining branches of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc. in Boston, Chicago, and New York City. The Federal Register announcement stated that following an investigation by OAPC, the three subsidiary branches of Yamanaka & Co., Ltd. of Osaka, Japan were found to belong to foreign nationals of “a designated enemy country” and were thus seized.39 That is the only reason the OAPC had to provide to confiscate businesses. The owners of Yamanaka & Co., Inc. including both Yamanaka Sadajirō, who was deceased by this time, and his son and successor to the business, Yamanaka Kichitarō, were both Japanese nationals.40 On the same day, the APC, Leo T. Crowley announced that the Boston and Chicago branches would be inventoried and then open for liquidation of their stock.41 The OAPC not only seized control of the Japanese company’s stocks and inventories but also their real estate.42

During World War II, the US government confiscated not only the property of foreign, enemy-owned companies, but also the small possessions of nationals of designated enemy countries. For instance, a resident of Kanazawa, Japan, J. Imamura purchased a bronze incense burner, and three bronze vases, but had left them in the possession of Tiffany & Co., in New York, where these were confiscated by OAPC in 1943. Imamura had also bought a ceramic incense burner, a lacquer box, and two porcelain vases from Yamanaka’s New York gallery, all of which were also seized.43

In 1943, the OAPC published a sale brochure titled, Collection of Chinese and Other Far Eastern Art. (Fig. 4) In the catalogue, Leo T. Crowley, the APC announced that

The American business of Yamanaka & Company, Inc. is now under the supervision and control of the Alien Property Custodian of the United States of America by virtue of the vesting by the Custodian of 100% of the capital stock of the three American stores of Yamanaka & Company, Inc. located in New York, Boston and Chicago.44

Allen J. Mercher, who was appointed by Crowley as the Chairman of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc. Board, as well as the special representative of the APC, proclaimed that most of the items on sale in the brochure were from China. Moreover, since China is an important ally of US, the APC wanted to give collectors and museums “...an unusual opportunity to acquire at substantially reduced prices...”45 While the majority of the 1,683 objects published in the catalogue were Chinese, there were also paintings, prints and screens, wooden and stone sculptures, and decorative accessories from Japan; paintings and sculptures from Korea; and Buddhist sculptures from Afghanistan, Cambodia, India, and Thailand. Furthermore, no prices were listed; Mercher assured potential customers that they would be happy with the final price.46

Fig. 4: Cover of the 1943 Collection of Chinese and Other Far Eastern Art Brochure

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

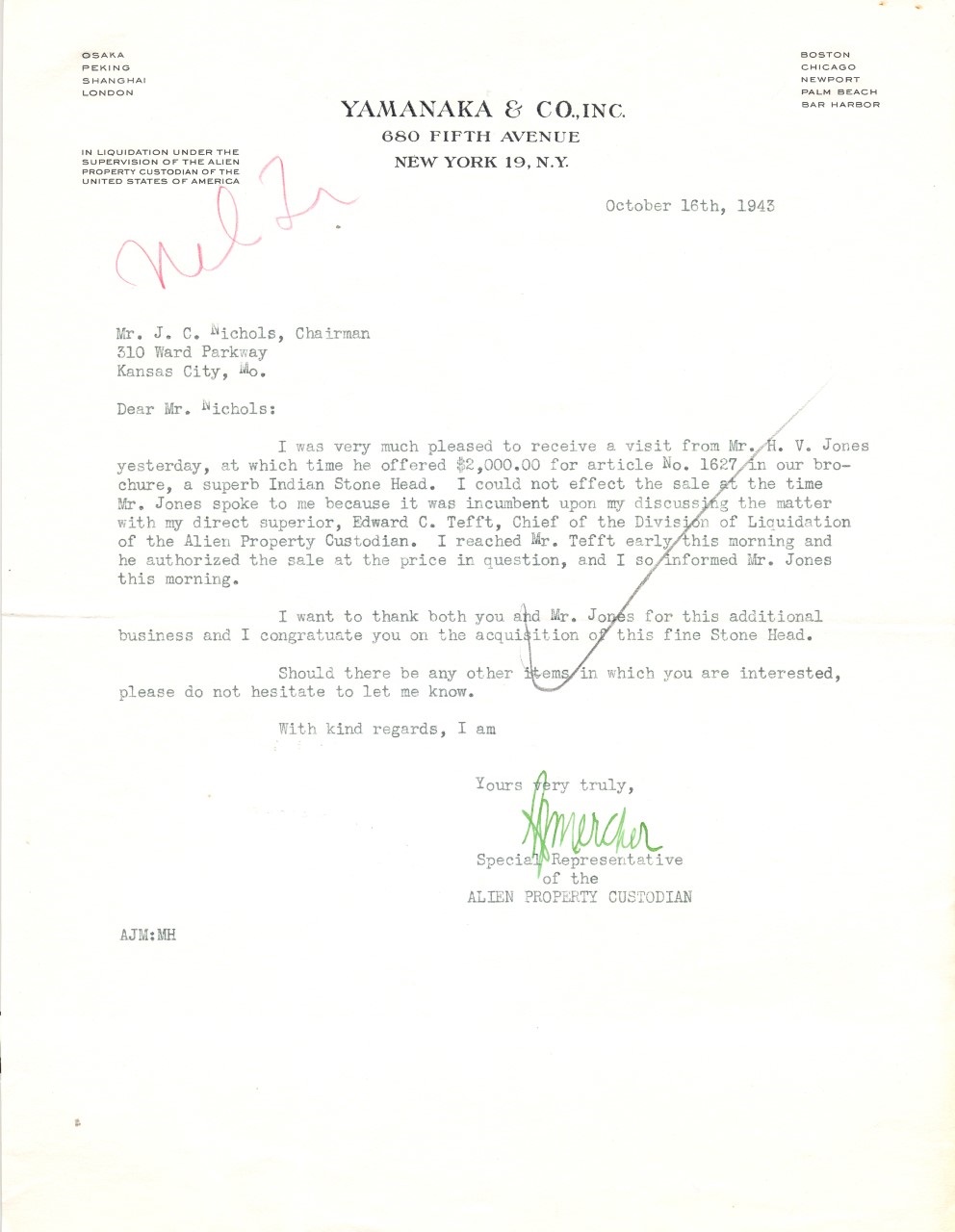

There is evidence that Mercher conducted business with US museums to sell objects from the Yamanaka & Co., Inc.’s published inventory. (Fig. 5) A letter from Mercher to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art’s trustee, J.C. Nichols, dated 16 October 1943, directly refers to an article on sale (ill. cat. #1627) from the 1943 published brochure. Mercher writes how H.V. Jones, another trustee of the museum, visited him in New York City to examine an Indian stone head of Buddhistic deity with, richly adorned crown. (Fig. 6) After negotiating a price and receiving the approval of Mercher’s superior at the OAPC, the head was sold to the museum in Kansas City, Missouri.47 The seized status of the Yamanaka company was made clear also in the official communication documents. Mercher used stationery that listed that Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was “In Liquidation Under the Supervision of the Alien Property Custodian of the United States of America”. The unsold stocks from all the branches of the company were stored in the New York branch by 1943. (Fig. 7) The same year, the Nelson-Atkins purchased one more object from the 1943 brochure: a fragment of a Central Asian wall painting from Turfan taken during an expedition by Le Coq, titled, Fresco painting of the bust of Bodhisattva in attitude of adoration (ill. cat. #390).48 Another object, the porcelain piece (fig. 8) that was printed on the cover of the 1943 Yamanaka sale brochure by the OAPC (ill. cat. #1203) eventually entered the Freer Gallery of Art in 1954 through C.T. Loo & Co., who bought it from H.L. Hsieh of New York.49 Although at this time, it is not known who purchased this vase from the OAPC in 1943, Hsieh sold it to C.T. Loo & Co. in 1949 who in turn offered it to the museum in 1954. Mercher was still negotiating sales from the 1943 sales brochure in the year 1944. He wrote to the Curator of Textiles at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Adele Coulin Weibel, urging her to consider buying from the brochure and indicating the liquidation of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc. was nearing completion.50

Fig. 5: Letter from the Alien Property Custodian

Letter from the Alien Property Custodian to J.C. Nichols on Yamanaka letterhead, 16 October 1943 (Box 3, Folder 35), William Rockhill Trust Office Records, J.C. Nichols Files, RG 80/10. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Archives, Kansas City, MO.

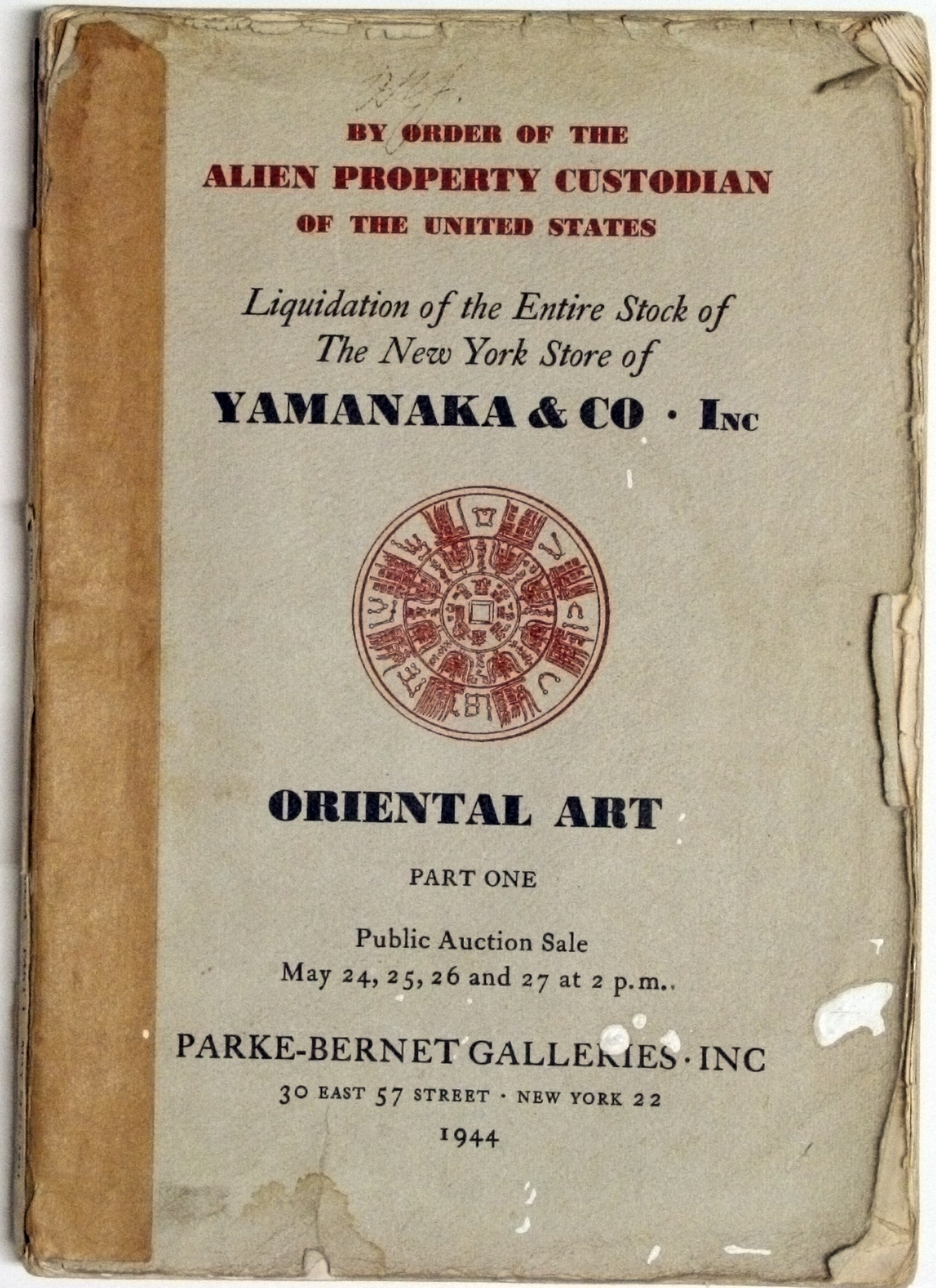

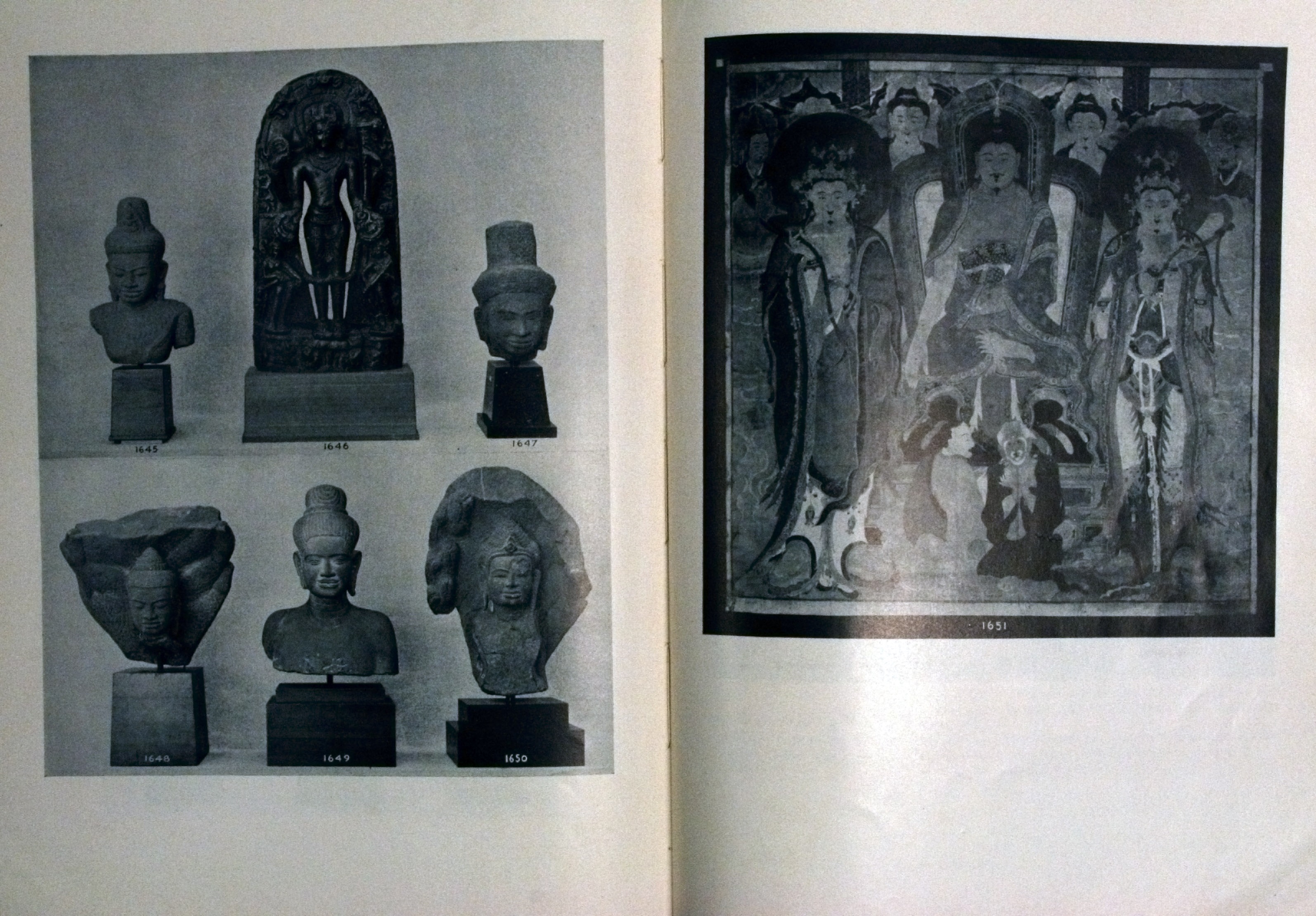

In 1944, the OAPC hired Parke-Bernet Galleries, Inc. in New York City, to organize auctions to liquidate the remaining inventory. The series of auctions was divided into three parts containing the art collection of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc. The Art Library was also auctioned on 6-7 June with 1,037 lots. OAPC did not organize each part of the auctions to exclusively sell a type of object from the Yamanaka stock, rather each category of objects was distributed across the series of sales between May and June. Japanese bronzes, porcelains, potteries, prints, drawings, screens, scrolls, as well as small decorative containers and accessories that are traditionally part of the kimono were on offer. Chinese bronzes, decorative objects, jewelry, lacquers, paintings, porcelains, potteries, rugs, sculptures, and textiles were for sale. East Asian furniture and especially lamps were auctioned. Korean and Tibetan paintings and sculptures were also offered in the liquidation sales. Contrary to common assumptions, aside from East Asian art and antiquities, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. also sold South and Southeast Asian antiquities, especially sacred sculptures.

Part One (fig. 9) was sold in four sessions on 24-27 May 1944. Interestingly, a cultured pearl necklace with 68 graduated pearls (ill. cat. #256) sold for $2,200, one of the highest prices paid for an object at the auction. On another instance, a Korean large-scale painting on silk and hemp that was advertised in both the 1943 sale brochure (ill. cat. #1651, fig. 10) and the 1944 auction catalogue (ill. cat. #230) titled, Important Korean Buddhistic Painting, was purchased by the Hermitage Museum & Gardens in Norfolk, Virginia for $450. The museum donated the painting to the National Museum of Korea in January 2014, after it was discovered that Yamanaka & Co., Inc. removed it from a temple while the country was occupied by Japan.51 Part Two was liquidated over six sessions on 14-16 June with 1,172 lots. Part Three was liquidated over six sessions on 28-30 June with 1,253 lots. Aside from US museums, private collectors and their agents, art dealers, and other antiquities businesses purchased from the liquidation sale. For instance, the above-mentioned C.T. Loo & Co. also purchased objects from the sale. On the first day of Part One sale, Loo bought a Gandharan Head from Afghanistan for $1,200 (ill. cat. #6).52 No estimated prices were published for any of the stocks before they went on sale at Parke-Bernet Galleries.53 The proceeds of all sales went to the US Treasury Department, while a percentage went to Parke-Bernet as commission. By 1945, the OAPC had dissolved the seized Yamanaka & Co., Inc.’s US business.

Fig. 6: Head of a Crowned Buddha

Head of a Crowned Buddha, Northeast India, Bihar, Pala-Sena Dynasty (750-1100 C.E.), late 10th-11th century. Schist, 15 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 8 1/2 inches (39.4 x 26.7 x 21.6 cm). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 43-16. Photo: Jamison Miller

When the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 was established and the first APC was appointed, newspapers portrayed the APC as simply custodians who held and managed assets of foreign nationals designated as foreign enemies, but as time went on it became clear to the media that the US government may not have had that intention.54 At the end of World War I, the treaty signed between the United States and Imperial German Government and the Royal Austro-Hungarian Empire further reinforced the US policy of denying reparation to the German government for the damages caused by Germany during World War I.55 Similarly, after World War II, the defeated Imperial Japan signed the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty with the US, where the Japanese government waived the right to seek restitution for loss and damages caused during World War II; this agreement did not forbid Japanese nationals from requesting restitution.

Figure 7: Fragment of a Buddhist Wall Painting

Fragment of a Buddhist Wall Painting, China, Xinjiang, region of Turpan, Bezeklik, 8th century C.E. Ink and mineral pigments on clay, 17 1/2 x 13 3/4 inches (44.5 x 34.3 cm). Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 43-17. Photo: Jamison Miller

After the end of World War II in August 1945, Yamanaka Kichitarō, in conjunction with some other Japanese businesses similarly wronged during World War II, pursued legal actions in the US. The Vesting Order 6196 in the US. Federal Register from 27 April 1946, stated that the Yamanaka & Co., Inc., and specifically Yamanaka Kichitarō could file a claim with the APC and request a hearing. Simultaneously, the Order also stated that Kichitarō’s last address was in Japan and that as a nation of “a designated enemy country”, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. is the property of the US government. Furthermore, the Order mentioned that nothing in the document “…shall be deemed to constitute an admission of the existence, validity or right to allowance of any such claim.”56 According to Kuchiki’s research, the restitution request by the business was unsuccessful and the Yamanaka family abandoned their claims process in 1960.57

Fig 8: Vase of Bottle shape with “Garlic” Mouth

Vase of bottle shape with “garlic” mouth, China, Jiangxi province, Jingdezhen, Qing dynasty or possibly modern, Qianlong reign, 1736-1795, or possibly early 20th century, H x W: 17.2 x 9.5 cm (6 3/4 x 3 3/4 in). Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC: Purchase — Charles Lang Freer Endowment, F1954.127a-e

Despite the harrowing treatment of the Yamanaka & Co., Inc., and the seizure and liquidation of its business in the United States in 1944, in the 1950s, the company re-emerged in the US. Correspondence from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art attest to the ongoing business relationship between the Yamanaka & Co., Inc. and the museum post-World War II. Letters from as early as 1954 indicate that Yamanaka & Co., Inc. had re-established the firm’s business in New York in a different building. Inouye Kyūshirō managed the New York company in the 1950s.58 In a 1954 letter to the Nelson-Atkins, Inoyue wrote that the Tokyo office was closed, and only the Osaka and Kyoto branches remained in Japan.59 The company continued to conduct business in the late 1950s in New York; the Nelson-Atkins purchased a Tang bowl from Yamanaka & Co., Inc., New York in June 1956.60 As late as mid-January 1959, Inoyue corresponded with the director of the Nelson-Atkins. According to Kuchiki, in New York City, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. finally closed its doors in 1966,61 but the Yamanaka & Co., Ltd. Osaka and Kyoto galleries continued to sell to US museums till the late 1970s.62 Yamanaka’s central branch in Osaka closed in 2003.63 Members of the Yamanaka family still reside in Osaka and Kyoto.64

Fig. 9: Auction Catalogue of the Liquidation of the Yamanaka & Company, Inc., Part 1 (1944)

Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

Yamanaka & Co., Inc. provides a rich example of the need to consider US actions during World War II. Despite its influential patrons and contribution in providing US museums, collectors, and other institutions with Asian art, the Japanese-owned company became enmeshed within the larger geopolitical conflicts between the US and Japan. This article aimed to illuminate the systematic injustices and prejudices enshrined in US legislation and their wider consequences – and the need to interrogate rules, regulations, and laws. The Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 is still active and can be enforced during wartime and national emergencies today. The question remains, how do museums and cultural institutions acknowledge these darker histories of their collections? As World War II provenance research is considered, in addition to discussing National Socialist seizures, forced sales, and sales made under duress, the United States’ history of seizures should also be studied.

Najiba H. Choudhury is the Assistant Collections Information Specialist and Provenance Researcher at the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery.

I am grateful to Tara Laver and Yayoi Shinoda from the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, and Dorota Chudzicka from the Detroit Institute of Arts for their help. At the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, I received assistance from Jennifer Berry, Antonietta Catanzariti, Lisa Fthenakis, Andrew Hare, Sana Mirza, Ryan Murray, Reiko Yoshimura, and Natsue Ueno.

Fig. 10: Korean Painting from the Collection of Chinese and Other Far Eastern Art Brochure (1943) Yatsuhashi Harumichi Collection, FSA.A.1994.02 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Gift of James Arthur Marinaccio, 1994.

1 See Lynn H. Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Vintage Books, 1994); Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (Chapel Hill University of North Carolina Press, 1996); Jonathan Petropoulos, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

2 Yamanaka Sadajirō Okina den (Ōsaka-shi: Ko Yamanaka Sadajirō Okina Den Hensankai, 1939) = [Yamanaka Sadajirō Biography (Osaka: Yamanaka Sadajirō Biography Editorial, 1939)]; Thomas Lawton, Yamanaka Sadajirō: Advocate for Asian Art, in Orientations 26 (1995), 80-93; Yuriko Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader: The United States and the End of the Yamanaka, in Impressions, 34 (2013), 32-53; Yuki Okamura, Japanese Art Dealer - his New York city period 1893-1936 (New York: Fashion Institute of Technology, 2003); Yumiko Yamamori, Japanese Arts in America, 1895-1920, and the A. A. Vantine and Yamanaka Companies, in Studies in the Decorative Arts, 15/2 (Spring-Summer 2008), 96-126; Constance J. S. Chen, Merchants of Asian-ness: Japanese Art Dealers in the United States in the Early Twentieth Century, in Journal of American Studies, 44/1 (2010), 19-46; Masako Yamamoto Maezaki, Innovative Trading Strategies for Japanese Art: Ikeda Seisuke, Yamanaka & Co. and their Overseas Branches (1870s-1930s), in Bénédicte Savoy, Charlotte Guichard, Christine Howald, eds., Acquiring Cultures: Histories of World Art on Western Markets (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2018), 223-238..

3 For an overview of the way the Trading with the Enemy Act has been historically interpreted, expanded, and used, see Benjamin A. Coates, The Secret Life of Statutes: A Century of the Trading with the Enemy Act, in Modern American History, 1 (2018), 151-172.

4 U.S. Congress. United States Code: Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, 50 U.S.C. 2011. Periodical. See also, Paul V. Myron, The Work of the Alien Property Custodian, in Law and Contemporary Problems, 11/1 (1945), 76-91.

5 Myron, The Work of the Alien Property Custodian, 76.

6 For instance, Mitsubishi, Nippon Trading Ltd., and Toyo, among other Japanese corporations were seized by the US.

7 The 13 objects transferred to the Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution include Chinese, Indian, and Indonesian works. The accession numbers for these artworks are as follows: FSC-S-16a-b, F1974.31a-b, F1976.15, F1977.8, F1977.9, F1978.29, F1978.30, F1978.31, F1978.32, F1978.33a-b, F1978.34, F1978.35, F1978.36. For more information on von der Heydt see also, Eberhard Illner, ed., Eduard von der Heydt: Kunstsammler, Bankier, Mäzen (München: Prestel, 2013).

8 See Trading with the Enemy Act 50 U.S.C. §4306 (1817).

9 See Harris & Ewing, How Seized German Millions Fight Germany: First Authoritative Account of the Many-Sided Activities of Alien Property Custodian - Enemy Money is Put into Liberty Bonds, in The New York Times (1857-1922), 27 January 1918, p. 63.

10 For a detailed history of the OAPC see the “Records of the Office of Alien Property” in The Guide to Federal Records in the National Archives of the United States (Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 1995).

11 The OAPC was transferred to Department of Justice in 1961. In 1966, the OAPC was again abolished.

12 See Letter from Charles Freer to W. J. McBride, 6 December 1901, Box 41, Folder 2, Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

13 See Japanese and Chinese Carvings: Remarkable Collection of Old Carved and Lacquered Shrines, Panels, Doors, and Plaques, in The New York Times, 2 February 1903, 9.

14 See The Prince Kung of China (New York: American Art Galleries, 1913). In Sadajirō’s biography there are several photographs of him in the Imperial Palaces including one where he is sitting on a throne in the Forbidden Palace, and outside the Prince Kung’s mansion. In Yamanaka Sadajirō Okina den, unpaginated (see p. 81-83 for illustrations).

Yamanaka & Co., Inc.’s catalogue selling East Asian art in New York City in 1915 astutely comments on the presence of Chinese antiquities in Japan and Japanese collection as opposed to China. Dana H. Carroll, the cataloguer confirms, “In China itself people will tell you: the Japanese get the best of everything here’; and in Japan itself some of the finest Chinese things are found.” See Rare and Beautiful Oriental Art Treasures of Supreme Quality (New York: The American Art Association, 1915), unpaginated.

15 Michael St. Clair, The Great Chinese Art Transfer: How So Much of China’s Art Came to America (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2016), 105.

16 See Lawton, Yamanaka Sadajirō: Advocate for Asian Art, 85-87.

17 Yatsuhashi Harumichi Family Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. The photograph is published in Chen, Merchants of Asianness, 25, fig. 3.

18 Aside from branches in the US, Yamanaka & Co., Inc. had galleries in Beijing, Shanghai, London, Paris, Osaka, Kyoto, and Tokyo. For a detailed list and dates of when all the US-based Yamanaka & Co., Inc. shops were established refer to Kuchiki’s publication.

19 Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, 34-35.

20 See Japanese Paintings and Prints, in The New York Times, 17 March 1895, 4.

21 The total value of objects sold at the three-day sale in March was approximately $6,063 in 1897. (Please note, the last two numbers of four-digit sale figure are difficult to read, hence the exact figure might be off by a few dollars). “A statuette of Buddha” sold for $35 in 1897 money. Another Buddha sculpture sold for $27. Some of the highest prices realized at the auction were for vases including “a vase of Wan-li porcelain” for $345. See The Yamanaka Collection Sold, in The New York Tribune, 11 March 1897, 5.

22 Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, p. 35.

23 The Yamanaka Collection Sold, in The New York Tribune, 31 January 1904, 6.

24 For images of the interior of the New York gallery on 680 Fifth Avenue see Collections of Chinese and Other Far Eastern Art (New York: John B. Watkins Company., 1943).

25 Sadajirō would visit Beijing every year twice, in the spring and fall. See Roy Davids and Dominic Jellinek, Provenance: Collectors, Dealers & Scholars in the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain & America (Oxon: Great Britain: Roy Davids, 2011), 454-455.

26 See the letter from Yamanaka Sadajirō to Charles Freer dated 13 March 1914, Charles Lang Freer Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC., Box 36, Folder 7.

27 Although this Yamanaka & Co., Inc., Boston catalogue is undated, the locations at the end of the catalogue lists the New York branch of the store as residing in 680 Fifth Avenue; which did not open until 1917 and was active until 1944, which suggests that the catalogue must have been produced sometime between 1917 and the early 1940s. See Catalog, undated, Box 1, Folder 16, Yatsuhashi Harumichi Family Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

28 Sadajirō Yamanaka: Head of Fifth Av. Firm, Importer of Oriental Art Objects, in The New York Times, 2 November 1936,. 25.

29 Joseph V. Fuller (ed.), Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1931-1941 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1943).

30 Yatsuhashi Harumichi Family Papers, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Box 1, Folder 6.

31 Executive Order 9066, 19 February 1942.

32 For reference see, Richard Reeves, Infamy: The Shocking Story of the Japanese American Internment in World War II (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2015) and Albert Marrin, Uprooted: the Japanese American experience during World War II (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016).

33 Chase Robinson, After Pearl Harbor, our museum hid Asian art. In coronavirus crisis we are showing it off., in USA Today, 2 May 2020.

34 Kinoshita came to the US in 1910 at the age of 30 and initially worked for the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Starting in the winter of 1924, in addition to working at MFA, Boston, he spent a few months each year working on East Asian paintings at the Freer. He became a full-time, permanent employee in 1932 when the East Asian Painting Conservation Studio was established at the Freer. See Michi Toda, A Quest for the First Asian Employee, in SI Archives Blog, 10 May 2012.https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/quest-first-asian-employee, 10 May 2012; Report of the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1925), 59.

35 Andrew Hare (Supervisory Conservator of East Asian Painting, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery), Personal Interview, 9 September 2019, and 12 August 2020. See also, Robinson, After Pearl Harbor, our museum hid Asian art.

36 Thomas Lawton and Thomas W. Lentz, Beyond the legacy: anniversary acquisitions for the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1998), 43.

37 Nelson M. Shepard, Japanese Expert in Oriental Art Retiring from Freer Gallery, in Today’s Star, August 31, 1950.

38 National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 83 Fed. Reg. 19320. 2 May 2018.

39 National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 7 Fed. Reg. 5207. 9 July 1942.

40 As an important sidenote to readers, even if Kichitarō or other Japanese nationals wished to become US naturalized citizens, the US had made it illegal under the Immigration Act of 1924, and it would not be until the Immigration Act of 1952 when it was possible for those Japanese individuals to gain naturalized citizenship status. See Reeves, Infamy; Azuma, Eiichiro. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

41 Seizes 3 Japanese Stores: Alien Custodian to Liquidate Affairs of Yamanaka & Co., Inc., in The New York Times, 9 July 1942, 3.

42 National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 7 Fed. Reg. 8812. 30 October 1942.

43 National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 8 Fed. Reg. 6694. 21 May 1943.

44 Collections of Chinese and Other Far Eastern Art (New York: John B. Watkins Company, 1943).

45 Ibid., forward, unpaginated.

46 Ibid., forward, unpaginated. See also National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 9 Fed. Reg. 1040. 28 January 1944.

47 Letter from the Alien Property Custodian dated 16 October 1943, RG 80/10, William Rockhill Trust Office Records, J.C. Nichols Files, Box 3, Folder 35, Spencer Art Reference Library, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

48 https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/19942/a-male-figure-possibly-a-bodhisattva-or-devata-fresco-frag?ctx=7d6993b3-d299-4263-be8f-1b5c2ec7fb6f&idx=1 Accession number 43-17.

49 https://asia.si.edu/object/F1954.127a-e/. Accession number F1954.127a-e.

50 Letter from Yamanaka & Co., Inc., dated 7 January 1944, Textile Department Records, Series III, Box, 8, Folder 13, Detroit Institute of Art, MI.

51 See Colin Brady, Repatriation, Hermitage Museum & Gardens, Norfolk, Virginia, 8 January 2014, https://hermitagemuseum.wordpress.com/2014/01/08/repatriation/. The Hermitage Museum & Gardens purchased a total of 12 objects from Part One of the 1944 Liquidation sale out of which the Buddhist painting was the costliest.

52 Yamanaka Sale Begins: Auction for the Alien Property Custodian Yields $40,595, in The New York Times, May 25, 1944, p. 9.

53 I aim to continue research on this series of sales, and one of my interests will be to compute the total sales figure from the auctions.

54 “How Seized German Millions Fight Germany: First Authoritative Account of the Many-Sided Activities of Alien Property Custodian – Enemy Money is Put into Liberty Bonds,” in The New York Times, 27 January 1918, 63. Palmer is Big Business: Now Managing Seized Enemy Concerns Here and in Our Island Possessions, in The New York Times, 15 December 1918, 27.

55 See section 5, Public Law No. 32, Joint Resolution Terminating the State of War Between the Imperial German Government and the United States of America and Between the Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Government and the United States of America, S. J. Res. No. 16, Pub. Res. No. 8, 67 Cong. (2 July 1921).

56 National Archives and Records Administration. Federal Register: 11 Fed. Reg. 4681. 27 April 1946.

57 Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, 49

58 In the correspondence with the Nelson-Atkins Inouye signs his name as “K. Inouye.” Letter from Yamanaka & Co., Inc. dated 26 July 1954, RG 02, Dept. of Oriental Art Records, Box 7, Folder 30, Spencer Art Reference Library, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

59 Ibid.

60 Letter from Yamanaka & Co., Inc. dated 25 June 1956, RG 02, Dept. of Oriental Art Records, Box 7, Folder 30, Spencer Art Reference Library, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO.

61 Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, 51.

62 See correspondence between Laurence Sickman (Director of the Nelson-Atkins Museum) and K. Takahashi, (Managing Director of Yamanaka & Co., Ltd., Osaka) dated 23 June 1964, 26 June 1964, and 5 Sept. 1968, RG 02, Dept. of Oriental Art Records, Box 8, Folder 1, Spencer Art Reference Library, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO. The last correspondence in the museum’s archives is from Yamanaka & Co., Ltd., from Yamanaka Shōji to Laurence Sickman dated 27 February 1978. According to Kuchiki, the Kyoto branch closed in the 1980s, and the Osaka branch closed in 2003 (Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, 51-52).

63 According to Kuchiki, The Enemy Trader, 52.

64 Yayoi Shinoda (Curatorial Assistant, East Asian Art, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art), Personal Correspondence and Interview, 14 February 2020 and 19 March 2020.