ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Project Report

by Ulrich Weitz

ABSTRACT

Eduard Fuchs (1870-1940) was one of the most successful authors of popular books on cultural history in Germany around 1900. Quite a number of his books were based on documentary images or artworks, which may have inspired him to form his own collection. Notably, he owned prints by Honoré Daumier and paintings and sketches by Max Slevogt and Max Liebermann. This essay is the first attempt to record his East Asian collection, which is almost unknown although more than one thousand East Asian objects were auctioned at Lepke in 1937 and 1938; and Fuchs’s books entitled Tang-Plastik. Chinesische Grabkeramik des 7. - 10. Jahrhunderts, on Tang sculpture, and Dachreiter und verwandte chinesische Keramik des 15. bis 18. Jahrhunderts, on Ming roof riders, became standard publications on Chinese decorative art. Fuchs’s political background as a Socialist enabled him to analyze colonialism and art pillage, while being aware of national liberation movements at an early stage. Establishment experts in Chinese art such as Otto Kümmel criticized him because of his Marxist approach to art history, but the left-wing philosopher Walter Benjamin regarded him as a pioneer in the discovery of the qualities of Asian decorative art.

This essay is based on an ongoing provenance project that was initiated by Fuchs’ heirs and funded by the German Lost Art Foundation. With the active support of museums and many researcher colleagues, fourteen objects could be traced to date, including highlights of Eduard Fuchs’s famous roof rider collection.

Eduard Fuchs (1870 - 1940) was a well-known and successful author in Berlin at the beginning of the twentieth century. His History of Morals (issued from 1907 onwards) earned him more than a million Marks. This income allowed him to form his art collections, which he frequently used to illustrate his publications. He also had an account with his publishers to purchase objects in order to illustrate his books.1

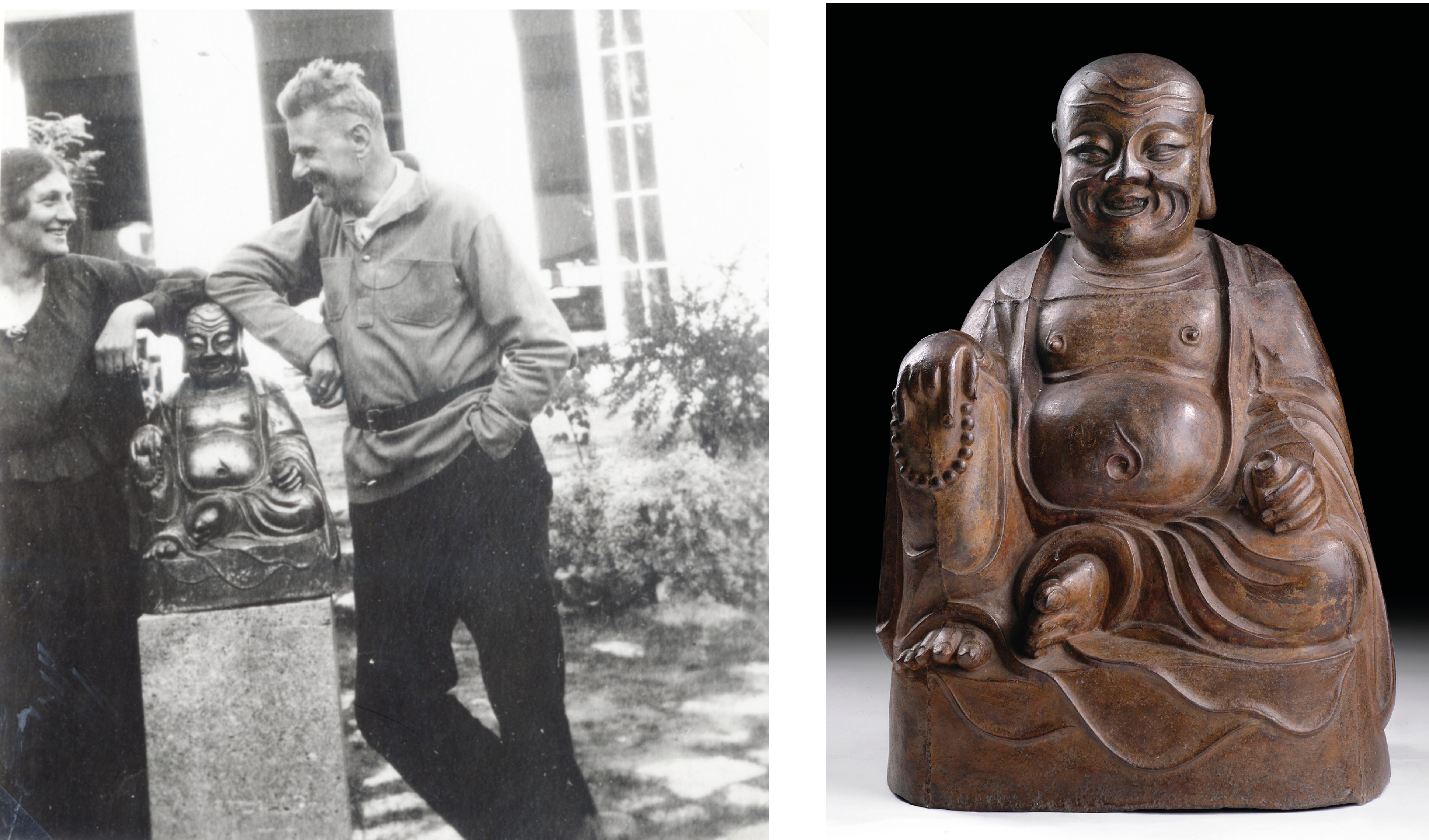

Fig.1 (left): Undated photograph of Margarete and Eduard Fuchs in front of a cast-iron Budai in the Chinese garden of their Zehlendorf Villa © Archive Dr. Ulrich Weitz, Stuttgart

Fig. 2 (right): The Budai included in a forced sale at Lepke in 1937, reappeared at auction with Nagel in 2014 © Auktionshaus Nagel, Stuttgart

Fuchs owned the largest private collection of woodcuts and lithographs by Honoré Daumier.2 He also had an excellent collection of German Impressionism by artists such as Max Slevogt or Max Liebermann, and around 1912 he started to collect decorative art from East Asia, specifically Tang sculptures and Ming roof riders. He also devoted himself to politics. From 1886 to 1914 he was member of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), from 1918 to 1928 of the Communist Party (KPD), and from 1928 to 1940 he joined the small Communist Party Opposition (KPO). Eduard Fuchs emigrated four weeks after the Nazis came to power, first to Switzerland and later on to Paris. On 25 October 1933 his villa, including his library, archive and art collection were confiscated by the Gestapo. Most of his books were banned and some of them were even publicly burned. From 1937 to 1938 his daughter Gertraud had to liquidize the art collections to pay the Reichsfluchtsteuer (Reich Flight Tax) imposed by the National Socialist regime.

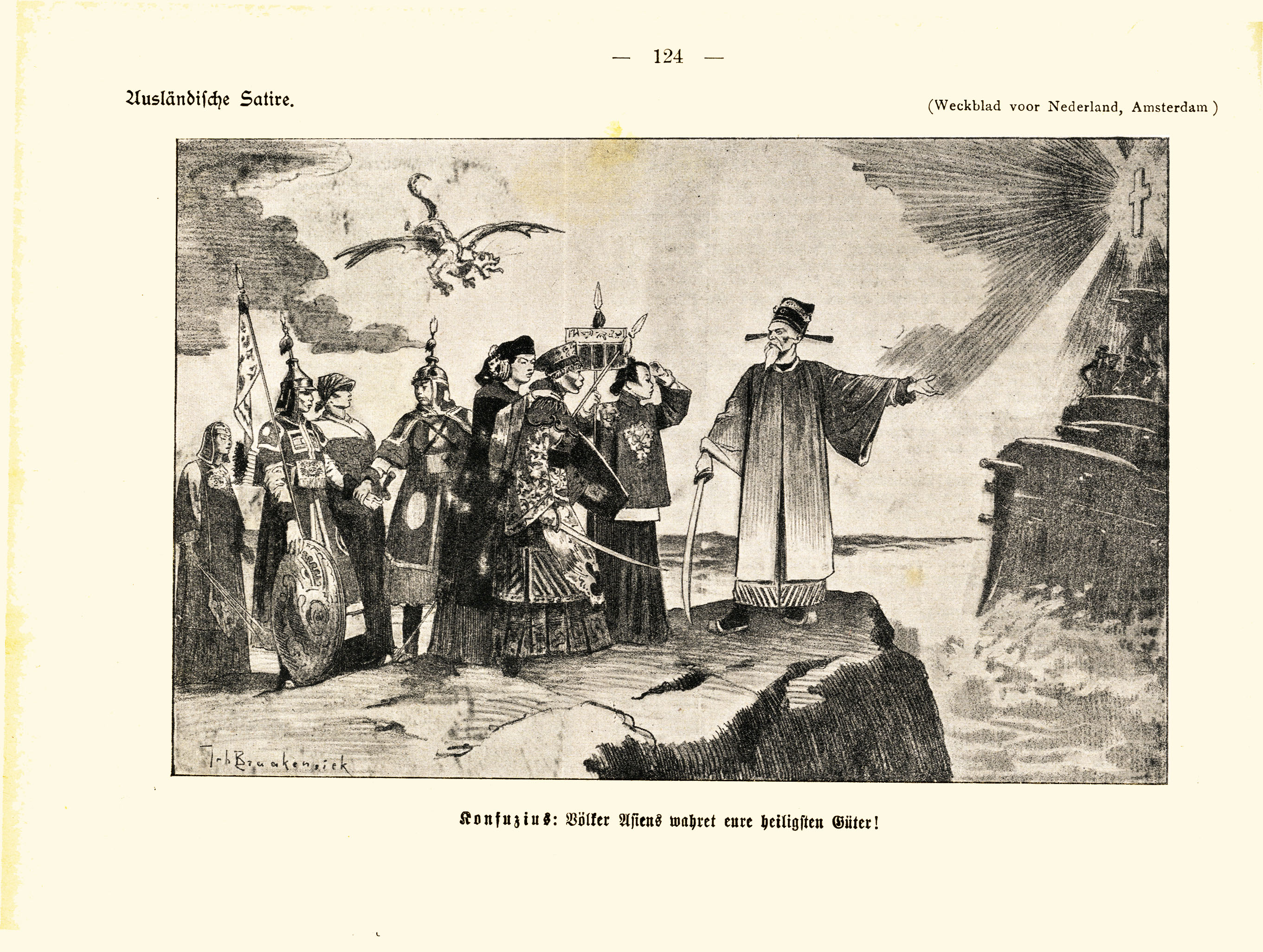

Fig. 3: Caricature by Johann Brakensiek in the Journal De Amsterdamer dated 24 June 1900 © Archive Udo Achten, Düsseldorf

Fuchs’s political position as a Socialist shaped his perspective on colonialism and art pillage while making him aware of national liberation movements at an early stage. In 1916, he analyzed the situation in China in his book Der Weltkrieg in der Karikatur as follows:

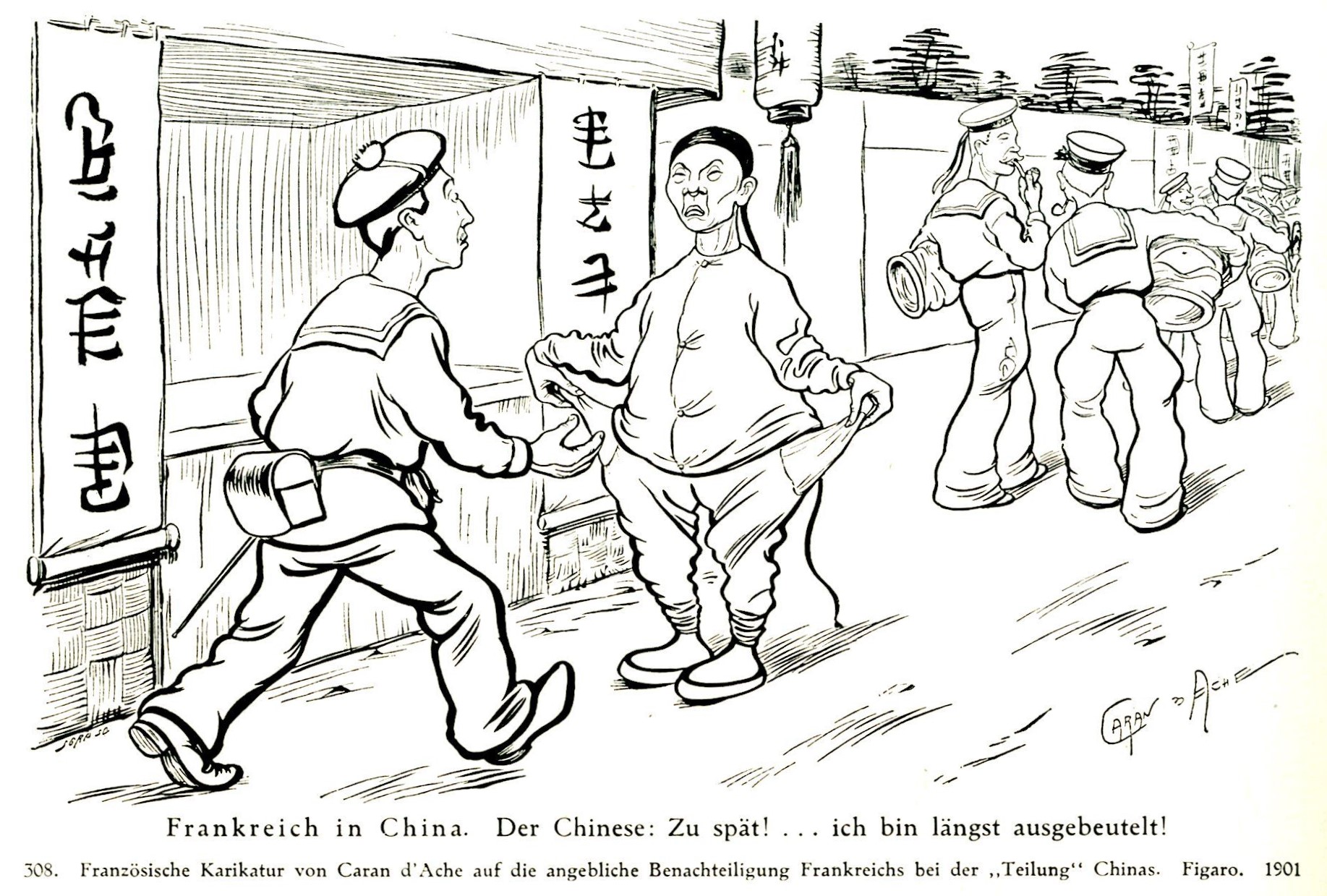

To divide the giant empire China and to secure as valuable pieces as possible ... was one of the earliest projects of the states engaged in global/Imperialist power politics. This desire and the corresponding undertakings of England, France, Russia and in this case also the United States of America date back to the 1860s and 1870s, while Germany only turned to China from 1897 onwards.3

In the same publication, Fuchs also addressed the topic of “pillage”:

In 1842, England forced the poison on the Chinese people in the Opium War, which was victorious for England ... The same applies to the war that England and France waged together against China from 1856 to 1860, and which will always remain notorious for the shameless plundering of the magnificent Summer Palace by the Bonapartist soldiers.4

Despite his political views, Fuchs built up his own collection of artefacts from China. His enthusiasm as a collector mattered more to him than the ethics of handling looted art. In his book “Dachreiter,” he refers to this dilemma, but continued to buy objects that had been fixtures of temples.5

Fig. 4: French caricature by Caran d'Ache on alleged discrimination against France in the looting (Too late! My pockets have long been empty!) reproduced in Eduard Fuchs, Weltkrieg in der Karikatur. Bis zum Vorabend des Weltkrieges (München:Langen 1916), 348 © Archive Dr. Ulrich Weitz, Stuttgart

Fuchs’s collecting activities began years before his books would appear. It may therefore be surmised that he started to buy Chinese artworks from 1912 and continued during World War I and at the beginning of the Twenties.6 During the war he was able to travel to Switzerland to support the peace movement and to Sweden as the Marxist Spartacus League’s contact person for the Russian Bolsheviks. In order to camouflage these conspiratorial activities, he told his friends that he would travel to those countries to buy art, as prices were low in those turbulent times. Unfortunately, few traces remain concerning the source of those antiquities. What is certain is that he was one of the first customers of Theodor Bohlken,7 who had opened his store “Import aus China und Japan” (Import from China and Japan) in Berlin at the corner of Kurfürstenstraße 122 / Nettelbeckstraße) in 1919.8 However, Fuchs was very resourceful in finding art in unusual places (flea markets and small galleries), often at very cheap prices.

Fig. 5: Entrance hall with Asian objects in the Fuchs villa

© Ullstein Bild – Emil Leitner – ub no. 01039140

His second wife Margarete Fuchs, née Alsberg (1885 - 1953) played a major role in building up their East Asian collection. In 1920 he had married this talented artisan, whose silk batik scarfs were exhibited at the legendary Sonderbund exhibition of 1912 in Cologne. Fuchs deferred to her on some aesthetic points, especially on how to present the artworks in their villa in the Zehlendorf suburb of Berlin, or how to photograph objects like the Tang sculptures or the roof riders. She was the daughter of Louis Alsberg, the Jewish founder of a department store chain “Gebrüder Alsberg”. Her fortune of 100,000 Marks and his abundant author’s fees provided them with the necessary means to build an extensive collection.

When Frau Erdmann-Macke, wife of the famous modern painter August Macke, visited the Fuchs villa, she recorded a personal impression of the East Asian collection of Eduard and Margarete Fuchs in her diary for 1928: “Already in the hallway there were glass-cabinets with wonderful ceramics, Chinese horses, porcelain cups, vases, small bottles. On the wall beautiful silk paintings and in the centre a large bronze of a Kwannan [sic], the Japanese patron goddess of the house”.9

Fig. 6: The Chinese Garden of the Fuchs villa designed by Karl Foerster, Potsdam. The two Chinese roof riders and the Budai had been sourced in Vienna, Berlin and Stuttgart.

© Ullstein Bild – Emil Leitner – ub Nr. 01039138

The grounds of the Fuchs villa had been designed as a Chinese garden by Karl Foerster, a Potsdam horticulturalist and garden philosopher. In this setting Eduard and Margarete Fuchs displayed two Chinese roof tiles, on the left a “Rider with a sacrificial bowl on a mythical creature” and on the right “A Dragon with a guide”. Between them at the back they placed a cast-iron sculpture of the legendary Budai from Chinese lore.

Fig. 7: Roof rider “Dragon with a guide”

© Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Later, in French exile, Fuchs compiled a typewritten list in 1933 of the “main components of great art of the Fuchs collection”, which gives a perfect impression of the artworks Margarete and he owned:

“Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings: 13 Tibetan temple pictures, painted on silk, among these some of the most beautiful that exist / Several Chinese temple pictures / 25 valuable Japanese and Chinese Kakimonos (watercolours), some from earlier centuries.

Sculptures: A collection comprising 90 pieces of Han and Tang sculptures (Chinese burial objects from the 6th - 10th centuries) including about 80 numbers which formed the basis of my book “Tang Sculpture” / A collection of 125 items of roof riders (Chinese temple crowns), probably the largest collection of this type in existence. Basis of my book “Dachreiter” / A Buddha head made of basalt from the 4th - 5th century, which could be placed next to the greatest works of art of Greek antiquity and of which, according to the judgement of specialists, there are only about 20 of similar quality in the world / Around 100 Chinese and Indian Buddha statues, Animals and Vessels / Several Chinese and Japanese wood and ivory sculptures / 2 Chinese marble Fo dogs at the entrance to the house.

Applied Arts: A collection of valuable Japanese sword guards (Tsuba), about 300 pieces / Japanese lacquerware, 80 – 100 pieces / Chinese snuff bottles, 100 pieces / Chinese deities carved in amber, 3 pieces / Sceptres for Mandarins, 3 pieces / Chinese carpets, 9 pieces / Chinese temple curtain, 18th century, 3 x 4 metres / Chinese embroideries, 17th and 18th centuries (Imperial Coats etc.), a very large collection / Japanese screens, 17th and 18th centuries (very precious), 5 pieces / Chinese faience and stoneware vessels, 9th century / Chinese embroideries, 17th and 18th century (Imperial Coats etc.) - 17th century, ca. 100 pieces / Chinese porcelain, plates, vessels and figural sculptures, 15th - 18th centuries, several 100 pieces / Early Japanese swords and daggers in lacquer, bronze and ivory sheath, 10 pieces / Japanese sword ornaments, 17th and 18th centuries, large collection / Objects made of jade and rock crystal, Chinese, approx. 10 pieces.10

Fig. 8: The huge yellow dragon measuring 102 cm in length

© Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

Yet despite this impressive wealth of material, Fuchs was rather an outsider in German East Asian art collector circles. While the artist group Berlin Secession and the gallery owner Paul Cassirer had strongly supported him since his move to Berlin in 1901, he was unable to gain a comparable level of acceptance by the Society for East Asian Art, founded in Berlin in 1926. Whether it was his approach to collecting or his political convictions that met with rejection remains unclear.

Fuchs’s interpretation of the historical development in China based on the materialist conception of profit orientation generated fierce resistance among the Orientalists of his time. Otto Kümmel, at that time director of the museum of East Asian art in Berlin and founder of the prestigious journal Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, felt provoked by Fuchs statements and sputtered in a book review in the journal Deutsche Bauzeitung: “,The devout fervour with which the omnipotence of the economy is testified to the Marxist dogma is novel, at least in art research ... The author, faithful to his doctrine, sees salvation precisely in mediocrity”.11

In contrast, the cultural philosopher Walter Benjamin seems to have had a more congenial understanding of Fuchs’s approach as a collector. They met several times in exile in Paris, and Benjamin wrote in his 1937 essay “Eduard Fuchs - Collector and Historian”:

What is fundamentally new in his intention finds direct expression primarily where the material meets it halfway. This occurs in the interpretation of iconography, in his contemplation of mass art, in his examination of the techniques of reproduction. These are the pioneering aspects of Fuchs’s work, and are elements of any future materialistic consideration of art.12

In concrete terms, Benjamin regards the collector’s assessment of the Tang era culture as an important contribution:

That is why there is complete anonymity in these burial objects, the fact that not even in a single case the burial gift means that one knows the name of the individual creator. This is an important testimony of the fact that there never is a question of individual production [in this case], but rather a concern with the way in which the world and things are grasped as a whole ... Fuchs was one of the first to expound the specific character of mass art and thus to develop the impulses he had received from historic materialism”.13

When reading his book on Chinese roof riders, a leitmotiv of the collector becomes apparent. As he put it, “this is nameless folk art. There is no book of heroes that bears witness to its creators”.14

Fig. 9: “Mongolian Pony” roof rider © Museum

Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

Since the 1920s, Eduard and Margarete Fuchs had been pursuing a great dream: they wanted to create a collector’s museum open to the public, in order to present their extensive art holdings.15 Their conception was innovative at that time: the founders wanted to donate their villa designed by Mies van der Rohe (Perls House), including a new museum wing also to be designed by the same architect, the complete collection of artworks, and an endowment of 60,000 Marks to the City of Berlin.16 However, these plans could not be realized.

Immediately after the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Reich Chancellor on 30 January 1933, Eduard Fuchs tried to organize resistance. In early February, fifty intellectuals, academics, and artists, including members of the Jewish cultural sphere met in his villa on the lake Krumme Lanke. Fuchs opened his speech with the words: “That all our heads will be at stake in the future and that we must join forces, and do so immediately, to fight against the danger of Hitler”.17

On 27 February 1933, the day of the Reichstag blaze, the Gestapo surrounded the Fuchs villa. Margarete Fuchs warned her husband by phone and Elisabeth Gräfin von der Schulenburg saved Fuchs’s life because she hid him in the allotment area “Schmargendorfer Alpen”. Eduard and Margarete Fuchs probably crossed the Swiss border in Schaffhausen in the first week of March.

On 25 October 1933, the day of the confiscation of the villa and its contents, Robert Diels, the president of the Berlin Gestapo wrote: “The material already in the house will be used for an exhibition of cultural-Bolshevik conspiracy”.18

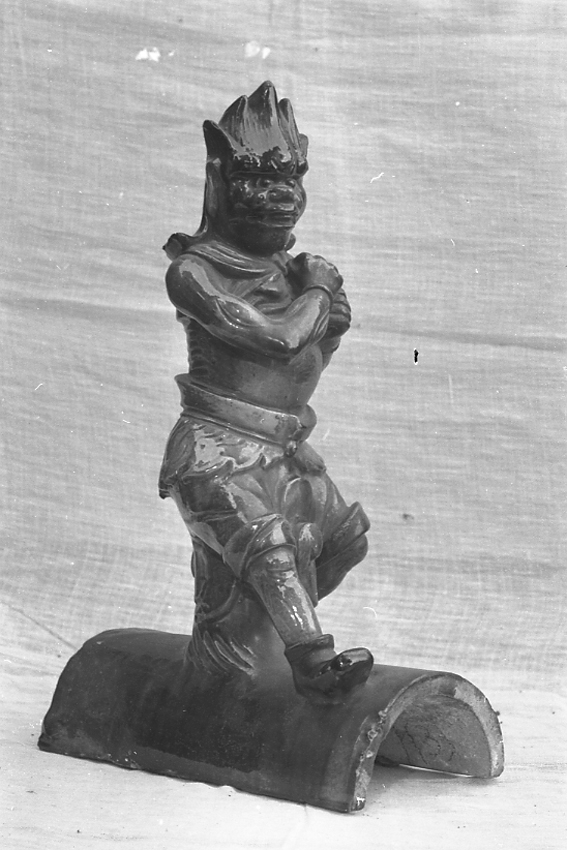

Fig. 10: “Devil with clenched fists” roof rider

© Museum Angewandte Kunst, Frankfurt am Main

At the beginning of 1937, the Reich Fiscal Court determined that Eduard Fuchs had emigrated and on 24 February 1937, the tax office levied the Reich Flight Tax amounting to 29,552 Reichsmark.19

Under these circumstances the liquidation of the collection appeared as the only solution. Eduard Fuchs subsequently instructed his daughter and his lawyer Rudolf Proell, to sell the artworks. The East Asian works of art [catalogue 2115: 799 lots] were auctioned on 15 and 16 October 1937 at Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auktions-Haus in Berlin. A small part, which had not been auctioned, was then sold at Lepke’s from 30 November to 1 December 1937 [catalogue 2117, 29 lots) and from 22 to 24 June1938 [catalogue 2124: 52 lots]. Fortunately an annotated catalogue of the October 1937 auction was preserved at the RKD Netherlands Institut of Art History, The Hague. In the annotations the names of the buyers, the estimated prices and the hammer prices were recorded. The spectrum of buyers included many identifiable art dealers like the managing director Heinrich Peters of China-Bohlken (Berlin), G. Eger (Stuttgart), Anton Exner (Vienna), Hans Krenz (Berlin), Erich Zintl (Berlin) etc.

In addition, the Berlin commission agents G. Albrecht, Adolf Bodenheim, Carl Braunstein, Harald von Münchhofen, Walter Pirschel and Fritz Rehbein played an important role as intermediaries, especially for museums. But museum directors like Otto Kümmel or ministers like Hjalmar Schacht also bought at this sale.

On 26 January 1940 Eduard Fuchs died in exile in Paris, shortly before the German invasion of the French capital. His Jewish wife Margarete was brought to the Camp Gurs in August 1940. As her American friends were able to secure a visa for the United States, she escaped via Toulouse to Lisbon where she set sail on the steamboat “Siboney” to New York, arriving on 23 November 1940.

With the launch of a research funding line for private individuals at the German Lost Art Foundation (Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste) in 2018,20 two of the heirs of Margarete and Eduard Fuchs, Dr Bernhard and Rosemarie Kosel, were able to initiate a provenance research project on the Fuchs collections with the aim of tracing the dispersed objects. At that time, hardly anything was known about the Eduard Fuchs collection of Asian objects. The single most important reference were the illustrated books by Eduard Fuchs himself, Tang Sculpture and Dachreiter. These include illustrations of almost 100 objects from the collection. The annotated copy of the Lepke auction catalogue with the names of the buyers and the prices, at the Netherlands Institute for Art History in The Hague was also vital. In the summer of the same year the official typewritten auction protocol of the “Reichskammer für Bildende Künste, Landesleitung Berlin” was discovered in the Landesarchiv Berlin, which made it much easier to identify buyers of these objects, especially as it also listed the names of those buyers who had commissioned middlemen to act in the sale on their behalf.21 As a first step, a list of the roof riders was registered in the search section of the German Lost Art Foundation’s database lostart.de.22

The first object had been found in in the “online collection database” of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB).23 It was described in Fuchs Dachreiter as the “Dragon with a guide”:

Another similar mythical creature but probably from a somewhat younger period is shown in plate 8, where the male figure is standing next to his strange mount in the same sacrificial manner. This piece is of special interest because of the tiger crouching on the back of the monster, whose function according to Chinese custom is to repel winds dangerous to the house.24

In the Zentralarchiv of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin invoices could be retrieved that identified the Gallery Ernst Fritzsche as the seller of the work currently held by the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. In 1934, this gallery had been commissioned with the appraisal of the Fuchs collection. Fritzsche had cooperated with the Gestapo in handling stolen goods and had made an offer to buy the total collection for the paltry sum of 3,225 RM.25

A comparison with photo material and other documents proved beyond doubt the identity of the lost work with the sculpture in the Ethnological Museum. As shown on a private photo from the garden of the Fuchs villa (1925), “Dragon with a guide” was located outside and therefore exposed to the elements. Especially the area from the body to the bent arm filled with water when it rained. This was found to be consistent with a change of colours on inspection by the conservator in charge. After three months we received a letter from the President of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Prof. Dr. Hermann Parzinger, confirming our view that this object had indeed been seized due to persecution.

The registered search for roof riders on lostart.de also prompted the provenance expert at the Museum Angewandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Arts) in Frankfurt am Main to identify three further objects from the Fuchs collection. These had been donated to the museum in October 1943 by the collector Carl Cords from Zoppot (Sopot, near Gdansk). One is a dragon measuring 102 cm, currently on display in the museum’s permanent exhibition entitled “Elementarteile” (Elementary Parts).

Another roof rider from the donation by Carl Cords was also found in the museum in Frankfurt. It is shaped as a Mongolian pony and was illustrated in reverse on the cover of Fuchs’s book “Dachreiter”. The third find from the Carl Cords donation is a Chinese roof rider in the shape of a “Devil with clenched fists”, which the museum no longer holds. It was sold among others on 13 May 1957 at Hauswedell auctioneers in Hamburg.

A cooperation with the auction house Nagel in Stuttgart, which holds Asian art auctions in Salzburg, cast light on yet another aspect. Michael Trautmann, Nagel’s Asian expert, contacted the German Lost Art Foundation that the firm had received a consignment for sale at auction on 6 December 2018, most likely containing objects seized due to persecution. The current holder was aware of an Eduard Fuchs provenance for two roof tiles shaped as mermaids. The annotated Lepke catalogue proved that the art dealer A. Eger of Stuttgart had bought them at the auction in October 1937 for 270 Reichsmark. Further research through Nagel also yielded a cast-iron “Budai” formerly in the garden of the Zehlendorf villa. This sculpture had remained unsold when offered at auction with Nagel in 2014.

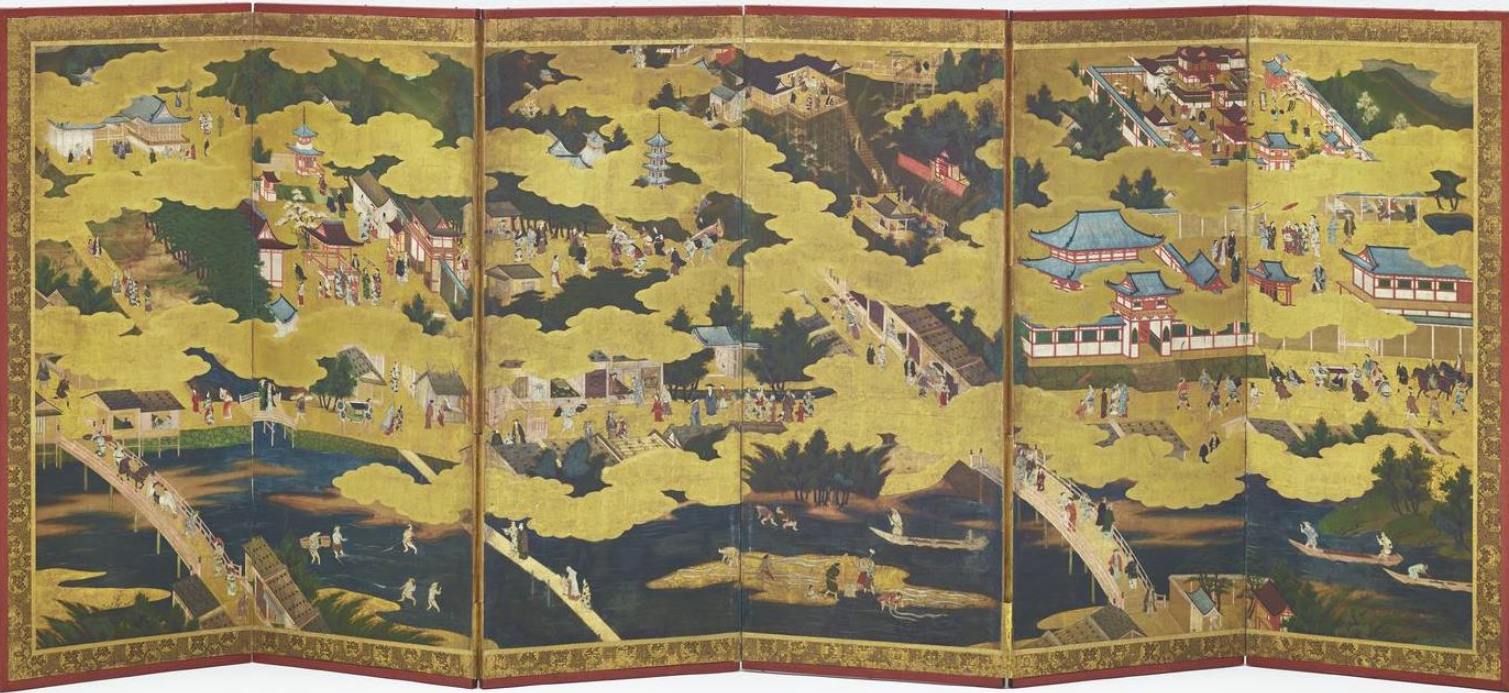

The most interesting discovery was made with the assistance of provenance expert Leonhard Weidinger at the MAK - Museum für Angewandte Kunst (Museum of Applied Arts) in Vienna. The Asian collection in this institution held important pieces from a donation by Anton Exner. The Vienna-based gallery owner and Asian art collector Exner had joined the German National Socialist Party as early as 1931 (party membership no. 782.343). He was a frequent valuer of Asian artworks seized from Jewish collectors, mainly commissioned by the Dorotheum auction house in Vienna.26 In October 1937, Anton Exner bought nineteen objects from the Fuchs collection, according to the annotated Lepke catalogue. The provenance team of the MAK especially welcomed the discovery as they had not yet been able to prove that Exner had dealt in looted art. They subsequently found eight additional objects from the Fuchs Collection, including two of its highlights. The first is a paravent with six panels depicting Kyoto, measuring 118 cm in height and 290 cm in length.

Fig. 11: Paravent with six panels, ink, colours and gold on paper, depicting the Temples of Kyoto

© MAK Vienna

Fig. 12: “Rider with a sacrificial bowl on a mythical creature” roof rider © Private Archive Ulrich Weitz

The object described as “Rider with a sacrificial bowl on a mythical creature” had been acquired by Anton Exner at the Lepke sale for a mere 55 Reichsmark. He bought three further roof riders, also published in Fuchs’s book “Dachreiter”, and an additional one reproduced in the Lepke sale catalogue no. 2115. The annotated catalogue also helped to locate a roof rider in the shape of a goat, of which no illustration had been available. Exner bought even more: a sceptre, porcelain figurines, vases, decorative plates, and bowls. No images of these objects exist.

The results of the first two years of the project are quite encouraging. With the help of colleagues in Berlin, Frankfurt, and Vienna, twelve Asian objects from the Fuchs collection could be rediscovered. The cooperation with the auction house Nagel in Stuttgart proved instrumental in tracing two further objects. While the total is still small compared to the missing eight hundred objects, the roof riders and the Japanese folding screen are masterpieces representative of the Fuchs collection.

Ulrich Weitz is a provenance researcher and manages the Agentur für Kunstvermittlung.

1 As noted in a memorandum by the publishers Langen, Fuchs disposed of a large budget from his publishers to purchase artworks for illustration in his books: “There are years in which 40,000 and more Goldmarks were spent on the procurement of materials for Fuchs’ cultural and moral history works.” (Memorandum from the Albert Langen Verlag on the academic work of Eduard Fuchs dated 1927, 34, author’s translation).

2 Josef Anton Bondy, Eine Privatsammlung in Berlin, in Neue Revue, 29 May 1909, no. 22/23: “Fuchs has no less than 3,800 Daumier prints; the Berlin Kupferstichkabinett owns barely 50 of them, and even the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris cannot beat him in this number. While only a dozen or so pieces by Rowlandson can be found in the Berlin cabinet, Fuchs owned over 300” (author’s translation).

3 Eduard Fuchs, Der Weltkrieg in der Karikatur (München: Langen, 1916), 352 (author’s translation). In general, Imperial expansion and pillage of cultural assets in China were viewed critically in Europe, Russia and the USA at that time. Discussions about violent actions against the Chinese and looting, which took place not only in Beijing but throughout northern China, pervaded daily newspapers as well as government debates, though there was a general tendency to blame the responsibility on other nations involved. See for example: Toralf Klein, ed., The Boxer War, Media and Memory of an Imperialist Intervention (Kiel: Solivagus-Verlag, 2020).

4 Fuchs, Der Weltkrieg in der Karikatur, 357-358 (author’s translation).

5 Eduard Fuchs, Dachreiter und verwandte chinesische Keramik des 15. bis 18. Jahrhunderts (München: Langen, 1926), 39: “Even if there is no actual protection of historical monuments in China, there is still xenophobia which quickly ignites when temples are demolished, and even the unscrupulously expropriating exporter of Chinese art has to take some account of this.” (Author’s translation).

6 Fuchs dates the beginning of his collection quite precisely in Tang-Skulpturen: “My material for this publication has been collected directly for this purpose over the last ten to twelve years”, 11.

7 In a personal interview by the author with he famous architect Ferdinand Kramer (1898-1985), who often visited the Fuchs villa in the Twenties (July 1981), Kramer stated that Fuchs bought Chinese terracottas in a small shop at Kurfürstenstrasse in Berlin.

8 See: Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, The trade in Far Eastern Art in Berlin during the Weimar Republic (1918-1933), in Journal for Art Market Studies, vol. 2, no.3. https://doi.org/10.23690/jams.v2i3.57.

9 Author’s translation. Her description of the entrance hall is confirmed by a photograph by Emil Leitner for the illustrated home story “Das Heim des Kulturhistorikers Eduard Fuchs in Zehlendorf bei Berlin”, published in 1928 in the women’s magazine Die Dame, no. 15.

10 Quote from the list “Hauptbestandteile an großer Kunst der Sammlung Eduard Fuchs” published 1933 in Paris (Exile Archive of Eduard and Margarete Fuchs at Stanford University, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace: Nicolaevsky Collection 1801-1982. In Series N°264, Box 617, Folder 6 (translation by the author).

11 Otto Kümmel, Eduard Fuchs. Kultur- und Kunstdokumente, in: Deutsche Bauzeitung 1924, no. 49, 386. Rudolf Grossmann appears to refer to this conflict in his portfolio Fünfzig Köpfe der Zeit (Berlin: Mosse, 1926) when he commented on his caricature of Fuchs: “A small excursion into a hitherto foreign territory finally brought the Chinese ‘roof riders’ close to him. But the specialist science is narrow and strict: it seems to resent the Daumier expert, this Chinese flirtation.”

12 Walter Benjamin, Eduard Fuchs, Der Sammler und der Historiker, in Zeitschrift für Sozialforschung vol. 6, 1937, 346-380, quoted from Walter Benjamin, Das Kunstwerk im Zeitalter seiner technischen Reproduzierbarkeit (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1977), 81f.

13 Walter Benjamin, Eduard Fuchs, 105 (author’s translation).

14 Eduard Fuchs, Dachreiter, 45 (author’s translation).

15 Letter from Eduard Fuchs to Max Slevogt dated 8 July 1921: “Since my wife and I pursue the same ideal, namely that the main parts of my collection should one day become public property, it is completely out of the question that it should be considered a material object of value.” (Author’s translation.)

16 Addendum to the joint Last Will of 1 July 1930: “In order to ensure the continued existence of our joint collection, which we wish to transfer to public ownership, we simultaneously created financial means for funding the foundation, which is to be tied to a transfer of the collection into public ownership.” (Author’s translation.)

17 Katharina Flach. Letter to Dr. Ulrich Weitz dated 6 February 1981.

18 Letter from Robert Diels, Geheimes Staatspolizeiamt to the Prussian Minister of the Interior dated 25 October 1933, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Akten des Preußischen Finanzministeriums, I HA Rep. 151 IA Nr. 8070; Blatt 79 (author’s translation).

19 Letter from the Zehlendorf tax office to Eduard and Margarete Fuchs dated 24 February 1937: Reich Flight Tax assessment of 29,552 RM, Fuchs Exile Estate, Stanford University, Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. Nicolaevsky Collection, Series no. 264, box 618, folder 9.

20 https://www.kulturgutverluste.de/Webs/DE/Forschungsfoerderung/Projektfoerderung-Bereich-NS-Raubgut/Privatpersonen/Index.html (last accessed: 25 September 2020).

21 Landesarchiv Berlin: A Rep. 243-04. Reichskammer für bildende Künste, Landesleitung Berlin, vol. 29.

22 http://www.lostart.de/Webs/EN/Datenbank/Suche/SucheMeldungSimpel.html?resourceId=7410&input_=45732&pageLocale=en&simpel=Roof+Rider+Fuchs&type=Simpel&suche_typ=MeldungSimpel&suche_typ.HASH=5636e3666350271723a0&suchen=Search (last accessed: 25. September 2020).

23 http://www.smbdigital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=direct/1/ResultLightboxView/result.t1.collection_lightbox.$TspTitleImageLink.link&sp=10&sp=Scollection&sp=SfieldValue&sp=0&sp=0&sp=3&sp=Slightbox_3x4&sp=0&sp=Sdetail&sp=0&sp=F&sp=T&sp=1 (last accessed: 25 September 2020).

24 Eduard Fuchs, Dachreiter (München: Langen, 1924), 30f (author’s translation).

25 Letter Konzentration AG to the Prussian Ministry of Finance, 16 June 1934, Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin Akten des Preußischen Finanzministeriums: I HA Rep. 151 IA Nr. 8070, Blatt 231-232.

26 See: Gabriele Anderl, Chronik einer Obsession. Die Geschichte der Asiatika-Sammlung Exner (Wien: Czernin Verlag, 2012); Anton Exner, in: Lexikon der österreichischen Provenienzforschung, forthcoming (https://www.lexikon-provenienzforschung.org/exner-anton (accessed: 07 October 2020)).