ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Jörn Grabowski

ABSTRACT

Based on sources in the Berlin state museums’ Central Archive, the article describes the complex route to acquisition of a striking painting which had been on loan to the National Gallery in East Berlin since 1958. It was a focal point of the permanent exhibition and visitors perceived it as a permanent fixture of the collection. The acquisition was compounded by the Cold War and the financial difficulties of an East German institution needing to settle with a London-based vendor in hard currency. The tortuous process took almost three decades and is documented in unusual detail in the museum archive. With hindsight, the museum took a justifiable decision in favour of unprecedented steps to acquire a highlight of its collection.

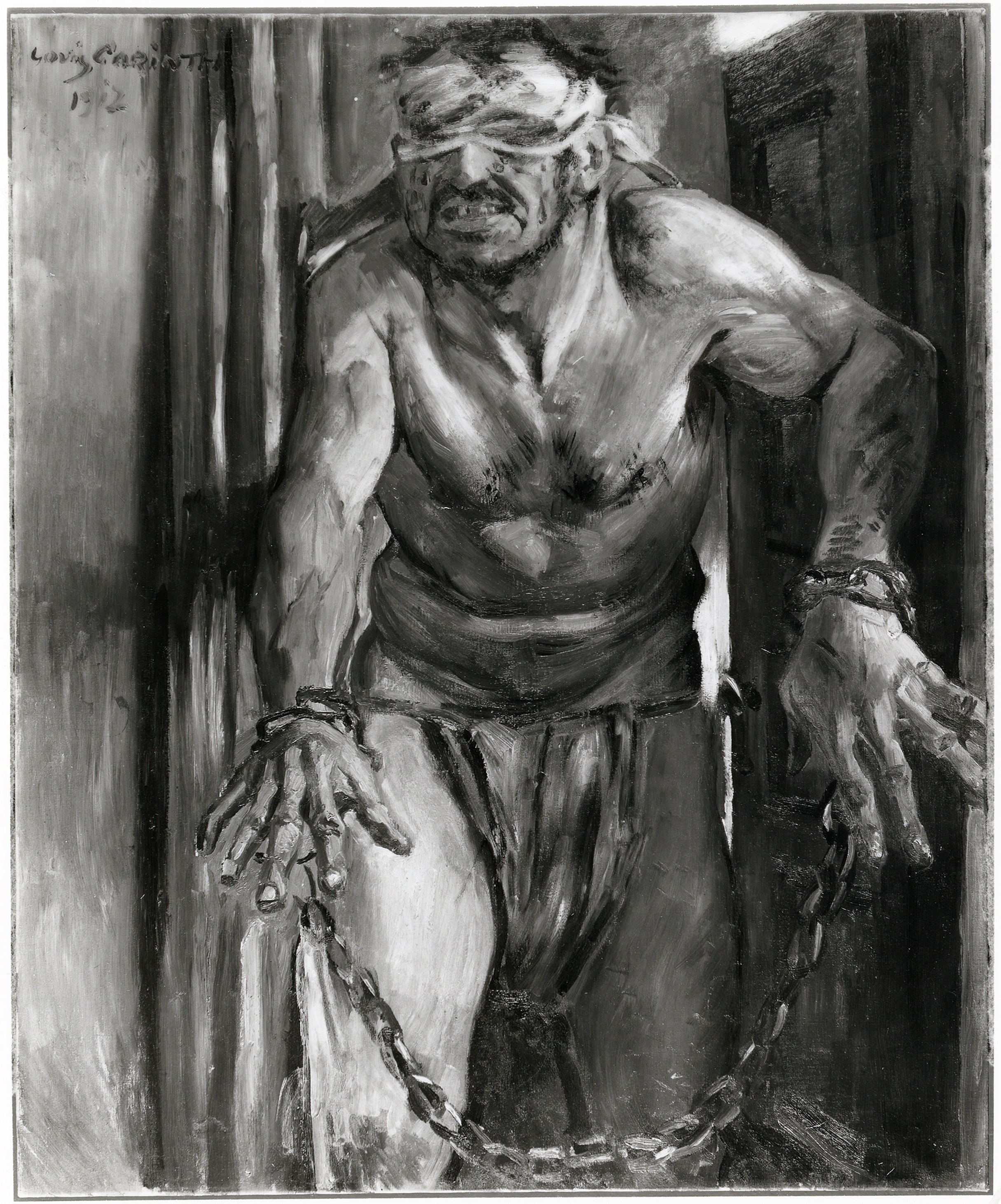

When in March 1979 a letter posted in London arrived in the office of the director general of the Berlin state museums, an umbrella administration for a number of cultural institutions in East Berlin, a situation which had remained static in the National Gallery for a number of years began to shift fundamentally: Mrs Carlotta Kenmore offered the painting Samson Blinded created in 1912 by Lovis Corinth (fig. 1) for sale to the museum.1 For personal reasons, she argued that she could no longer leave the painting on loan to the National Gallery, where it had been since May 1958, and she asked director Eberhard Bartke to propose a suitable process of acquisition for the painting in “freely convertible foreign currency”. If this proved unworkable, she would find herself constrained to take the picture back and offer it for sale at an international auction.2

Fig. 1: Lovis Corinth, Samson Blinded, 1912, oil on canvas,

inv. no. A III 668. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie /

Andres Kilger

Eberhard Bartke had only held the double role of director general and director of the National Gallery for three years. He took stock of the situation: the painting had been in the museum for a full twenty-one years. Not only did the continuous presence of Samson Blinded raise the profile of the already meagre Corinth collection in East Berlin’s National Gallery, the picture had also become an indispensable part of the permanent exhibition of the main gallery, and it was perceived by visitors as integral to the museum’s holdings.

The following article will outline the tortuous path of the ultimate acquisition of this painting, based on archival sources in the Central Archive. The earliest document mentioning the painting with regard to a potential acquisition for the National Gallery dates from 1954. William Kenmore, who had changed his name from Willi Kahnheimer, was a former banker and now director of the London-based company “Roditi International Corporation”. He visited Paul Ortwin Rave, responsible for the National Gallery in West Berlin, on 1 July 1954 to offer his painting for sale.3 The back of the visiting card Kenmore offered in the meeting bears the following note: “Offer Corinth Blinding of Samson \ 2000 (1500?) DM \ Vis. on 1 July 1954 \ Corinth Exhibit. NG 1926, no. 219 \ (Kahnheimer), 1912”.4

Corinth’s painting Samson Blinded had already been in the Berlin National Gallery for short periods of time in 1923 and 1926. At the time, the director Ludwig Justi considered it worthy of being shown on the occasion of the artist’s sixty-fifth birthday in the rooms of the former Crown Prince’s Palace. He displayed it again three years later in a commemorative exhibition in honour of Lovis Corinth.5 In spite of this history and the low asking price of just 2,000 Deutschmarks, which Paul Ortwin Rave intended to negotiate down to 1,500, the museum’s expert committee did not vote in favour of the purchase. Rave expressed his regrets when he informed William Kenmore of the decision. At the same time, he was hopeful that another opportunity might come at a later date, “to come back to the matter [...] should you still own the picture”.6 Time would prove Paul Ortwin Rave right.

Four years later, in the spring of 1958, the National Gallery was once again offered to purchase Samson Blinded. The Berlin state senator for education, Joachim Tiburtius, conveyed William Kenmore’s intention of selling his Corinth to Leopold Reidemeister, new director of the former State Museums and director of the National Gallery.7 Since the (short-lived) sister institution “Twentieth-Century Gallery” was not interested, Tiburtius asked Reidemeister to consider whether the Corinth might be of interest to him.8 Leopold Reidemeister declined politely but firmly.

His reasons are likely tied to his museum’s relatively rich holdings of works by this Berlin Secession artist. Even taking into consideration the losses caused by the “Degenerate Art” seizures by the National Socialists in 1937 (when twelve paintings and five works on paper were taken),9 the West Berlin National Gallery disposed of a total of nine works by Corinth, taking into account returns from depots, repurchases and new acquisitions.10 The National Gallery was not interested in buying another one.

William Kenmore was forced to recalibrate. Since he could not sell his painting in the Western part of the city, he turned to the state-sponsored art trade organisation of the GDR, which took the painting in and placed it on loan to the East Berlin National Gallery.11

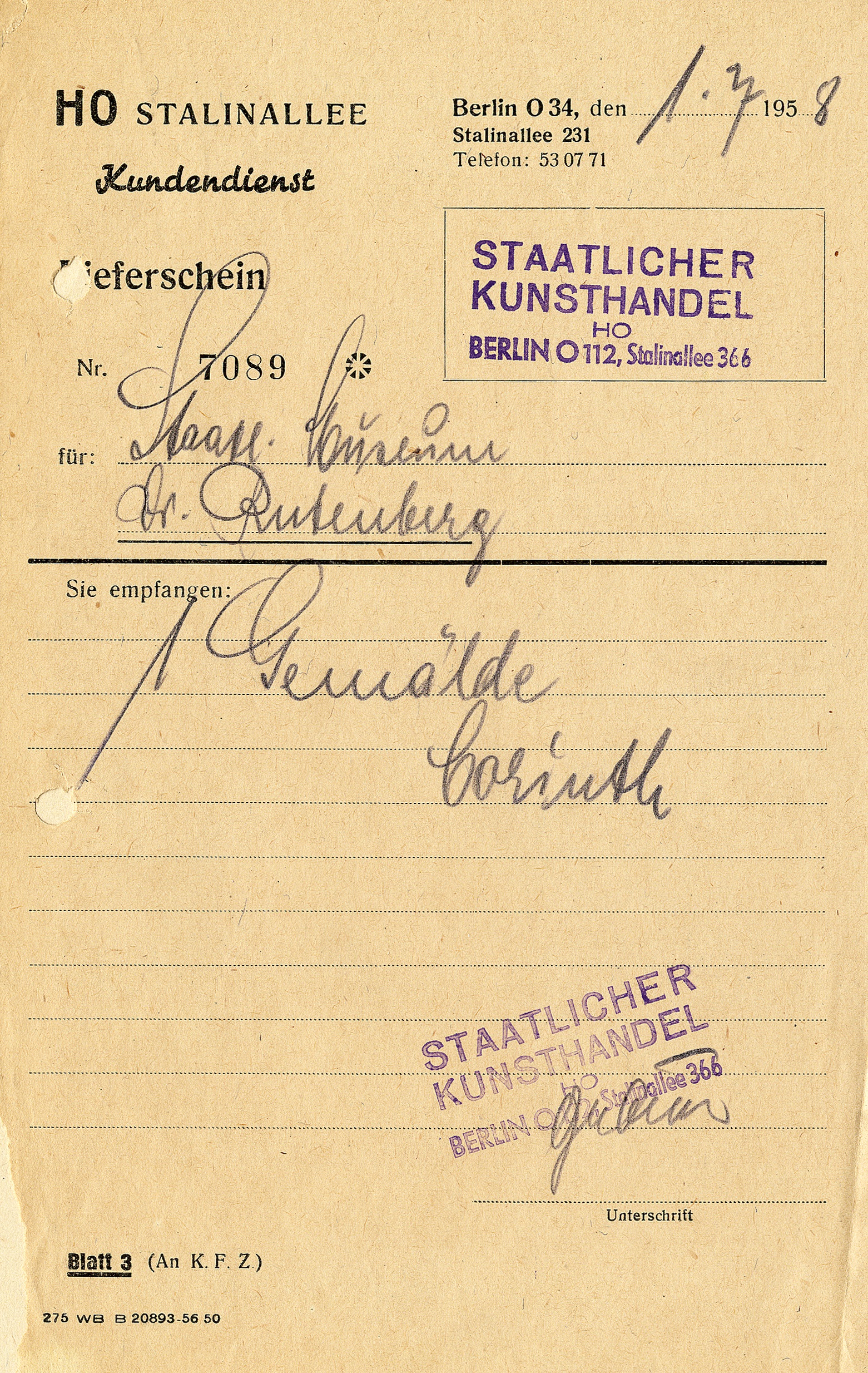

In preparation for the Lovis Corinth exhibition organised by the National Gallery on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the artist’s birth, scheduled from 21 July to 30 September 1958, the painting entered the gallery. A transport bill by the GDR art trade organisation (fig.2) confirms delivery of the picture on 1 July 1958.12 At the end of the year, the organisation offered the loaned painting to the National Gallery “permanently”. It is remarkable that the proposal did not involve a sale but rather an exchange. The East Berlin museums were asked to offer the trading organisation “either one painting or two, which represent a genuine equivalent in return for the work by Lovis Corinth”.13

At the same time, photos of potential works for the exchange were requested in order to start negotiations with the – still anonymous – “owner of the painting”. The exchange had been initiated by Kenmore, it seems, who may have felt that his highly expressive picture was more suited for a public gallery than a private collection. With this consideration, and bearing in mind the previous failed sale attempts, he had agreed to an exchange. Vera Ruthenberg, acting director of the East Berlin National Gallery at the time, was intrigued but had to admit that she was unable to present appropriate objects for exchange on the basis of current museum holdings, since the return of painting from the USSR was not yet complete. As we now know, the partial return of artworks confiscated by the Red Army in 1945/46 and subsequently taken to the USSR to the Berlin museums took place in 1959. At that point Ruthenberg was not in a position to have a full overview of the returns and therefore disposable artworks. She therefore returned the exchange request, as it were, and asked whether it might not be possible to supply artworks or indeed other cultural objects through the trading organisation for exchange.14

Fig. 2: Receipt, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv (SMB-ZA, II A/NG 516)

Almost half a year later – and following further negotiations with Kenmore – the art trade organisation approached the National Gallery again. This time, the information given to Ruthenberg was somewhat clearer and more explanatory: she was told that the owner of the picture was “Mr Kenmore at the firm The Roditi International Corporation Ltd, London”, and that after consultation he had agreed to part with the picture for 20,000 Deutschmarks. However, Kenmore, who worked as an agent for East German optical instruments in the UK and had a good relationship with the company Zeiß/Jena, had expressed a desire to obtain optical devices of an equivalent value for the painting. He would not accept any other settlement.15 Since the asking price of 20,000 Deutschmarks was considered justified on the basis of prices achieved on the international art market, it was suggested that Dr Ruthenberg contact the Ministry of Culture with regard to this accounting matter, in order to find a way via the Ministry for Light Industries to offer Mr Kenmore equivalent compensation through optical instruments through establishing clearing units. For the National Gallery, this was a new and promising variant. It would dispense with the need to obtain foreign currency, an undertaking that was generally considered at least difficult, if not impossible. In addition, there was no need to worry about deaccessioning of artworks. Everything considered, this was an auspicious start of the unexpected acquisition campaign.

Ruthenberg promptly informed the director general and the museum administration about the object to acquire and the proposed sale conditions. She emphasized the particular artistic value of the oil painting measuring 129 x 105 cm, depicting the Old Testament figure of Samson, bound with a blood-soaked cloth covering his eyes. Samson’s hair had been cut off, robbing him of his superhuman strength, so that the Philistines could overpower, blind, and chain him. The work was regarded as one of the most poignant artistic expressions by Corinth. Since it had been created directly after the artist’s stroke, the tortured figure was thought to visualize autobiographical elements pointing to the master’s own condition. In view of a Corinth collection that was much reduced by National Socialism and war, the National Gallery would benefit exceptionally from the acquisition. Unlike the National Gallery in the Western part of the city, the East Berlin gallery only possessed a meagre four paintings.16 The division of Berlin imposed by the Cold War and the resulting impossibility of reuniting the artworks from Berlin museums dispersed by the war had led to this imbalance of holdings. For the staff of the East Berlin National Gallery, the acquisition of this significant painting in particular presented a welcome remedy to Corinth’s Ecce Homo, painted in 1925 and seized in the “Degenerate Art” purge, a picture that was considered irretrievably lost and now located in the Kunstmuseum in Basel. Great expectations thus rested on Samson Blinded.

Ruthenberg initiated all necessary steps at her disposal. Based on the information by the director general Gerhard Rudolf Meyer17, the request for acquisition was passed to the Ministry of Culture, which had previously merely stated that the ministry “had not received a formal request for a Corinth purchase” and that the National Gallery would have to fund the acquisition “from its own acquisition budget as a matter of course”.18 Since the enquiry about funding the painting’s acquisition either through clearing units in the form of optical devices or through payment in foreign currency had not been answered, the only way forward was to procrastinate. Ruthenberg assured the state art trade organisation that the National Gallery was still keenly interested in acquiring the object, but that a purchase could not be realized in the year 1959. After just over six months, in September 1960, she made a renewed attempt via the state art trade organisation to move the acquisition matter forward. This was prompted by an offer for sale of a painting by Richard Parkes Bonington to the gallery from a private collection. Since a purchase was ruled out, Vera Ruthenberg thought of the owner of the Corinth who might be interested in such a painting, offering an opportunity to the National Gallery to at least part fund an acquisition of Samson Blinded.19 Archival sources do not reveal whether the GDR art trade organisation took up Ruthenberg’s suggestion to view the Bonington in the National Gallery. Samson Blinded thus remained on loan from the organisation in the National Gallery’s permanent exhibition.

Another four years would pass before a new attempt was made in the acquisition matter. Following an enquiry by the art trade, the Ministry of Culture, Department for Fine Arts and Museums – section museums, monument preservation, turned to the National Gallery with a suggestion. Were the gallery still keen on acquiring the Corinth, it was to contact the state-owned trade organisation for modern art (Volkseigener Handel Moderne Kunst)20 directly. The latter would then “clarify with the relevant state organs whether payment in terms of the earlier agreement”21 would still be feasible. A purchase via clearing units that had been considered years ago, that is an exchange against optical instruments, seems to have become pertinent once more. Yet in 1964, as before, neither was the required foreign currency available nor could an exchange be effected, and hopes were dashed yet again. Everything remained the same – the painting continued to hang for another six years on loan in the National Gallery.

It was only in 1970 that a gradual change in the acquisition history appeared on the horizon, even though no final decision was reached. The owner William Kenmore now demanded that his picture be returned. Through his GDR partner, the state art trade organisation, he informed the National Gallery that he had decided to sell the picture and requested that it be returned to him.22 Quick decisions were now required. The correspondence from previous years was extracted from the archives and passed into official channels with renewed applications. Willi Geismeier,23 director of the National Gallery since 1966, informed director-general Gerhard Rudolf Meyer about the current situation and advised that a decision by the ministry of culture was to be requested “post-haste”. Geismeir presented the following plan: since years ago, the option of acquisition via clearing units had not been approved, only two possibilities currently remained for the acquisition of this major work by the artist. Either the state budget should offer the requisite foreign currency, or the National Gallery would need to fund the acquisition of Samson Blinded through “the sale of some works via the state art trade organisation”.24 In any case, a fundamental decision was required whether the painting should be acquired or not. Accordingly, a request from the director-general was dispatched to the ministry of culture, conveying the remarks that in view of the outstanding importance of Lovis Corinth and the exceptional artistic rank of Samson Blinded it was hardly justifiable that “this painting should leave the GDR”. However, either would foreign currency need to be granted, or “a sale of disposable paintings from the National Gallery’s depot via the state art trade organisation be allowed”.25 Within only three days, a positive response was received. The minister shared the view that the work should ideally remain in the GDR and demanded a careful enquiry about the level and acceptability of the asking price, as well as details of paintings which could conceivably be offered for sale.26 A decision had been made – Samson Blinded could be acquired through deaccessioning works in the depot.

Two questions remained to clarify: firstly, direct contact with William Kenmore needed to be established to ask whether he was essentially willing to sell the painting to the National Gallery, and at what price. Furthermore, the National Gallery needed to research the price level for the Corinth in order to be prepared for potential negotiations. Lothar Brauner,27 long-term research associate at the National Gallery, was tasked with relevant research and with scheduling appointments with the state art trading organisation to “launch initiatives”. The situation was slightly convoluted by Kenmore’s wish of involving a specialist from “West Germany” who could comment on the value of the painting as a basis for further negotiations. As he himself stated, he was unaware of the picture’s value and he only recalled that he “paid GPP 1,500 for it in 1920”.28 The National Gallery argued against the involvement of a valuer since he would also simply be able to orientate himself at available auction prices.These prices were typically determined by art auctions which in turn depended on the respective selling and buying circumstances and only increased by bidding. In addition, the particular and unique qualities of Samson Blinded needed to be taken into account, as the picture was a true museum piece and hardly suitable for a private residence. Therefore, one would prefer to come to an agreement without involving a third party. Willi Geismeier enclosed a long list of Corinth prices from the last twelve years with his letter, as extracted from the volumes of the Munich Art Price Index. Based on the original asking price from 1959 of 20,000 Deutschmarks and considering the selling prices of recent years, Kenmore was offered a purchase price of 60,000 Marks.29

Yet these tactical variables would prove to be irrelevant. According to a report by Willi Geismeier, there was an opportunity at the Leipzig trade fair to meet with William Kenmore in person, and on this occasion he declared that he did not wish to sell the picture after all. Nevertheless, he was willing to leave it on loan to the National Gallery, “since due to his long-standing excellent business relations to the GDR he would rather see it there than in a West German museum”.30 At the same time, Kenmore alluded to a possibility of letting the gallery have the picture “in a different way” in connection with business negotiations. He did not divulge any steps or options he considered in this context. Still, the desire to sell the picture through offsetting commercial goods is again implied here. It was finally agreed that the loan situation would change by dissolving the contract with the art trade organisation and by signing a new loan agreement with the National Gallery. Apart from the usual general conditions such as an appropriate notice period and insurance sum, the National Gallery also received a right of first refusal. As agreed, the loan agreement was set up at the end of March 1971 and signed by Carlotta and William Kenmore. The insurance value had been set at 60,000 Marks, in accordance with a recommendation by the National Gallery. In this way, the matter came to a close, for the time being. The painting remained in the National Gallery, this time with an “in-house” loan agreement and with the right of first refusal for the future.

Two years later, the lender died and shortly afterwards, at the end of May 1973, his son Stephen Kenmore visited the National Gallery. On behalf of his mother he informed the museum that she would not change the terms of the loan, with the exception of the insurance value. The painting could remain in the Gallery as a sale was not envisaged at the time. Soon afterwards, an amended version of the loan agreement arrived at the National Gallery, with the added address of the son as lender and also a considerable increase in insurance value to 100,000 Marks. A much more sensitive issue was the cancellation of the National Gallery’s first right of refusal, which had not been discussed during the son’s visit. This raised the risk of still losing the supposedly secure object. When asked, Mrs Kenmore explained that she had informed herself in the meantime about the value of the picture and considered putting it up for auction at a sale in the Federal Republic. However, should the National Gallery still want to purchase the painting she was expecting an offer pursuant.31 Now the ministry would have to clarify the situation with regard to foreign currency as quickly as possible. Based on the insurance value of 100,000 Marks, Willi Geismeier expected a much higher asking price in line with international market values and consequently foresaw a need to raise a ceiling price of 200,000 Marks. He considered this sum to be appropriate, especially as such a high value picture would not appear on the international art market again. For GDR museum holdings, the acquisition of this important work would be highly desirable, and the picture would be an exceptional enhancement of the National Gallery’s collection.32 The ministry’s negative response did not lead to any further action to begin with, since Mrs Kenmore declared four days later, to everybody’s surprise, that “the entire matter had lost its urgency” and consequently “everything would remain as is”.33 Nevertheless, the fundamental question whether foreign currency could be made available in general or not needed to be addressed. A year later, Willi Geismeier renewed his application and now received a response from the director general’s office that the situation had not changed and that the ministry was not in a position to provide the funds, which was to be considered final.34 The situation would remain static for another four years.

In March 1979, Mrs Kenmore informed the director general that for personal reasons she was no longer able to leave the painting on loan to the GDR on the basis of the previous agreement. She requested a proposal of how to move forward. If the museums were “unable to agree to payment in freely convertible currency of a yet to be determined price”, she would be forced to withdraw the picture and offer it for sale at an international art auction.35 This time, Mrs Kenmore’s intention seemed final, especially as she had appointed an authorized representative, the head of the Berlin office of the company Carl Zeiss Jena, to be available for further and now urgent negotiations. The latter now also informed the National Gallery that the painting was offered at an acquisition price of 150,000 Deutschmarks, and that the Kenmore family insisted on concluding the matter before the end of the current year 1979. Immediate action was needed. The matter was to be resolved at a pivotal level in coordination between the ministry for culture and the ministry for foreign trade. As chairman of the national Kunstschutz-Kommission, the “art protection committee”, Eberhard Bartke was to schedule a discussion with Horst Schuster, the head of the state-owned art dealing organisation Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH. The following issues were on the agenda: first, a proposal to involve the Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH in the work of the Kunstschutz-Kommission. For this purpose, a suitably experienced employee of the Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH would join the committee. Furthermore, it was agreed that the holdings of the Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH be inspected at regular intervals by experts of the Kunstschutz-Kommission, in order to prevent artworks from leaving the GDR that would be irretrievable losses for the country. The state art trade organisation would be charged with the monetary settlement for the acquisition of such objects by the museums from the ownership of the state art trade organisation. In turn, a value equivalent for the resulting Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH’s loss of foreign currency would be provided by sourcing additional saleable objects from the art trade as well as from the holdings of GDR museums [sic!]. Second, it was agreed that the state museums in East Berlin would provide exportable artworks in its care at a value level of 300,000 Deutschmarks, in accordance with the Ministry of Culture, in order to acquire the Lovis Corinth for 150,000 Deutschmarks before the end of the current year 1979.36 In return for allowing its stock to be inspected and guaranteeing to sell valuable artworks to the museums, the ministry of foreign trade and its department for commercial coordination with its subsidiary, the Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH, were promised a substantial increase in exportable art objects from the art trade and from the museums. In view of this complex agreement and the concessions it involved, the acquisition of the Corinth had become feasible for the National Gallery. At the beginning of 1980, director general Eberhard Bartke received the decisive message.37 At the ministry for foreign trade, a meeting on 29 December 1979 about the purchase of Samson Blinded had produced the following decisions: the required foreign currency amounting to 150,000 Deutschmarks would be made available, so that the necessary contracts could be drawn up and the purchase of Samson Blinded be effected through the Kunst- und Antiquitäten GmbH. At the same time, the state museums in East Berlin were tasked with providing the art trade organisation with “circa 2 objects from the holdings of the state museums in Berlin at a value of circa 170k Marks in return”. The upside of roughly fifteen percent was described as “an amicable starting point” that would be acceptable. At the same time, it was emphasized that the “return” should not be composed of a large number of individual objects but needed to consist of two artworks valued at the required amount. In addition, it was once again reaffirmed in principle that “it was certainly justifiable that something would be removed from the museum holdings, since another art asset would in return become the property of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin”.38 Taking into account the necessity of providing foreign currency for “our republic”, the ministry also did not raise objections should the equivalent value for Samson Blinded be raised from 170k to 180k. In all this, it was important to bear in mind that “good and cooperative collaboration would be developed” between museum staff and the employees of the art trading organisation.39 This amounted to an indirect request to accept the sale of museum-owned pieces, or at least take a sympathetic stance. In practice, the acquisition of Samson Blinded took place as follows: the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH purchased the work from its current owners with its own funds on behalf of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The art trade organisation then resold it to the state museums in GDR marks at an exchange rate of 1:1. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin supplied paintings for sale in the non-Socialist economic territory (commonly referred to by the German acronym NSW) with the objective of raising the sum of 170,000 Deutschmarks. The sale was effected through consignments at auction abroad, for which minimum prices were set in conjunction with the museum employees, in turn forming the basis for achieving the sum of 170,000 Deutschmarks.

Now the National Gallery was faced with the problem of selecting one or two artworks at the required value level for exchange. This would prove especially difficult, since the previous assumption had been based on an offer of several objects from the depot. The target were artworks that could neither be regarded as gallery pieces nor as scholarly valuable collection components of an oeuvre. One solution seemed to be offered by the deaccession of a second cast of Auguste Rodin’s Age of Bronze (fig. 3). Since the version that had been in the National Gallery since 1903 had returned from the Soviet Union in 1958 and the superfluous second cast was on permanent loan to the sculpture collection of the state museums in Dresden, the curator Lothar Brauner felt that a deaccession was conceivable. As this was a real duplicate, neither the National Gallery nor the national art holdings of the GDR would suffer a real loss, especially as further bronze casts were in the collections in Weimar and Altenburg. Brauner valued the piece in Dresden fairly high, considering a recent sale in France of another copy of The Age of Bronze for the equivalent of 300,000 Deutschmarks. At least, the required value of 150,000 Deutschmarks for the Corinth seemed achievable. As a collegiate measure, he recommended to offer first refusal to the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, of course contingent on “supplying artworks for sale at a foreign currency value level of 150,000 Deutschmarks plus potential interest payable on credit”.40

In this instance, the Dresden state museum would have been handed the difficult task of selecting artworks for deaccessioning. But the delicate issue became redundant when faced with the difficult provenance of the bronze cast in question, which had come from the former Krebs collection in Holzdorf near Weimar, where it had been expropriated in the course of the “land reform” and later passed to the National Gallery. Brauner acknowledged that this provenance could give rise to “different ideas of ownership between the two German states”, which might need clarification.41 The proposal was withdrawn and taken off the table. It became necessary to consider relinquishing a larger number of objects. The National Gallery staff selected several paintings which were recommended for official release to the ministry of culture and then handed over to the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH for auction sale abroad.

The proposal concerned four paintings: Eduard Magnus’ portrait Frau Rechtsanwalt Lau, Wilhelm Riefstahl’s All Souls Day in Bregenz, George William Joy’s Truth, and William Shade’s Spring of Love.42 In his assessment to argue the dispensability of these works, Brauner stated that they were all relatively early acquisitions by the National Gallery, which held in all cases four or five other works by the same artists, so that the loss would not be severely felt.

Fig. 3: Auguste Rodin, The Age of Bronze, 1875/76. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,

Nationalgalerie. Photo by Andres Kilger.

Nevertheless, George William Joy’s Truth was a unique work which had been acquired at Berlin’s Internationale Kunstausstellung in 1896 with annual surplus funds from the Academy. It had never been intended for the museum but for permanent loan to provincial museums. For the three other works, their last appearance in the collection catalogue was mentioned (Magnus 1923, Riefstahl 1921, Shade 1903) to show their lesser importance as demonstrated by their omission from later reprints of the collection catalogue. With regard to Spring of Love, the assessment states: it “appeals to the taste generated by the so-called wave of nostalgia in wide circles of the bourgeois public”.43 There was a sense of relative confidence in having catered to the “taste” of the targeted circles of society. Director general Bartke also expressed optimism with regard to the monetization of the selected pictures. “With regard to prices, I think that the paintings should realize proceeds of 170,000 Deutschmarks.”44 He cautiously added that if necessary, a further picture could be supplied. And indeed, this would later prove essential.

The sale contract signed by Carlotta Kenmore on 5 February 1980 was countersigned on 21 February 1980 on behalf of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin by the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH. When the purchase price was received on 11 March 1980, the picture finally became the property of the state museums in East Berlin.45 It was inventoried three days later under no. A III 668. Now it only remained for the museums to pay the bill via art deaccessions at auction in the West. In the trade press, the unique event prompted an advertisement in the West German magazine Weltkunst. The auction entitled “Important European Paintings from the 19th and 20th Centuries” at Christie’s in London on 20 July 1980 was even announced in a two-page spread in the magazine.46 On the right side, the painting All Souls Day in Bregenz by Wilhelm Riefstahl was illustrated with the caption “Property of the Nationalgalerie, East Berlin”. The paragraph underneath outlined the purpose of the sale, in that the East Berlin National Gallery needed to raise funds for the acquisition of Samson Blinded by Lovis Corinth.47

However, the desired success failed to materialize. The expected sum of 170,000 Deutschmarks was nowhere near being achieved. There were numerous press reports on the inadequate outcome of the auction sale. The painting All Souls Day by Wilhelm Riefstahl and the portrait Frau Rechtsanwalt Lau by Eduard Magnus only realized 10,500 pounds (circa 44,000 DM). The third picture, Spring of Love by William Shade, which had raised great hopes due to the “wave of nostalgia in wide bourgeois circles” even remained unsold below the reserve price.48 The exceptional event, where the GDR had offered paintings from the East Berlin National Gallery for sale at Christie’s in London for the first time, was reflected in the press. Christie’s annual Review of the Season reflected upon the unusual East-West constellation with the following colourful description:

The somewhat sinister approach to Checkpoint Charlie in Berlin would not normally be thought of as an avenue to the commercial fine art world, but it was in this direction – from West to East – that various members of Christie’s have been travelling during the last year. [...] Christie’s have established excellent and business-like relations with East German authorities, and it is hoped that this new development may lead to further sales on the sensible pattern which the National Gallery has established for the acquisition of new material.49

The fourth deaccessioned painting Truth by George William Joy was offered later in the auction of “Important Victorian Pictures” on 24 October 1980 and sold for 7,000 pounds.50 William Shade’s Spring of Love which had remained unsold in June 1980 was reoffered on 20 March 1981 and found a new owner for only 1,000 pounds.51 The resulting accounts were of corresponding meagre proportions. The settlement statement by the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH after the first sale arrived at a net result of 34,026 VM (Valutamark) after deductions of expenses, Christie’s vendor’s commission, insurance, taxes and shipping from the gross sum of 10,500 pounds.52 The settlement statement for all four paintings offered in 1980 arrived at a net total of 69,408.21 Deutschmarks. That was only circa 40% of the purchase sum plus commission dispersed by the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH for the Lovis Corinth, which amounted to 172,500 Deutschmarks. A further 103,091.79 Deutschmarks remained to be settled through further artworks.

A second selection was made. It comprised the Portrait of a Young Lady by Eugen von Blaas and a Winter Landscape with Horse-drawn Carriage by Ludwig Munthe. Both works had entered the National Gallery in 1914 as part of a bequest of the entire collection of Dr Georg August Freund, a Berlin gentleman of independent means. In addition, a Portrait of Bismarck by Franz von Lenbach was selected, which had returned to the gallery from the Soviet Union in 1958. Even though the collection of the National Gallery already held several portraits of the former Reich Chancellor and may have done without this one, it was withdrawn on instruction from the ministry of culture. There are no sources currently available which would give a reason for the decision. It could have been related to the picture’s unclear provenance – it used to hang in the Reich Chancellery, origin unknown – or it was perhaps not considered appropriate after all to sell off at auction, from East to West, an image of the politician who paved the way for the German Empire.

As in the first selection, the disposability of the works was ensured due to their lesser quality and resulting minor importance for the National Gallery collection. Also, all pictures were not known to the public since they had not appeared in the catalogues of the National Gallery to date.53 Nothing therefore stood in the way of deaccessioning the two paintings by Eugen von Blaas and Ludwig Munthe. The proceeds achieved were slightly more advantageous, especially since the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH had decided to either sell the works on commission directly to the highest offer, or to pass to a gallery for auction. The reserve prices were achieved (Winter landscape by Munthe at 30,000 Deutschmarks and De Blaas’ female portrait at 20,000 Deutschmarks), and even surpassed by 10,000 Deutschmarks. This left the National Gallery with an outstanding amount of 43,091.79 Deutschmarks.

As Geismeier noted in longhand on the invoice, “a new (hopefully final) selection” would need to be made.54 In the tried and tested format, two further paintings were accordingly handed over to the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH six months later. The reserve prices set for Otto Günther’s Woman with a Candle in a Wine Cellar and William H. Bartlett’s Sheep Wash in a River at 15,000 and 25,000 Deutschmarks would prove to be realistic. Both paintings were sold for a total of 40,425 Deutschmarks, so that a remainder of 2,667 Deutschmarks would need to be settled by the National Gallery through supplying further paintings in order to achieve the objective of concluding the process in the current calendar year.55

Yet even the fourth selection of works took its time, so that another delivery of two small Autumn Landscapes I and II by R. Ducat and a Mountain Landscape by R. Molena only arrived in July 1983. The settlement from December of the same year listed a sale price of 850 Deutschmarks each for the Autumn landscapes I and II and 1,800 Deutschmarks for the Mountain Landscape. The total of 3,500 Deutschmarks left a profit for the National Gallery of 833 Deutschmarks.56

The acquisition of Samson Blinded certainly ranks among the most lengthy and also most complex purchase histories in the Berlin National Gallery. The related files in the Central Archive of the Berlin state museums cover a timespan of twenty-nine years. Twelve archival units comprise a multitude of documents,57 providing detailed insight in the process adopted at the time.

After the West Berlin National Gallery had declined to acquire the picture in 1954, the work entered the East Berlin National Gallery, first on loan from the GDR’s state art trade organisation, later as a long-term loan from the Kenmore family in London. After an extended acquisition process, the museum was finally able to conclude the purchase of the painting in 1983 with payment of the final instalment.

The predicament of having to find freely convertible Deutschmarks for the purchase created particular challenges. In the absence of a disposable sum in foreign currency, there was only one option, which had never been tried: deaccessioning disposable artworks from the museums’ own stock. From today’s perspective, the extraordinary importance of the object entirely justifies the circumvention of fundamental concerns preventing any deaccessioning of artworks in public ownership. What was then a “somewhat undervalued” picture, as Lothar Brauner wrote to the artist’s son Thomas Corinth in 1982, became one of the most important acquisitions in the history of the National Gallery in East Berlin.58

|

Pos. |

Sale Date |

Artist |

Title/Date |

Inv.no. |

Proceeds in DM |

|

01 |

20 June 1980 |

Eduard Magnus |

Portrait Frau Rechtsanwalt Lau |

A I 389 |

1,777.16 |

|

02 |

20 June 1980 |

Wilhelm Riefstahl |

All Souls Day in Bregenz, 1869 |

A I 203 |

35,543.26 |

|

03 |

24 October 1980 |

George W. Joy |

Truth |

A I 688 |

28,073.14 |

|

04 |

20 March 1981 |

William Shade |

Spring of Love, 1881 |

A I 333 |

4,014.65 |

|

05 |

21 July 1981 |

Eugen de Blaas |

Portrait of a Young Lady |

A III 596 |

20,000.00 |

|

06 |

21 July 1981 |

Ludwig Munthe |

Winter Landscape with Horse-drawn Cart, 1863 |

A III 643 |

40,000.00 |

|

07 |

15 October 1982 |

Otto Günther |

Woman with a Candle in a Wine Cellar, 1882 |

A III 607 |

20,000.00 |

|

08 |

15 October 1982 |

William H. Bartlett |

Sheep Wash in a River, 1894 |

A III 595 |

20,425.00 |

|

09 |

12 December 1983 |

R. Molena |

Mountain Landscape |

A III 709 |

1,800.00 |

|

10 |

12 December 1983 |

R. Ducat |

Autumn Landscape I |

A III 708 |

850.00 |

|

11 |

12 December 1983 |

R. Ducat |

Autumn Landscape II |

A III 708 |

850.00 |

|

173,333.21 |

Jörn Grabowski was head of the Central Archive at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin for 41 years before he retired in 2014.

Translation: Susanne Meyer-Abich

1 This article is published here in English for the first time. It appeared previously as In Ermangelung von Valuta – Kunst gegen Kunst. Zur Erwerbung des »Geblendeten Simson« von Lovis Corinth aus den Quellen des Zentralarchivs der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, in Petra Winter (ed.), Schriften zur Geschichte der Berliner Museen vol. 4, Leitbilder einer Nation (Köln: Böhlau, 2014) 253-271?. The editors of the present publication decided to include a slightly updated version in this issue and make it accessible to a wider public in English due to the unusual relevance of the subject for the context of this issue.

2 Carlotta Kenmore to Eberhard Bartke, 19 March 1979, in: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Zentralarchiv (in the following: SMB-ZA), VA 1136, Bl. 69.

3 Paul Ortwin Rave (1893–1962), since 1922 academic assistant under Ludwig Justi, from 1937 acting head of the Nationalgalerie, in 1945–1950 acting director of the Nationalgalerie and in 1954–1961 director of the West-Berlin Kunstbibliothek.

4 “Angebot Corinth Blendung Simsons \ 2000 (1500?) DM \ Bes. am 1. Juli 1954 \ Corinth-Ausstllg N.G. 1926, Nr. 219 \ (Kahnheimer)‚1912”. The handwritten annotation is probably by Paul Ortwin Rave, in: SMB-ZA, II B/NG 4, Bl. 355.

5 The painting was shown in 1923 in the exhibition “Corinth-Ausstellung. Einhundertsiebenzig Bilder aus Privatbesitz” in the former Royal Prussian residence Kronprinzenpalais in Berlin, catalogue no. 63 as well as in 1926 in the exhibition “Lovis Corinth. Ausstellung von Gemälden und Aquarellen zu seinem Gedächtnis” in the Berlin Nationalgalerie, catalogue no. 219.

6 Paul Ortwin Rave to William Kenmore, 22 September 1954, in: SMB-ZA, II B/NG 4, Bl. 354.

7 Leopold Reidemeister (1900–1987), 1957–1964 director general of the foundation Staatliche Museen Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz and director of the Nationalgalerie.

8 Joachim Tiburtius to Leopold Reidemeister, 24. 02. 1958, in: SMB-ZA, VA 6755, Bl. 110. The Berlin Galerie des 20. Jahrhunderts existed from 1949 to 1968, when its holdings were mostly incorporated into the West Berlin National Gallery.

9 Annegret Janda and Jörn Grabowski, Kunst in Deutschland 1905–1937. Die verlorene Sammlung der Nationalgalerie im ehemaligen Kronprinzen-Palais. Dokumentation. Ausgewählt und zusammengestellt von Annegret Janda und Jörn Grabowski (Berlin: Mann, 1992), 86–92.

10 In 1958 the Nationalgalerie collection owned the following works by Lovis Corinth: Donna Gravida, 1909; Inntal-Landschaft, 1910; Walchensee, 1921; Der Maler Leistikow, 1900; Eleonore von Wilke, 1907; Schlossfreiheit, 1923; Das Trojanische Pferd, 1924; Lotte Roll, 1902; Frau Rosenhagen, 1899; Hans Rosenhagen, 1899, and Die Familie des Malers Fritz Rumpf, 1901.

11 See recently Christin Müller-Wenzel, Der Staatliche Kunsthandel in der DDR - ein Kunstmarkt mit Plan? (Halle: Mitteldeutscher Verlag, 2020).

12 See Staatlicher Kunsthandel. Lieferung des Gemäldes an die Staatlichen Museen, Dr. Ruthenberg, 1 July 1958. Verso a handwritten note: Der geblendete Simson Corinth 1912, in: SMB-ZA, VA 4546. In the exhibition shown at the beginning of the year by the West-Berlin Nationalgalerie in the Knobelsdorff wing of Schloss Charlottenburg from 18 January to 2 March 1958, Samson Blinded had not been on display.

13 Belz, head of the Staatliche Kunsthandel to Vera Ruthenberg, acting head of the Nationalgalerie, 13 December 1958, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 137.

14 Vera Ruthenberg to Belz, Staatlicher Kunsthandel, 22 December 1958, in: ibid., Bl. 136.

15 Belz to Ruthenberg, 05 May 1959, in: ibid., Bl. 135.

16 Mohrenfürst, 1909; Mutterliebe, 1911; Frau mit Rosenhut, 1912, and Bildnis Max Halbe, 1917.

17 Gerhard Rudolf Meyer (1908–1977), director general of the Staatliche Museen Berlin in 1958–1976.

18 Sektorenleiter Walter Heese, department Bildende Kunst und Museen, Sektor Kunstmuseen, Denkmalpflege to Vera Ruthenberg, 1 June 1959, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 129.

19 Ruthenberg to Belz, Staatlicher Kunsthandel, 5 September 1960, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl.124.

20 From 1963: Volkseigener Handel (VEH) Moderne Kunst, before Staatlicher Kunsthandel.

21 Zimmermann, Sektorenleiter of the department Bildende Kunst at the ministry for culture of the GDR to the Nationalgalerie, 24 September 1964, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl.119.

22 William Kenmore to Staatlicher Kunsthandel, copy attached to a letter from the company “Antiquitäten. Ankauf-Verkauf” to the Nationalgalerie, 14 August 1970, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl.110f.

23 Willi Geismeier (1934–2007), 1966–1975 and 1983–1985 Director of the East-Berlin Nationalgalerie.

24 Geismeier to Gerhard Rudolf Meyer, 10 August 1970, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 113.

25 Meyer to Kurt Bork, deputy Minister of Culture, 18 August 1970, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 106.

26 Bork to Meyer, 21 August 1970, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 105.

27 Lothar Brauner (1932–2001), frm 1961 on the academic staff of the Nationalgalerie, in 1991 acting director.

28 See William Kenmore to Harry Goese, 21 October 1970, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 102.

29 See Geismeier to Kenmore, 20 January 1971. The note M 20,000 erroneously refers to GDR Marks, but actually the reference was still Deutschmarks, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 93ff. In view of the subject matter and biographical importance of the work, Lothar Brauner had set the value at 80,000 DM, see ibid., Bl. 100.

30 Willi Geismeier to the director general Gerhard Rudolf Meyer, 16 March 1971, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 92.

31 See Carlotta Kenmore to Willi Geismeier, 13 March 1974, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 79.

32 See Geismeier to the ministry of culture, 4 April 1974, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 77.

33 Carlotta Kenmore to Geismeier, 8 April 1974, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 76.

34 Erik Hühns (1926), Deputy director general in 1973–1979 to Willi Geismeier, 27 March 1975, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 71.

35 Carlotta Kenmore to Eberhard Bartke, 19 March 1979, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 69.

36 See Eberhard Bartke to Werner Rackwitz, deputy minister for culture, 20 June 1979 and the draft letters prepared for Werner Rackwitz to the ministry for foreign trade, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 64–67.

37 See GDR Council of Ministers. Ministry for culture. HA Planung und Finanzen to Eberhard Bartke, 2 January 1980, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 60.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid.

40 Proposal by Lothar Brauner to Eberhard Bartke to release the duplicate of the “Age of Iron” by Auguste Rodin for acquisition of the work by Lovis Corinth, 6 June 1979, in: SMB-ZA, VA 7627, Bl. 1–3.

41 Ibid. The work in question was restituted by the Stiftung Preußischer Kunstbesitz to the heirs in 2008.

42 A detailed list of the deaccessioned artworks can be found at the end of this article.

43 Lothar Brauner, Gutachten zur Aussonderung von vier Gemälden, 20 February 1980, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 46.

44 Eberhard Bartke to Horst Schuster, 21 February 1980, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 44.

45 See purchasing contract, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 35.

46 On the auction sale of the four works by Christie’s see recently Xenia Schiemann, Kunsthandel zwischen Ost und West zu Zeiten des Kalten Krieges: Die Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH der DDR und das Londoner Auktionshaus Christie’s, Master thesis Technische Universität Berlin 2021, 65-74, http://dx.doi.org/10.14279/depositonce-11808.

47 See Weltkunst. Aktuelle Zeitschrift für Kunst und Antiquitäten, vol. 50, no. 11, 1 June 1980, 1625.

48 See ibid., no. 14, 15 July 1980, 1947, Der Tagesspiegel, 22 June 1980 and Frankfurter Rundschau, 23 June 1980; see also: sale catalogue Important Continental Pictures of the 19th and 20th Centuries, 20 July 1980, lots 189–190. I am grateful to Stephanie Tasch for her kind assistance in sourcing the copies of Christie‘s sale catalogues of 20 July 1980, 24 October 1980, and 20. March 1981.

49 See John Herbert, ed., Christie’s Review of the Season 1980 (London: Studio Vista, 1980) in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 5f.

50 See auction catalogue Important Victorian Pictures, Christie’s London, 24 October 1980, lot 51.

51 See auction catalogue Important Continental Pictures of the 19th and 20th Centuries and Pictures of Islamic Interest, Christie’s London, 20 March 1981, lot 93.

52 See settlement statement of the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH, 30 August 1980, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 20.

53 See Lothar Brauner, Gutachten über die Aussonderung von drei Gemälden, 21 January 1981, in: SMB-ZA, VA 1136, Bl. 13–19.

54 See settlement of the Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH, 21 July 1981, in: SMB-ZA, VA 7627, Bl. 33.

55 See ibid., 15 October 1982, in: SMB-ZA, VA 7627, Bl. 44.

56 See ibid., 12 December 1983, in: ibid., Bl. 51.

57 Files in the Central Archive of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin: VA 6755: correspondence of the representative of the director general, Rave, as well as director general Reidemeister with the senator for public education (1957 to 1958); VA 1136: Acquisition of the painting Samson Blinded by Lovis Corinth (1958 to 1981); II A/GD 0101: correspondence of the director general with collection departments, L-Z (1959); VA 8949: Purchases and transfers, acquisition proposals, donations (1967 to 1990); VA 7627: Acquisitions: Purchase resp. exchange of artworks via Kunst und Antiquitäten GmbH, Berlin (1979 to 1987); VA 979: Correspondence (received) with the ministries of culture and foreign affairs, vol.1 (A-J) (1977 to 1984); VA 5593/2: Artworks on loan, part 2: after July 1949 (1949-1980); VA 4546: Exhibition “Lovis Corinth zum 100. Geburtstag” (1958); VA 5597: Acquisitions of paintings (1974-1985); VA 5323: Loan names, loans, card index A-Z (1957 to 1969); II B/NG 4: Reference files of Paul Ortwin Rave, correspondence F-K (1954-1955).

58 Lothar Brauner to Thomas Corinth, 1 July 1982, in: SMB-ZA, II A/NG 327.