ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Birgit Jooss

ABSTRACT

The art dealer firm of Julius Böhler, with offices and affiliated companies in Munich, Lucerne, Berlin, and New York, was a major art dealership in the German-speaking world in the first half of the twentieth century. Its business records, which have been the subject of extended research at the Munich Central Institute for Art History since 2019, demonstrate, among other trade activities, the close working relationship with the director of the Bavarian State Painting Collections Ernst Buchner (1892-1962). They cooperated in numerous exchanges due to the difficulty in obtaining foreign currency for sale transactions. Museum works, some from the Royal Bavarian Collections, thus entered the art trade and are today part of public collections abroad. The article examines the practice of exchanges driven partly by political motives during the National Socialist era and gives an insight into the close cooperation between museums and the art trade in the first decades of the twentieth century, and traces the path of two Old Masters to the present as examples of such transactions.

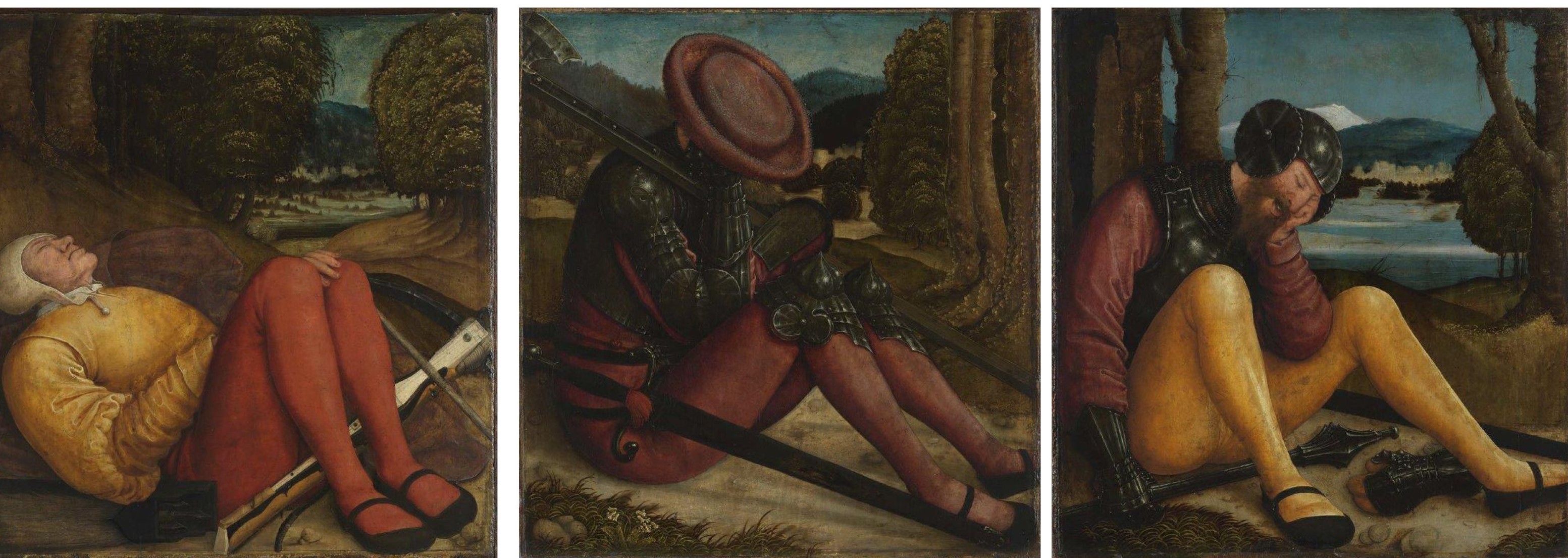

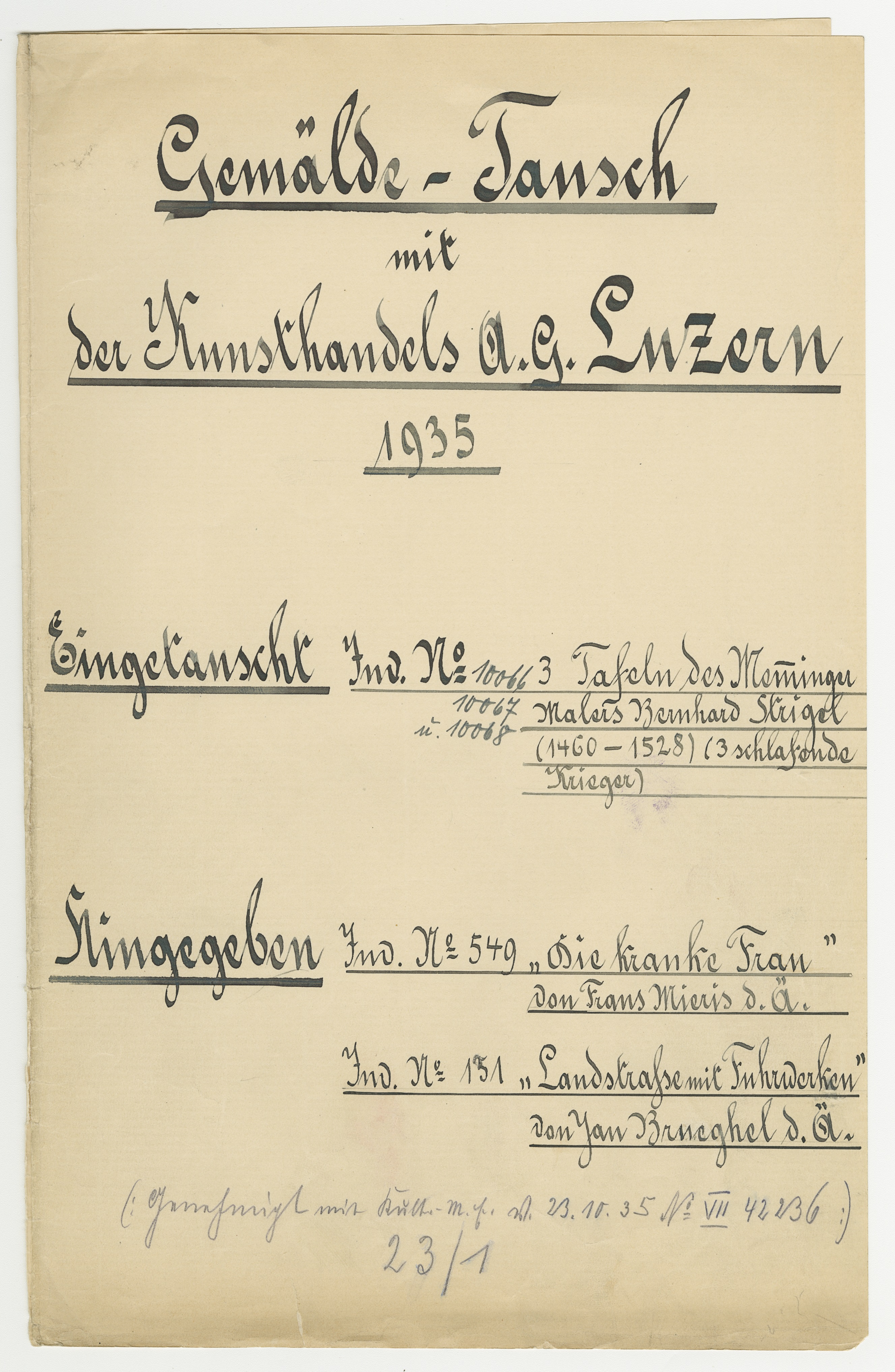

In 1935, the Bavarian State Painting Collections (Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen), under the management of director Ernst Buchner (1892-1962), sold an outstanding painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) depicting a Forest Road with Travellers (fig. 1).1 This was, however, not a straightforward sale but rather a complex exchange transaction which, among others, involved the Munich art dealer firm Julius Böhler. Apart from the Brueghel painting, a picture by Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635-1681) entitled The Doctor’s Visit2 (fig. 2) also left the collection in the process to acquire three panels (fig. 5) by the Early German painter Bernhard Strigel (ca. 1460/61-1528) in return.3

Fig. 1: Jan Brueghel the Elder: Forest Road with Travellers, 1610, oil on panel, 37 × 58 cm, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Inv.Nr. 2020.26.1

What was the role of the firm of Julius Böhler in this transaction? The company had been founded in 1880 in Munich and, by the turn of the century at the latest, had become one of the largest and most important art dealerships in Germany. Its founder Julius Böhler (1860-1934), who originated from the Black Forest, gained an excellent reputation among collectors and museums in a short period of time and rose to become a highly successful art dealer. His royal warrants as “Königlich-preußischer Hofantiquar” in 1895 and as “Königlich-bayerischer Hofantiquar” in 1906 demonstrate that he was highly regarded. Soon, the Böhler firm had a well-functioning network in Europe and the US at its disposal and operated at an international level, with particularly sought-after market expertise for museum quality artworks. In 1906 and 1910 Böhler’s sons Julius Wilhelm (1883-1966) and Otto Alfons (1887-1950) successively became partners in the business.

Julius Wilhelm decided in 1920 to found a sister company based in Lucerne together with the dealer Fritz Steinmeyer (1880-1959) from Cologne, trading under the name “Kunsthandels AG Luzern” (KHAG). Otto Alfons instead remained in Munich, working from 1922 with the art historian Dr. Hans Sauermann (1885-1960). The Munich management was also joined in 1928 by the founder’s grandson Julius Harry Böhler (1907-1979), son of Julius Wilhelm. Even though he was drafted into the air force in World War II, he nevertheless was surprisingly active as a dealer in this period.4

Among the clients of the firm were numerous museums, including the Bavarian State Painting Collections. No doubt the company directors were fully aware of the museum’s acquisition interests, since they were in close contact with its director general since 1933, Ernst Buchner. Out of almost 30,000 index cards created by the dealer firm which are currently recorded in a database, around sixty refer to the Alte Pinakothek, part of the state museum collections.5 Around half of these cards record the museum as a previous owner of an artwork, the other half as subsequent owner.6 It becomes apparent on analysing the card index that the Pinakothek had sold artworks to the firm of Böhler as early as in the 1920s. For example, a Brueghel landscape with figures had been deaccessioned in 1923 and then resold by Böhler to the KHAG Lucerne,7 and a series of paintings with triumphal subjects by the school of Mantegna had been deaccessioned in 1924. The latter had originally been in the collection at the Castello Marchese Colloredo in Udine and had been bought by Böhler in Florence in 1905.8 The Pinakothek placed the pictures on commission with the KHAG Lucerne which in turn sold them to several other dealers. In 1927, the entire series was bought by the Kress Collection. It is now attributed to Girolamo da Cremona (1451-1483) and on display in the Denver Art Museum.9

Fig.2: Frans van Mieris the Elder, The Doctor’s Visit, 1667, oil on panel, 44,5 × 31,1 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv.no. 86.PB.634.

It seems likely that the banker and art collector Franz Koenigs (1881-1941) was involved as an intermediary to sell the pictures in different ownership as a single group to the Kress Foundation. His name appears on the index cards as business partner.10 As a final example, Buchner’s predecessor Friedrich Dörnhöffer (1865-1934) sold a further three paintings to Böhler, including two by Paolo Veronese (1528-1588).11

Under director general Ernst Buchner, the practice of deaccessioning continued, as did the business relationship that his predecessor Dörnhöffer had maintained with the art trade, including Böhler.12 Buchner did not need to establish entirely new connections, as he had already been in close contact with Böhler during his time as director of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum in Cologne from 1928 and 1932.13 As Theresa Sepp states in her dissertation on this period: “Buchner paid regular visits to Böhler at Briennerstrasse 12 and kept abreast by telephone or in person about the stock in trade. Böhler (...) informed him when he had spotted interesting paintings; in return he relied on Buchner’s expertise in identifying artist names, attributions, or questions of authenticity.”14

The working relationship is clearly visible in the card index of the Böhler firm. Eighty-seven of the cards recorded to date list Buchner as expert.15 The reason was an increasing demand for expert certificates for high value art objects, which could be nearly impossible to sell without. Wealthy clients such as Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza would even insist on up to four expert certificates for their purchases. As art market prices rose, clients tried to avoid forgeries by obtaining expertise on artworks’ quality and authorship – and thus, authenticity. The value of expert certificates increased in line with the reputation of the authoring expert, so that museum directors like Ernst Buchner were particularly in demand.16 An undated annotation by Fritz Steinmeyer, Böhler’s business partner, gives a vivid impression of the system of favours and dependencies, in this case with reference to Wilhelm von Bode: “At the request of dealers and collectors, he [Wilhelm von Bode] would put down in writing his view of the master and other relevant facts on the object in question – without charge. As an excellent connoisseur, he was soon inundated with enquiries; collectors wished to have his certificates, and dealers were more or less forced to make use of his services. In this way he was always informed about supplies in the art market, and about the objects sought by individual collectors. If anything appeared in the trade that was desirable for his own museum, he requested it as a gift for the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, in return for expertise delivered and for acting as an intermediary for sales to collectors who only bought on his advice. In this way, important private collections were formed, and the museum received many magnificent artworks free of charge.”17

Buchner also received important donations from dealers, including Böhler.18 The latter in turn benefited from proximity to Buchner, for example by storing part of his stock in trade in the wartime storage depot of the Bavarian State Painting Collections, thus protecting it from air raids.19 Transactions by exchanges were also part of their professional relationship, as will be shown in the following.

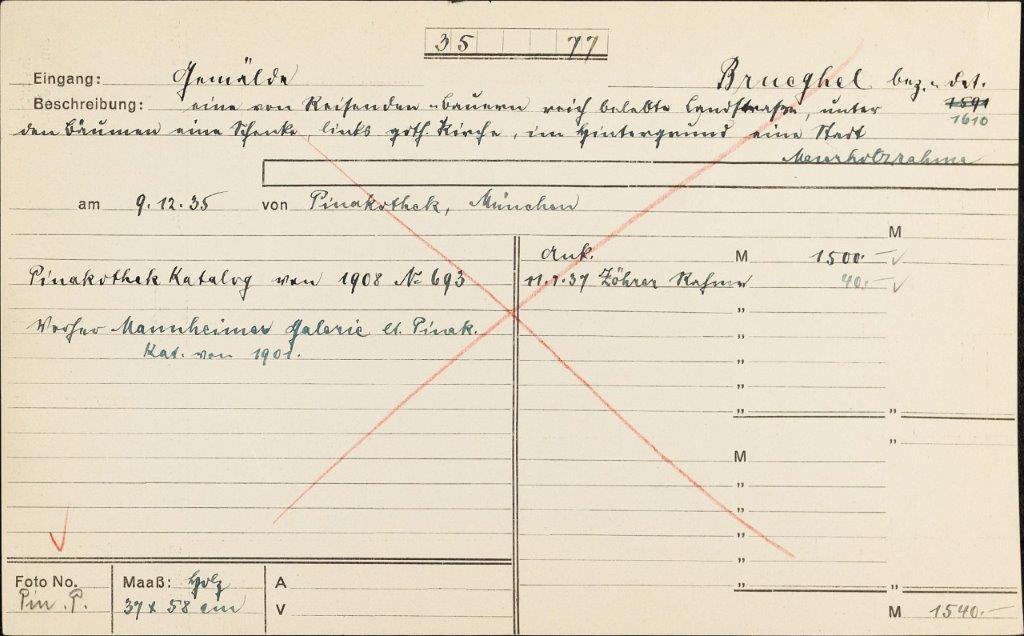

Fig.3: Index card for the painting Forest Road with Travellers by Jan Brueghel the Elder (today National Gallery of Art, Washington), Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, München / Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, Karteisystem München, M_35-0077.

Conversely, the exchange transaction in question is not visible on the Böhler card index, even though employees of the firm frequently noted this type of transaction on the cards. The card for the Brueghel painting records the following (fig. 3): on 9 December 1935 Böhler acquired a painting by Jan Brueghel the Elder from the Alte Pinakothek, dated 1610, painted on panel, measuring 37 x 58 cm, for the price of 1,500 marks. The registration included a descriptive title, as usual: “a country road populated by numerous travellers and farmers, under / the trees a tavern, a gothic church on the left, a town in the background”. Two catalogues are listed and provide references on provenance: “Pinakothek catalogue of 1908 no. 693 / previously Mannheimer Galerie acc. to Pinak. cat. of 1901”. The back of the index card reveals that the picture was not with Böhler for long, as he would sell it to the Düsseldorf gallery Stern for 7,500 marks as early as 11 January 1936, after the restorer Wilhelm Panzerbieter, frequently consulted by Böhler, had it in his workshop.20 Böhler received a photograph by Bruckmann from the Pinakothek, annotated as “Pin. P.”, which was needed for the photo file.

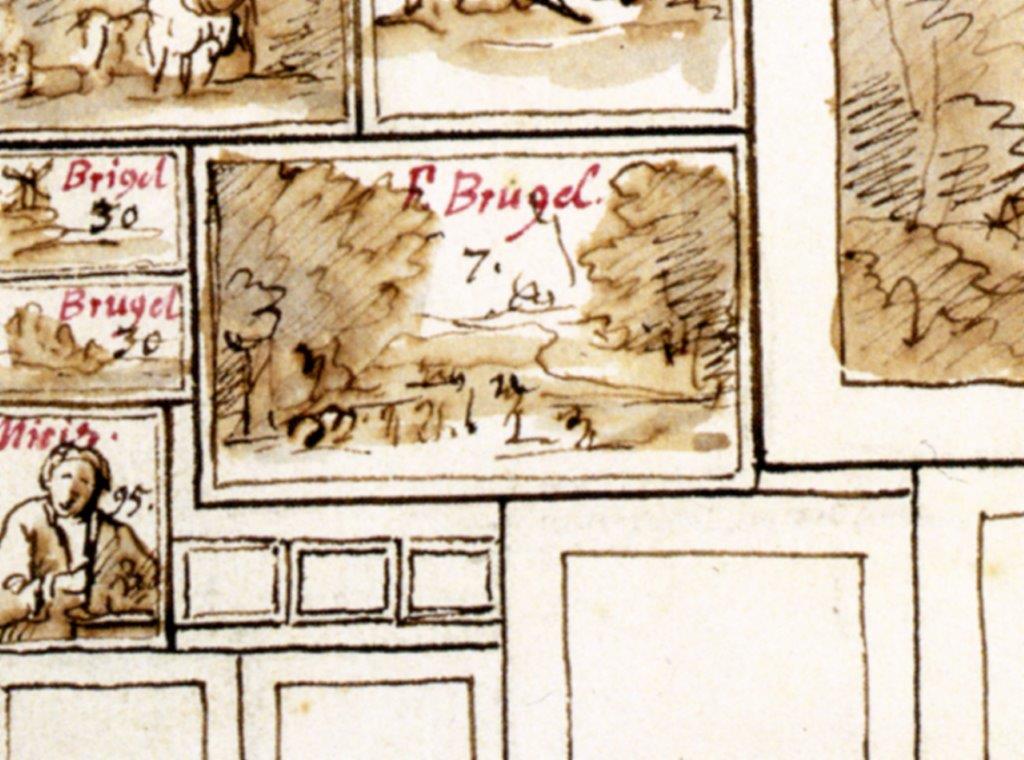

It was only in 2020 when the Washington National Gallery of Art wanted to buy the painting and asked about its provenance in detail – especially during the National Socialist era – that more profound research began. This investigation not only demonstrated the exchange transaction, but in fact established a continuous chain of ownership for the painting from the eighteenth century to the present: it was first in the Düsseldorf gallery of the Wittelsbach Elector Johann Wilhelm von der Pfalz (1658-1716), where it was listed in the catalogue in 1719/1720 as no. 7.21 The picture then went to Mannheim when Karl Philipp von der Pfalz (1661-1742) moved his residence there. In the corresponding catalogue from 1731 it is noted with a small drawing (fig. 4).22 Due to the Bavarian line of succession through the Palatinate line of the Wittelsbach dynasty and the transfer of the Mannheim collection to the Munich Pinakothek, the picture came to the Bavarian capital. Since 1822 it was listed in the Royal Bavarian Central Painting Collections under no. 396,23 at the latest from 1838 in the Royal Pinakothek in Munich.24 Almost a century later, Buchner sold it in December 1935 – as stated above – to the art dealer Böhler who resold it to Galerie Stern in Düsseldorf. Böhler had a friendly exchange with Max Stern and expressed his expectation of reciprocal “nice” offers from his Düsseldorf colleague, once the transaction had been completed.” I am delighted that we came to an agreement after the tough battle, and hope that you can now also offer something really nice to us as well.”25 Stern in turn sold the Brueghel before September 1938 to the family of Richard Friede (1883-1944) in Bocholt who emigrated to the US in 1941.26 The picture passed through inheritance to Friede’s daughter Ursula Bamberger (1922-2019), then to the dealer Otto Naumann Ltd in New York in 1992, jointly owned with his colleague Roman Herzig of Galerie Sanct Lucas in Vienna, and in the same year to Bernheimer Fine Old Masters in Munich. In 1995, Bernheimer sold it to the private collector Marietta Vok (ca. 1941-2019) in Austria. From there it was donated in January 2018 to a private collection in Italy, and from March 2020 it was with Galerie David Koetser in Zurich, who eventually sold it to the National Gallery of Art in Washington in November 2020.27 Yet this uninterrupted chain of provenance which is published on the museum’s website still does not reveal anything about the complex exchange between the Alte Pinakothek and the firm of Böhler, which only becomes apparent when consulting the files in the Bavarian State Painting Collections.

Fig.4: Johann Philipp von der Schlichten: The art gallery of the Elector Karl III. Philipp von der Pfalz in the royal residence in Mannheim, 1731. First room of paintings, wall IIa. (detail), Paris, Bibliothèque de l’INHA, Collections Jacques Doucet

The archives of the Bavarian State Painting Collections preserve an instructive letter from the Swiss art dealer Theodor Fischer (1878-1957) in Lucerne to Ernst Buchner, dated 30 April 1935. It refers to three paintings by “Striegel” (sic) which Fischer had purchased from the Viennese Count Wilhelm von Erdödy28 and sent to Munich through Julius Wilhelm Böhler in order to show them to Buchner and offer a potential acquisition. As the managing director of the KHAG, Julius Wilhelm Böhler was the nearest neighbour of Fischer in the Haldenstrasse in Lucerne. They cooperated on business matters in many cases. In the letter, Fischer reminded Buchner of the latter’s desire to buy the panels owned by Fischer for the Pinakothek, and referred somewhat vaguely to the terms: “and Herr Böhler arranged an exchange with you on my behalf”. As several months had gone by, he now wanted to know Buchner’s decision.29 Within a day, Buchner promptly responded to indicate clearly that he was still interested in the transaction: “I hope that the acquisition of the pictures through an exchange with disposable pictures from the state collections can be brought to a close over the next few weeks.”30 Three months later, he formally applied for the exchange at the responsible ministry for education. But the partner for the exchange was now named as KHAG Lucerne, that is the sister-firm of Böhler, and no longer Theodor Fischer in Lucerne, who had after all declared himself to be the owner in the abovementioned letter of 30 April 1935. The three “highly important, unusually attractive, and unique panels by the Memmingen painter Bernhard Strigel” – depicting sleeping tomb guards from a Christ’s resurrection ensemble – were “most desirable” for the collection of the Alte Pinakothek (fig. 5). The price of 8,000 marks each could be described as reasonable in view of the quality and rarity. Since Buchner already knew that these funds were not available, he suggested the following: “Since there are no liquid funds available, I suggest to purchase the pictures by way of an exchange with disposable pictures from state property.” The Netherlandish school was “abundantly represented” in his collection, which is why he proposed to deaccession the abovementioned paintings by Mieris and Brueghel. He set the value for the Mieris at 20,000 marks and the Brueghel at 4,000. He made the exchange palatable with a patriotic phrase: “Through this exchange the recovery of valuable and important German artworks from abroad will be enabled, without incurring noticeable losses of artistic value at the State Painting Collections.”31

Fig. 5: Bernhard Strigel, Sleeping Tomb Guard with Mace and Sword, 48,6 x 46 cm, inv. no. 10066; Sleeping Tomb Guard with Sword and Halberd, 48,3 x 45,5 cm, inv. no.. 10067; Sleeping Tomb Guard with Crossbow, 48,2 x 45,8 cm, inv. no.. 10068, all: circa 1520/21, oak panel, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, München

Once the agreement was received on 23 October from the ministry, which seems to have found the argument convincing that “the three Early German panels would represent a considerable artistic gain for the Bavarian State Painting Collections, and the deaccession of the two Netherlandish works no discernible loss”,32 Buchner still needed to liaise with the foreign currency office in the finance department for Bavaria. Once again, he had to come up with convincing arguments, which Buchner formulated as follows: “The exchange does not require any foreign exchange funds, it is intended to recover unique and precious cultural assets from abroad, whereas the two Netherlandish pictures due to be passed to the Kunsthandels-AG in Lucerne are unquestionably of lesser importance and disposable when taking into consideration the care for German art.”33 On 6 December, Böhler finally delivered the “approval of the Swiss clearing office” for the exchange and requested a swift handover of the two Netherlandish pictures.34 A confirmation of the exchange can be found in an annotation in the inventory of the Bavarian State Painting Collections, probably dating from the end of 1935 (fig. 6).35

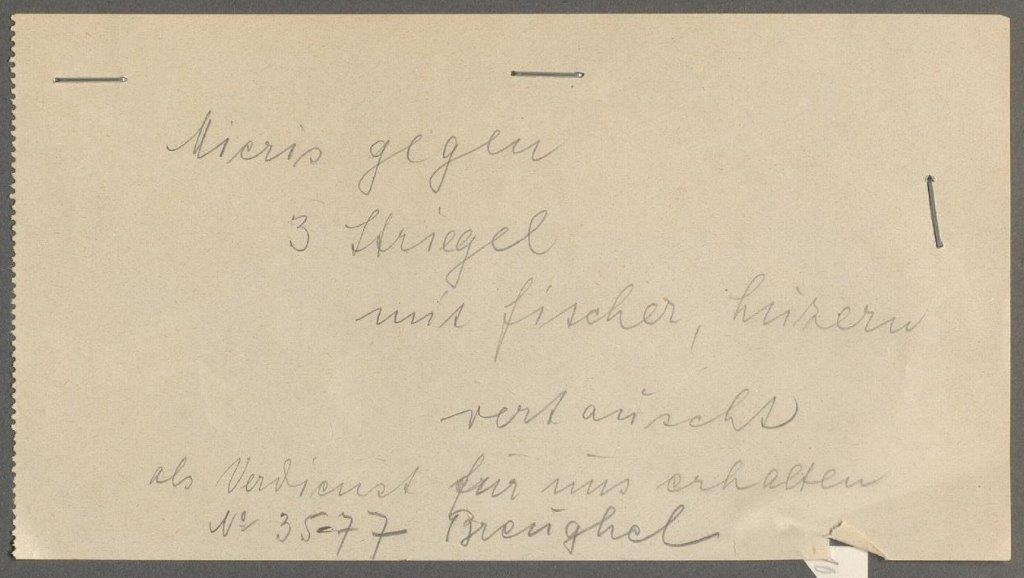

While the intake of the painting by Mieris is recorded on an index card in Lucerne, the Brueghel painting received an index card in Munich, though not with the value of 4,000 marks stated by Buchner but rather with a much lower purchase price of 1,500 marks. Why were the two paintings differently accounted for? An explanation can be found in a small note attached to the back of the photo file for the Mieris painting: “Mieris exchanged for 3 Striegel with Fischer, Lucerne / received as profit for us no. 35-77 Breughel” (fig. 7).36 The Brueghel painting was therefore the KHAG Lucerne’s remuneration for an introduction to the Pinakothek, and the sum of 1,500 marks was probably to be read as symbolic. A transaction between a German museum and the sister-company of a Munich dealer was likely to meet with the authorities’ approval more easily than a direct transaction with a Swiss dealer like Theodor Fischer.37

Fig. 6: Exchange of paintings with Kunsthandels AG Luzern 1935, in: Inventar der Alten Pinakothek, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0009

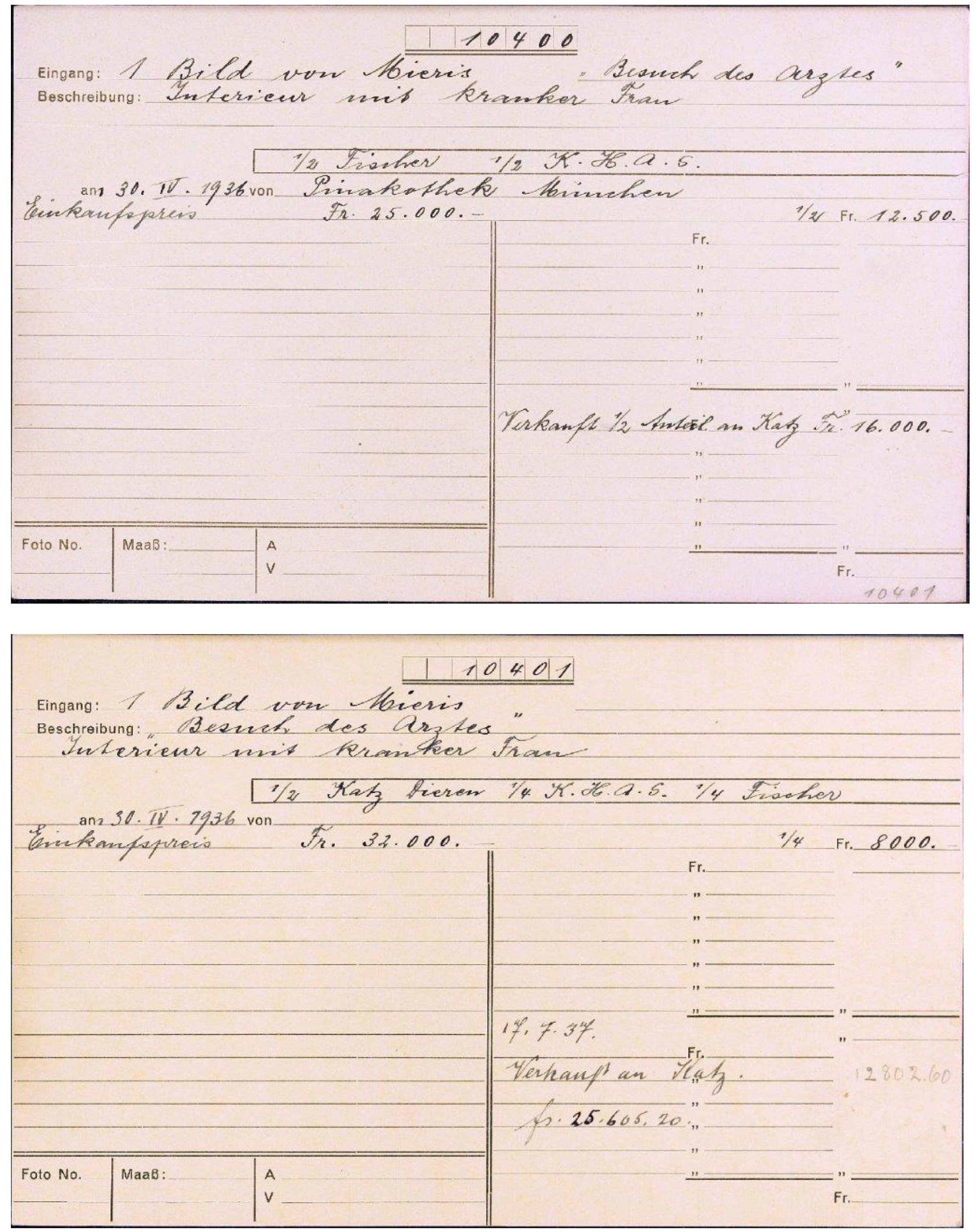

For the painting by Mieris, two consecutive cards are held in the Lucerne index (fig. 8). Card no. 10400 records the receipt of the picture entitled The Doctor’s Visit/Interior with a Sick Woman. The previous owner is recorded as Alte Pinakothek in Munich, it is however peculiar that the receipt was dated five months later, on 30 April 1936. At that point, Theodor Fischer’s firm is noted as having a 50 percent share in the sum of 25,000 Swiss francs. But KHAG and Fischer promptly sold half of the picture to their Dutch colleague Katz for 16,000 Francs, making a profit of 3,500 francs in the process. The second index card for the picture in Lucerne, no. 10401, bears the same date but oddly enough notes a different purchase price at 32,000 francs. Three partners were now trying to sell the picture jointly: Katz with a fifty percent share, and KHAG and Fischer with twenty-five percent each. Initially Katz took the picture in on commission and ultimately bought the remaining share on 17 July 1937 for 25,605.20 francs, perhaps because he had found a client for it. Consequently, KHAG and Theodor Fischer did not make a significant profit from the sale of the picture. The firm of Katz, one of the largest art dealers in the Netherlands, was based in Amsterdam and specialized in Dutch and Flemish art of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Mieris painting fit their profile precisely.38

Fig. 7: Verso of the photo file on the painting The Doctor’s Visit by Frans van Mieris the Elder (today The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, München / Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, Fotomappe, L_10400

On 19 June 1986, the picture was bought by the J.Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles at a Sotheby’s sale in Monaco. Like the Brueghel painting, it has a long and illustrious provenance which is published on the museum’s website: formerly in the collection of the Wittelsbach family members Johann Wilhelm and Karl Philipp von der Pfalz, it therefore also came to Munich via the collections in Düsseldorf and Mannheim and finally joined the Bavarian State Painting Collections. Yet for the year 1935, the information on the museum website differs from Böhler’s archival sources, which still needs to be resolved. The museum states: “sold to A.G. Zurich, 1935” and then “1935-1937: A.G. Zurich (Eindhoven, The Netherlands)”. For the year 1937, the provenance information tallies again: “1935-1937: Kunsthandel Firma D. Katz (Dieren, The Netherlands; Basel, Switzerland; The Hague, The Netherlands)”. Prior to acquisition by the Getty Museum, the picture had been in Den Haag, Almelo, Scheveningen, Stockholm, Paris, and Monaco.39

Both Netherlandish paintings are publicly accessible today, hanging in the rooms of highly prestigious US museums in Washington and Los Angeles. Without doubt, they meet their high-quality standards. Instead, the three tomb guards by Strigel are no longer exhibited. While the museum website still notes that these “impressive paintings” are on view in the Alte Pinakothek, they were removed in the course of the closure of the Neue Pinakothek in order to make way for masterpieces from the nineteenth century.40 Incidentally, Strigel had painted a series of tomb guards for a Holy Grave and the curators of the Pinakothek think that it is likely that the panels were taken from a Holy Grave at the parish church Unserer Lieben Frauen in Memmingen that is documented for the period around 1521/22.41

Fig. 8: Index cards for the painting The Doctor’s Visit by Frans van Mieris the Elder (today The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles), Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, München / Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, Karteisystem Luzern, L_10400 und L_10401

It is striking that Buchner reached for the stock of Netherlandish paintings on a regular basis in his exchange transactions, as Andrea Bambi noted: “In exchanges, he deaccessioned, among others, ten works by Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568–1625), seven by Gerard Dou (1613–1675), five by Frans van Mieris the Elder (1635–1681), three by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) and two each by Isaak (1621–1649) and Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685) and Cornelis Jansz de Heem (1631–1695).” In terms of quantity, she argues: “Buchner could permit himself to deaccession ten works by Jan Brueghel, as the State Painting Collections at the time disposed of more than seventy works by the artist. Nevertheless, he noticeably reduced the holdings for Dou by giving away almost forty percent.”42 From a contemporary perspective, Netherlandish painting may have been considered less valuable than Early German painting and deaccession justifiable due to the large amount of works in the collection.43 Yet in terms of quality and also with view to collection history, the loss of this top-quality painting by Brueghel now owned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, was – and is – painful for the museum in Munich, even though it was only one among seventy.

Modern paintings also left the collection to be exchanged for art that conformed to the taste of the day. Bambi notes that Buchner deaccessioned fifty-two modern works, including the important paintings La Pointe de La Hève from 1864 by Claude Monet (1840-1926) and La Place Saint-Marc from 1881 by Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), which had been acquired for the Neue Pinakothek in 1907 and 1911/12 (fig.9). The firm of Böhler was also involved in these exchanges, even though French Modernism was nowhere near its core business. Excellent business relations clearly won the day.

Fig. 9: Pierre-Auguste Renoir, La Place Saint Marc, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Notably, this exchange took place at a time when the works had already been moved to a depot in Neuschwanstein castle to protect them from bombing. On 23 January 1940, they were taken back to the Alte Pinakothek and handed over to Böhler and his fellow dealer Karl Haberstock (1878-1956) from Berlin in February 1940. By ministerial decision of 9 April 1940 they were exchanged for an at the time vastly overpriced, though rare painting by Hans Thoma (1839-1924) entitled Girl Feeding Chickens (http://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/6kLa6Q9G8V). The two French paintings were still in Böhler’s stock after the end of the war, and a hot debate ensued in the post-war period about the legality of the exchange, in the hope of recovering the works.44 To no avail, as Böhler was able to sell them in 1950, and today they are in the National Gallery in London45 and in the Minneapolis Institute of Art (fig. 10)46. While they are on view in both museums, the picture by Thoma is currently stored in the depot, as are the panels by Strigel.47

The card index in the archive of the Central Institute for Art History demonstrates that Böhler in Munich, respectively the KHAG Lucerne acquired many more paintings from the Pinakothek. There is a picture by Caspar Netscher, Lady with a Parakeet, bought in 1936 and sold to Katz in 1937,48 a River Bank with Ferry by Salomon van Ruysdael, also bought in 1936 and sold to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia in 1937,49 an Adoration of the Magi by Adriaen Isenbrant, bought in 1936 and sold to Richard Zinser in Stuttgart in 1936,50 a Village Scene by Brueghel, bought in 1937 and sold to the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn in 1937,51 a Netherlandish Virgin with Child, bought in 1937 and sold in the same year to O. G. Begg & Co. London,52 a Still Life in the manner of Rachel Ruysch, bought in 1937 and sold to an unnamed cash buyer in 1938,53 a Still Life by Jan Davidszoon de Heem, bought in 1939 notified to the government in 1947 and sold in the following year,54 a Landscape with a Castle and Hare Hunt by Jan Wynants (circa 1632-1684), bought in 1939 and sold in the same year to the Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn,55 as well as the pictures that were included in the exchange for the painting by Hans Thoma in 1940: in addition to the above-mentioned Monet and Renoir, there were a Flower Still Life by Herman van der Mijn (1684-1741),56 a work by Adolph von Menzel (1815-1905) entitled Wearers of Armour and Commanders,57 a painting Diana with the Hunter’s Catch by Peter Paul Rubens, Frans Snyders (1579-1657), Hendrik von Balen (1575-1632) and Jan Brueghel II58 and also a Landscape with a Hunter and Dog by Jan Wynants.59

Today, there is a general agreement in Germany that artworks in a public German museum collection should remain in place. Deaccession is not envisaged, since the transparency of the collection history is considered as important as the preservation of the objects in the collection – even though acquisitions may in hindsight appear as mistakes. Yet for decades, even centuries, deaccessions or “improvements” of a collection were standard practice. Like many other museums, the Bavarian State Painting Collections deaccessioned large parts of its collection in order to use the proceeds for shifts in its emphasis. Especially during the National Socialist era, many museum directors sought to reform the profile of their institutions, be it through pressure applied from outside or by choosing to “adjust to current taste”. The regime expected German art, and museums ensured that the directive was put into practice – some with greater enthusiasm than others. Ernst Buchner, a specialist for Early German painting, focused his acquisition funds on Old Masters, spending ninety-three percent of his budget on them.60

Consequently, Buchner did not hesitate even to reduce his high-quality collection of non-German art in order to acquire German art instead, a process that – as shown above – led to painful losses for both Alte and Neue Pinakothek and gains for museums elsewhere, in this case in Washington and Los Angeles. He deaccessioned masterpieces and acquired works in the collection that currently languish in the depots of the Bavarian State Painting Collections. “Not worthy of the Pinakothek” – such was the title of an article by the provenance researcher Andrea Bambi from 2016, where she traced Buchner’s exchanges and exhibitions from 1933 to 1945. The reader will find that during his time as director general, Buchner acquired almost nine hundred artworks and deaccessioned – often by way of exchange – a staggering seventy-three works of Netherlandish painting, nine works from the Italian School and two French pictures. It is important to bear in mind that after 1933, exchanges provided the only viable method for Buchner, since no foreign currency was available for acquisitions by the Bavarian State Painting Collections in the art trade abroad. Through exchanges, a need for direct monetary transfer could be circumvented.61 Foreign exchange regulations were strict not only with regard to export but also payment. In order to receive the required funds for purchases in foreign currency, it was necessary to declare in advance, which works would be acquired at which price, and apply for the requisite sum. Only with the necessary authorization could the funds be released. Spontaneous purchases were thus impossible.62 In this context, the exchange of the two paintings by Brueghel and Mieris in return for the three panels by Strigel is only one example among many.

Birgit Jooss was head of the project to process and analyze the archive of the art gallery of Julius Böhler at the Central Institute for Art History in Munich in 2020-2022. Today, she heads the Arts and Culture Department of the Wittelsbacher Ausgleichsfonds in Munich.

Translation: Susanne Meyer-Abich

1 This article is based on provenance research by Christian Fuhrmeister, Stephan Klingen, Willi Korte, and Anne Uhrlandt, conducted in the context of acquisition procedures at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in 2020. I am grateful for the material provided. Great thanks also to Stephan Klingen and Christian Fuhrmeister for a critical reading of this article. – On the painting in question: Jan Brueghel the Elder, Forest road with travellers, 1610, oil on panel, 37 × 58 cm, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, National Gallery of Art, Washington, inv.no. 2020.26.1: https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.222552.html#provenance. See also in the catalogue raisonné: https://www.janbrueghel.net/object/woodland-road-near-a-village. Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte (ZI) München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_35-0077.

2 Frans van Mieris the Elder, The Doctor’s Visit, 1667, oil on panel, 44,5 × 31,1 cm, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, inv.no. 86.PB.634: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/800/frans-van-mieris-the-elder-the-doctor’s-visit-dutch-1667/.

3 Bernhard Strigel, Sleeping tomb guard with a mace and sword, circa 1520/21, oak panel, 48,6 x 46 cm, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (BStGS), inv. no. 10066, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/gR4kZOQGEe. – Sleeping tomb guard with a mace and halberd, circa 1520/21, oak panel, 48,3 x 45,5 cm, BStGS, inv. no. 10067, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/ZnxwNPE4Xg. – Sleeping tomb guard with a crossbow, circa 1520/21, oak panel, 48,2 x 45,8 cm, BStGS, inv. no. 10068, https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/ZKGPQbM4gA.

4 On the art dealer firm of Julius Böhler, see Richard Winkler, “Händler, die ja nur ihrem Beruf nachgingen”. Die Münchner Kunsthandlung Julius Böhler und die Auflösung jüdischer Kunstsammlungen im “Dritten Reich”, in Andrea Baresel-Brand (ed.), Entehrt. Ausgeplündert. Arisiert. Entrechtung und Enteignung der Juden (Magdeburg: Koordinierungsstelle für Kulturgutverluste, 2005), 206–246; Meike Hopp, Kunsthandel im Nationalsozialismus. Adolf Weinmüller in München und Wien (Köln: Böhlau, 2012), 112–121; Timo Saalmann, Langjährige Kontakte. Die Münchener Kunsthandlung Julius Böhler, in Anne-Cathrin Schreck/Anja Ebert/Timo Saalmann (eds.), Gekauft – Getauscht – Geraubt? Erwerbungen des Germanischen Nationalmuseums zwischen 1933 und 1945 (Nürnberg: Germanisches Nationalmuseum 2017), 24–37; Anja Ebert, “... so wär’s schon sehr nett wenn Sie recht bald wieder kommen könnten”. Die Geschäftsbeziehungen von Henri Heilbronner und Julius Böhler in der NS-Zeit, in Ebert/Saalmann/Schreck, Gekauft – Getauscht – Geraubt?, 38–43; Sophie Katharina Oeckl, Die Zusammenarbeit der Kunsthandlungen Julius Böhler München und Karl Haberstock Berlin. Eine Analyse gemeinsam gehandelter Gemälde zwischen 1936 und 1945 (München: LMU München, 2015), https://doi.org/10.5282/ubm/epub.29488; Birgit Jooss, articles in the ZI blog: https://www.zispotlight.de/tag/julius-boehler/; Birgit Jooss, La Kunsthandlung Böhler Munich, in Répertoire des acteurs du marché de l’art en France sous l’Occupation, 1940–1945 (RAMA), in German and French, https://agorha.inha.fr/database/76 [released 3 December 2021].

5 As of 28 December 2021.

6 Conceived as a project, the card index preserved since 2015 at the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in Munich is digitalized and analyzed in-depth. It consists of circa 30,000 object index cards, 8,000 photo files, and 4,000 client cards dating from 1903 to 1993. Each traded object received an index card, filed under Munich, Lucerne, or Commissions. Since 2017 the card index is analyzed with funding by the Ernst von Siemens Foundation for the Arts, and since 2019 the cataloguing of the results in a database is funded by the German Lost Art Foundation.

7 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_23-0281.

8 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index Luzern, L_04000 bis L_04007.

9 Today in the Kress Foundation, New York: https://www.kressfoundation.org/kress-collection/artist/attributed-to-girolamo-da-cremona.

10 Franz Koenigs was a partner in the two banks “Delbrück, Schickler & Co., Berlin” and “Delbrück, von der Heydt & Co., Köln”. He also founded the bank “Bank Rhodius Koenigs Handel Maatschappij” with its head office in Amsterdam. See: http://www.koenigs.nl/franz/.

11 Paolo Veronese, Flight into Egypt, ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_27-0072; Paolo Veronese, Lady with a boy, ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_27-0073 and Ottmar Elliger: Feast, ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_27-0096.

12 Andrea Bambi, “Nicht pinakothekswürdig”. Ernst Buchners Museumspolitik und ihre Folgen. Tauschgeschäfte und Ausstellungen in den Pinakotheken 1933-1945, in Jahresbericht Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen 2016, 26-135, here 128.

13 Theresa Sepp, Ernst Buchner (1892–1962). Meister der Adaption von Kunst und Politik (München: LMU München, 2020), https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/26875/, on Buchner as museum professional, 76-94, especially 93 and 112.

14 Sepp, Ernst Buchner, 113.

15 As of 28 December 2021. Additions are to be expected as the index cards continue to be analysed.

16 The well-developed system of expertise provision eventually gave rise to the so-called expertise quarrel in 1930. Johannes Gramlich, “Jedem der Experten einen Judenhut aufstülpen”. Der ‘Expertisenkrieg’ und die ,Sammlung Schloss Rohoncz’ in der Neuen Pinakothek 1930, in Jahresbericht Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen 2017, 182-192; conference report: Expertise. Das Kunsturteil zwischen Geschichte, Technologie, Recht und Markt, 16 May 2013 – 17 May 2013, Zurich, in H-Soz-Kult, 7 October 2013, www.hsozkult.de/conferencereport/id/tagungsberichte-4983.

17 Typoscript by Fritz Steinmeyer, undated, family archive Steinmeyer Zurich, digital copy in the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Munich.

18 Sepp, Ernst Buchner, 87, note 182.

19 See the letters: Böhler to Offiziant Federl, Schloss Dietramszell, 21 October 1943. – Böhler to Buchner, 13 August and 21 October 1943. – Buchner to Böhler, 17 August 1943 Bayerisches Wirtschaftsarchiv, F 43/351. – Sepp, Ernst Buchner, 113.

20 Böhler typically wrote a brief note “Panzerbieter“ on the index cards. This refers most likely to the Munich painter, copyist, and printmaker Wilhelm Panzerbieter (1869-1954), who also worked as a restorer. See Volker Duvigneau and Gude Suckale-Redlefsen (eds.), Plakate in München 1840 – 1940. Eine Dokumentation zu Geschichte und Wesen des Plakats in München aus den Beständen der Plakatsammlung des Münchner Stadtmuseums (München: Lipp, 1975).

21 Detail Des Peintures du Cabinet Electoral du Dusseldorff / Gemäldegalerie Düsseldorf. - [online edition.]. - [S.l.], [ca. 1720?], http://diglib.hab.de/drucke/uc-kapsel-1-12s/start.html.

22 Johann Philipp von der Schlichten, Gemäldekabinett des Kurfürsten Karl III. Philipp von der Pfalz im Residenzschloss Mannheim, 1731. Erstes Gemäldekabinett, Wand IIa., Paris, Bibliothèque de l’INHA, Collections Jacques Doucet, vgl. Reinhold Baumstark (ed.), Kurfürst Johann Wilhelms Bilder – Sammler und Mäzen, Bd. 1, (München: Hirmer, 2009), 252.

23 Johann Georg von Dillis, Inventarium der Königl. Baier. Central-Gemälde-Sammlung, 11 vols. Archiv der Bayerischen Staatsgemäldesammlungen, see Baumstark, Kurfürst Johann Wilhelms Bilder, 185.

24 Georg Dillis, Verzeichniss der Gemälde in der Königlichen Pinakothek (München: Königliche Pinakothek, 1838), 205, no. 198. – Rudolf Margraff, Die ältere königliche Pinakothek München (München: Königliche Pinakothek, 1872), no. 790 (198). – Katalog der Gemälde-Sammlung der Kgl. Älteren Pinakothek in München, mit einer hist. Einl. von Franz von Reber (München: Verlagsanstalt für Kunst und Wissenschaft, 1888), 142, no. 693 (formerly 790). – Katalog der Gemälde-Sammlung der Kgl. Älteren Pinakothek in München, Ausgabe mit zweihundert Abbildungen, mit einer hist. Einl. von Franz von Reber (München: Bruckmann, 1908), 150, no. 693.

25 Kunsthandlung Böhler [author unidentified] to Max Stern, Munich, 10 January 1936, BWA F43 / 85, Galerie Stern, Düsseldorf.

26 Declaration of assets by Richard Friede dated 8 September 1938 for the Reich foreign exchange office [Reichsdevisenstelle]. Page b, pag., 17. Landesarchiv NRW, Abteilung Westfalen, L 001a, Oberfinanzdirektion Münster, Devisenstelle, no. 2185, regarding: Heirs of Friede Bocholt.

27 Brueghel had painted the subject in three variations: Claus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, Jan Brueghel der Ältere (1568-1625). Kritischer Katalog der Gemälde. vol.1 Landschaften mit profanen Themen (Lingen: Luca, 2008), 158, cat. 53 and the following. The sale to Washington proceeded in agreement with the Max and Iris Stern Foundation, Montreal.

28 See the letter by Dr Wilhelm Graf von Erdödy, Schottengasse 7, Vienna to the director’s office of the Alte Pinakothek dated 17 April 1939. BStGS_Bildakt10004_Erdödy_Buchner_1939_04_14. I am grateful to Anja Zechel for the helpful information she provided on 31 January 2022.

29 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Buchner, Lucerne, 30 April 1935, Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv, München (BayHstA), Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0017.

30 Ernst Buchner to Theodor Fischer, Munich, 1 June 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0016.

31 Ernst Buchner to the Staatsministerium für Unterricht und Kultus, Munich, 29 August 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0012 and 0013.

32 Ernst Buchner to the Landesfinanzamt, Devisenstelle, Munich, 31 October 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0014 and 0015.

33 Ernst Buchner to the Landesfinanzamt, Devisenstelle, Munich, 31 October 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0014 und 0015.

34 Julius [Harry or Wilhelm] Böhler to Ernst Buchner, Munich, 6 December 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0010. See also the approval dated 3 December 1935: Exchanged Mieris against 3 pictures by Strigel valued at 30,000 Swiss francs each, letter of 12 December 1935, BStGS_Bildakt10066_Fischer. Information kindly provided by Anja Zechel on 31 January 2022.

35 Exchange of paintings with Kunsthandels-AG Luzern 1935, BayHstA, Staatsgemaeldesammlungen_vorl_Nr.Reg.AZ-231_1_0009.

36 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, photo file, L_10400 and L_10401.

37 It is impossible to confirm whether Fischer had the object in stock already and also whether a commission was paid to KHAG for the introduction.

38 On the art dealer form of Katz and its owners Nathan and Benjamin Katz see: https://rkd.nl/en/explore/artists/Katz%2C%20Kunsthandel%20D.

39 On the painting and its provenance, see: https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/objects/800/frans-van-mieris-the-elder-the-doctor’s-visit-dutch-1667.

40 Information kindly provided by Anja Zechel on 31 January 2022.

41 Bernhard Strigel, Sleeping Tomb Guard with mace and sword, circa 1520/21, BStGS - Alte Pinakothek München, URL: https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/gR4kZOQGEe (most recently updated on 20 August 2021).

42 Bambi, “Nicht pinakothekswürdig”, 127.

43 Certainly, the Pinakothek still owns comparable landscapes by Jan Brueghel the Elder today, see online collection: https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/search?phrase=Brueghel#filters={}., so that a case for deaccessioning the Brueghel could be made in principle.

44 Bambi, “Nicht pinakothekswürdig”, 129; Sepp, Ernst Buchner, 241-249.

45 See National Gallery in London: https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/claude-monet-la-pointe-de-la-heve-sainte-adresse.

46 See Minneapolis Institute of Art: https://collections.artsmia.org/art/1163/the-piazza-san-marco-pierre-auguste-renoir.

47 Hans Thoma, Girl feeding chickens, 1870, BStGS - Neue Pinakothek München, URL: https://www.sammlung.pinakothek.de/de/artwork/6kLa6Q9G8V (most recently updated on 12 August 2021).

48 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index Luzern, L_10404.

49 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_36-0221.

50 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_36-0222.

51 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_37-0035.

52 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_37-0036.

53 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_37-0156.

54 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_39-0279.

55 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_39-0280.

56 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_40-0031.

57 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_40-0032.

58 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_40-0035.

59 ZI München/Photothek, Archiv Julius Böhler, card index München, M_40-0036.

60 Sepp, Ernst Buchner, 218. Another example is the museum director Kurt Martin in Strasbourg. He was tasked with expanding the holdings of museums in the Upper Rhine region while at the same time reversing the “undesirable course“ of the past, which had been directed towards French art, by acquiring German masterpieces. See Tessa Friederike Rosebrock, Kurt Martin und das Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. Museums- und Ausstellungspolitik im ‘Dritten Reich‘ und in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag 2012), 113, 124 and 161–163.

61 Bambi, “Nicht pinakothekswürdig”, 126.

62 Johannes Gramlich and Meike Hopp, “Gelegentlich wird Geist zu Geld gemacht“ – Hildebrand Gurlitt als Kunsthändler im Nationalsozialismus, in: Kunstmuseum Bern and Kunsthalle Bonn (eds.), in Bestandsaufnahme Gurlitt (München: Hirmer, 2017), 32–47, here 46.