ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Iñigo Salto Santamaría

The present article aims to study the deaccession and acquisition of a Byzantine artefact today held in the collection at Dumbarton Oaks, an ivory plaque depicting the Incredulity of Thomas. The object’s previous provenance will be examined as well as the interests of the two parties involved in its exchange, as well as the agents entangled in this transaction and its consequences for the collecting strategy of the American buyers, Mildred Barnes Bliss and Robert Woods Bliss. The fate of this Byzantine artifact depicting the incredulity of Thomas shall shed light on the nationalistic policy followed by German museums in the 1930s, as well as on American collecting patterns that took advantage of this policy. The museum and academic character of the Incredulity plaque in the 1930s was rich in contrast. Firstly, it existed as a non-German decorative arts object in a museum that had grown to prioritize German fine arts, where it thus played a minor role. At the same time, this piece had gradually been discussed, displayed and reproduced in groundbreaking publications in the field of Byzantine art, increasingly gaining recognition among scholars. The nationalistic tendencies that only increased after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 would eventually change the Incredulity plaque’s fate as part of the GNM collection.

When I was introduced to Mr. Bliss at Worcester, he took an ivory out of his pocket and asked my opinion. It was a Byzantine plaque representing the Doubting Thomas, and I had seen an absolutely identical plaque in the Germanic Museum in Nürnberg. [...] “This is the piece from Nürnberg,” Bliss told me with a smile.1

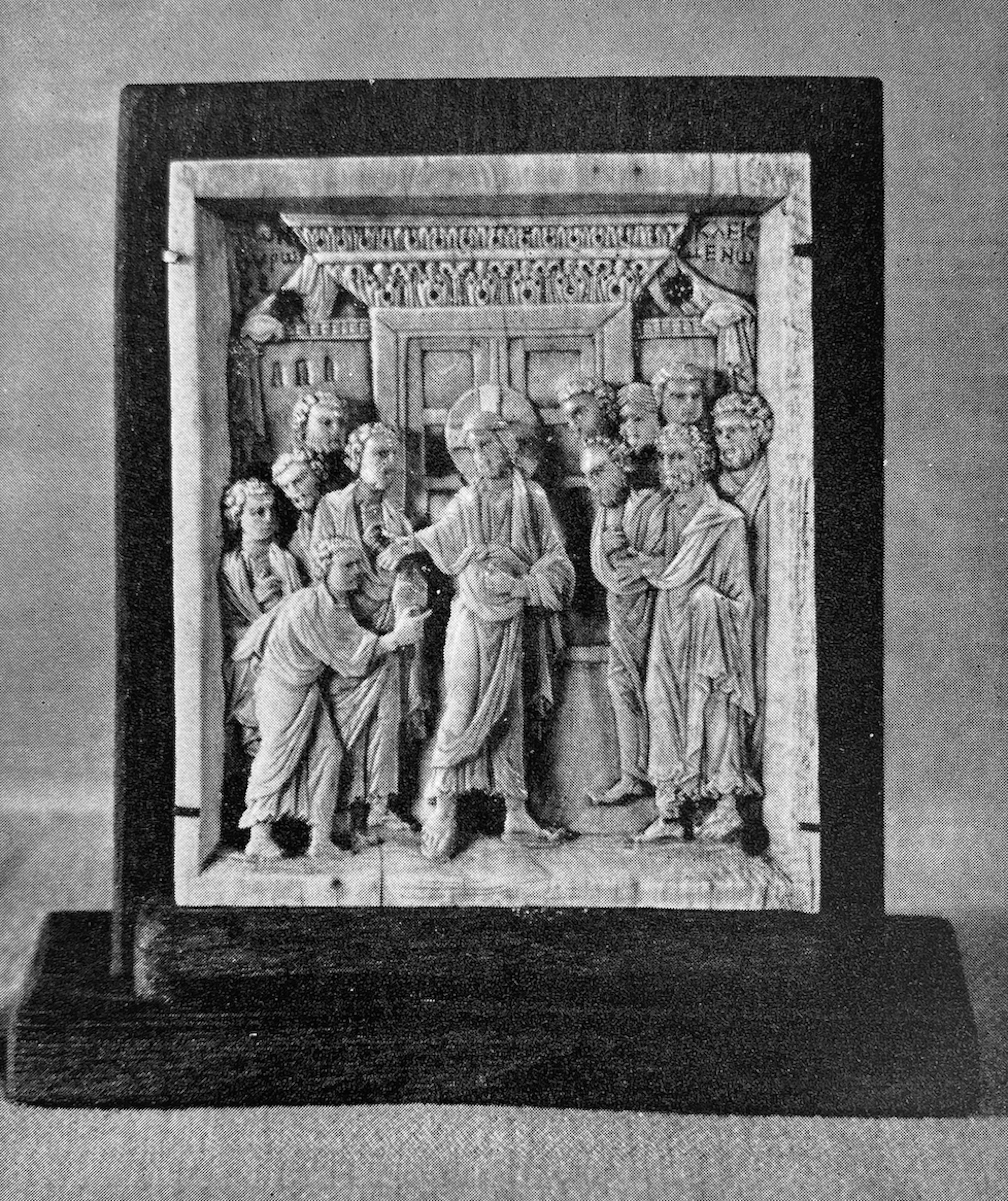

Why would a museum get rid of such a fine object? This question arises when confronted with The Incredulity of Thomas ivory plaque, carved in Constantinople in the tenth century and held today at the Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection in Washington, D.C. (fig.1).2 Before its acquisition in early 1937 by Mildred Barnes Bliss and Robert Woods Bliss, the founders of Dumbarton Oaks, this artwork had belonged to the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (GNM)3 in Nuremberg for more than forty years. This German institution exchanged it for a ninth-century Langobard book chest in May 1936,4 an action that put the Incredulity plaque on the market and allowed its eventual purchase by the abovementioned prominent American collectors.

Fig. 1: Plaque with the Incredulity of Thomas, ivory, 11.43 cm x 8.89 cm, Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, D.C., BZ.1937.7.

© Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

The present article aims to study the deaccession and acquisition of the Nuremberg Ivory as a single phenomenon, looking at the object’s previous provenance, the interests behind the two parties involved in its exchange, as well as the agents entangled in this transaction and its consequences for the Blisses’ collecting strategy. The fate of this Byzantine artifact shall shed light both on the nationalistic policy followed by German museums in the 1930s, as well as on American collecting patterns that took advantage of this policy.

The earliest provenance of The Incredulity of Thomas ivory plaque can be traced to the Spitzer collection in Paris.5 Frédéric Spitzer (1815-1890) was one of the most important art collectors in nineteenth-century Europe, who especially focused on collecting artifacts from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance.6 His eminent assemblage of objects contained, among other treasures, an outstanding stock of 175 medieval ivories ranging from Late Antiquity to the French Gothic.7 Alfred Darcel (1818-1893), director of the Musée de Cluny, cataloged the ivories as part of the publication project led by Émile Molinier (1857-1906).8 Darcel categorized the Incredulity plaque as a twelfth-century Byzantine creation.9

After Spitzer’s death, the bulk of his immense collection of over four thousand artifacts was auctioned in Paris in 1893.10 This sale attracted a plethora of museum officers and dealers keen to enrich their collections. As stated by art historian Paola Cordera, German curators established a sort of protocol of artworks to bid on to avoid competing against each other;11 the Incredulity ivory was included in a wish list comprising the “desirable sculptures of Christian art” in the Spitzer collection.12 Offered on the sale’s fourth day (20 April 1893),13 the ivory was purchased for “circa 1,000 FF”.14 According to the annotations present in the sale catalogue conserved at the Bargello, which are included in Cordera’s catalogue raisonné of the Spitzer collection, this and other pieces bought by German museums seem to have gone through the hands of London dealers Durlacher Bros, 15 who might have bid on behalf of these institutions. The Berlin collection of Byzantine ivory carvings, one of the most important of its kind in Germany, was enriched with a larger plaque depicting the Washing of the Feet.16 Why did the Incredulity ivory not join the same department, the Abteilung der Bildwerke der christlichen Epoche in Berlin as well? The rationale behind the choice to send this piece to the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg and not to the capital is intriguing and could be interpreted as a result of the collaboration among German museums in the context of the Spitzer sale which might have prevented Berlin from monopolizing all ivory carvings.

The ivory plaque’s arrival at the GNM can be described as unceremonious among a large number of acquisitions in 1893.17 Two other Spitzer artifacts also entered the museum’s collection: an “eighth-century” Byzantine ivory comb displayed next to the Incredulity plaque in the sale catalog (fig. 2), now dated to the tenth century,18 and a “Romanesque” bronze candleholder that was later identified as a nineteenth-century forgery.19

The “older” ivory comb was extensively discussed in the museum’s bulletin edition in 1895. In this article, the young curatorial assistant Edmund Braun (1870-1957)20 rejected Darcel’s Byzantine attribution in favor of a North-Alpine, perhaps Merovingian origin, based on “individual national moments” in the object’s iconography, such as the jousting theme and the weapons depicted on the comb.21 The Eastern Roman origin of the Incredulity plaque, unmistakable because of its Greek inscription, hindered any nationalistic appropriation efforts from an institution that, at its core, revolved around German-speaking cultural artifacts and documents.

Founded by Hans von Aufseß (1801-1872) in 1852, the Germanisches Nationalmuseum’s collection had been conceived as a “general repertory of all source materials for German history, literature and art”.22 The “Germanic” and “national” terms in the institution’s name did not refer to a specific political entity, but rather to the whole German-speaking area as a cultural nation.23 The museum originally encompassed objects until the mid-seventeenth century, the moment in which, according to Aufseß, Italian influence on German art got out of hand.24 Interestingly, this nationalistic perspective did not prevent the GNM from owning, displaying and acquiring artifacts created by non-German speaking cultures, starting with Aufseß’s core collection and ranging to the twentieth century. The museum’s only Byzantine ivory relief until the Incredulity plaque’s arrival derived from Aufseß’s original pieces.25 The acquisition of several Limoges pieces in the 1870s-1890s,26 to name an example, demonstrates that the concept that Aufseß envisioned changed over the years, gradually aligning the GNM with other late nineteenth-century museums of decorative arts in its collecting patterns while maintaining its distinct nationalistic focus in its outreach and publications.

Fig. 2: Spitzer ivory sale catalog, detail. No. 68 is the Incredulity plaque; No. 42 is the Nuremberg Byzantine comb.

Catalogue des objets d'art et de haute curiosité antiques, du Moyen-Âge et de la Renaissance composant l'importante et précieuse collection Spitzer, dont la vente publique aura lieu à Paris, Illustration volume (Paris: 1893), plate III, detail.

The Incredulity plaque was likely included in the Christian decorative arts section in room 15, along with other medieval ivory pieces.27 Its integration in the collection came at a pivotal time in the museum’s development. Conceived as a cultural history museum that displayed predominantly medieval artifacts in an immersive architectural setting, the GNM gradually evolved to prioritize the paintings and sculpture departments from the early twentieth century onwards, both from a collecting and a museographical point of view,28 which relegated medieval decorative arts such as the Incredulity ivory to the background. While its original display setting was probably not greatly altered since the beginning of the century, the Incredulity plaque slowly gained attention in German and international academic circles.

The ivory was first included in Walter Josephi’s (1874-1945) 1910 catalog of the museum’s sculpture collection, which dated its creation around the eleventh/twelfth centuries.29 In 1923, Wolfgang Fritz Volbach (1892-1988), curator of Early Christian and Byzantine Art at the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum, was the first scholar to put the Nuremberg piece in relation to the Raising of Lazarus ivory in Berlin, shifting its date to the tenth century.30 Eight years later, the plaque was lent to the first monographic exhibition of Byzantine art in Paris, where it was displayed as an object from the tenth/eleventh century.31 This dating was confirmed by Adolph Goldschmidt (1863-1944) and Kurt Weitzmann (1904-1993) in the second volume of Goldschmidt’s landmark publication Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des XI.-XIII. Jahrhunderts (fig. 3).32

Fig. 3: Reproduction of the Incredulity plaque in Goldschmidt/Weitzmann’s publication, 1934.

Adolph Goldschmidt and Kurt Weitzmann, Reliefs, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X. - XIII. Jahrhunderts, 2 (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1934), plate IV, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.53147#0109, detail.

The museum and academic character of the Incredulity plaque in the 1930s was rich in contrast. Firstly, it existed as a non-German decorative arts object in a museum that had grown to prioritize German fine arts, where it thus played a minor role. At the same time, this piece had gradually been discussed, displayed and reproduced in groundbreaking publications in the field of Byzantine art, increasingly gaining recognition among scholars. The nationalistic tendencies that only increased after Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 would eventually change the Incredulity plaque’s fate as part of the GNM collection.

The 1934 statute of the Germanisches Nationalmuseum confirmed that the institution’s main goal was “to keep and increase the knowledge of the German past”.34 During Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann’s (1886-1971) directorship, which ranged from 1920 until October 1936, the museum’s acquisition policy mainly focused on enriching the painting and sculpture departments, as well as the museum’s eighteenth-century holdings.35 In the 1930s, the nationalistic political turn in Germany drove the GNM’s renewed orientation towards German medieval art.36

This was reflected in the acquisition of a ninth-century Langobard book chest that was offered in auction by Swiss art dealer Theodor Fischer (1878-1957) in 1934.37 Not having found a suitable buyer, Fischer bought the object for 23,000 CHF and subsequently presented it to Zimmermann in May 1935.38 The GNM’s director readily identified the book chest as an unmissable purchase for the museum in Nuremberg, which marked the beginning of a year-long negotiation with the Swiss dealer. Due to Nazi Germany’s strict regulation of foreign currency, the museum’s insufficient stock of Swiss Francs and the favorable conditions that this exchange would be based on with regard to customs, it was clear from the beginning that the book chest would be acquired in exchange for items in the GNM’s collection.39

Deaccessioning objects in transaction for new acquisitions was a common practice in German museums in the early twentieth century.40 Zimmermann himself frequently resorted to this solution to finance acquisitions in Nuremberg, with non-German artifacts often being exchanged.41 These losses were justified by the collection’s growth in first-range objects from a specific category, which in Nuremberg’s case was German art.42

The same procedure was therefore pursued to acquire the Langobard book chest. Not long after having seen the artifact in Lucerne, Zimmermann offered Fischer a seventeenth-century tankard by Swiss artist Hans Heinrich Riva. During a visit to the GNM in the summer of 1935, Fischer inspected the proposed artwork and went through the museum galleries in the company of the Munich dealer Julius Böhler Jr. (1883-1966) in search of other items that might be suitable for exchange.43

The Incredulity of Thomas ivory was probably identified as a target during this visit, since Fischer included it in his new wish list of 6 October 1935, together with the Swiss tankard and a twelfth-century Limoges shrine, possibly St. Saturnin’s reliquary.44 The foreign character of these artifacts was, according to Fischer, the main criterium for his choice, since these pieces did “not really belong in the Germanic Museum and would thus represent no artistic loss for Germany”.45 Fischer alternatively proposed to exchange the book chest for a French tapestry, again mentioning that this artwork “had nothing to do with the Germanic Museum”.46 The blatant language in Fischer’s letters verbalizes the nationalistic attitude towards museum collections in Nazi Germany in general, and at Zimmermann’s GNM in particular, on which the Swiss dealer capitalized to secure a deal. In mid-February 1936, Fischer attached a letter sent to him by Adolf Feulner (1884-1945), curator at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Frankfurt, in which he described the Langobard chest as “an excellent monument of Germanic art that should absolutely come to a German museum”,47 adding pressure to Zimmermann’s decision-making. In the meantime, the museum director had explored different exchange options that included different amounts of money in CHF or RM and an array of objects, including the Incredulity plaque.48

Once Fischer’s urgency had considerably increased in February 1936, Zimmermann corresponded about the Incredulity ivory with Otto von Falke (1862-1942), former director of the Berlin museums until his retirement in 1927. Falke had also been part of the GNM’s administration council since 1915, having been reelected for this role in 1932.49 Outlining Fischer’s requests, Zimmermann expressed his categorical rejection of offering the Limoges’ shrine in exchange and attached a picture of the ivory plaque. Mentioning that it had been on display at the 1931 Byzantine exhibition, Zimmermann implicitly asked Falke for his opinion on this deaccession, which he “would not approve without asking the administrative board”.50 The flat-out rejection of Fischer’s attempt to get his hands on the Limoges shrine in comparison to the feeble reticence to give up the Incredulity ivory is telling with regard to the latter’s position in the GNM’s collection. The requested French piece was one of the most important pieces out of a considerable ensemble of over twenty-five Limoges items.51 In comparison, Byzantine art was scarcely represented in the GNM.

Zimmerman’s request for Falke’s opinion on the ivory may suggest that this piece had been explicitly chosen by Fischer. The GNM’s decision-making consisted in assessing the pertinence of the proposed deaccessions while trying to satisfy Fischer’s requests, which had comprised the Riva tankard and the ivory plaque from an early stage. Falke admitted that deaccessioning the Incredulity plaque was more challenging than giving away the Swiss tankard. According to him, the ivory should be praised for its “self-contained representation”, while accepting that it was not on the same level of “first-class” items such as the Harbaville Triptych at the Louvre.52 Nonetheless, he approved of this exchange, underlining that the acquisition of the Langobard book chest was “a matter of national importance” and that, by exchanging the Swiss tankard and the Incredulity plaque, the GNM reached a good deal. 53

The exchange was unanimously accepted by the museum’s administrative board in March 1936.54 Once the Swiss Foreign Currency Office in Zürich approved the exchange in early April 1936, the transport of the objects to Switzerland was initiated.55 Wilhelm Kahlert (?-1940), a Berlin art dealer specialized in militaria, picked up the objects in Nuremberg on his way to Zürich on 11 May 1936.56 Kahlert’s journey to Switzerland was prompted by the auctions scheduled at the Zunfthaus zur Meise between 13 and 16 May 1936, organized by Fischer himself.57 These sales included antiquities and, according to one catalog cover, “museum property”.58 Although neither the Riva tankard nor the Incredulity plaque are mentioned in the diverse sales catalogs, the artifacts were in Zürich at this time.59

The provenance chain of the Incredulity plaque in the months following May 1936 remain to be determined.60 Fischer’s intentions for this artwork, probably chosen in the company of Julius Böhler during their visit to the GNM in 1935, also remain unclear. Fischer may have considered the ivory, recently published in Goldschmidt and Weitzmann’s landmark book, as an artwork of pedigree (Spitzer, Nuremberg) that could do well on the international market for medieval art. Whatever the artwork’s precise path might have been, the Incredulity plaque appeared in the possession of the Stora Gallery in Paris in late December 1936, when it was shown to the American connoisseur Royall Tyler.61

The deaccession of objects did not only financially enable the pursuit of a nationalistic acquisition policy by German museums such as the Germanisches Nationalmuseum. Furthermore, it paved the way for dealers and art museums outside Germany to enrich their collections with rare and important masterpieces. In 1937, the Met Cloisters in New York acquired a fourteenth-century French Madonna which had been sold by the Berlin museums shortly before.62 That same year, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London purchased Byzantine textile fragments formerly in possession of the Kunstgewerbemuseum Düsseldorf.63 The GNM’s loss of The Incredulity of Thomas ivory enriched the holdings of two prominent American collectors of Byzantine art, socialite Mildred Barnes Bliss (1879-1969) and diplomat Robert Wood Bliss (1875-1962).

The Blisses had ammassed an impressive collection of Byzantine art in the 1920s and early 1930s. Their desire to give their collection and their estate in Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks, to Harvard University began to materialize in the mid-1930s, which prompted them to increase their holdings.64 To do so, the Blisses often resorted to their long-time friend Royall Tyler (1884-1953), an American art historian and diplomat who lived in Europe.65

In November 1936, shortly before seeing the Nuremberg Ivory in Paris, Tyler and the Blisses had been approached about a possible sale of the so-called Goldene Tafel, a Byzantine enamel that belonged to the Bavarian Royal House of Wittelsbach.66 While advising the Blisses to reject this high-priced artwork, Tyler expressed that an opportunity might soon arise to purchase more important artifacts in Germany due to the country’s political situation. He explicitly mentioned the Limburg Staurotheke, a tenth-century reliquary containing first-class cloisonné enamels that he considered “the most important movable Byzantine work in existence”.67

While planning a strategy to inquire about the Staurotheke’s availability, Tyler saw the Incredulity plaque at M & R Stora, a Parisian gallery that specialized in medieval and Renaissance decorative arts.68 In his letter to the Blisses regarding this piece, he mentioned the Incredulity ivory’s relationship to the Lazarus plaque in Berlin and its recent publication in Goldschmidt’s publication and implied that the GNM had sold it “presumably because not Nordic”.69

Fig. 4: Plaque with the Incredulity of Thomas, reverse.

© Dumbarton Oaks, Byzantine Collection, Washington, DC

The Blisses swiftly acquired the ivory from the Storas.70 The French exportation stamp on the back of the Incredulity plaque (fig. 4) is a likely trace of this transatlantic transport measure.71 The object may have passed through the Stora Gallery branch in New York before being delivered to the Blisses. Kurt Weitzmann’s recollection of Bliss showing him the Nuremberg plaque in the context of the “The Dark Ages: Loan Exhibition of Pagan and Christian Art in the Latin West and Byzantine East” show at the Worcester Art Museum may imply that the ivory was already in the United States by February-March 1937.72

The deaccession of the Incredulity plaque by the GNM reinforced Royall Tyler’s view that it was a prime moment to try and purchase Byzantine objects from German museums.73 The Blisses agreed to involve Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, former curator at the Berlin museums, in their ensuing survey of Byzantine artifacts in public collections.74 Volbach had lost his position in Berlin because of the 1933 anti-Semitic Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service and worked at the time at the Vatican’s Museo Cristiano.75 Tyler met Volbach in Rome in February 1937, where they discussed the possibility of inquiring about items such as the Limburg Staurotheke.76 Although objects belonging to the church, such as the Staurotheke, would be difficult to obtain, Volbach deemed the purchase of state-owned artifacts feasible.77 After this meeting, Royall Tyler sent a list of the four “finest Byzantine works of art in German State possession”, according to him and Volbach, to the Blisses:78 two tenth-century ivory plaques formerly forming a diptych, split between the Provinzialmuseum Hannover79 and the Grünes Gewölbe in Dresden (fig. 5);80 the tenth-century Lion Silk at the church of St. Heribert in Cologne-Deutz;81 and the seventh-century Bahram Silk at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin.82

Even if Volbach’s wife and Hermann Göring’s aide-de-camp Philipp von Hessen are mentioned in the correspondence between Tyler and the Blisses as possible intermediaries,83 the middleman in charge of surveying these and other German institutions was Hermann Fiedler (1866-1940), also an acquaintance of Volbach.84 A resident of Ticino, Switzerland since at least 1931, Fiedler seems to have conducted several business affairs in Germany.85 The 70/71-year-old Fiedler was the acting branch of the Blisses’ collecting interests in the following years, with Royall Tyler as an interlocutor for the two involved parties.

Fig. 5: Reproduction of the Hannover and Dresden plaques in Goldschmidt/Weitzmann’s publication, 1934.

Adolph Goldschmidt and Kurt Weitzmann, Reliefs, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X. - XIII. Jahrhunderts, 2 (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1934), plate XVII, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.53147#0135, detail.

Fiedler’s most notable triumph was the acquisition of two Byzantine stone reliefs in the collection of Prince Friedrich Leopold of Prussia (1895-1959), which were kept at Glienicke Palace near Berlin.86 The correspondence between Tyler and the Blisses reveals that, other than these successful purchases for Dumbarton Oaks, Fiedler negotiated with several German museums and institutions to obtain objects for the Blisses. After the rejection of the Lion Silk at Cologne-Deutz, Fiedler focused his efforts on several ivory plaques.87

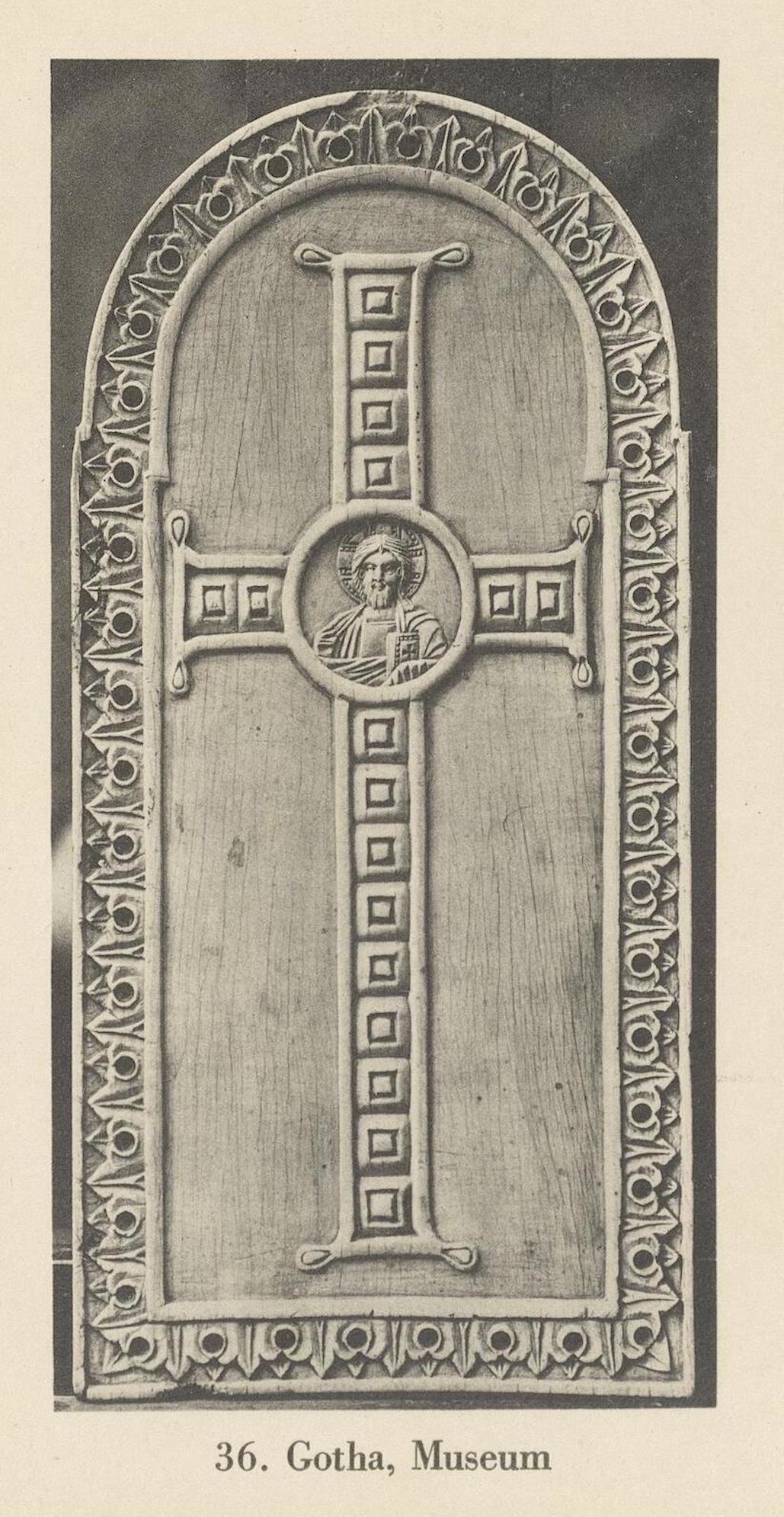

Obtaining the abovementioned Hanover-Dresden pieces, “the very finest of their sort”,88 as well as an ivory plaque from the museum in Gotha89 (fig. 6) were Fiedler’s main goals. This latter piece became increasingly interesting for the Dumbarton Oaks collection after the acquisition of its pendant, formerly in the Fiorentini collection in Lucca, through the dealer Adolph Loewi (1888-1977) in April 1937.90 Between September 1937 and August 1939, in parallel to the Glienecke relief’s acquisition, Fiedler traveled many times to Germany and negotiated with Dresden, Hanover and Gotha officials regarding these and other pieces.91

The difficulties that prolonged these negotiations seem to have been manifold, from a previous sale that made Gotha officials reticent to deaccession, to property-related issues related to the Hanover plaque.92 Although Tyler’s letters often stated that these transactions were about to be completed, none of the items in question had been purchased by the Blisses by September 1939 when the Second World War broke out. The conflict and Fiedler’s passing in April 1940 brought an end to these impressive efforts to acquire deaccessioned objects.93

Future research at archives in the German institutions involved may reveal more details on the negotiations with Fiedler. The correspondence between Tyler and the Blisses discloses the potential that these American collectors saw in Germany’s political panorama, a volatile situation that could allow unprecedented purchases of great significance. In comparison with other artifacts in French and Italian collections mentioned by Tyler which would not become “unstuck”,94 the years immediately before the war demonstrated that a deaccession of actual masterpieces belonging to German museums was possible. The exchange and acquisition of the Nuremberg ivory can be considered a deciding factor in the Blisses’ hunt for Byzantine artifacts in German public collections.

Fig. 6: Reproduction of the Gotha plaque in Goldschmidt/Weitzmann’s publication, 1934.

Adolph Goldschmidt and Kurt Weitzmann, Reliefs, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X. - XIII. Jahrhunderts, 2 (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1934), plaque XIV, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.53147#0129, detail.

The deaccession and purchase of the Nuremberg Ivory bears witness to the tumultuous state of German museums in the years leading up to the Second World War. One may argue that the Incredulity plaque never truly fit in with the Germanisches Nationalmuseum’s mission, and that Fischer cleverly identified the artifact’s potential attractiveness to foreign collectors. The fascinating survey process to enrich the Bliss collection capitalizing on German public collections that ensued, which saw limited but decisive success regarding the Glienecke reliefs, reveals an opportunism that often paves the way of objects into museums. Tyler’s letters to the Blisses evoke a plethora of ever-changing collecting opportunities in pre-war Nazi Germany:

There are superb painted MSS in Vienna—but so far the attitude as to things in the Libraries has been negative. Curious, when the museums, which one would think would attract more attention... [...] Who knows, the Libraries’ turn may come too. And the Churches. One remembers Limburg. And Aachen. And Deutz.95

Five months after Royall Tyler wrote those lines, Germany invaded Poland, beginning a war that would end all further purchasing possibilities discussed in this article. The conflict would also occasion the loss of one of the four “finest” Byzantine pieces listed by Tyler and Volbach in April 1937: the Bahram Silk at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin, which has been missing since 1945.96

While the negotiations between the Blisses, Tyler, Fiedler and several German museums played out between Washington D.C. and Europe, the Incredulity plaque was integrated into the Dumbarton Oaks collection (fig. 7). Between February and March 1940, weeks before the invasion of France and the Low Countries, the ivory plaque was put on display at the loan exhibition Arts of the Middle Ages in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, along with the Lucca ivory plaque and other recent acquisitions by the Blisses. The plaque’s previous owner (“Formerly in the German Museum in Nuremberg”) was mentioned in the 1940 catalog.97 In contrast, the 1946 Dumbarton Oaks collection handbook only referred to the artifact’s Spitzer provenance,98 perhaps wanting to avoid a city name so closely related to the horrors of the past war and the contemporary trials. Today, the provenance section of the artwork’s online entry attests to this spectacular deaccession and purchase actions, which allow present-day visitors and scholars alike to admire the Incredulity of Thomas ivory at Dumbarton Oaks.

Fig. 7: The Incredulity plaque’s display device at Dumbarton Oaks, 1946.

The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection of Harvard University: Handbook of the Collection (Washington, D.C.: 1946), 86, illustration no. 158.

Iñigo Salto Santamaría is a PhD student at Technical University in Berlin where he is working on a thesis entitled “The Middle Ages at War. Display of Medieval Art in a Transatlantic Context during the World War II Era (1930-1955)". His research is funded by the German National Academic Foundation (Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes).

1 Kurt Weitzmann, Sailing with Byzantium from Europe to America: The Memoirs of an Art Historian (Munich: Editio Maris, 1994), 121.

2 Accession Number BZ.1937.7, http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/27446. All links in this article were accessed on 22 April 2022.

3 For a historical overview of the museum’s name and the coexistence of the forms “Germanisches Nationalmuseum” and “Germanisches Museum”, see: Jutta Zander-Seidel, ‘Drum ist das germanische Museum ein National-Museum’: Namensgebung und Namensverständnis, in Jutta Zander-Seidel and Anja Kregeloh, eds., Geschichtsbilder: Die Gründung des Germanischen Nationalmuseums und das Mittelalter (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2014), 56-65.

4 Accession Number KG1133, http://objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/KG1133. On the acquisition of the Langobard book chest, see: Anja Ebert, Im Tausch erworben, in Anne-Cathrin Schreck, Anja Ebert and Timo Saalmann, eds., Gekauft – Getauscht – Geraubt? Erwerbungen zwischen 1933 und 1945 (Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2019), 80-85, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.392.

5 La collection Spitzer, Antiquité, Moyen-Age, Renaissance (Paris: Macon, 1890), 34, no. 33, https://archive.org/details/Spitzer1/page/n43/mode/2up.

6 On Frédéric Spitzer and his collection, see: Paola Cordera, La fabbrica del Rinascimento: Frédéric Spitzer mercante d’arte e collezionista nell’Europa delle nuove Nazioni (Bologna: Bononia University Press, 2014).

7 Paola Cordera, Art for Sale and Display: German Acquisitions from the Spitzer Collection ‘Sale of the Century’, in Lynn Catterson, ed., Florence, Berlin and Beyond: Late Nineteenth-Century Art Markets and their Social Networks, Studies in the History of Collecting & Art Markets, 9 (Leiden-Boston: Brill, 2020), 121, https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004431041_006.

8 Agnès Bos, Émile Molinier, The ‘Incompatible’ Roles of a Louvre Curator, in Journal of the History of Collections 27/3 (2015), 311, https://doi.org/10.1093/jhc/fhu075.

9 La collection Spitzer, 34, no. 33, https://archive.org/details/Spitzer1/page/n43/mode/2up.

10 Cordera, Art for Sale and Display, 127.

11 Ibid., 136.

12 ‘Verzeichniß der für die Abtheilung der christlichen Bildwerke wünschenswerthen Gegenstände der Sammlung Spitzer’, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv, I/SKS 67.

13 Résumé du Catalogue des objets d’art et de haute curiosité antiques du moyen-age et de la Renaissance composant l’importante et précieuse collection Spitzer dont la Vente publique aura lieu à Paris du lundi 17 avril au Vendredi 16 Juin 1893 (Paris: Imprimerie de l’art, 1893), 15, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k373969c/f16.item. The Incredulity plaque was offered as a twelfth century Byzantine object: Ibid, 31, no. 68, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k373969c/f32.item.

14 I am grateful to Dr. Markus T. Huber and Melanie Haase (Germanisches Nationalmuseum) for allowing me to access the Incredulity plaque’s object registry card which includes this information.

15 Paola Cordera, La fabbrica del Rinascimento: Frédéric Spitzer mercante d’arte e collezionista nell’Europa delle nouve nazioni (Bologna: Bologna University Press, 2014), 161(1893/68, Nuremberg Incredulity ivory), 206 (I/33, Berlin Washing of the Feet ivory, http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=1609294&viewType=detailView ) and 218 (IV/3, Nuremberg candleholder, https://objektkatalog.gnm.de/wisski/navigate/72537/view). On Durlacher and Bros: Durlacher Bros, The British Museum entity record, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG68784.

16 Accession Number Ident.Nr. 2108, http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=1609294&viewType=detailView.

17 Zuwachs der Sammlungen, in Anzeiger des germanischen Nationalmuseums 3 (1893), 33. The Incredulity plaque’s accession number at the GNM was Pl.O. 477.

18 Accession Number KG829, http://objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/KG829. Résumé du Catalogue, 29, no. 42, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k373969c/f30.item.

19 Accession Number KG724, http://objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/KG724. Résumé du Catalogue, 92, no. 969, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k373969c/f93.item.

20 On Edmund Wilhelm Braun, see: Prof. Dr. E. W. Braun 85 Jahre alt, in Weltkunst 25 (1955), 2.

21 Edmund Braun, Ein frühmittelalterlicher Elfenbeinkamm im germanischen Museum, in Mitteilungen aus dem Germanischen Nationalmuseum, 11 (1895), 88, https://doi.org/10.11588/mignm.1895.0.27743.

22 Jutta Zander-Seidel, Das Germanische Nationalmuseum und das Mittelalter, in Mittelalter, Kunst und Kultur von der Spätantike bis zum 15. Jahrhundert, Die Schausammlungen des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2 (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2007), 11.

23 Zander-Seidel, Namensgebung, 57. On the museum’s foundation and its political context, see also: Irmtraud Freifrau von Andrian-Werburg, Das Germanische Nationalmuseum: Gründung und Frühzeit (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2002), especially 7-13.

24 Zander-Seidel, Das Germanische Nationalmuseum, 11.

25 Accession Number Pl.O.475, http://objektkatalog.gnm.de/objekt/Pl.O.475.

26 Mittelalter, Kunst und Kultur von der Spätantike bis zum 15. Jahrhundert, Die Schausammlungen des Germanischen Naitonalmuseums, 2 (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2007), 411-414.

27 Führer durch die Kunst- und Kulturgeschichtlichen Sammlungen, Germanisches Museum (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Museums, 1925), 50: “Neben den Metallarbeiten enthält die Vitrine auch einige bedeutsame Proben alter Elfenbeinschnitzkunst...”. The Incredulity ivory is not explicitly mentioned in this guide.

28 Zander-Seidel, Das Germanische Nationalmuseum, 18-19.

29 Walter Josephi, Die Werke plastischer Kunst im Germanischen Nationalmuseum Nürnberg (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Museums, 1910), 355, no. 618, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.54665#0369.

30 Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, Die Elfenbeinbildwerke, Die Bildwerke des Deutschen Museums, 1 (Berlin/Leipzig: Walter De Gruyter & Co, 1923), 12, J. 578. On the Raising of Lazarus plaque: Accession Number 578, Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, http://www.smb-digital.de/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=1409067&viewType=detailView.

31 Exposition internationale d’art byzantin, exh. cat., Musée des arts décoratifs (Paris: 1931), 77, no. 103, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.19211#0091.

32 Adolph Goldschmidt and Kurt Weitzmann, Reliefs, Die byzantinischen Elfenbeinskulpturen des X. - XIII. Jahrhunderts, 2 (Berlin: Bruno Cassirer, 1934), 28, no. 15, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.53147#0034.

33 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, 22 May 1935, GNM-HA (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Historisches Archiv), A-447.

34 ‘Satzung des Germanischen Museums’, §1, GNM-HA, 761.2.

35 Rainer Kahsnitz, Die Kunst der mittelalterlichen Kirchenschätze und das bürgerliche Kunsthandwerk des späten Mittelalters, in Bernward Deneke and Rainer Kahsnitz, eds., Das Germanische Nationalmuseum 1852-1977, Beiträge zu seiner Geschichte (Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1978), 750.

36 Hans-Ulrich Thamer, Autonomie, Selbstmobilisierung und politische Intervention: Museen im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland, in Luitgard Sofie Löw and Matthias Nuding, eds., Zwischen Kulturgeschichte und Politik: Das Germanische Nationalmuseum in der Weimarer Republik und der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus (Nuremberg: Verlag des Germanischen Nationalmuseums, 2014), 20.

37 Ebert, Im Tausch erworben, 82.

38 Ibid.

39 Ibid. For a legal overview on importation and customs into 1930s Switzerland, see: Esther Tisa Francini, Anja Heuss and Georg Kreis, Fluchgut-Raubgut: Der Transfer von Kulturgütern in und über die Schweiz 1933-1945 und die Frage der Restitution (Zürich: Chronos, 2001), especially 56-62.

40 The profuse use of the words “Tausch” and “Verkauf” in the Berlin State Museums archive’s pre-1945 finding aids shows to what extent deaccession and exchange belonged to these institution’s routine. See: Finding aids, Geschäftsakten der Königlichen bzw. Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin bis 1945, https://www.smb.museum/museen-einrichtungen/zentralarchiv/bestaende/uebersicht-und-findbuecher/geschaeftsakten-bis-1945/.

41 For example, two Siculo-Arabic pyxides were sold in the mid-1920s, and later arrived in the collection of the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore; Kahsnitz, Die Kunst, 750-751. See also: Accession Number 71.311, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/13411/cylindrical-box-pyxis/; Accession Number 71.314, https://art.thewalters.org/detail/23356/.

42 Kahsnitz, Die Kunst, 750.

43 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, 5 October 1935, GNM-HA, A-447. See also: Ebert, Im Tausch erworben, 83.

44 Accession Number KG674, https://objektkatalog.gnm.de/wisski/navigate/40584/view. Fischer referred to the desired shrine as “die grosse Limusiner Chasse”, and KG674 is the GNM’s largest Limoges shrine. For an overview of the museum’s Limoges holdings and their dimensions: Mittelalter, Kunst und Kultur, 411-414.

45 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, 5 October 1935, GNM-HA, A-447.

46 Ibid. “[...] als ich mit Herrn Böhler nochmals durchs Museum ging, habe ich im Saale 5 hoch über einem Schrank hängend eine schlecht erhaltene franz. Tapisserie mit Darstellung von Liebespaaren im Freien gesehen. Die Tapisserie ist irrtümlicherweise als burgundisch bezeichnet, aber sie ist unbedingt Nordfranzösisch und fast sicher Arras”. The author of this article has been unable to identify the tapestry in the online catalog of the GNM.

47 Adolf Feulner to Theodor Fischer, 14. Feb 1936, GNM-HA, A-447.

48 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, 29 November 1935, 20 Dez. 1935, A-447.

49 List of members of the GNM’s administrative board, 1936 (?), GNM-HA, 761.4.

50 Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann to Otto von Falke, 22 February 1936, GNM-HA, 761.4.

51 Mittelalter, Kunst und Kultur, 411-414.

52 Otto von Falke to Ernst Heinrich Zimmermann, 4 March 1936, GNM-HA, 761.4. On the Harbaville Tripytich: accession number OA 3247, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark:/53355/cl010112515.

53 Otto von Falke to Ernst Heinrich Zimmernmann, 4 March 1936, GNM-HA, 761.4.

54 ‘Protokoll der Sitzung des Beirates des Verwaltungsrates des Germanischen Museums’, 9 March 1936, GNM-HA, 761.4.

55 Theodor Fischer to Ernst Heinrich Zimmernann, 2 April 1936, GNM-HA, A-447.

56 Wilhelm Kahlert to Ernst Heinrich Zimmernann, 7 May 1936, GNM A-447. On E. Kahlert & Sohn Hofantiquare: Timo Saalmann, Ein Jagdpokal aus Weimar, in Anne-Cathrin Schreck, Anja Ebert and Timo Saalmann, eds., Gekauft – Getauscht – Geraubt? Erwerbungen zwischen 1933 und 1945 (Heidelberg: arthistoricum.net, 2019), 156-159, https://doi.org/10.11588/arthistoricum.392.

57 Grosse Auktion in Zürich (Lucerne: Galerie Fischer, 1937), https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.7111#0001.

58 Ibid.

59 The tankard was eventually acquired by the Landesmuseum in Zürich. accession number LM-20424, https://sammlung.nationalmuseum.ch/de/list?searchText=riva&detailID=100081291.

60 The ivory plaque arrived in Switzerland in May 1936 and was in the possession of the Stora Gallery in Paris in late December 1936. It remains to be determined whether the Storas purchased the ivory directly from Fischer, or if the plaque passed through other hands in the meantime.

61 Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 23 December 1936, Bliss-Tyler correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/23dec1936. The original letters between the Blisses and Tyler is kept at the Harvard University Archives, HUGFP 38.6, boxes 1–5. Henceforth, the indication “Bliss-Tyler Correspondence” alludes to these materials and their transcriptions, searchable under https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence.

62 Accession number 37.159, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/472389.

63 Accession number T.93-1937, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O230789/textile-fragments-unknown/. See also: Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 25 July 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/25jul1937.

64 James N. Carder, Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss: A Brief Biography, in: James N. Carder, ed., A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010), 13-14.

65 Robert S. Nelson, Royall Tyler and the Bliss Collection of Byzantine Art, in: James N. Carder, ed., A Home of the Humanities: The Collecting and Patronage of Mildred and Robert Woods Bliss (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010), 27-28.

66 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 6 November 1936, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/06nov1936-2. On the Goldene Tafel: Rom und Byzanz: Archäologische Kostbarkeiten aus Bayern, exh. cat., Prähistorische Staatssammlung München (Munich: 1998), 144-145, no. 30. The Goldene Tafel had been offered in 1934 to William M. Milliken, director at the Cleveland Museum of Art, which was discussed by Tyler and the Blisses: Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 25 September 1934, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/25sep1934-1.

67 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 20 December 1938, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/20dec1938

68 On the Stora Gallery, see: M. and R. Stora, Paris and New York, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/annotations/m-and-r-stora-paris-and-new-york; R. Stora and Company, Archives Directory for the History of Collecting in America, https://research.frick.org/directory/detail/1576.

69 Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 23 December 1936, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/23dec1936.

70 The initially proposed price amounted to 15,000 CHF. The usage of Swiss Francs for this transaction could mean that the Storas purchased the ivory directly in Switzerland, perhaps directly from Fischer. Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 23 December 1936, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/23dec1936.

71 The Incredulity plaque was exported out of France twice, in 1893 after the Spitzer sale, and in 1937 after it was acquired by the Blisses. The ivory was also in France during the 1931 Byzantine exhibition. The rooms at the Musée des arts décoratifs were constituted as an “entrepôt réel de douanes”, which avoided customs and allowed to open and close the shipment cases in the museum (see: Curator at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs [no signature] to General Director of French Customs in Le Havre, 23 April 1931, Archives de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, D1-183). It is therefore likely that the exportation label bears witness to the object’s last transport.

72 Weitzmann, Sailing with Byzantium, 121. Also see: The Dark Ages: Loan Exhibition of Pagan and Christian Art in the Latin West and Byzantine East, exh. cat., Worcester Art Museum (Worcester: 1937), https://archive.org/details/darkagesloanexhi00worc/mode/2up.

73 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 7 January 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/07jan1937.

74 Ibid.

75 Elisabeth Ehler, Cäcilia Fluck and Gabriele Mietke, Wissenschaft und Turbulenz: Wolfgang Fritz Volbach, ein Wissenschaftler zwischen den beiden Weltkriegen (Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2017), 12.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.

79 Accession number: WM XXIa, 44b (today Landesmuseum, Hannover). I am grateful to Dr Claudia Andratschke and Dr Antje-Fee Köllermann (Landesmuseum Hannover) for pointing me to the object’s accession number. On the Hanover ivory plaque: Ferdinand Stuttmann, Der Reliquienschatz der goldenen Tafel des St. Michaelisklosters in Lüneburg (Berlin: Verlag für Kunstwissenschaften, 1937), 35-38, no. 1; Jörg Richter, Die Welt im Schatz. Elfenbein und Bergkristall, Straußeneier und Kokosnuss in St. Michaelis, p-128-137. Katalog: p. 151-153. Price proposed by Hermann Fiedler (see note 77): USD 70,000 (including the Dresden plaque, see note 73).

80 Accession number II 51, https://skd-online-collection.skd.museum/Details/Index/117259. On the Dresden ivory plaque: Jutta Kappel, Elfenbeinkunst im Grünen Gewölbe zu Dresden: Geschichte einer Sammlung: wissenschaftlicher Bestandskatalog: Statuetten, Figurengruppen, Reliefs, Gefässe, Varia (Dresden: Sandtstein, 2017), 41-43, I.1. Price proposed by Hermann Fiedler (see note 77): USD 70,000 (including the Hannover plaque, see note 72).

81 On the Lion Silk, see: Doris Oltrogge and Annemarie Stauffer, Diversorum colorum purpura: Neue Forschungen zu der Löwenseide in St. Heribert, in Die kostbaren Hüllen der Heiligen – Textile Schätze aus Kölner Reliquienschreinen: Neue Funde und Forschungen, Colonia Romanica: Jahrbuch des Fördervereins Romanische Kirchen Köln e.V., 31 (2016), 23-32. Price proposed by Hermann Fiedler (see note 77): USD 25,000.

82 Accession number 1878,630 (missing). On the Berlin Bahram Silk: Otto von Falke and Julius Lessing, Die Gewebe-Sammlung des Königlichen Kunstgewerbe-Museums (Berlin: Wasmuth, 1913), Tafel 27-28, https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.18967#0057; Lothar Lambacher, Alexander Schnütgen, Köln (1843-1918), Die Textilien des Domkapitulars, in Peter Keller, ed., Glück, Leidenschaft und Verantwortung: Das Kunstgewerbemuseum und seine Sammler (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1996), 25-26.

https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/gewebesammlungkkmbd1/0057.

83 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 1 March 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/01mar1937. See also: Nelson, The Bliss Collection, 42.

84 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 6 April 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/06apr1937.

85 The documents at the Swiss Federal Archives in Bern contain information about Hermann Fiedler, including an investigation report on Fiedler’s activities in Germany instigated by the Berlin police in 1942. Swiss Federal Archives, P051553.

86 Accession number BZ.1937.23, http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/27169 and accession number BZ.1938.62, http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/35729. On this affair, see: Nelson, Bliss Collection, 42. See also: Gerd-H. Zuchold, Geschichte und Bedeutung eines Bauwerkes und seiner Sammlung: Der “Klosterhof” des Prinzen Karl von Preussen im Park von Schloss Glienicke in Berlin, 1, Die Bauwerke und Kunstdenkmäler von Berlin, 20 (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 1993), 71-72.

87 German Ivories, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/annotations/german-ivories. Other than the ivories named in the main text, it seems that the Lazarus plaque in Berlin (see note 26) was offered to Tyler via a Rome dealer named Borelli/Borely for ITL 70,000. See: Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 5 July 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/05jul1937.

88 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 25 July 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/25jul1937.

89 Accession Number Z.V. 2388. On the Gotha ivory: Goldschmidt and Weitzmann, Reliefs, 36, no. 36., https://doi.org/10.11588/diglit.53147#0042.

90 Accession number BZ.1937.18, http://museum.doaks.org/objects-1/info/27013. See also: Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 9 April 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/09apr1937-1. See also: Nelson, The Bliss Collection, 42-43.

91 Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 4 September 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/04sep1937.

92 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 26 June 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/26jun1937, and Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 4 September 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/04sep1937.

93 Royall Tyler to Mildred Barnes Bliss, 18 May 1940, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/18may1940.

94 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 20 December 1937, Bliss-Tyler Correspondence, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/20dec1937.

95 Royall Tyler to Robert Woods Bliss, 1 May 1939, https://www.doaks.org/resources/bliss-tyler-correspondence/letters/01may1939-1. In this letter, Tyler mentions the annexation of Austria to the German Reich to highlight that items in Austrian collections might become available too. In his last sentence, he refers to the treasures held in Limburg (Limburg Staurotheke), Cologne-Deutz (Lion Silk) and the Aachen Cathedral Treasury.

96 I am grateful to Manuela Krüger (Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin) for this information. According to Erich Meyer, curator at the time, 90% of the textile collection at the Kunstgewerbemuseum was lost during the war, see: Barbara Mundt, Museumsalltag vom Kaiserreich bis zur Demokratie: Chronik des Berliner Kunstgewerbemuseums, in Petra Winter, ed., Schriften zur Geschichte der Berliner Museen, 5 (Cologne: Böhlau, 2018), 416.

97 Arts of the Middle Ages, exh. cat., Museum of Fine Arts (Boston, 1940), 40, no. 116.

98 The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection of Harvard University: Handbook of the Collection (Washington, D.C.: 1946), 78, no. 158.