ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Megan E. O’Neil and Mary E. Miller

This paper addresses the Stendahl Art Galleries’ expansion of their trade in pre-Hispanic art from their home-base in Hollywood to New York and Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s. After an initial success in acquiring and selling ancient Mexican artworks in the early 1940s, the gallery, founded by Earl Stendahl, experienced leaner years in the late 1940s. But they found renewed success after 1950 by placing family members in distinct locations – in Mexico and Central America, to acquire pieces, and in Los Angeles and New York, to cultivate buyers – and by organizing exhibitions in the US and Europe, for which host museums received commissions for sales. What began as works sold one at a time from the Los Angeles gallery would become a network of looters, agents, and buyers that expanded across the US and into Europe, selling both high-priced and inexpensive items in order to capture a broader market. Over the years, they also expanded their sources of pre-Hispanic art, beginning in Mexico and later moving to Panama, Costa Rica, and other countries. This article analyzes letters exchanged among Stendahl family members and clients to shed light on both their acquisistions and sales.

This paper addresses the Stendahl Art Galleries’ expansion of their trade in pre-Hispanic art from their home-base in Hollywood to New York and Europe in the late 1950s and early 1960s.1 After an initial success in acquiring and selling ancient Mexican artworks in the early 1940s, the gallery, founded by Earl Stendahl, faced challenges in the late 1940s. But they found renewed success after 1950 by placing family members in distinct locations – in Mexico and Central America (to acquire pieces) and in Los Angeles and New York (to cultivate buyers) – and by organizing exhibitions in the US and Europe, for which host museums received commissions for sales. They developed an international network of looters, agents, and buyers, involving works of varying sizes and quality that were offered for a range of prices, from inexpensive ceramic figurines to pricey large-scale stone sculptures.

Much of the business took place through personal contacts and outreach, especially by patriarch Earl, but exhibitions organized by the family in the US and Europe, including a mid-century tour of European museums, 1958-60, were one strategy for the gallery to advertise wares, gain clients, increase revenue, and contribute to their commercial success. Through the European tour, the sort of relationships that the Stendahls had established with buyers in the US would be transplanted to the European continent. Earl Stendahl and his family members would return to develop those opportunities for more than a decade.

The gallery obtained their wares from suppliers in countries of origin, including Mexico, Panama, and Costa Rica, which were mostly items without archaeological provenance. Once stripped of archaeological context, these objects were promoted in various ways – as works of art, educational tools, or home decorations – and specifically marketed to art museums and individual collectors. The display of looted objects for sale alongside ones either from archaeological contexts and in Mexican national collections or ones that had resided in Europe for centuries undoubtedly helped to legitimize the commercialized objects as well as the Stendahls, their sellers. The museums that hosted the exhibitions, or those that purchased or received objects as donations, contributed to this market, highlighting the intertwined nature of museums and the market mid-century.

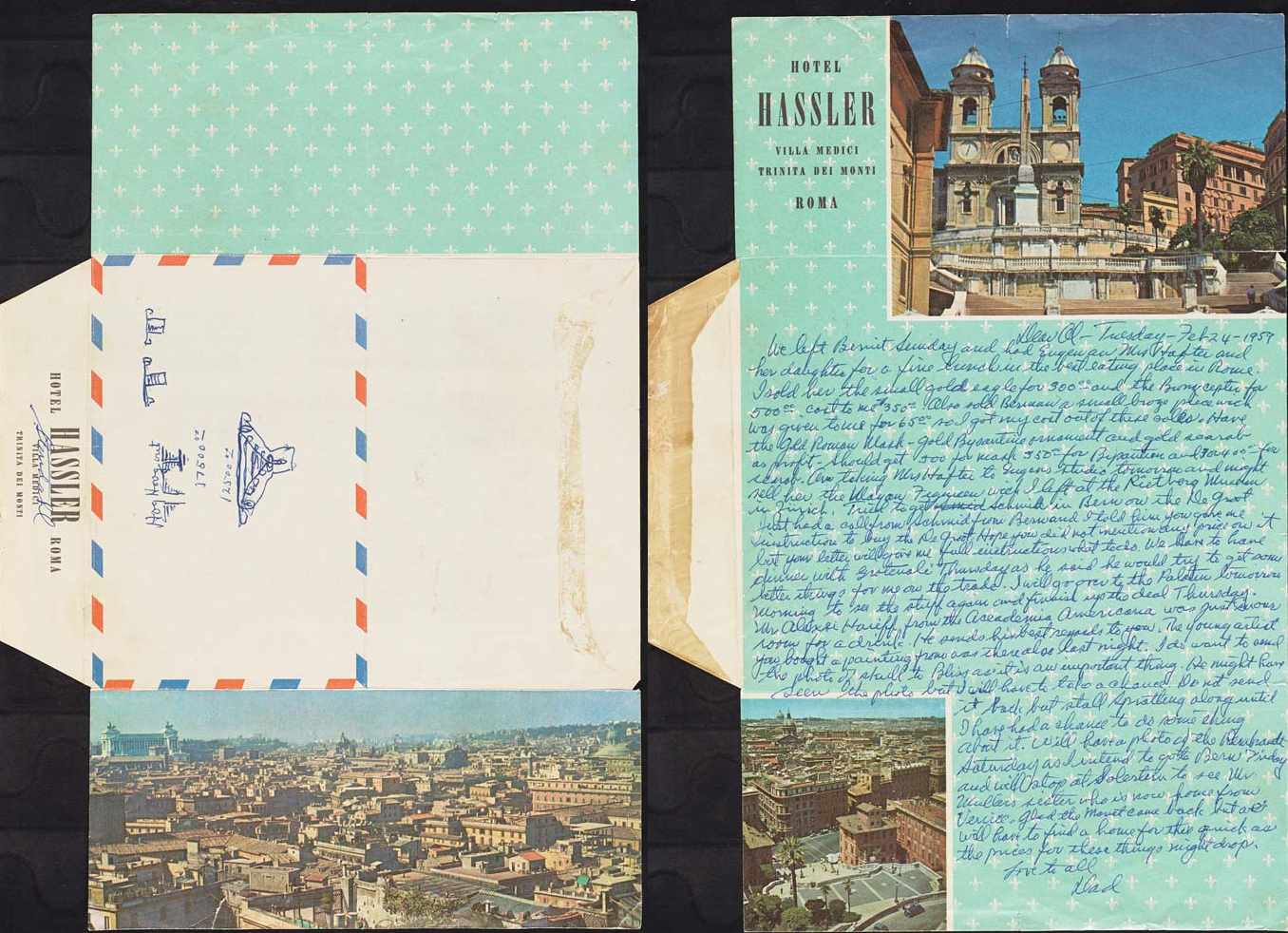

When separated geographically, the family members wrote detailed correspondence, revealing strategies to acquire and sell works, cultivate new clients, and develop a multinational business.2 (Fig. 1) Our collective research derives from those family letters and other documents in the Stendahl Art Galleries Records at the Getty Research Institute (GRI), and from archives at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, the Pierre Matisse Gallery Archives at the Morgan Library, and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), among other archives. This is preliminary research, both in the GRI archives and even more so in the potential intersections, but we outline here the intentions of the Stendahls to grow the business in Europe, as they had in the United States, expanding relationships with both museums and private collectors.

Fig. 1: Letter from Earl Stendahl to Alfred Stendahl, 24 February 1959, Box 105, folder 6, Stendahl Art Galleries Records. Gift of April and Ronald Dammann. Getty Research Institute, 2017.M.38 (hereafter SAG, GRI).

Earl Stendahl founded the Stendahl Art Galleries in Los Angeles in 1911, selling European and American paintings.3 He added pre-Hispanic art in the late 1930s, partly through collaborations with Pierre Matisse in New York City. Matisse also was diversifying his business by working with Parisian dealer Charles Ratton, who loaned exhibitions of non-European art generally and consigned him pre-Hispanic artworks more specifically, including items from the collection of exiled Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz, who died in Paris in 1915.4 Stendahl and Matisse were following other dealers in New York, including Marius de Zayas and the Brummer Gallery, in carrying pre-Hispanic art.5 Stendahl also unsuccessfully solicited pre-Hispanic objects from Mexican artist Diego Rivera.6 But more than any other dealer, Stendahl had his finger on the pulse of the market: he would soon surpass both Ratton’s and Matisse’s abilities to acquire pre-Hispanic art by collaborating with Mexican book and antiquities dealer Guillermo Echániz.7 Their relationship was challenged early on, when Echániz sold Stendahl allegedly ancient Zapotec urns that were quickly recognized to be modern forgeries. The two men continued to work together to locate existing collections for purchase or to extract pieces from the ground, which they illicitly removed from Mexico and brought into the US. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2: Stendahl Art Galleries, c. 1942, box 108, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

In one of his early and most specific attempts to set up a “New York” branch of the business, Stendahl arranged for Karl Nierendorf, who dealt in European modern art in Germany before his immigration to New York,8 to promote inventory in 1940. Through that collaboration, Stendahl hoped to take advantage of the interest generated by Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art, an exhibition that year at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, organized by the Mexican government and Nelson Rockefeller, and including pre-Hispanic, colonial, modern, and folk art from Mexico, establishing a pattern that would be repeated in Mexican exhibitions going forward.9 Correspondence between Stendahl and Nierendorf or with Echániz brings to light the dubious inventory sold by Echániz.10 Nierendorf’s fury about the forgeries helps reveal the range of works for sale in the US and Mexico in 1940, from forgeries to pastiches to monumental works pried from walls and dug from the ground. It was also in this moment that the archaeological community in and around New York became more keenly aware of the trade and traffic in pre-Hispanic art – and often assisted dealers and collectors. George Vaillant, perhaps the most prominent archaeologist of the region and a close colleague of Alfonso Caso, Director of Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), spotted the fakes but also advised Robert Woods Bliss, who would go on to form the most important private collection of pre-Hispanic art in the two decades after World War II. The relationship of curators to collectors and dealers would become even more explicit with subsequent American Museum of Natural History curators, Gordon Ekholm and Junius Bird, who routinely assessed works for André Emmerich, among other dealers.11

In the early 1940s, Stendahl and Echániz worked together to smuggle murals from the Tetitla and Atetelco residential complexes at the archaeological site of Teotihuacan and into the US. Stendahl sold one mural to Bliss for $10,000 US dollars, more than forty times what Stendahl had paid for it.12 Success at Teotihuacan propelled the men’s business relationship forward, and especially as the European art market suffered because of World War II. In collaboration with Echániz, Stendahl found great success in smuggling pre-Hispanic art into the US and building new clientele, outmaneuvering Matisse and outlasting Brummer. But with new INAH oversight in the environs of Teotihuacan and pressure from Mexican journalists, they sought inventory elsewhere.13

A major source of their antiquities by the 1940s was West Mexico, generally understood to comprise the states of Jalisco, Nayarit, and Colima. US consular invoices in the Stendahl Art Galleries Records demonstrate how Stendahl and collaborators imported items into the US. On one invoice dated 7 May 1947, completed at the American Consular Service in Guadalajara, agent Gabriel Sánchez reports 19 baskets containing 236 “Mexican clay idols,” shipped from J. Jesús Zaragoza in Guadalajara to Earl in Los Angeles, imported into the US via El Paso, Texas, by railroad.14 Because the objects were more than one hundred years old, the gallery did not have to pay import taxes. More importantly, the items were legally imported into the US, even though they were not legally exported from Mexico. Echániz also helped Stendahl obtain at least one lot of Maya pieces in 1945, perhaps largely Jaina figurines, given that Stendahl, in a letter from 1946 to American Museum of Natural History curator Gordon Ekholm, boasted of having over 100 examples.15 Once in the United States, these works circulated more easily to other nations.

Other important Mexican sources for the Stendahl Art Galleries, then also involving Earl’s son Alfred (Al), who joined the gallery after returning from World War II, were Raúl Dehesa in Mexico City – the son of Teodoro Dehesa, governor of Veracruz during Díaz’s dictatorship – who sold items that had belonged to the governor; Alberto Márquez in Yucatan, who, as noted by Michael Coe, also had a workshop for forgeries; and the Zaragoza family, who secured works from Jalisco and elsewhere in western Mexico.16 Working channels outside of Echániz and Mexico, the Stendahls also acquired materials from Costa Rica and Panama in the mid-1940s. For Panama, a 1946 document lists eighty “antique Indian curios” for $6516.60 US dollars, shipped from the Canal Zone.17

Meanwhile, the Stendahls were working to cultivate buyers in the US for the thousands of items pouring in. Bliss was a major client of high-priced items, as were the Stendahls’ neighbors Walter and Louise Arensberg, and Nelson Rockefeller, scion of the Standard Oil family and by 1940 a savvy political negotiator between the US and Latin America. Other clients included artists and actors like Charles Laughton, Vincent Price, and Man Ray. The Stendahls also worked with university and municipal museums to add pre-Hispanic art to their collections, among them the Cleveland Museum of Art, de Young Museum, Los Angeles County Museum, Portland Art Museum, Rochester Memorial Art Gallery, Saint Louis Art Museum, Seattle Art Museum, Worcester Art Museum (including through gifts from Aldus C. Higgins), and Yale University Art Gallery (mostly through the gift and purchase of the Fred Olsen Collection). The Stendahls both loaned pieces to those museums for gallery displays and exhibitions, which often led to sales, and established personal relationships with museum directors and curators. In fact, museum directors like Wilhelm Reinhold Valentiner and Thomas Colt, who moved from one museum to another, carried both the Stendahl relationship and the desire to promote pre-Hispanic art to the new museum.

Letters exchanged between Stendahl (and, later, other family members) and museum professionals or collectors convey their conceptualizations of these items and their interest in them. Earl Stendahl, for instance, encouraged museums to acquire pieces from multiple Mesoamerican civilizations. In proposing a selection of items for the Worcester Art Museum, Earl Stendahl wrote to its director, Charles H. Sawyer, “This group would be very educational as it definitely identifies each civilization in such a way that the average layman would quickly learn to recognize the culture.”18 And clients of course expressed their own vision of how to collect or display pre-Hispanic art. Responding to Earl Stendahl, Sawyer emphasized their preference for the aesthetic value of the items: “our Museum collects individual objects of high quality rather than study series which are, of course, of the greatest value to the archaeological museums. It is probable, therefore, that if our Trustees decide to collect in this field, they will be most interested in a few outstanding items of high aesthetic interest.”19

After success in the early 1940s, the Stendahl Art Galleries experienced more challenging times. On the one hand, the Stendahls themselves attributed the slowdown to the competition arising from the 1949 auction of the Brummer Gallery inventory after Joseph Brummer’s death.20 On the other hand, the Stendahls’ investment in what they hoped would be a windfall of Maya material, allegedly “frescoes and figurines” from a cenote in Yucatan, turned out to be forgeries.21 This was a major economic loss for the Stendahls. Earl Stendahl confided to Bliss that he had invested $20,000 (more than $250,000 today) in the “cenote” figurines.22 The Stendahls tried to pass off this “cenote” grouping, as well as a group of “Chumash” objects (allegedly from California) that Echániz sold him, some of which also proved to be fake, on Thomas Gilcrease a few years later, when Earl knew well about the forgeries–at least the Maya ones.23 What became the Gilcrease Institute in 1955 also decided not to buy the so-called cenote objects, as well as on some other dubious materials. This was the second time that Echániz had sold them a corpus of fakes, the first being the aforementioned Zapotec urns. As Al wrote to Earl in 1949, “The whole goddamned business has got me as low as I could possibly get but I suppose experience is the best teacher although quite expensive. Business all over is at a standstill and all are crying. However, I am far from discouraged because we have enough good leads that should mean money but will take a lot of work.”24

Indeed, there were many good leads that Stendahl family members developed. Joseph (Joe) Dammann, Earl’s son-in-law, joined the family business in the 1950s, and letters exchanged among family members show that Joe spent a lot of time looking for pieces in Mexico, traveling to Tijuana, Guadalajara, and elsewhere, but Earl and Al sought inventory too. And they knew how to drum up business: Al wrote to Dr. Otto Karl Bach of the Denver Art Museum on 22 March 1954, “Earl and I just returned from a very successful trip in Mexico and Central America and hit a fine jackpot of Mayan material plus exciting Mexican things.”25

The Stendahls visited Mexico regularly to meet with Echániz or other dealers and at one point in the late 1950s considered renting an apartment in Mexico City with dealer Robert Stolper to help gain inventory, and to have better access to runners and their goods, aided also by Frederick Peterson.26 The Stendahls decided against an apartment, but they continued to work in Mexico. Ramon Folch has shown the work that Peterson achieved in Mexico, creating a vast, unpublished document of private collections in Mexico City, surely of value to the Mexican government a few years later when they were developing the National Museum of Anthropology that would open in 1964.27

In southern Central America, the Stendahls were focusing primarily on Costa Rica and Panama, where there were still options for legal exportation of antiquities. In 1953, they purchased the collection of Jorge A. Lines, comprising fifty-one crates, for $15,000. In the hopes of helping Lines obtain an export permit, which had to be sanctioned by the National Museum, Earl contributed $500 US dollars to that museum.28 The Stendahls succeeded in exporting them and mounted an exhibition of that collection at Scripps College in Claremont, California, in 1953 and exhibited pieces in other exhibitions, including their European tour in the late 1950s.29 They sold multiple items from the Lines collection in 1971 to Frederick Mayer that are now in the Denver Art Museum.30 Nelson Rockefeller bought others that are now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.31 The Stendahls also participated in so-called “digs” in Panama in the early 1950s, in which the family members would take a shovel, yielding pieces for sale.32 One letter by Earl indicates the extent of his travels: “This time I will fly direct to Guatemala ... then to Costa Rica, then to Bogota and Cali then finnish up at Panama wich flys planes direct to N.Y. Have to see Conte again as I think he has some things from his land.”33 This letter refers to the Conte family of Sitio Conte fame, where the Peabody Museum and the University of Pennsylvania Museum excavated.34

After 1950, the Stendahls also mounted many exhibitions themselves across the US, for example in Pasadena, California; Dallas and San Antonio, Texas; Chicago, Illinois; and beyond. Although of course these exhibitions were structured to generate the kind of interest that would subsequently generate business, these exhibitions encouraged the consideration of this material as “art” or even home decoration – as opposed to “artifact” – and exposed other parts of the US to pre-Hispanic cultures and to the idea that their materials could be appreciated for their aesthetics, without the burden of culturally specific or archaeological knowledge. From their first forays into the business, they dismissed the archaeological establishment, but they also were able to speak with authority about contexts archaeologists often did not know: for example, Earl Stendahl wrote sharply to Ekholm to explain Jaina figurines, a category of small-scale ceramic figurines, portraying men and women performing mundane activities, not well known in 1946.35

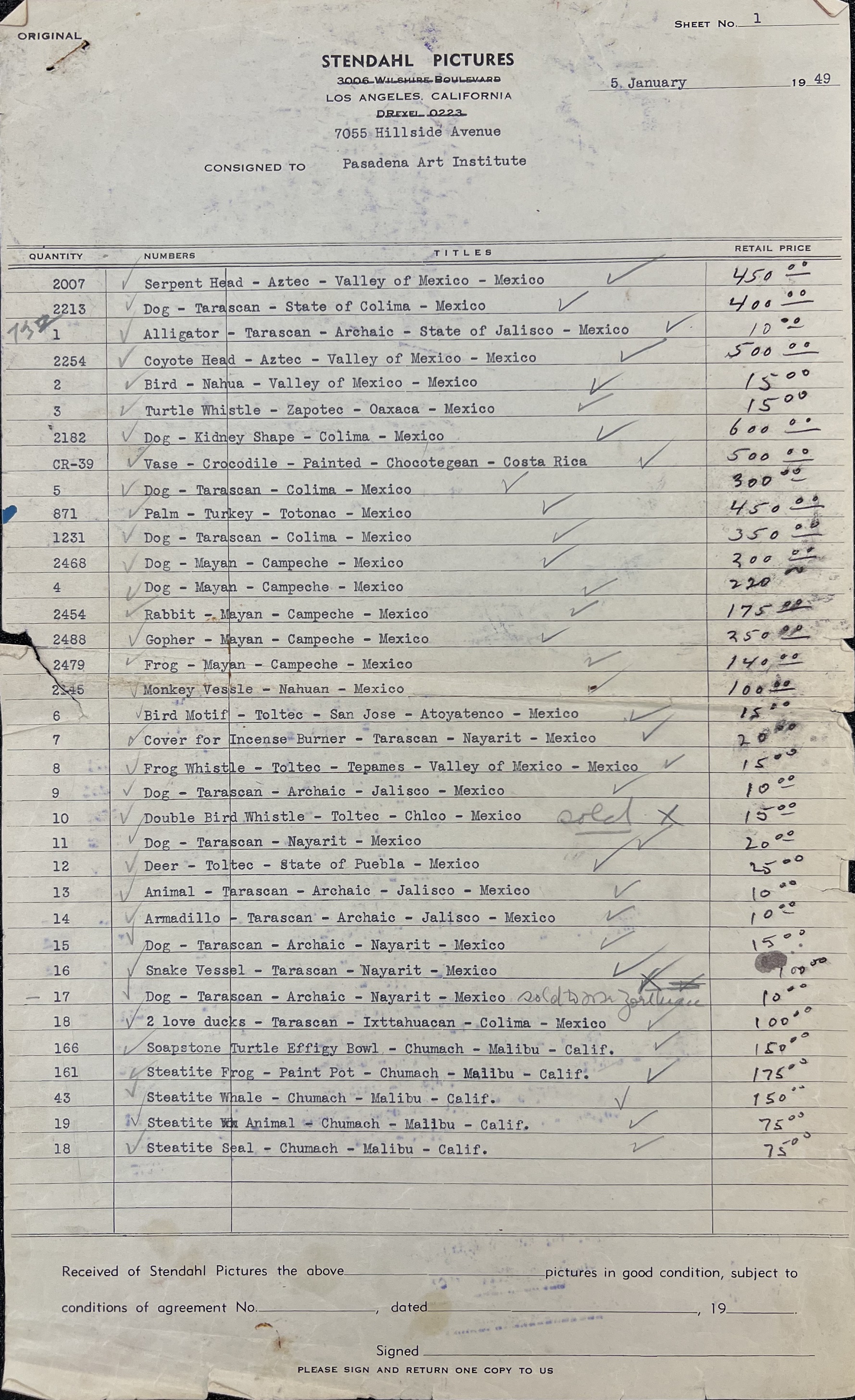

Although the Stendahl Art Galleries presented their exhibitions as educational, with formats of displays and catalogs emulating those of established museums, they were intended to generate business, either by cultivating new clients or by selling items from the shows. In 1943, for example, when the Stendahl Art Galleries exhibited at the Rochester Museum, and in 1943 and 1949 at the Pasadena Art Institute, many works were on consignment, and some were sold during the show. (Fig. 3) This is a practice that they later expanded, but some museums questioned the practice of selling during exhibitions. In a letter addressed to Al dated 13 April 1956, James B. Byrnes, the Associate Director of the North Carolina Museum of Art, conveyed enthusiasm for a Stendahl exhibition but concern over the exhibition’s optics: Valentiner, then director of the North Carolina Museum of Art, who knew the Stendahls from his previous roles at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural history and the Detroit Institute of Arts, “expressed the hope that an exhibition would not ...be construed as a ‘dealer’s event.’” “I trust that it is your intention to de-emphasize the sales gallery aspect,” he wrote.36 Likely for those reasons, North Carolina did not participate. But others did. For instance, the Arts Club of Chicago received ten percent commission on sales from a 1957 show, and what is now the Nelson-Atkins Museum sponsored a Collectors’ Market in 1957, with pieces provided by the Stendahls and other dealers, as a museum fundraiser.

Fig. 3: Stendahl Art Galleries’ consigned works, with retail prices, for Pasadena Art Institute, 1949, box 6, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

Earl did not shy away from stating the source of the objects. When the Stendahls mounted an exhibition at the Dayton Art Institute in 1957, one interviewer in Dayton News asked Earl, “‘What do you call your profession?’” His answer: “‘Why, we’re grave robbers,’ he said frankly. ‘That’s our job. We find these graves in Yucatan, Mexico, Honduras, or wherever the spirit moves us and what we find in the way of these remarkably preserved art treasures are ours.’”37 The Dayton exhibition was a rehearsal for the show that would tour Europe a few years later.

In the meantime, the Stendahls were cultivating buyers in New York City and the Northeast US. They continued to build relationships with some of the same collectors Earl worked with in the 1940s (including Bliss and Rockefeller), but they also developed new ones, such as Fred Olsen and Jan Mitchell, alongside other dealers, including Stolper and Nasli Heeramaneck in both LA and NYC, and New York City gallerists Julius Carlebach, Mrs. Eleanor Ward, and Frances Pratt. The Stendahls also consigned pieces to New York galleries, several of which mounted exhibitions of Stendahl inventory. For instance, the Sidney Janis Gallery, known for Surrealism, exhibited several dozen Stendahl “Tarascan” pieces (from West Mexico) in 1952. And the Widdifield Gallery exhibited first Central American jade and gold and later Maya ceramics and stone sculptures from the Stendahls in 1957.38

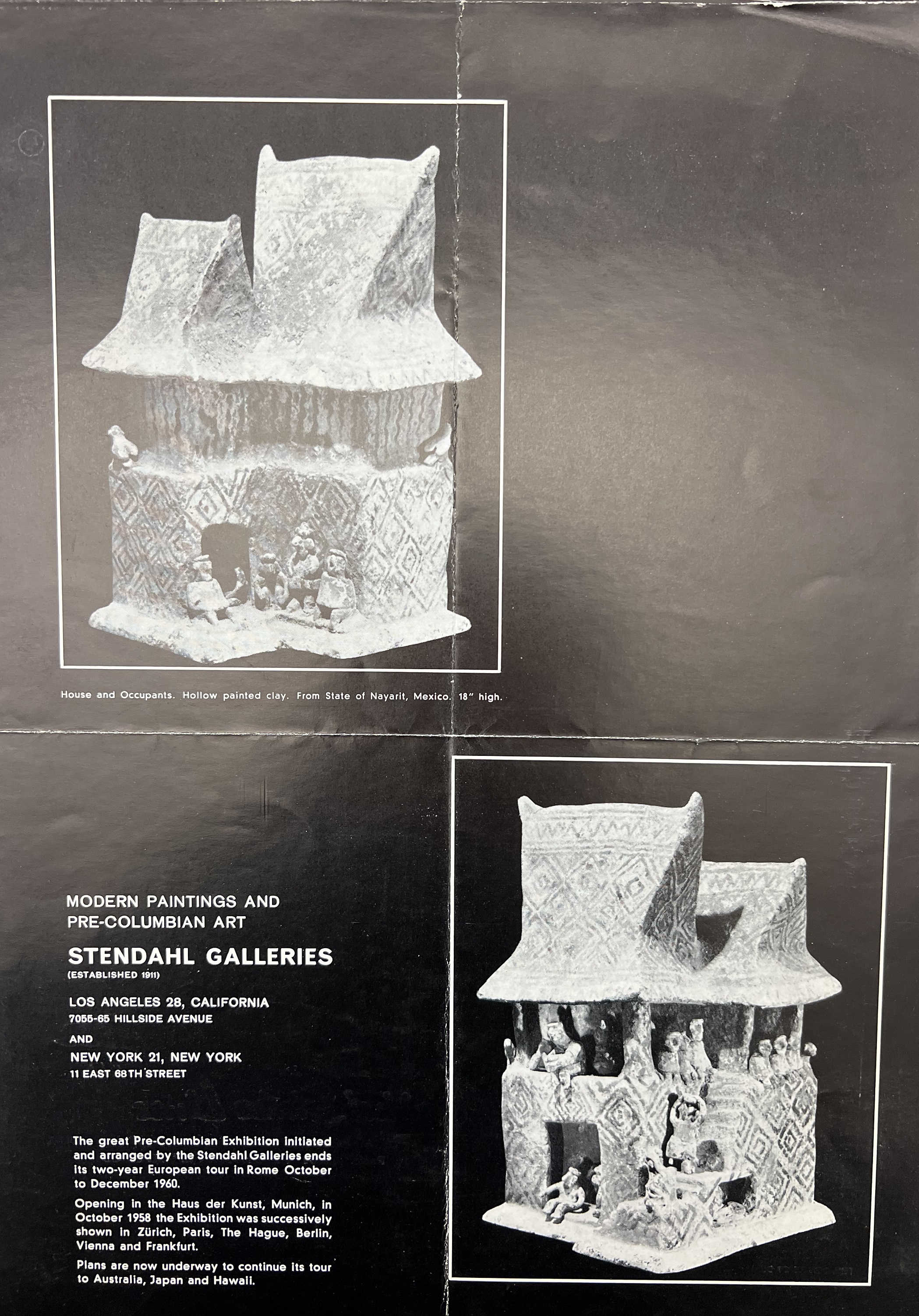

Fig. 4: Stendahl Art Galleries advertisement, 1959 or 1960, box 118, folder 4, SAG, GRI.

The Stendahls also established an outpost in New York City, at 11 East 68th Street, although it wasn’t always an official gallery. (Fig. 4) They handled this expansion by splitting duties of family members. As Al suggested to Earl, “With our organization we should have one in Mex. one in L.A. and one in N.Y. We have to get the stuff and also be able to move it at the same time.”39 Al continued: “We have N.Y. - L.A. and Mexico to take care of. You are in N.Y. so why not stay a while ...what we will need for the future is new customers. If you are meeting people then they should be cultivated. Joe can hit Mexico for two weeks end of month. When he gets back I can let two weeks pass by and hit it again as this is digging time up until summer. Joe and Eleanor [Dammann] can have their turn in N.Y. in spring.”40

They also tried to manage their inventory to meet their expanding market. Perhaps because they came from Hollywood, a mass-market town, they desired to reach the maximum number of clients. They thus also offered many inexpensive items, in order to draw in clients with much less money (than Bliss, for example), who might buy a less expensive ceramic figurine for $10 US dollars. They wrote to each other about what to sell to New York clients and what to save for the European tour that they were planning. As Al wrote, “Sales have been good so far and it might be that we should hold off pushing the good things and concentrate on the secondary material. So much depends on whether or not Europe works out.”41

Europe, a promising market for them, was the big next play for the Stendahls. As Al wrote, speaking on behalf of himself and his brother-in-law Joe Damman regarding themselves and their father, who worked together on the business, “We feel that the actions of the three of us will be governed by whether or not you arrange a European show. If the show goes on then you will probably not want to offer our top pieces and there is no use for anyone to be in N.Y. without top pieces.”42 They also strategized about what to save for the lower end of the market and for department store sales. Few shoppers or exhibition visitors would have wanted to hear what Al wrote in anticipation, “We could put on a sale we have talked about and try to clear the junk out of the basement.... If we could unload our basement in Europe this would be a great thing.”43

The Stendahls’ European tour of “Pre-Columbian Art in Mexico and Central America” did happen, traveling to eight European cities from 1958 to 1960, opening in Munich. 1958 was a year that took the art world by storm, based on the success of Expo ’58 (the first major world’s fair after the War) and the dazzling display of masterpieces exhibited in national pavilions including that of Mexico. Following on the heels of Expo ‘58, the Stendahl exhibition stretched beyond Mexico, encompassing Central America and its goldwork, accompanied by illustrated catalogs and mounted at major institutions like the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna, these exhibitions promoted Stendahl Galleries sales–and those of other galleries too. (Fig. 5)

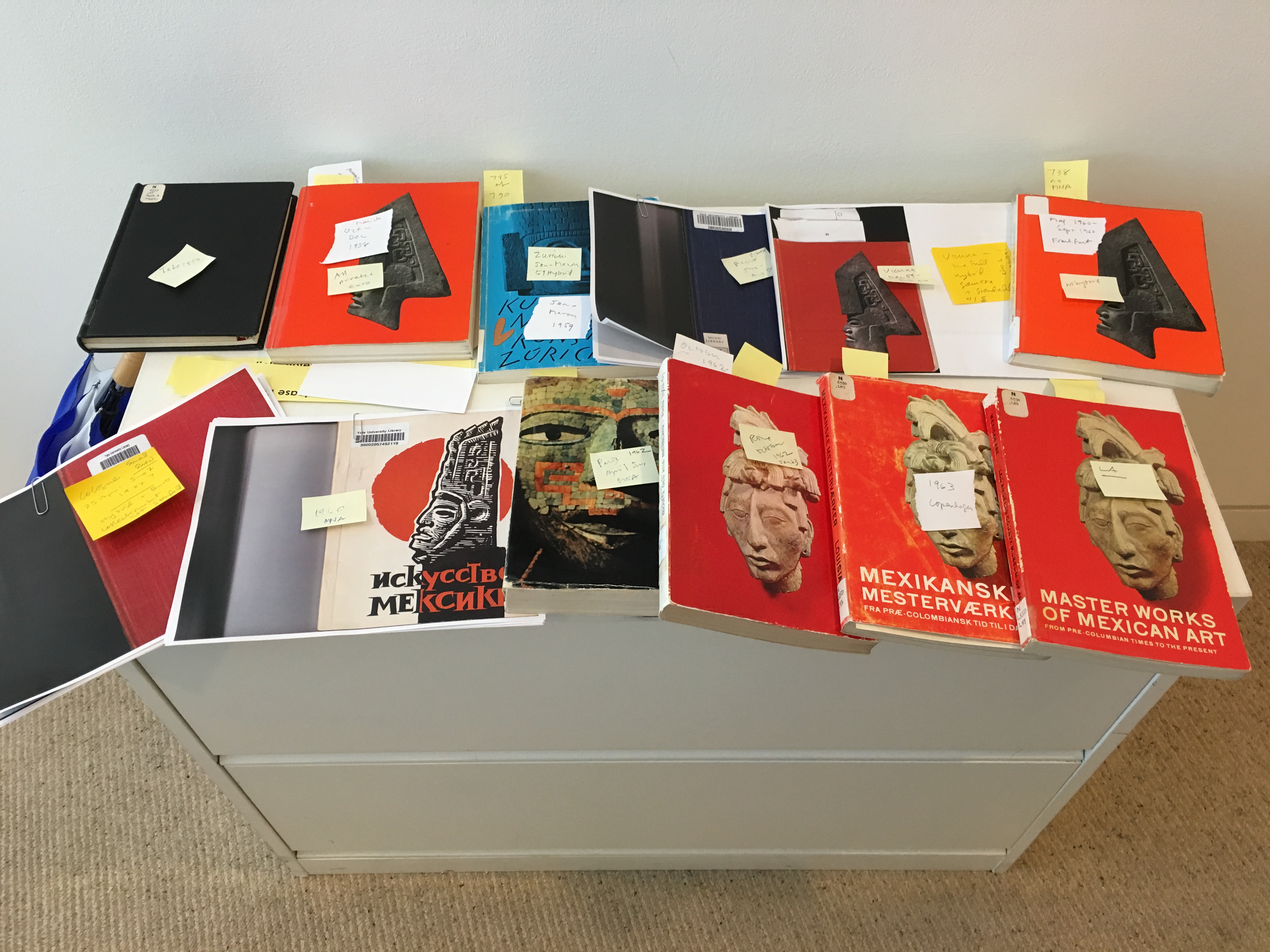

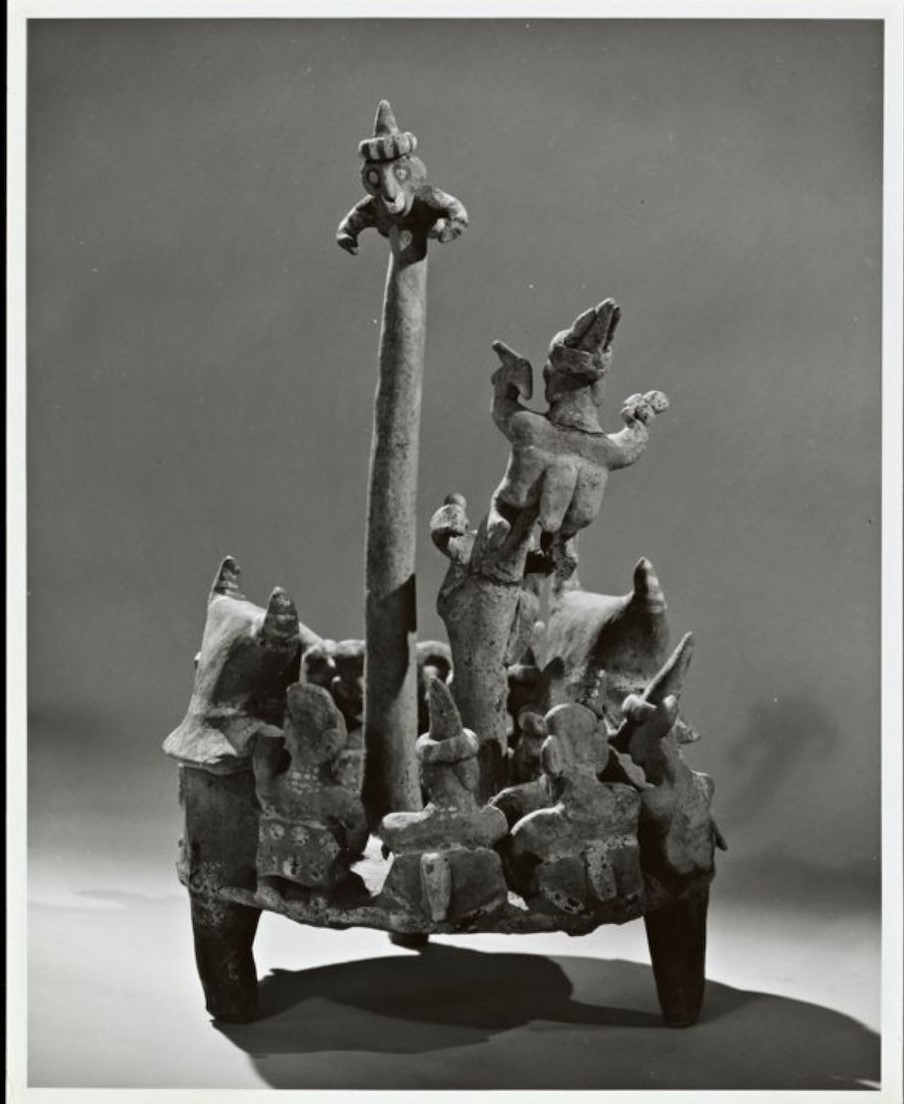

The Stendahl catalog was a polished production, featuring a sleek red cover with an image of a palma – no text, except on the spine. (Fig. 6) They also commissioned modernist photographer Julius Shulman to photograph the objects, with carefully staged lighting that Shulman used to create dramatic tonal contrasts and prominent shadows (Figure 7). The result is a seamlessness, for which the Shulman photos and modernist cover create an essential whole. The catalog also presented excellent academic bonafides, with texts written by Samuel K. Lothrop (Harvard archaeologist and adviser to Bliss, thus involved in both scientific archaeology and the art market44), and German scholar Gerdt Kutscher.

Fig. 5: Exhibition catalogues for Stendahl Art Galleries exhibition tour and Mexican national collection exhibition tour. Photo: Mary Miller.

The European museums paid a flat fee for the show and covered some Stendahl family expenses. Those museums made money by charging for tickets and selling catalogs, activities that continue to be standard ways for museums to raise funds.45 Objects were also sold during the exhibition, for which the museums received 10% commissions. Peter Ade, the Director at Munich’s Haus der Kunst, received 5% commission, since he helped organize the tour.46 In addition to inventory from the Stendahls, private clients and US and Canadian museums – from Bliss and Olsen to the Portland (Oregon) Art Museum and the Royal Ontario Museum – lent objects to the tour.

The touring show featured nearly eight hundred pre-Hispanic objects, and no doubt the stars were the changing constellation of works borrowed from European museums, including the famous “Headdress” held by the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna.47 Those famous works undoubtedly brought in more visitors, but the Stendahls wanted their contributions to be clear. As Earl wrote, “We separated our material from the Loan material and are using three large rooms. The Museum in Rome sent some wonderfull mosaic pieces and the Basel Museum in Switzerland sent some fine stone pieces. Also some great things from Berlin and wonderful stuff from Vienna.”48 Likely because of a concern of being connected to an art dealer, some museums tried to limit the display of Stendahl pieces, to the Stendahls’ chagrin. Regarding the Zürich venue, Earl wrote, “The Kunsthaus people ... will leave out much of our material including the stone piece we sold. ... I will insist that the Stendahl material will be held intact and not mixed up with the other loan material. If any are used in the loan section it will have to have our card on it. ... I am going to up prices on some things and ‘no sale’ on others.”49

Fig. 6: Stendahl Art Galleries Munich catalogue, Präkolumbische Kunst aus Mexiko und Mittelamerika, Haus der Kunst, Munich, 1958.

There were conflicts regarding sales, just as there had been in North Carolina. Marlborough Fine Art Ltd. was initially enthusiastic about participating in a London show: As H.R. Fischer wrote in April 1961, “As far as I can see from your sale prices, I hope it will mean quite an interesting business for us.”50 But three months later, Marlborough withdrew, because the British Museum would not support the sales: “I have seen three important clients during the weekend, all famous collectors of antiquities. They all have told me that they have stopped buying Pre-Columbian art as the British Museum is not prepared to give them any tests.” This referred to scientific analyses to determine authenticity. Thus, he continued, “It seems to me that I cannot sell any Pre-Columbian objects without the help of the British Museum’s advice and therefore I do not see any possibility of holding such an exhibition.”51 A letter the next week gave more information: “Mr. Adrian Digby, Keeper of the Department of Pre-Columbian Art at the British Museum, refuses to give any expert advice on pieces of Pre-Columbian Art. The reasons for this are a) there are whole organisations who make fakes and b) all pieces in circulation have been taken out of Mexico illegally.”52

Fig. 7: “Pole Ceremony,” Nayarit, Mexico. Photograph by Julius Shulman for Stendahl Art Galleries, 1958, for European tour. Source: Alfred Stendahl, Pre-Columbian Objects, 2557-26, GRI, 2004.R.10.

But the show was already on the road, and there were sales from other venues: both museums and collectors bought pieces that the Stendahls made available as they traveled along with the exhibitions – including during one 10-month stretch for Earl in 1958-1959. Although Al later recounted in a1977 interview that this was not a “sales exhibition,” “at the end of the show some of the things were left, stayed in Europe...it did create a lot of interest, which resulted in us doing a little bit of business there.”53

There also are many family letters regarding dinners or meetings with potential clients and sellers of European and other art. These contacts paid off during the tour and years later. For instance, Earl met privately with Mr. Josef Müller (who would build the core of the Barbier-Müller collection), who bought from him during this tour, as did his niece, Mrs. Edith Hafter. These works continue to be monetized in the present day. One Teotihuacan sculpture, sold to Hafter by Stendahl, was sold again at auction in 2013.54

Earl also met often with Elsy Leuzinger, Director of the Rietberg Museum in Zürich, who purchased works in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In a 1958 letter regarding Leuzinger, Earl recounted: “She came down to Munich for two days to select the things she would like to have her board buy. Some $28,000.00 to $35,000.00 worth of stuff. Payment over two years if board O.K.’s it.”55 This communication coincides with a letter and an invoice dated 28 January 1958 listing items that the Rietberg Museum purchased from the Stendahls; these were from Costa Rica, Mexico, and Peru and totaled $11,070 – which would be more than $115,000 in today’s dollars.56 Of items from Stendahl now at the Rietberg three were illustrated in the European exhibition catalogs (including the Zürich one), and two of those were from the aforementioned Lines collection.57 The Stendahls’ business dealings also continued after the tour. In 1962, they sold the Rietberg a Maya stela, which was shipped by Swiss Air from New York to Zürich.58 The museum also made significant purchases from Stolper, including a Maya stone panel in 1963 that is likely from Pomoná, Tabasco, Mexico.59

As their shows rolled along, the Stendahls also sold to dealers across Europe and established steady clients. Franco Monti, a Milan dealer, became a major client, as noted in the Stendahl stock book recording multiple purchases. One letter from 1964, only two years before Earl’s death, but after the European tour had wrapped, gives a sense of their continuing relationship, and of Earl’s unbridled energy: “Spent 30 minutes with Monti at airport in Milano between planes. Gave him [a] photo of Maya bowl, net price $3,000.00 Also left him 5 objects on consignment for a total of 22,000.00 net to me.”60 Although they had sold to some European collectors before the exhibition, the exhibitions and attendant schmoozing expanded the Stendahls’ network of European dealers, museums, and collectors broadly from 1958 onward and for at least a decade. But the Stendahls were not selling only pre-Hispanic art. In these years they continued to sell modern European art and bought and sold pieces from Syria, Egypt, Iran, Turkey, and elsewhere: in May 1962, while in London, Earl reported that he sold $16,000 US dollars of Near Eastern material.61 The Stendahls also acquired and sold European paintings of significance. For example, on 30 June 1959, Earl wrote to Al about Degas, Vlaminck, and Renoir paintings they were trying to sell for top dollar.62

The Stendahl exhibitions coincided with the Mexican exhibition organized for the Mexican Pavilion at Expo ‘58 in Belgium, and curated by museographer Fernando Gamboa, art touring in advance of new national museums dedicated to anthropology, colonial art, and modern in 1964.63 Gamboa, one of the founders of Mexico’s National Institute of Fine Arts in 1947, followed the framework of the 1940 MoMA show to mount several exhibitions featuring Mexican art from pre-Hispanic times to the present. Masterworks of Mexican Art toured in European cities and in Los Angeles from 1959 to 1964.64 The pre-Hispanic section featured objects from Mexican national collections but included a few works from Mexican private collections, many of which were absorbed into the national collections.

But in three venues – Vienna, Zürich, and Berlin – the shows merged: the objects of Mexico’s Expo ‘58 pavilion joined ones from the Stendahl show.65 The two series of shows displayed collections that were in some ways so different from each other – Mexican national patrimony versus explicit commodities – yet both displayed objects from private collections. In other ways they were complementary: one treated all of Mexico and Central America before the European invasion, and the other extended into the twentieth century. Inside the shared catalog were pieces from the two shows, at times juxtaposed; on one spread, the Aztec Teocalli of Sacred War from Mexico’s national collection, faces a Stendahl piece, acquired from Echániz and smuggled out of Mexico. (Fig. 8)

This was a troubled merger. The objects credited “Stendahl Galleries, Hollywood” in the earlier catalogs are indicated only by “S.” in the catalogs of the joint exhibition. The Mexican government did not want to give the Stendahl Art Galleries equal footing: after all, there had been articles published in Mexican newspapers since 1944 decrying the looting and smuggling of the Tetitla mural from Teotihuacan (which Stendahl sold to Bliss), although the Stendahl and Bliss names were not always spelled out.66 In a 1977 interview, Al shed light on the catalogs of the shared show: “They didn‘t want Stendahl Galleries staring them in the face.”67

The family letters also reveal enmity behind the scenes. In one letter from 1958, Earl reported that he had been told that “Gamboa was in [Munich] and was greatly impressed and made the crack that Stendahl had too many fine things.”68 Earl’s wife Enid Stendahl also reported, regarding the Zürich venue: “When we arrived from Basle Thursday eve, there was an urgent note .. to contact Kunsthaus at once...Mexico had been screaming there was to be no mention of Stendahl... nor was he to be at a dinner being given for the Ambassador from Mexico. ... Slightly ironical – seeing it was originally our show!”69 And as Earl added on 30 June 1959, “The Mexican bunch will not speak to us and shure have been putting the knife in our backs. They have practically taken over the show and I am looking for trouble in a big way. We can not go to Mexico for a long time. You better write Joe [Dammann] to get in and out quick.”70 It is no surprise that the two shows split and went their separate ways.

Fig. 8: Double-page spread from Vienna catalogue: Kunst der Mexikaner, Kunsthaus Zürich, 1959, pp.90-91.

The Stendahl exhibition made final solo stops in Frankfurt and Rome in 1960, and the Stendahl name was restored in those catalogs. Gamboa launched a grander vision than before: hundreds of works of Mexican art, from earliest days until mid-twentieth century, traveled to Moscow, Leningrad, and Warsaw in 1960-61, and then in a yet larger configuration in Paris, Rome, and Humlebæk, Denmark, in 1962-63. This final exhibition was the show that traveled to Los Angeles, where the 1963-64 exhibition was an important binational event, and Mexico’s former President Miguel Alemán attended opening events alongside Stendahl clients. Afterwards, the pre-Hispanic works from the show were installed in the splendid new anthropology museum in Mexico City in 1964. Meanwhile, the Stendahl Art Galleries launched Pre-Columbian Art, a touring exhibition that began at the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles in 1963. Both the Stendahl and Mexican exhibitions may have increased the desire for collecting ancient Mexican art yet again, especially because they were displayed in the same city at the same time. The Stendahl exhibition continued to travel, showing elsewhere in California, and in Arizona, Texas, and Colorado until 1965. It was intended, as the gallery claimed in the catalog, “to celebrate the 30th anniversary of our first Pre-Columbian art exhibition.”71 That presumably was one in the gallery at 3006 Wilshire Boulevard in 1935. Three decades later, they had expanded far beyond that space, completing a multi-state tour, on the heels of a multi-national exhibition.

Earl was home in Hollywood when the Mexican show opened in Los Angeles in October 1963. He had folded his tent in New York just as other major pre-Hispanic dealers took over the market there: André Emmerich, Alphonse Jax, Ed Merrin, Frances Pratt, Walter Randall, and others. But he continued selling to the client base forged while in Europe. Circa 1940, he had been a key figure in shifting the market in ancient Mexican art from Europe to the US, but by mid-century, he tapped into European wealth and interest in art, just as notions of what belonged in an art museum were changing. And Ratton, who arguably was responsible for Earl’s entering the pre-Hispanic art market (via Matisse), eventually became Earl’s friend and client.72

Although the road caught up with Earl in 1966, when he died suddenly at seventy-eight while in Morocco, the world he had set in motion was seemingly unstoppable, and pre-Hispanic art was everywhere, in exhibitions, in popular culture, in advertisements, and for sale in US department stores, and looting to seek new goods had increased.73 A huge department store sale of pre-Hispanic art took place in 1966, the same year as Earl’s death, at the May Company in Los Angeles, located next to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) on Wilshire Boulevard. Filled with items that Morton May had purchased from the Stendahl Art Galleries, the sale followed the Stendahl model of offering both high-priced items and inexpensive pieces in bulk, artworks within reach for display in both wealthy museums and middle-class homes. Looted Maya stone sculptures were among those offered for sale there and in other venues in 1966: Naranjo Stela 8 was put up for sale in the May Company department store, the Stendahl Art Galleries sold Piedras Negras Stela 2 to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, and newly looted stone sculptures from El Cayo, Lacanja, La Corona, and Piedras Negras were advertised for sale in the Parisian Galerie Jeanne Bucher’s Sculpture Maya, prepared with the help of Mexican art advisor José Luis Franco.74 And Alfred Stendahl and Joe Dammann continued the work of the Stendahl Art Galleries, at times in collaboration with dealers like Jax, Everett Rassiga, and Stolper, which allowed them to seek larger prizes like those stone sculptures or finely carved Olmec jades. Al soon would complete the next family project, the 1968 tome with Hasso Von Winning that memorialized the Stendahl Art Galleries’ decades of dealing pre-Hispanic art (with Von Winning’s name on the cover).75 The preference for Maya and Olmec art pointed to in the 1968 Von Winning volume, in distinction to the West Mexican that had been the volume business for the Stendahls, would lead the way in taste for the rest of the century.

But no one in the family was ready for what would happen next: on the heels of the opening of the new Mexican National Museum of Anthropology in 1964, new agreements, including the 1972 Treaty of Cooperation between the United States of America and the United Mexican States Providing for the Recovery and Return of Stolen Archaeological, Historical and Cultural Properties and the 1972 Mexican Federal Law on Archaeological, Artistic, and Historic Monuments and Areas, would begin to make the smuggling of items out of Mexico – business that had long been illegal in Mexico – illegal in the United States and beyond as well. But the market would continue, and the Stendahls – and other dealers – would shift to other regions yet again, as museums across the US and in Europe continued to buy and develop their collections to display pre-Hispanic materials as art.

Megan E. O’Neil is Assistant Professor at Emory University. Mary E. Miller directs the Getty Research Institute.

1 We are grateful to the Getty Research Institute (GRI), its pre-Hispanic Art Provenance Initiative (PHAPI), and specifically to Dulcinea Cano, Andra Darlington, Alicia Houtrouw, Theresa Marino, Sally McKay, Kit Messick, Payton Phillips Quintanilla, Arnold Toral, Andrew Turner, and the Zooniverse transcribers. We also are appreciative of Ron and April Dammann for donating the archives to the GRI and for many conversations about their family’s history. Thanks also to Martin Berger (Leiden University), Ramon Folch (Arizona State University), Serge LeMaitre (Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Belgium), Victoria Lyall and Lori Iliff (Denver Art Museum), Phil MacLeod (Emory University), Matthew H. Robb (Library of Congress), and Esther Tisa-Francini and Fernanda Ugalde (Museum Rietberg).

2 These letters are part of the Stendahl Art Galleries Records, which consist of business documents, correspondence, and photographs that were donated to the GRI by Ron and April Dammann in 2017 (GRI, 2017.M.38). PHAPI was established in 2019 to study these records in relation to the larger market for pre-Hispanic art in the twentieth century. The spelling in these letters is not always standard, but we refrain from inserting “[sic]” at each occasion, to reduce repetition.

3 April Dammann, Exhibitionist: Earl Stendahl, Art Dealer as Impresario (Santa Monica: Angel City, 2011), 13.

4 Consignment lists sent by Charles Ratton to Pierre Matisse, undated (before 1936), Pierre Matisse Gallery Archives, MA 5020, Gift of the Pierre Matisse Foundation, 1997, Morgan Library and Museum; Megan E. O’Neil, The Changing Geographies of the Mesoamerican Antiquities Market circa 1940: Pierre Matisse and Earl Stendahl, in Andrew D. Turner and Megan E. O’Neil, ed., Collecting Mesoamerican Art before 1940 (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, forthcoming, 2024).

5 Ellen Hoobler, Smoothing the Path for Rough Stones: The Changing Role of Pre-Columbian Art in the Arensberg Collection, in Hollywood Arensberg: Avant-Garde Collecting in Midcentury L.A. (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2020), 354.

6 Earl Stendahl (hereafter ELS) to Diego Rivera, March 27, 1936, Stendahl Art Galleries Records, 1907-1971, Smithsonian Archives of American Art (hereafter, SAG, AAA).

7 O’Neil, Changing Geographies; Payton Phillips Quintanilla, Megan O’Neil, Matthew Robb, and Mary Miller, Stendahl Galleries Records: Guillermo Echániz Correspondence, GRI LibGuide (2022). https://getty.libguides.com/Stendahl.

8 Nierendorf’s collection is largely at the Guggenheim Museum today. No extensive papers survive, although the first picture on the Guggenheim website shows him with a pre-Hispanic Colima dog. https://www.guggenheim.org/history/karl-nierendorf

9 Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, in collaboration with the Mexican Government, 1940); Megan E. O’Neil and Mary Ellen Miller, ‘An Artistic Discovery of America’: Mexican Antiquities in Los Angeles, 1940–1960s, in Wendy Kaplan, ed., Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915–1985, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: LACMA; DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2017), 162–67.

10 Karl Nierendorf to ELS, 12 October 1940; ELS to Karl Nierendorf, 16 October 1940. Stendahl Art Galleries Records, 1907-1971, Series 4, SAG, AAA.

11 See, for example, André Emmerich (hereafter AE) to Arnold Maremont, 19 October 1967, citing Ekholm as authority, and Alan Schwartz to AE, 30 November 1964, citing Bird as authority. In May and June 1968, Emmerich disputed a challenge of authenticity from Lord Victor Rothschild regarding a gold necklace, noting that the “American Museum of Natural History also confirmed authenticity prior to sale.” All: André Emmerich Records and André Emmerich Papers, Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, c 1929-2009, Box 10.

12 Mary Ellen Miller, Megan E. O’Neil, and Matthew Robb, The Teotihuacan Proposition: or, How a Wall Painting Became a Painting on a Wall, in Megan E. O’Neil and Andrew Turner, ed., Promoting Pre-Hispanic Art, 1940–1968: Museums and Collections in the United States and Mexico (Los Angeles, GRI, forthcoming); Phillips Quintanilla et al., Guillermo Echániz Correspondence.

13 Miller, O’Neil, and Robb, Teotihuacan; Phillips Quintanilla et al., Guillermo Echániz Correspondence.

14 Consular Invoice of Merchandise, 7 May 1949, box 91, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

15 ELS to Gordon Ekholm, 26 June 1946, Department of Anthropology, AMNH, 1940-50.

16 Michael D. Coe, From Huaquero to Connoisseur: The Early Market in Pre-Columbian Art, in Elizabeth H. Boone, ed., Collecting the Pre-Columbian Past (Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, 1990), 271-290. For lists and consular invoices of various dates, box 91, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

17 Consular Invoice of Merchandise, 25 January 1946, box 91 folder 1, SAG, GRI.

18 ELS to Charles H. Sawyer (hereafter, CHS), 24 November 1941, box 9, folder 4, SAG, GRI.

19 CHS to ELS, 13 January 1942, box 9, folder 4, SAG, GRI.

20 Unnamed (likely Alfred E. Stendahl [hereafter AES]) to ELS, 19 May 1949, box 106, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

21 AES to A. Llamas, 14 May 1949, box 14, folder 23, SAG, GRI.

22 ELS to RWB, 24 November 1948, box 10a, folder 4, SAG, GRI.

23 List of offered objects, Stendahl Art Galleries to Thomas Gilcrease, undated (1949 or later), box 11, SAG, GRI. Regarding Chumash: Georgia Lee, Fake Effigies from the Southern California Coast? Robert Heizer and the Effigy Controversy, in Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 15/2 (1993), 195-215.

24 Unnamed (likely AES) to ELS, 20 May 1949, box 106, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

25 AES to Otto Karl Bach, 22 March 1954, box 2, SAG, GRI.

26 AES to ELS, undated (possibly 1957), box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

27 Ramon Folch, personal communication.

28 Jorge A. Lines (hereafter, JAL) to ELS, 5 May 1952, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; ELS to JAL, 3 June 1952, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; JAL to ELS, 30 July 1952, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; JAL to Joseph Dammann (hereafter JWD), 3 December 1952, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; JWD to JAL, 14 January 1953, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; JAL to AES, 31 July 1953, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI; AES to JAL, 19 June 1953, box 12, folder 3, SAG, GRI.

29 Ancient Art from Costa Rica. Scripps College, Oct. 20-Nov. 12, 1953, exh. cat. (Claremont, CA: Scripps College, 1953), n.p.

30 Unnamed (possibly AES or JWD) to Frederick R. Mayer, 28 May 1971, box 15, folder 17, SAG, GRI. These include Stendahl C-737 (DAM 2017.245), C-751 (DAM 1993.755), C-776 (1993.753), C-795 (DAM 1995.453), C-806 (DAM 1995.728), C-975 (DAM 2017.241), C-978 (DAM 1993.570), C-979 (DAM 1993.569), C-992 (DAM 1993.976), C-2055 (DAM 1993.754), C-2140 (DAM 1993.985), C-2151 (DAM 2017.243), C-2160 (DAM 1993.568), C-2165 (DAM 1993.567), C-2134 (DAM 2017.248), C-2252 (1993.570), C-2254 (1993.756), C-2542 (DAM 1995.495), and C-2715 (DAM 1993.760). C-737 is illustrated in the Stendahls’ Ancient Art from Costa Rica exhibition catalog of 1953.

31 Met Museum 1979.206.378a,b, 1979.206.379, and 1979.206.426.

32 ELS to William M. Milliken, 25 January 1952, box 1, folder 10, SAG, GRI.

33 ELS to Stendahl family, Thursday 21 October unnamed year, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

34 Samuel Kirkland Lothrop, Coclé: An Archaeological Study of Central Panama, Part I: Historical Background, Excavations at the Sitio Conte, Artifacts and Ornaments (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, 1937).

35 ELS to Gordon Ekholm, 26 June 1946, Department of Anthropology, AMNH, 1940-50.

36 James B. Byrnes to Al Stendahl, 13 April 1956, box 4, folder 2, SAG, GRI.

37 Si Burick, Interview with “Grave-Robber”--They Had Ball Games Eons Ago. Dayton Daily News, 27 October 1957, v.81, no. 91, p. 14, box 2, folder 1, SAG, GRI.

38 Martin Widdifield Gallery, The Pre-Columbian Jade and Gold Exhibition, April 23-May 17, 1957, exh. cat. (New York: Martin Widdifield Gallery, 1957); Martin Widdifield Gallery. Art of the Maya civilization–Exhibition, September 4 to October 5, 1957, exh. cat. (New York: Martin Widdifield Gallery, 1957).

39 AES to unnamed (likely ELS), undated, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

40 AES to ELS, undated (possibly 1957), box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

41 AES to ELS, undated (possibly 1957), box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

42 AES to Earl and Enid Stendahl, undated, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

43 Unnamed (likely AES) to ELS, undated, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

44 For example, Samuel Kirkland Lothrop, Metals from the Cenote of Sacrifice, Chichen Itza, Yucatan (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, 1952).

45 ELS to AES, 3 March 1959, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

46 ELS to AES and JWD), 30 January 1959, box 105, folder 7, SAG, GRI.

47 Präkolumbische Kunst aus Mexiko und Mittelamerika und Kunst der Mexikaner aus späterer Zeit (Vienna: Künstlerhaus, 1959), 60.

48 ELS to Enid Stendahl and family, undated, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

49 ELS to JWD, undated, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

50 H.R. Fischer to AES, 24 April 1961 box 4, folder 5, SAG, GRI.

51 H.R. Fischer to JWD, 12 July 1961, box 4, folder 5, SAG, GRI.

52 H.R. Fischer to AES, 19 July 1961, box 4, folder 5, SAG, GRI.

53 Alfred Stendahl and George Goodwin, Alfred Stendahl: Oral History Transcript (Los Angeles: UCLA Library, 1976), 70.

54 “Teotihuacan Stone Figural Censer,” Koller & Galerie Walu, vente 19. Geneva Sale 11 December, 2013 African & Oceanic Art, Precolumbian Art Collection Alberto Galaverni and other private collections.

55 ELS to Enid Stendahl and family, undated, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

56 Elsy Leuzinger to ELS, 28 January 1959, box 6, folder 10, SAG, GRI; ELS to Elsy Leuzinger, Invoice, 28 January 1959, box 6, folder 10, SAG, GRI; Ancient Art from Costa Rica, n.p.; Kunst der Mexikaner, exh. cat. (Zürich: Kunsthaus, 1959). The Museum Rietberg object numbers are the following: RMA (Rietberg Meso-Amerika) 18, 302, 17, 304, 505, 303, 506 (Lines collection), 112, 113, 507 (Zürich exhibition catalog Plate 74, Cat. #497; Lines collection).

57 Ancient Art from Costa Rica, n.p.; Kunst der Mexikaner. RMA 408 and 505 were published in the Zürich catalog (Plate 73, Cat. #479 and Plate 75, Cat. # 509, respectively).

58 Swiss Air, Air Waybill, for 1 crate, artwork (stone Maya stela), consigned to Rietberg Museum by Stendahl Galleries, 6 May 1962, box 6, folder 10, SAG, GRI. The Museum Rietberg object number is RMA 307.

59 Christian M. Prager and Antje Grothe, The History of a Maya Relief: The tension between transfer of cultural property and knowledge production, in Esther Tisa Francini, ed. Pathways of art: How objects get to the museum, exh. cat. (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2022), 387-406.

60 JWD to AES, 21 April 1964, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

61 ELS to JWD, 24 May 1962, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

62 ELS to AES, 30 June 1959, box 105, folder 7, SAG, GRI.

63 O’Neil and Miller, Artistic Discovery; Ramírez Vázquez, The National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico: Art, Architecture, Archaeology, Anthropology (New York: Abrams, 1968).

64 Carlos Molina, Fernando Gamboa y su particular versión de México, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, núm. 87, 2005, 117-143.

65 O’Neil and Miller, Artistic Discovery.

66 César Lizardi Ramos, Escándolo por el Robo de una Gran Pintura India: Obra Teotihuacana del Siglo VII, Substraída y Vendida al Extranjero. Excelsior, 27 Nov 1944, 6. Mexico City.

67 Stendahl and Goodwin, Alfred Stendahl: Oral History Transcript, 69–70.

68 ELS to JWD, undated, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI.

69 ELS to JWD, 18 March 1959, box 105, folder 6, SAG, GRI.

70 ELS to AES and JWD, 30 January 1959, box 105, folder 7, SAG, GRI.

71 Stendahl Art Gallery, Pre-Columbian Art (California: Otis Art Institute, 1963).

72 “Mother” (presumably Enid Stendahl”) to “Every One” (Stendahl family), Saturday 19 September, unnamed year, box 105, folder 8, SAG, GRI; Eleanor Stendahl Dammann to “All” (Stendahl family), 7 April 1964, box 106, folder 1, SAG, GRI. Ratton died in 1986: https://www.metmuseum.org/research-centers/leonard-a-lauder-research-center/research-resources/modern-art-index-project/ratton

73 Matthew H. Robb, The Pre-Columbian as MacGuffin in Mid-Century Los Angeles, in Jesse Lerner and Rubén Ortiz-Torres, ed., LA Collects LA (Los Angeles: Vincent Price Art Museum, 2017), 49–59.

74 Galerie Jeanne Bucher, Sculpture Maya (Paris: Editions Jeanne Bucher, 1966); Matthew H. Robb, Daniel Aquino Lara, and Juan Carlos Meléndez Mollinedo, La Estela 8 de Naranjo, Petén: Medio siglo en el exilio, in Bárbara Arroyo, Luis Méndez Salinas, and Gloria Ajú Álvarez, ed., XXIX Simposio de Investigaciones Arqueológicas en Guatemala, 2015 (Guatemala: Museo Nacional de Arqueología y Etnología, 2016), 629-638; Megan E. O’Neil, Engaging Ancient Maya Sculpture at Piedras Negras Guatemala (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012), 193, 201, 210.

75 Hasso Von Winning, Pre-Columbian art of Mexico and Central America (New York: Abrams, 1968).