ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Waltraud M. Bayer

In the wake of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks embarked on a massive nationalization drive in the sphere of culture. Major art collections once belonging to the court, the nobility, the bourgeoisie, and the church were confiscated and added to the state museum funds. Newly drafted and implemented expropriation and nationalization laws allowed formerly private art property to be then sold abroad. The Soviet art sales of the interwar period were disputed: Russian émigrés sued the Soviet government and its Western partners for illegally profiting from auctioning off their rightful private property. To this date, the sales constitute a complex, politically and legally controversial matter. Long taboo, thorough research made possible by perestroika centered notably on the very institutions that suffered the greatest losses – the Hermitage and the Palace-Museums in and around St. Petersburg, and to a lesser extent Moscow institutions. Post-Soviet museum research has yielded impressive results: Above all, it has produced a series of (mostly uncensored, unabridged) publications of edited archival funds. This relates to Jewish collections seized by the National Socialists, to Soviet émigré collections as well as to collections and museum funds of the former Soviet republics. Contemporary Russia regrets the loss of its national heritage; efforts to repurchase art sold in the interwar period are now financed by Russia’s economic elite.

In the wake of the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks embarked on a massive nationalization drive in the sphere of culture. Art collections once belonging to the court, the nobility, the bourgeoisie, and the church were confiscated and added to the state museum funds. The ‘loot’ was categorized, researched, and then redistributed – to the art institutions established in the tsarist era, to the short-lived ‘Proletarian’ and the newly founded Soviet art museums. The unparalleled confiscations were carried out in the name of the people and of Socialist ideals, in the name of public enlightenment and the creation of a new, proletarian culture. Furthermore, the artworks could be exchanged for hard currency needed to finance the country’s industrialization.

The Kremlin began to sell cultural patrimony abroad – both at public auctions and through middlemen, in some cases in great secrecy. The sales benefitted public museums, libraries, and private collections across the globe. In the 1980s, the long-tabooed Soviet art exports have become a topic of interest in international scholarship and – as a result of litigation in European and American courts – in provenance research. For post-Soviet Russia, the sales – deeply regretted since perestroika – are an emotionally charged, multi-layered issue.

From 1918 to 1938, the Soviet Union exported artworks, antiques, tapestries, furniture, libraries, icons, liturgical objects, and jewelries by the ton. Outside the USSR, the disputed issue caused much publicity: It received wide media coverage, was repeatedly litigated in courts, and the legitimacy of whether to participate in the sales was debated by Western governmental institutions. In a satirical comedy on Bolshevik Russia, even Hollywood dealt with the theme.1 With the outbreak of World War II, however, the sales completely faded from public memory.

In the 1980s, interest was revived by American research, selectively at first.2 With the demise of Communism, the subject reached Eastern Europe. In post-Soviet Russia, the first revelations unleashed strong patrimonial emotions; in particular, the early publications during glasnost aroused wide-spread public outrage and disbelief over the scope and quality of the unprecedented loss.3

Since then, scholars have unearthed a flood of sources and data previously inaccessible – resulting in a steady stream of conference proceedings, archival editions, films, memoir and article publications, which has enriched our understanding greatly. The bulk of the tedious, continuous task lay with the institutions that suffered the greatest losses – primarily with the Hermitage, the Palace-Museums, and the nationalized collections of the high nobility in and around St. Petersburg, and the Kremlin museums in Moscow.4 As for the globally dispersed public and private collections that then acquired the exported art, American museums and libraries took the lead and – unlike their European counterparts – published their records and findings, often in cooperation with their Russian colleagues. Among them are the New York Public Library, the Hillwood Museum, and the National Gallery of Art, both in Washington, D.C.5

Fig. 1: Jan van Eyck, The Annunciation [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. It left the State Hermitage Museum in 1930 to be sold to Andrew W. Mellon who in turn donated it to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. In 1997, the van Eyck returned temporarily to Russia as part of a bilateral Russian-American research and exhibition project.

What emerges from their output is a detailed account of the myriad Soviet bureaucratic systems for confiscating, inventorying, appraising, and selling off imperial Russia’s artistic wealth and material culture. Edited sources document the complex organization and inept handling of the massive exports. They provide a nuanced picture of the legal framework, political context, the global network of the central alliances, and of the multi-phased chronology. They support the assertion that the cultural patrimony exported during the first post-revolutionary decade “caused little serious damage”6 to the country’s major art holdings. Objects selected for sale initially came from antique stores, pawn shops, bank vaults, abandoned residencies, and burned estates (later also from the core museum funds).

Initial marketing policies were loosely coordinated. Sales took place both at home, yielding low returns, and largely abroad. Members of the Communist Party and of the Communist International, trade missions, diplomats, and agents mainly traded in the valuables from Soviet repositories. In 1923, museums (in order to raise their revenues) were entitled to dispose of their property considered second-rate, damaged, unneeded, or duplicates. Beginning in 1924, they could also sell items from the nationalized collections they had received for safekeeping with the revolution; as these seized funds were not recorded in the inventory books, they were – strictly speaking – not part of the state museum funds and thus not protected by law. Apart from a few exceptions, museum funds were exempted from the sales prior to 1926 when systematic requisitions from state museums began.7

Studying the museum sales in the context of the overall museum policy reveals that the peak period (1928-1932) “followed on the heels of an intensive effort to preserve and inventory”8 Russian cultural heritage. The achievements in restorations, historic preservation, and pioneering museum policy of the immediate post-revolutionary period (1918-1924) seem to contradict the liquidation of cultural patrimony. What is worse, and in the words of a leading expert “one of the great ironies”9, that with the creation of the State Museum Reserve a centralized repository was established; art treasures once stored in private locations throughout the country were now easily identifiable, “making their sale more efficient to organize”.10

In 1925 the Central Office for Purchase and Realization of Antique Objects ‘Antikvariat’11 was founded. Rapidly assuming a monopoly, it launched an aggressive strategy in exporting art, antiques, and books. It liquidated the palaces of the nobility (such as the Stroganov, Anichkov, and Elagin) which since nationalization had been operating as museums. Their contents were prepared for sale.12 By 1927, it ordered museums to select objects “of no museum value”13 from their funds. The resulting initial export consisted largely of applied and decorative art, furniture, dinner services, and silverware of imperial and noble households, of goods mainly from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.14 In January 1928, the government (in need of financing its First Five-Year-Plan) issued the decree On Measures to Intensify the Export and Realization of Antiques and Works of Art.15 Antikvariat now demanded larger, more precious quotas.

Assessing the scope of the ensuing deliveries from the museums as well as the extent of the translocations in general is no longer possible. In terms of quantifiable data, so far no final comprehensive estimate exists. Many records, archives, libraries, and funds were destroyed, lost or exiled in World War I, the revolution, the Civil War, and in World War II – both in the USSR, primarily in and around besieged Leningrad, and in the West (as many middlemen and buyers were Jewish). Many works were repurchased, relocated or restituted, and their provenances eradicated, impeding research today. It is, however, widely acknowledged that the repercussions on the Soviet, notably on the St. Petersburg museums, were catastrophic – both in scope and quality.

With perestroika, some institutions have accounted for their loss: Requisitions for export are documented for the Hermitage from February 1928 on.16 By April that year, the museum had already released 1,300,000 rubles worth of works of art – more than its annual budget.17 From March 1928 to October 1933, more than 24,000 items were removed.18 Among them were 2,880 paintings, 350 of which were of special importance and fifty-nine masterpieces, eighteen (of originally forty-eight) Rembrandts, including his best portraits and his only landscape. It is now known that in terms of quality, in particular, the once unique Dutch collection of the Hermitage suffered immeasurable losses; about 300 first-class works of Dutch masters had to be handed over to Antikvariat. Other Hermitage departments sustained significant damage as well: Over 16,000 objects of West European applied art – furniture, porcelain, crystals, textiles, bronze, silver, gold, and precious stones – had to be selected for export, along with hundreds of items of antique gold jewelry and miniatures.19 (Comparable data exist for the Palace-Museums whose quantitative losses surpassed those of the Hermitage).20

Coming to terms with this detrimental sell-off was inconceivable to contemporaries. The government enforced institutional cooperation; it cut state funding for the upkeep of the Hermitage in half, “so that the museum would be obliged to replace it by selling works abroad”. It fought the “opposition and inertia of the museum staff who were conducting a campaign against the export requisitions”.21 In legitimizing rhetoric (“Rembrandts for tractors”), the authorities stressed the relevance of the export for the Soviet industrial buildup. Attempts to protect the museum collections led to demotions, removals, and arrests of museums directors and curators. This is broadly documented, e. g. for the Hermitage, the Kremlin Armory, and the Moscow State Central Workshops; as for the latter, the entire organization was “purged and their staff arrested”.22 Finally, in 1929, Anatolii Lunacharskii resigned as head of the People’s Commissariat for Enlightenment (in charge of museum issues), after being censured by the party for his solidarity with the museum experts.23

Resistance to the sales was ultimately crushed and censored by the regime. In the wake of this crackdown, the specialists previously in charge of selecting and appraising were subordinated to untrained Communist functionaries and so-called “shock-brigades”; quotas and time limits were dictated, decisions on which objects to discard for export were taken in haste, at the peak within thirty seconds.24 Motivated by the need for hard currency, priority was given to create outlets abroad. The Kremlin launched a media campaign to promote the cultural exports: Envoys were dispatched to institutions in the West to screen their capacity for Russian art.25 Exhibitions were mounted to acquaint the foreign clientele with the artistic legacy from the USSR ahead of the sales.26 International experts and potential customers were invited to Moscow and Leningrad to prepare for the venture together with their Soviet partners. The former were granted access to the country’s museums, vaults and repositories to pre-select merchandise.27 Auction catalogues were published in foreign languages containing detailed provenances and information on the works and artists.

Diplomatic recognition of the USSR by the countries involved in the ‘Russian auctions’ was a central concern. All Soviet legislation pertaining to the confiscation, the nationalization and the multiple use of art works formerly in private hands had to be acknowledged by Moscow’s respective partners.

Starting in October 1917, in an attempt to systematically dismantle the structure of private ownership, the Bolsheviks passed a series of decrees (later to be supplemented and amended). An evolving comprehensive legislation consequently regulated the expropriation of the court, the Imperial family, the nobility, the bourgeoisie, the Orthodox Church and other religious groups, professional organizations, institutions, and associations. The right of inheritance was abolished, and the ownership of art, books, and valuables severely restricted. Controls were placed on private collections: Works of artistic and historical importance had to be inventoried and registered, permits were required for exports. Private holdings of private value could remain in place if ‘protection certificates’ were issued. The nationalization, registration, and export laws provided a solid legal framework (which later proved) to withstand protests and litigation in Western courts. Thus, as far as the Soviet government was concerned, all artistic wealth was exported legally.28

In contrast, outside the USSR the issue of legality was disputed. The sell-off met with public protests, opposition, growing concern on the part of the Kremlin’s foreign partners, and litigation – both by émigrés who had lost their property and, later by their heirs. With the accelerated sale through European auction houses from 1928 on, Moscow found itself repeatedly in court. In November 1928, the two thousandth jubilee auction at Rudolph Lepke’s, Berlin, prompted widely publicized legal actions: More than sixty émigrés claimed ownership of works offered, sued for the return of their property, briefly succeeded in a temporary halt of a portion of the auction items. Finally, upon political pressure from Moscow, they lost their suit on the grounds that the nationalization had been a lawful act by a government that Germany had recognized.29 Only days later, a Berlin-based Russian émigré claimed the confiscation of his art works from the ‘Russian auction’ held in Vienna.30

In the spring of 1929 Princess Olga Paley (Palei), widow of Grand Duke Paul shot by the Bolsheviks, initiated court action against a London dealer to prevent the sale of her art collection and the interior of her palace in St. Petersburg.31 The Court of Appeal of England and Wales (COA) rejected the suit. As the British government recognized the USSR de jure in 1924, English courts could not inquire into the legality of the acts of a foreign government when such action takes place within the territory of the foreign state. The COA stated that the contract of sale described the former Paley possessions as “nationalized property” and thus “by the law of Russia the goods claimed were the property of the Russian government”. The court’s ruling further acknowledged Soviet legislation pertaining to the State Museum Fund and the requisition of émigré property; even in cases when the seizure of former private property “began without legal justification, or only by revolutionary right ... it was ultimately adopted by a government ... recognized by the British government as the lawful government of the territory in which the property was”. Dismissing Paley’s appeal, the judge concluded “and I can find nothing in the Russian decrees enabling their former owner to complain in these or any courts of the sale by the Russian government”.32

With Moscow prevailing in the Paley landmark case, the ensuing lawsuits brought against Russian auctions in Europe and in the USA were equally unsuccessful.33

The attitude of the international community towards the sales, which had been wary and ambiguous even prior to émigré litigation, remained vigilant. When Paris-based Russian émigrés loudly protested the Berlin auctions in late 1928, the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided not to acquire any art and antiques of Soviet provenance as long as private property remained an unresolved issue.34 Officially, the Quai d’Orsay called for absolute neutrality with respect to France’s diplomatic recognition of the USSR; government officials and the Louvre staff were not allowed to participate in public actions. Unofficially, the art exports were condemned.

Fig. 2: Raphael , The Alba Madonna [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. The most expensive single work of the Soviet art sales at over US$1,7 million, the picture was bought by Andrew W. Mellon and is today in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C.

As the sales continued, French museum directors lost some of their reserve and addressed inquiries to the authorities. This is documented on various occasions, as in the spring of 1931 when curators at the Louvre learned of French drawings from the Hermitage being auctioned off in Germany. Simultaneously, when the landmark auction of the Count Stroganov collection was announced for Berlin, a portrait by Lebrun was among the lots. Again, the Louvre appealed to the Foreign Ministry to be finally permitted to bid in the auctions, at least through agents and for works “with clearly identified provenances”35; the ministry declined. The Lebrun deal fell through, but many others did not. As archival research confirms, French institutions in the end benefitted from the sales.36 They acquired art and antiques of French provenance from Russian collections, but also Russian art – often through middlemen, “mysterious donors” or agents abroad.37 The Louvre’s purchases are still little known, as is generally the case with most European private and public collections.38

As of 1929, the economic crisis and the imminent threat of lawsuits – despite the rulings an attendant embarrassment – impacted on the sales. Soviet authorities became “more cautious than they previously had been”39 about what they publicly sold abroad. They turned to more secrecy, offering patrimonial culture in covert or semi-official deals through agents to private collectors in the USA and in Europe. Irreplaceable Old Masters left the country, among them paintings and sculptures by Botticelli, Raphael, Titian, Veronese, Tiepolo, Velázquez, Poussin, Watteau, Lancret, Chardin, Robert, Houdon, Terborch, van Eyck, van Dyck, Bouts, Hals, Rubens, Rembrandt, Cranach, or Burgkmair. Some of the main beneficiaries later donated their purchases to public institutions in the West: The French-Armenian oil tycoon Calouste S. Gulbenkian gave his collection to the city of Lisbon. Andrew W. Mellon, then U.S. treasury secretary, endowed his Soviet acquisitions to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., which he founded. Diplomats who had access to nationalized art and antiques – while on service in the USSR – acquired large holdings they eventually made public. Joseph E. Davies, U.S. ambassador in Moscow, bequeathed his collection to the museum of the National Cathedral. His wife Marjorie Merriweather Post (formerly Davies) founded the Hillwood Museum (both in Washington, D.C.).40

In addition to the “private transactions”, the overt sales in Europe proceeded. With the economic crisis worsening, the selling slowed and prices fell, increasingly plummeting; from mid-1929, many items could not be sold abroad at all, not at the prices fixed by the Soviets, and were later returned to the USSR. In 1933, when the Nazis closed the Soviet trade mission in Berlin, the USSR was deprived of its sales headquarters in Europe. Exportation continued, but was increasingly curtailed by the Kremlin, first in late 1933 (when the requisitions from the core museums funds were halted), again in 1936 (with the closure of the state-run Torgsin-stores that also traded in valuables); in 1938, it came to a final close when the Soviet government reinstated the ban on the export of art and antiques.41

With the millennium the archival reconstruction of the mass exports had yielded widely published results, and Russian politics could no longer ignore the factual and emotional dimension of the sales. A consensus gradually emerged in post-Soviet Russia to at least partially make up for the losses museums suffered in the interwar period. Repatriating cultural patrimony was of primary concern – both to the new political and economic elites. Together they have started to engage in tracing and repurchasing some of the treasures, and in some cases in the restitution of works to those state institutions that had custody of these items immediately before their sale.42 Museums, sponsors, and the Ministry of Cultural Affairs have cooperated on this issue, raising it to national importance.

The most active enterprise in this field is the Link of Times, the foundation established by the Moscow-based oil tycoon Viktor Vekselberg (Veksel’berg). In 2004 it became known to an international public when it bought about two-hundred objects made by the St. Petersburg court jeweller Peter Carl Fabergé (1846-1920). Vekselberg purchased the entire collection of New York publishing magnate Malcolm Forbes from Sotheby’s in the run-up to an auction cancelled on short notice. These rare items once graced the finest collections of tsarist Russia. Most of them belonged to the tsar’s family. The federal government welcomed the fact that precious items, once nationalized and sold for a nickel under Lenin and Stalin, were again in Russian hands. The Ministry of Cultural Affairs helped the foundation bring the valuable commodity, said to have been sold for $100 million, into the country tax free. It went on display at the Kremlin and later in several other museums at home and abroad. Since 2015, the collection – by then enlarged to c. 4,000 items – has been on permanent display in the Shuvalov Palace in St. Petersburg.43

The 2004 purchase marks the first climax of a concerted effort to compensate for the interwar translocations. Repatriating items of cultural significance so far primarily pertains to imperial and church provenances. Thus, in 2007, upon request from the Russian-Orthodox Church, the Link of Times finalised negotiations to repatriate (and later restitute) eighteen church bells from Harvard University to St. Danilov Monastery, Moscow.44 In 2013, Vekselberg (and others) helped mediate a solution following years of litigation over the restitution of Jewish cultural property in the USA; the settlement resulted in the return of the Schneerson Library to the Moscow Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre. The original American claim to hand it over to the legitimate heir, a Brooklyn organization, was not upheld.45

In many ways, the Link of Times (despite its formal non-governmental foundation status) is exemplary and indicative of contemporary Russian cultural and memory politics. Official post-Soviet Russia deeply regrets the immense, irreplaceable patrimonial loss and supports its repatriation: It applies symbolic amends and deals with the sensitive issue on a case-by-case-basis; on occasion, it practices selective, partial restitution. The latter pertains mainly to the Russian-Orthodox Church (ROC), which got back some of its property seized after 1917. Apart from the growing concessions to the ROC, a concerted approach to the issue of revolutionary dispossession is avoided. The general policy of expropriation is still considered to be legitimate. Restitution to the nationalized treasures’ former owners – primarily representatives of the Romanov dynasty, the nobility, and the bourgeoisie – is not recognized. Several heirs have initiated legal proceedings for recovery from abroad. Their claims were ultimately rejected on the ground that litigation was not feasible under foreign jurisdiction. A well-documented case is that of the Shchukin family who since 1993 had tried to reclaim their art collection – in France, Italy, and the USA, to no avail. In follow-up suits, requests for just compensation for the confiscated property or for at least proportionate payments of the material benefits accrued to the Russian Federation (through loan exhibitions and reproduction rights) were equally dismissed.46

With rising international litigation over Communist expropriation of cultural objects, new forms of binding agreements, known as Immunity from Seizure, were introduced. These bilateral guarantees protect cultural objects on temporary loan from the Russian Federation against any form of seizure during the loan period abroad.47 In 2008, President Dmitrii Medvedev installed a commission to investigate the legitimacy of the art exports.48 Under his successor, Russia’s faltering democracy impacted on the cultural sphere: By 2013 Putin (who previously had not commented on the legality issue) publicly opposed restitution of art patrimony confiscated by the Soviet government. Referring to Russia’s painful legacy in the twentieth century and its severe ruptures which triggered off multidimensional patrimonial translocations, he pleaded not to open the Pandora’s Box.49

The plea reflects the current fundamental discourse over Russian identity narratives that – among other measures – led to the adoption of the State Cultural Policy Foundations in late 2014. This first official cultural canon (since 1992) was passed in a rather neutral version after months of fierce debate. According to United Russia, the ruling party, its main goal lies in the task to reconcile Russian society, to honor and promote its historic traditions, and to create a unified cultural space within its borders.50

On the centenary of the revolution, reconciliation assumes high priority, as Russia is restoring continuity with its past that its Bolshevik predecessors broke off. In an attempt to bridge the gap between the tsarist and Soviet imperial traditions, a selective approach to its blurred past is pursued. By declaring national history a matter of national security, Russia seems to be in a state of forgetfulness of its own revolutionary origins, in a process of negation.51 Against this background, the need to arrive at a final, transparent assessment of the interwar art sales is no longer felt. Institutional silence is preferred at home.

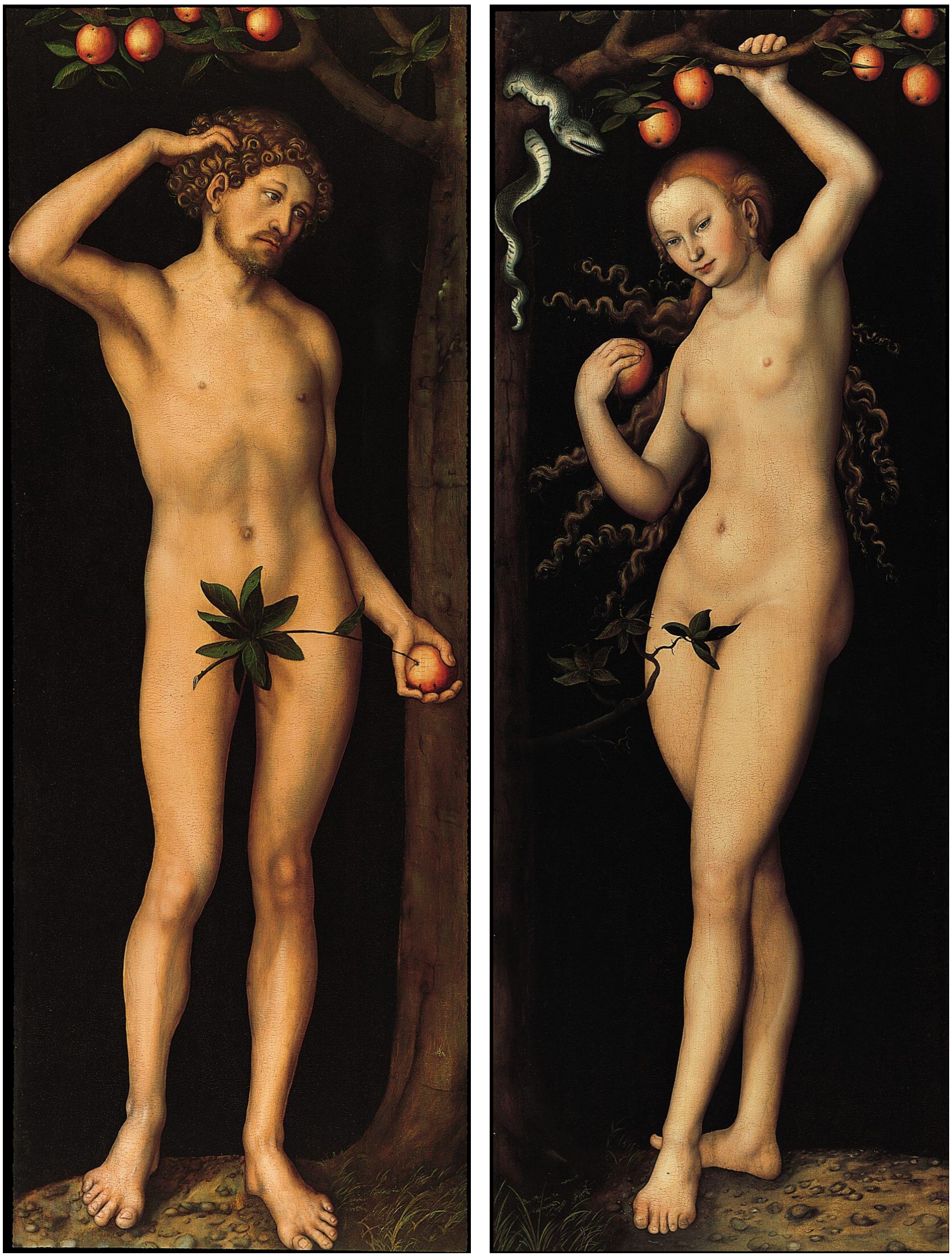

Fig. 3: Lucas Cranach the Elder, Adam and Eve [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Abroad, the art market takes its toll, as in the Holocaust-related claim on the return of two Cranach panels, Adam and Eve (fig. 3). In 1931, they had been acquired by the Amsterdam dealer Jacques Goudstikker (1897-1940) from the Berlin auction of the Stroganov collection. During World War II, Goudstikker had to flee occupied Holland; both his private and firm holdings were seized by Hermann Göring. After the war, these assets were secured by allied forces and restituted to the government in The Hague which in turn distributed them to Dutch museums; among the art returned were Adam and Eve. Later, however, they were reclaimed by George Stroganov-Shcherbatov, a Russian noble émigré. He sold the works to the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. With the Washington agreement of 1998 to return seized Jewish property to the original owners or their heirs, Goudstikker’s family sued the Dutch government successfully: The assets were restituted, albeit without the Cranach. The claimants, who learned of the Dutch deal with the Stroganov heir only later, initiated litigation anew – against the Norton Simon Museum, demanding the return of the panels on the ground that the Soviet nationalization of private property (and thus the interwar acquisitions) had been lawful. The California courts turned down the case – explaining that the expropriation laws of foreign states could not be dealt with in the USA.52

The battle over Adam and Eve exemplifies that the issue of the Soviet museum sales is connected to “a past that won’t pass”53 (Henri Rousso) mainly in connection with forced translocations that are globally condemned. Contrary to the European research on Holocaust-era assets and ‘trophy art’ with its political backing and consequently with its major funding programs, the topic still has no political lobby and is “virtually unnoticed outside a small scholarly community”.54

Waltraud M. Bayer, Priv.-Doz., is a Vienna-based historian specializing in East European museum studies from 1850 to the present. She has published widely, notably on Russian and (post-) Soviet collections, public and private art institutions, and the art market.

1 The movie ‘Ninotchka’, directed by Ernst Lubitsch, released in 1939, starred Great Garbo as special Soviet envoy dispatched to Paris to close the sale of nationalized jewelry formerly belonging to the Russian nobility and halted by French court action. Contrary to the interwar rulings, the fictitious princess dispossessed and exiled by the revolution won the suit in the film.

2 On the ground-breaking research see Robert C. Williams, Russian Art and American Money, 1900-1940 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1980). Williams had to focus on the American buyers, as under Brezhnev the issue of the art sales pertaining to the Soviet sellers was off limits.

3 Among the first Russian publications was Aleksandr Mosiakin, “Prodazha”, in Ogonek, 6 (1989), 18-22.

4 As the article addresses a transnational, cross-disciplinary audience, the numerous publications available in Russian are not listed here. For further reading, specialists are referred to two volumes which contain the results of Russian archival studies in English or German translation: Waltraud Bayer, ed., Verkaufte Kultur: Die sowjetischen Kunst- und Antiquitätenexporte, 1919-1938 (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2001); Anne Odom and Wendy R. Salmond, eds., Treasures into Tractors: The Selling of Russia’s Cultural Heritage, 1918-1938 (Washington, D.C.: Hillwood Museum and Garden, 2009).

5 The American buyers are generally well researched. See, for example, the respective chapters of the various institutions in: Odom / Salmond, Treasures. On the first joint exhibition see the bilingual catalogue: Jan van Eyck: The Annunciation (National Gallery of Arts, Washington, D.C. / State Hermitage, St. Petersburg, 1997).

6 Anne Odom and Wendy R. Salmond, From Preservation to the Export of Russia’s Cultural Patrimony, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 3-31, here 16.

7 Ibid., 14. Elena Solomakha, The Hermitage, Gosmuzeifond, and Antikvariat, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 111-135, here 115.

8 Anne Odom and Wendy R. Salmond, Preface, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, xiv.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid., xiv-xv.

11 Set up within the People’s Commissariat for Commerce, this institution was reorganized and renamed repeatedly until approx. 1937 when it was closed down.

12 Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 17.

13 Solomakha, Hermitage, 115.

14 Ibid., 116.

15 Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 17.

16 Solomakha, Hermitage, 117.

17 The annual Hermitage budget then amounted to 1,150,000 rubles. Ibid., 118.

18 Ibid., 112.

19 Elena Solomacha, Verkäufe aus der Eremitage, 1926-1933, in Bayer, Verkaufte Kultur, 41-62, here 56-58.

20 From October 1928 to October 1929, Antikvariat appraised a total of 5,453,622 items from the Leningrad Palace-Museums, the State Museum Reserve as well as from Moscow and Ukrainian institutions: Rifat Gafifullin, Sales of Works from the Leningrad Palace Museums, 1926-1934, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 137-165, here 159.

21 Solomakha, Hermitage, 117.

22 Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 19.

23 Ibid. In the wake of the Cultural Revolution (1928-1931), a new generation of radical Marxist custodians criticized Lunacharskii’s policy to preserve, restore, and display the nationalized patrimony of the ‘class-enemy’ and to recruit museum personnel among the former elites; to them, the task of the new museums was not to ‘protect the past’ and to maintain ‘bourgeois object-fetishism’, but to transform art institutions into propagandistic vehicles. On the repercussions of the Cultural Revolution on the sales see Konstantin Akinsha and Adam Jolles, On the Third Front: The Soviet Museum and Its Public during the Cultural Revolution, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 167-181.

24 Solomacha, Verkäufe, 51.

25 Waltraud Bayer, Revolutionäre Beute: Von der Enteignung zum Verkauf, in Idem, Verkaufte Kultur, 19-40, here 26; also Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 17.

26 The sales exhibits were organized at home and abroad. In the USSR, they were held in the nationalized palaces to lend the objects selected for sale “a special cachet” and “to tempt foreign dealers”: Ibid., 17. On the shows to market icons abroad: Waltraud Bayer, Erste Verkaufsoffensive: Exporte nach Deutschland und Österreich, in Idem, Verkaufte Kultur, 101-131, here 120-122.

27 On the special access of German dealers to Soviet repositories: Ibid., 102.

28 Bayer, Revolutionäre Beute, 23; Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 6-7.

29 Anja Heuss, Stalins Auktionen in Berlin, in Sediment. Mitteilungen zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels, 2 (1997), 85-94.

30 Bayer, Erste Verkaufsoffensive, 113.

31 Princess Paley Olga v. Weisz and Others, English Court of Appeal (on appeal from the King’s Bench Division of the High Court of Justice), 21 March, 1929, is frequently cited in legal arguments regarding the right of individuals to reclaim property seized by their country of origin. It is available as download under the abbreviated form: Princess Paley Olga v. Weisz [1929] 1 KB, 718.

32 All quotes from ibid.

33 On further litigation see, for instance: Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 18.

34 Francine-Dominique Liechtenhan, Verdeckte Geschäfte mit Frankreich, in Bayer, Verkaufte Kultur, 133-150, here 135-136.

35 Ibid., 141.

36 Ibid., 141-143. Having drawn on archival material in the Louvre and the French Foreign Ministry, Liechtenhan documented that French museums mainly acquired French art (Fragonard, Saint-Aubin), sculptures, and furniture from Soviet funds (e. g. furniture from Trianon Palace, Versailles, sold to tsarist Russia with the French revolution). Chantilly, for instance, acquired the album of the Comte du Nord, the later Tsar Paul I, had commissioned in 1784; it comprised colored views of this palace near Paris.

37 Ibid., 142.

38 On the Louvre’s request to purchase Russian icons: Ibid. On the Dutch-Soviet art trade see Janine Jager, Reger Handel mit den Niederlanden, in Bayer, Verkaufte Kultur, 151-170.

39 Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 18.

40 Olof Aschberg donated his celebrated icon collection to the National Museum of Fine Arts, Stockholm: http://www.nationalmuseum.se/sv/English-startpage/Collections/Painting/Icons/. On the acquisitions by the couple Davies-Post see, for instance, Anne Odom, American Collectors of Russian Decorative Art, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 265-295; Wendy R. Salmond, Russian Icons and American Money, 1928-1938, in Odom / Salmond, Treasures, 237-263.

41 Odom / Salmond, From Preservation, 26.

42 On the repatriation of imperial items from the reigns of Peter I. and Elizabeth I. for the Hermitage see Boris Stanishev, Kak my sami u sebja vorovali shedevry, in Argumenty i fakty (June 22, 1999), 14.

43 The foundation has acquired Russian fine and applied art from Russian and European noble collections: http://fabergemuseum.ru/en/about/link_of_times. The palace, on lease from the city government, had been nationalized in 1918: http://fabergemuseum.ru/.

44 The bronze bells, totaling 26 tons, had been bought by the American businessman and diplomat Charles R. Crane in 1929 and donated to Harvard University in 1930. Link of Times financed the repatriation deal: http://www.danilovbells.com/bells/.

45 Vekselberg is on the JM-board of trustees: https://www.jewish-museum.ru/en/libraries/schneerson-library/.

46 The Shchukin case was resolved diplomatically prior to an exhibit at Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris, in 2016. On the Shchukin and Konovalov follow-up suits see Jane Graham, “From Russia” Without Love: Can the Shchukin Heirs Recover Their Ancestor’s Art Collection?, https://www.law.du.edu/documents/sports-and-entertainment-law-journal/issues/06/From-Russia-Without-Love.pdf.

47 Nout van Woudenberg, State Immunity and Cultural Objects on Loan (Leiden: Brill, 2012).

48 Prodazhi iz Ermitazha byli nezakonnymi?, in Art Khronika 1 (2009), 24.

49 Putin protiv vozvrata tsennostei, konfiskovannykh posle revoliucii, https://ria.ru/culture/20130219/923722946.html.

50 On the State Cultural Policy Foundations see Waltraud M. Bayer, Moscow Contemporary. Museen zeitgenössischer Kunst im postsowjetischen Russland (Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2016), 52-63.

51 James Ryan, The Politics of National History: Russia and the Centenary of Revolutions, 2ß January 2017, http://www.cultures-of-history.uni-jena.de/politics/russia/the-politics-of-national-history-russia-and-the-centenary-of-revolutions/.

52 Anja Heuß, Russisches Kulturgut in (westeuropäischen) jüdischen Sammlungen: Von den Berliner „Russenauktionen“ bis zur „Arisierung“, in Bayer, Verkaufte Kultur, 204-213. On Goudstikker: Jager, Reger Handel, 163-166. Leila Amineddoleh, The Norton Simon Museum’s Multi-Million-Dollar Nazi Restitution Case of Two Paintings by Cranach the Elder, Explained, 4 April 2016, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-the-norton-simon-museum-s-multi-million-dollar-nazi-restitution-case-explained.

53 Cristelle Terroni, The Recovered Memory of Stolen Works of Art (Interview with Prof. Bénédicte Savoy), Feb. 22, 2016, http://www.booksandideas.net/The-Recovered-Memory-of-Stolen-Works-of-Art.html.

54 Odom / Salmond, Preface, xiii.