ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Christine Howald / Léa Saint-Raymond

During the Second Opium War (1856-1860), British and French troops fought to expand their privileges in China. The war ended in Beijing in October 1860 with the looting and burning of the Yuanmingyuan, one of the official seats of government of the Chinese Emperor to the northwest of the Chinese capital. Thousands of these objects – figures up to over a million have been suggested – were brought to Europe and are today in Western museums and private collections. Little is known about the quantity of objects that reached Europe, about the market mechanisms in the West, the collectors that purchased the artefacts from the Summer Palace, as well as the paths taken by the objects in the years after 1860: which objects arrived in Europe? In whose hands were they at what time? When did they change hands? Where are they today? While it is difficult to trace the marketing of the artefacts sold through dealers – due to the scarcity of available archives –, public auction sales are easier to access. This paper provides a systematic review of all Parisian sales between 1861 and 1869 in which artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace were sold. The corresponding catalogues were matched with the minutes of the sales – a specifically French source providing unique information on sellers, buyers and prices of the sold objects. The complete dataset with the description of artefacts and protagonists is available online.

Nineteenth-century Western penetration into East Asia saw a peak during the Second Opium War (1856-1860) when British and French troops fought to expand their privileges in China.1 The war ended in Beijing in October 1860 with the looting and burning of the Yuanmingyuan, one of the official seats of government of the Chinese Emperor to the northwest of the Chinese capital. Until today, it is unknown precisely how many objects were looted by members of the allied troops, how many were taken away by Chinese looters and how many destroyed during and after the looting. Thousands of these objects – figures up to over a million have been suggested2 – were brought to Europe and are today in Western museums and private collections. So far, little research has been conducted on the fate of these objects, and current publications mainly focus on British collections.3 Not much is known about the quantity of objects that reached Europe, about the market mechanisms in the West, the collectors that purchased the artefacts from the Summer Palace, as well as the paths taken by the objects in the years after 1860: which objects arrived in Europe? In whose hands were they at what time? When did they change hands? Where are they today? While it is difficult to trace the marketing of the artefacts sold through dealers – due to the scarcity of available archives –, public auction sales are easier to access.

This paper provides a systematic review of all Parisian sales between 1861 and 1869 in which artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace were sold.4 The corresponding catalogues were matched with the minutes of the sales – a specifically French source providing unique information on sellers, buyers and prices of the sold objects.5 The complete dataset with the description of artefacts and protagonists is available online.6 This article discusses the early dispersion of the Yuanmingyuan objects on the European market with a focus on Paris.7 It aims to trace early sellers and buyers in order to contribute to an understanding of the former market structures and the objects’ movements. As public awareness about the importance of knowledge about object biographies is growing, and museums begin to research the provenance of their holdings,8 this could also be a starting point to identify objects originating from the Summer Palace in museum collections.

The Yuanmingyuan northwest of Beijing had been the residence and administrative centre of the Chinese Emperors since the Qianlong Emperor (reigned 1735-1796).9 The entire garden complex covered an area of 3.5 square kilometres. It was a huge palace compound with hundreds of small gardens, lakes, bridges, halls, pavilions, temples and palaces, among them European-style buildings and fountains, which had been designed by the Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione between 1747 and 1766. Thousands of unique artefacts, literary works and Imperial insignia were stored in the palace complex that was sacked by French and British army regiments on 7 and 8 October 1860, at the end of the Second Opium War and after almost three years of intermittent war in China.10 The allied troops consisted of over seventeen thousand men, and at least five thousand were engaged in the sacking, among them British, Indian and French soldiers.11 They mainly concentrated on items they could easily carry and were interested in objects of high material value (such as silk, pearls, gold, ivory or jade), in objects for personal use such as furs or watches, and in objects of political value - souvenirs of the Emperor of China such as state robes or seals.12 Before opening the grounds to their soldiers, the officers selected several hundred items for French and British royalty.13

This “official” loot reached Europe from early 1861 onwards.14 It was delivered to Queen Victoria in London and Emperor Napoléon III and his wife Eugénie in Paris. In the case of Britain, the artefacts from China were absorbed into the existing Royal Collection (which already held many items of Chinese decorative art collected by George IV). In France, between six hundred and eight hundred objects were presented to the emperor and his wife.15 A few political and military items went to Napoléon III, but most of the loot was given to Eugénie, in gratitude for her assistance with medical supplies during the war.

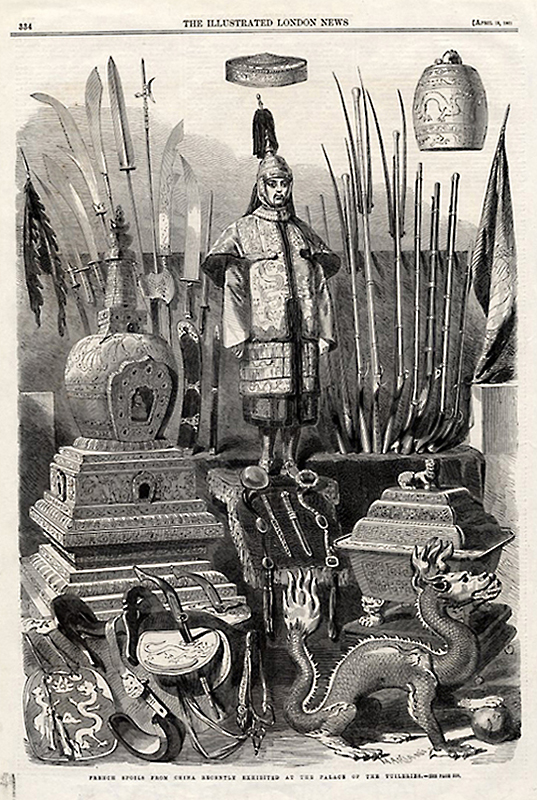

In contrast to Britain, the French objects were publicly exhibited in the Tuileries Palace between February and April 1861 (fig. 1). After the public exhibition, Eugénie established a small museum inside the private family wing of the Château of Fontainebleau, the “Musée chinois”, where the objects remain until today.16 The Tuileries exhibition was a big success and attracted many visitors.17 They could admire military equipment, imperial sceptres and arms “in pure gold with stones of jade (...), works of cloisonné surpassing all previously known dimensions, china in all shapes and from all periods, perfectly shaped jade objects of rare sizes”.18 The prompt exhibition of the loot in France was accompanied by press reviews that give an impression of the public perception of the objects and the circumstances of their acquisition. In Le Monde Illustré on 23 February, Allongé presents the exhibition of the Imperial objects as “one of the strangest events”, mentioning above all the enormous size and precious material but also the “perfect craftwork” of the enamel and jade objects and the age of the porcelain.19 In his review published in the Gazette des Beaux Arts on 15 March, China scholar Guillaume Pauthier points out the uniqueness of the collection (unique even in China), praises its high technical quality and aesthetic as well as art historical value (using the term “art chinois” for the first time and therefore rendering “China equal to Europe in cultural prestige”20) while expressing at the same time his regrets regarding the displacement of the objects and the dispersion of the whole collection.21 This reflects the special market status of the objects in terms of material and the controversy in which the objects were mired in France from the moment of their arrival – which had an impact on the way they were handled on the market. On the one hand, we observe cultural appreciation and a fascination for the unknown cultural treasures. On the other hand, we hear criticism of the forced dispersion of an Imperial collection that was shared by many other contemporaries (among them none other than Victor Hugo22) and that included a critique of the French engagement in the war.23

Fig. 1: French Spoils from China Recently Exhibited at the Palace the Tuileries, Illustrated London News, 13 April 1861.

The objects acquired by members of the army for their personal use began to arrive in Europe at the same time as the official selection. Part of it was displayed in military museums or kept as souvenirs and curios in family collections.24 The remainder appeared on the art market and was sold in the 1860s and later by dealers and at auction.

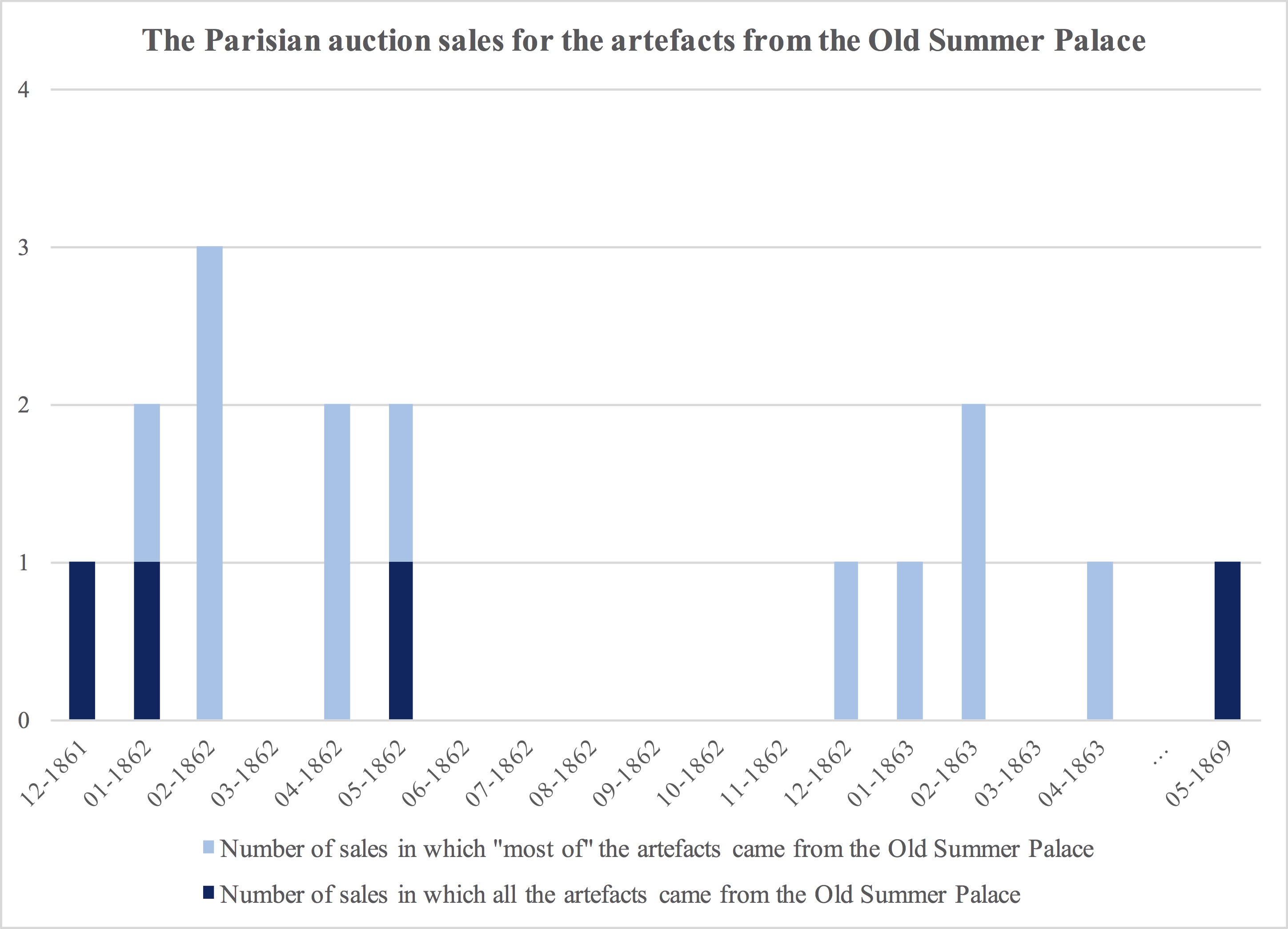

The results of our search were striking: the auctioning of Chinese imperial objects from the Summer Palace began very quickly after the return of the troops, as early as in late January 1861. This means that the looters started very soon to transform the war booty into cash and to capitalise on the economic value of the objects.25 As a matter of fact, the first auction sale of artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace took place in London as early as on 18 April 1861 at Phillips,26 while the first known auction in France took place at the Hôtel Drouot on 12 December 1861. By the end of 1862, London saw seventeen auctions (three at Philips and fourteen at Christie, Manson & Woods27) while eleven were held in Paris (all at the Hôtel Drouot). The following graph (fig. 2) and the appendix of the paper display the number of Parisian auction sales in the 1860s.

After the first sale of artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace in December 1861, ten further sales followed in 1862, avoiding the usual summer lull in the market between July and October. In 1863, four more sales took place. From 1864 to 1869, there was no more auction until the Negroni sale in May 1869. By matching the catalogue with the minutes of the sales (if available), details on the identity of the persons involved in the sales (auctioneers, experts, sellers) can be revealed.

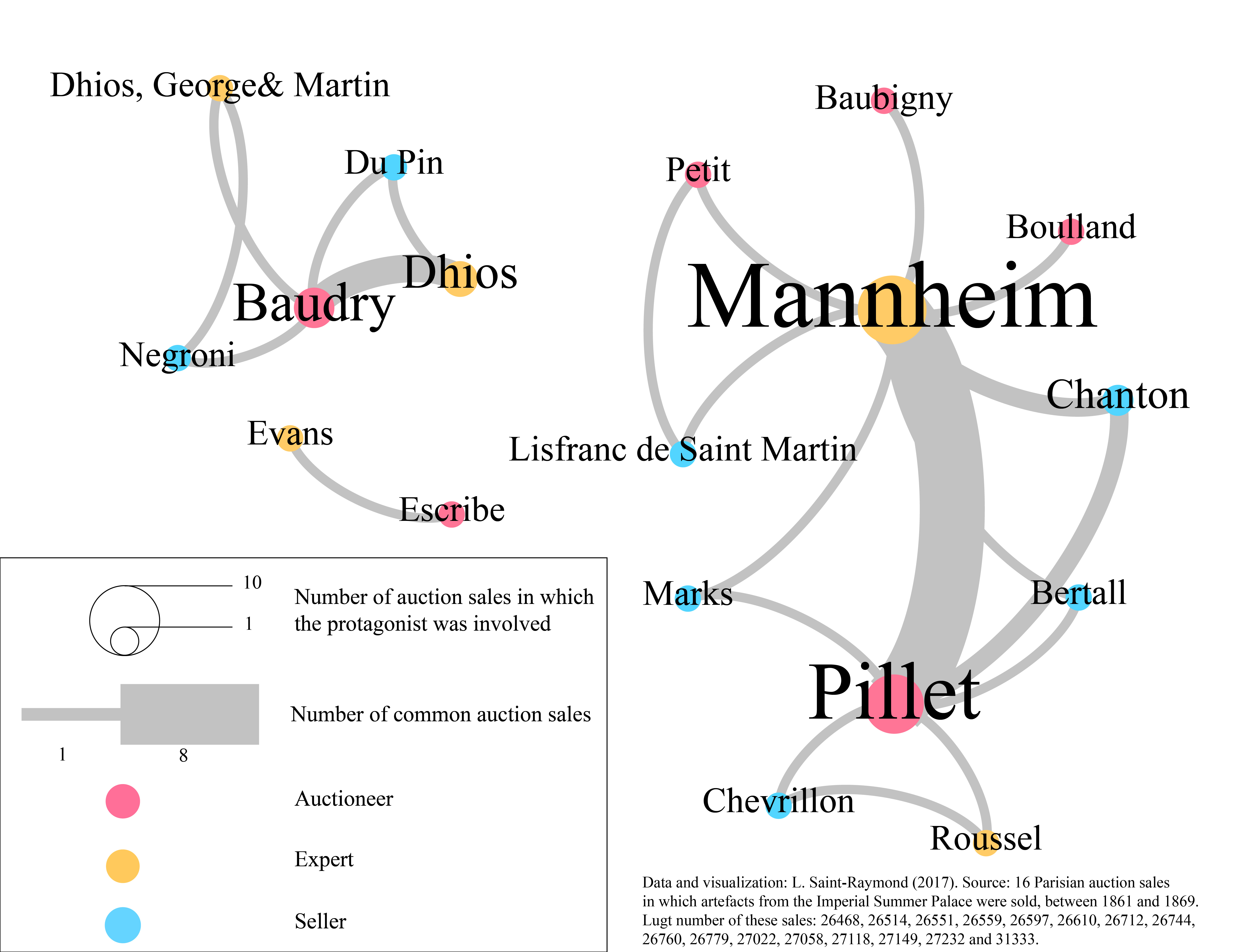

The network (fig. 3) shows the protagonists of the sixteen identified sales that took place between 1861 and 1869. The auctioneer Charles Pillet (1826-1887) was chosen for the majority of the Parisian sales (eight of them) along with the expert Charles Mannheim (1833-1910) (for seven auctions). The latter was also a dealer and often acted as expert and seller at the same time. Apart from this core, the expert J.M. Dhios and the auctioneer Louis Édouard Baudry acted for four Parisian sales.28 The name of the seller was added to this network whenever it differed from that of the expert in the minutes. For the ventes composées, the composite sales that gathered artefacts belonging to different consignors, the minutes of the time do not list the sellers but only the person acquiring it (requérant). As the experts of the auctions were very often art dealers themselves it is therefore difficult to know whether they acted as a requiring person for a composite sale or as a seller for their own artefacts. This was the case in some auction sales for which it is impossible to decide whether Charles Mannheim and Charles Evans sold their own stock or acted as mere experts and requérants.29

Fig. 2: Number of Parisian auction sales regarding artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace, from 1861 through 1869.

From the available and interpretable minutes, some interesting information about the sellers emerges. Only two army members sold their loot at auction: Colonel du Pin on 26 February 1862 and (former) Captain J. L. de Negroni on 28 and 29 May 1869. Both had been very active in the looting of the Summer Palace: Charles-Louis Du Pin (1814-1868) was head of the French topographical service in the Second Opium War and a member of the allied troops sacking the Yuanmingyuan,30 and Jean-Louis Negroni acknowledged that he undertook a “collection” at the Summer Palace for “patriotic reasons”.31 These two army members chose Louis-Édouard Baudry (1825-1881) and Dhios to set up their sales. However, the most numerous sellers at auction were dealers, who preferred Pillet and Mannheim. The Parisian importer of Chinese items Alphonse Chanton32 organised two auction sales in February and April 1862. The Paris-based dealer and forwarding agent Antoine Chevrillon33 set up a sale in February 1862, as did Alphonse Joseph Lisfranc de Saint Martin (1830-?), who had a highly confidential forwarding business.34 Finally, a certain M. Marks, “dealer from London”, held a sale in Paris in April 1863. He was very likely Murray Marks (1840-1918), a London-based curiosity dealer who traded at 21 Sloane Street by 1864 (not to be confused with his father Emanuel Marks, also an ‘importer of antique furniture, Sèvres, Dresden, oriental China & Curiosities‘). Murray Marks was in partnership with the Durlacher Brothers in the 1870’s when they traded at 395 Oxford Street in London. Interestingly, Durlacher is recorded as buyer of many high-priced objects from the Yuanmingyuan at the Christie’s auctions in 1861 and 1862.35 Mobility of the Summer Palace loot between Great Britain and France can therefore be assumed.

Fig. 3: Network of the auctioneers, experts and sellers, who organized the Parisian auction sales in which some artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace were sold, between 1861 and 1869.

All auction catalogues of these dealers’ sales did not name the consignors (unlike those from the members of the army). Their names can only be revealed through the minutes of the sales.

The seller of the first Parisian auction had an unusal background. He was neither a former member of the allied troops nor a dealer but “Albert Bertall, artiste”, as the minutes state. This was the pseudonym of Charles Constant Albert Nicolas d’Arnoux de Limoges Saint-Saëns (1820-1882), who was an illustrator, engraver, caricaturist and owner of a Parisian photography workshop. We still don’t know how he happened to own looted artefacts, but Bertall was no stranger to the Hôtel Drouot, as in 1858 he had written and illustrated an article depicting Drouot as a temple of speculation and a genuine stock exchange for art.36 Apart from the identity of the seller, the Bertall sale was also remarkable for the artefacts themselves and for the way they were sold. Indeed, its catalogue represents an exact opposite of all the other auction sales in this context.

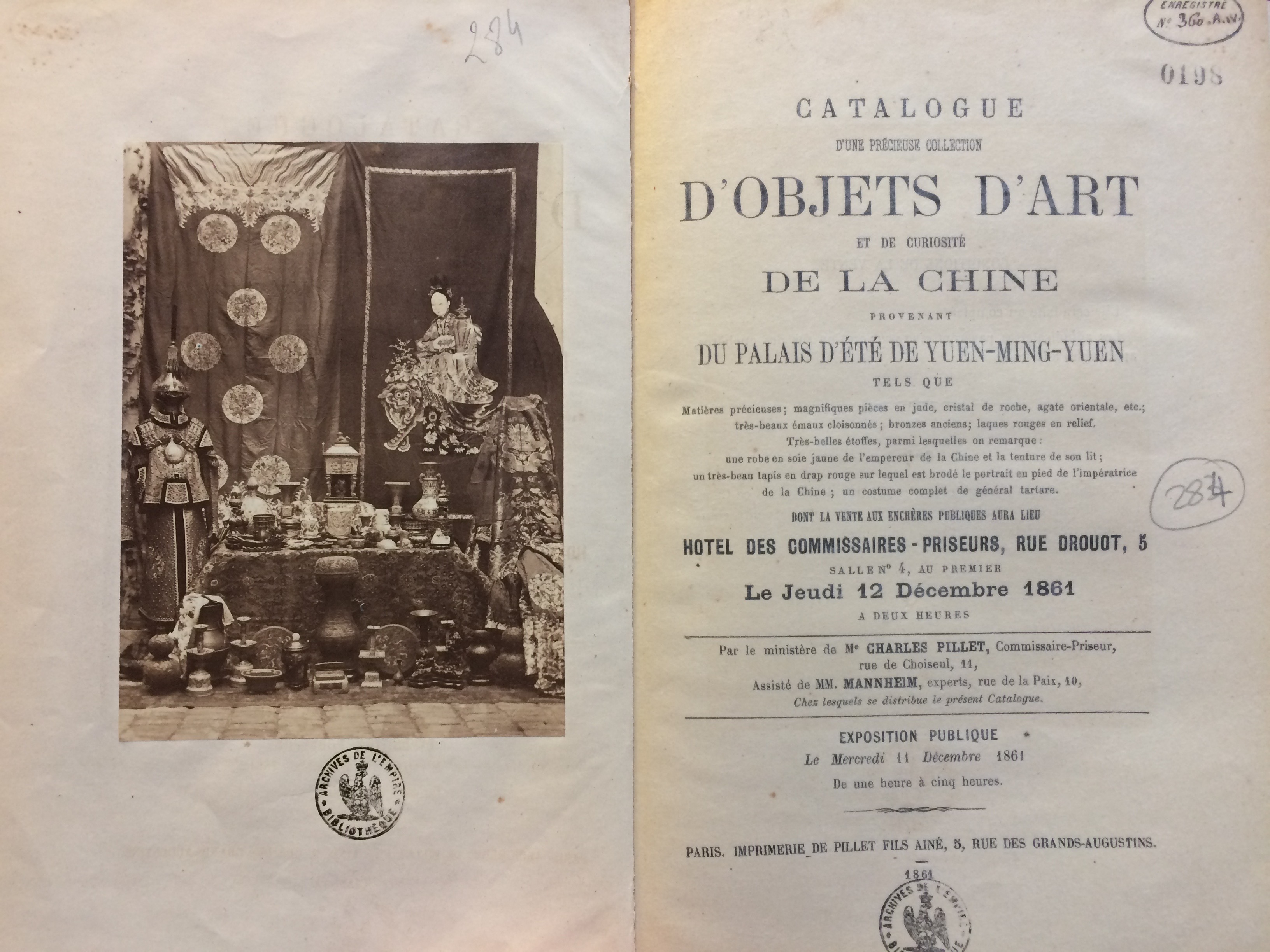

In order to understand how the artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace were sold at auction, let us consider the Bertall sale as a counterexample. The copy preserved at the Bibliothèque de l’INHA in Paris includes a special feature unusual for its time: a photograph of some of the artefacts offered at auction, opposite the title page (fig. 4).

This photograph – probably taken by Bertall in his workshop or in a courtyard of the Hôtel Drouot (see the pavement) – does not appear in the copy of the catalogue held in the library of the École des Beaux-Arts. We can thus presume that there were two types of catalogues (with and without picture), targeting different potential buyers, or that Bertall embellished his personal copy with the image. In any case, the presence of a picture was highly unusual: for auction sales of Asian artefacts in Paris, illustrated catalogues do not appear before the early 1890s.37 Even London auction catalogues of the 1860s usually do not include photographs or other images of the artefacts on offer.

Fig. 4: Pages 2 and 3 of the Bertall catalogue, 1861, dimensions of the catalogue: 22x14.5 cm, dimensions of the photograph: 12.4x9.1 cm, Paris, INHA Bibliothèque, VP/1861/198. Photograph by L. Saint-Raymond.

The singularity of the Bertall sale also stems from the fact that all artefacts originated from the Imperial Summer Palace. Only three other catalogues mention an exclusive provenance from the Palace for each item in the sale.38 The majority of the sales stated in their titles that “most of” of the artefacts were from the Yuanmingyuan, without mentioning precisely which ones (fig. 3). In an even more nebulous approach, some sellers deliberately hid the loot of the Imperial Summer Palace, like Alphonse Chanton or J.-L. Negroni. The two auction catalogues by Chanton (1862-02-03 and 1862-02-04 [Lugt 26659], and 1862-04-28 and 1862-04-29 [Lugt 26744]) are particularly simplistic: the items are unnumbered and undifferentiated, and the titles avoid any mention of the Summer Palace. The provenance only surfaces at the very end of the catalogue, stating that “a large part of these artefacts come from the Imperial Palace”.39 Captain J.-L. Negroni was even more cautious with the provenance. In a first auction sale he organised in May 1864, the loot from the Yuanmingyuan was not indicated at all: the title only mentions some “precious artefacts from China, composing the collection of M. de Negroni, dismissed captain”.40 Five years later, in 1869, Negroni organised another auction whose catalogue stated explicitly that the artefacts were coming from the Imperial Summer Palace.

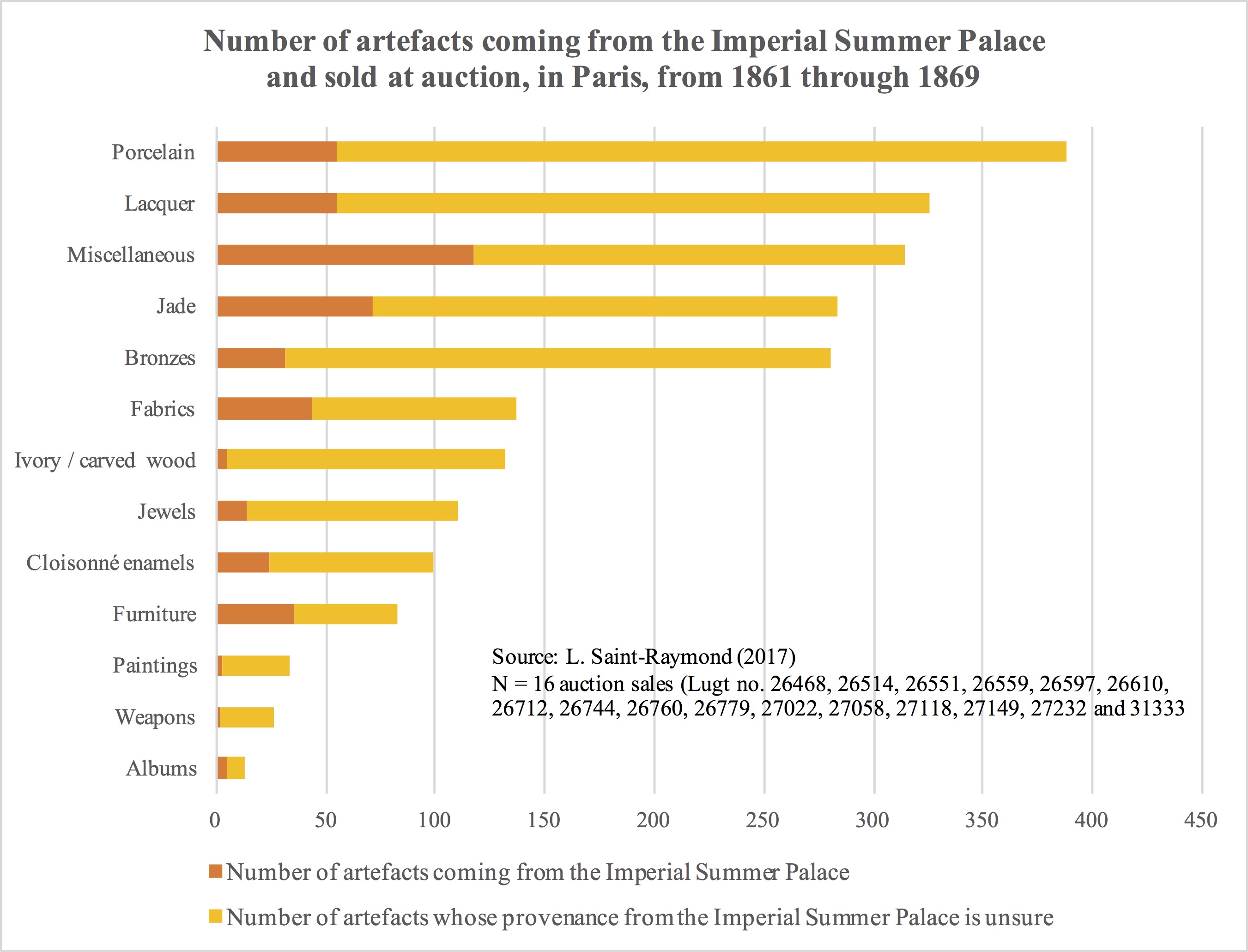

This blurring of provenance is also reflected in the description of the artefacts in the catalogues: only 463 items out of 2,224 sold between 1861 and 1869 at auction in Paris were clearly indicated as originating from the Yuanmingyuan – whereas the remaining 1,761 were merely “mostly” from the Imperial Summer Palace. This vague denomination allowed sellers to introduce some Asian artefacts into the sale, whose real provenance was unlikely to be from the Yuanmingyuan but which could now be associated by the purchasers with being “most probably from the Imperial Palace”, in particular porcelains, bronzes, lacquerwork objects and jade artefacts (fig. 5).

The same vagueness can be found in the description of the artefacts’ country of origin. Indeed, while thirty-four percent of the items were explicitly described as Chinese, fifteen percent of the objects in the catalogues classified as coming “most probably from the Yuanmingyuan” or “more or less precisely from the Yuanmingyuan” were catalogued as Japanese. The number of unidentified artefacts amounted to 1,058 out of 2,224. It is useful to bear in mind that “looted” objects with a European provenance were also sold at these auctions, in particular jewellery, watches, snuffboxes and bonbonnières made in the eighteenth century.

To summarise, from the beginning of 1862 auction sales of artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace became a bric-à-brac, like any other auction of Asian objects in the 1860s and 1870s.41 Adding the fact that the descriptions of the artefacts were very brief and that there were no reproductions in the catalogues – except in the Bertall one – it thus seems very difficult to trace the fate of the looted artefacts as well as whether an object did actually come from the Yuanmingyuan. The information about the loot and the precision of the descriptions were so vague that in the 1870s, the provenance disappeared. For instance, in an auction of 1874, two vases were sold: while the catalogue stated that they previously belonged to the “Collection du colonel du Pin” the Yuanmingyuan as provenance was no longer mentioned.42 The same happened with objects formerly owned by the Parisian landowner and artist Jean-Baptiste Auguyot: in the 1860s, he purchased some artefacts as coming explicitly from the Summer Palace.43 However, after his death, the Asian items were sold at auction without any reference to their Imperial origin.44 The lack of reference is still an issue, as most of the objects in Chinese collections today are displayed for the museum visitor without provenance information.

Fig. 5: Categories of the 2,224 artefacts sold at auction, in Paris, from 1861 through 1869.

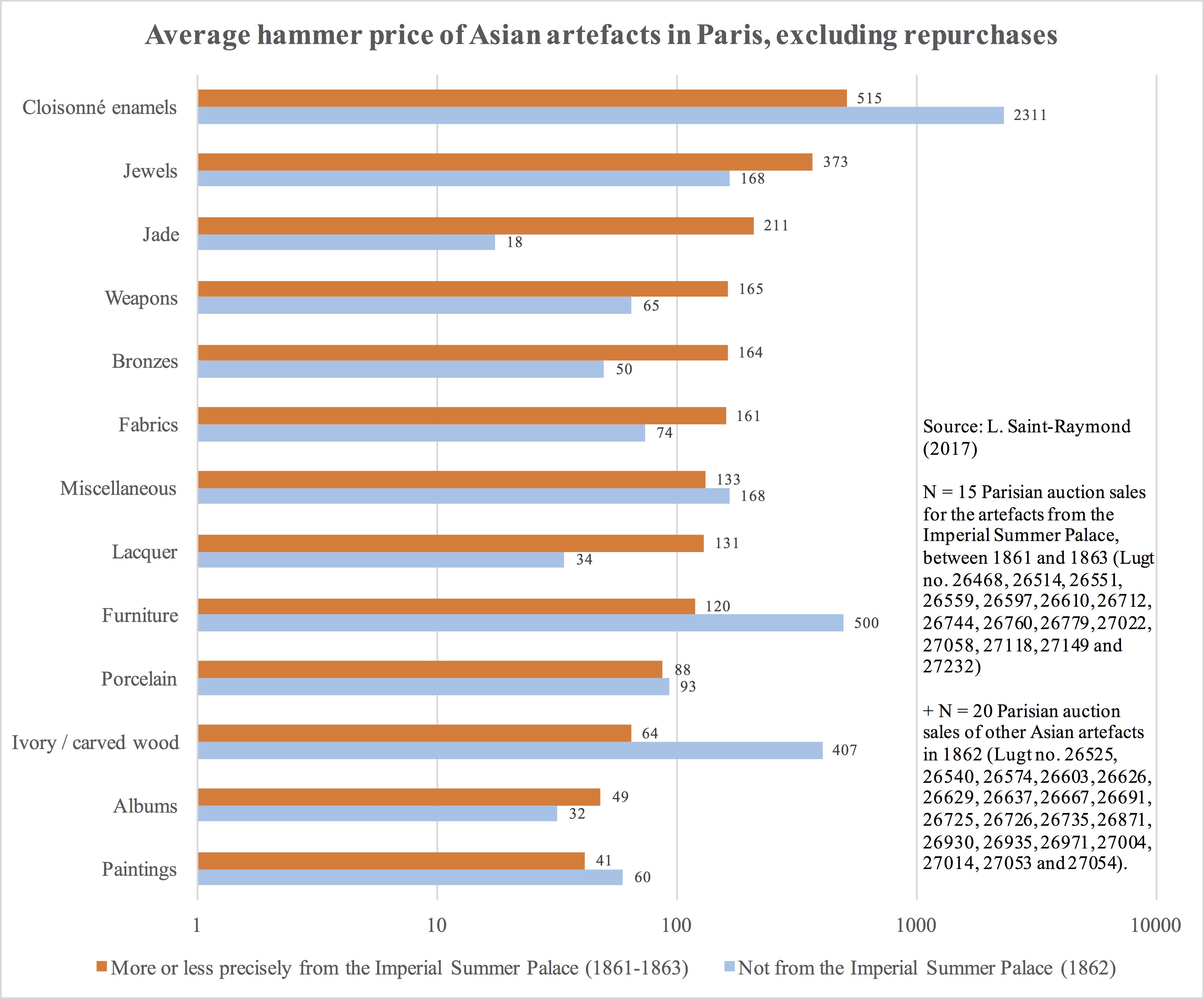

Such vagueness in the provenance could have been deliberate. Indeed, the designation “coming mostly from the Imperial Summer Palace” might thus act as a marketing tool, advertised in the titles of the catalogues and in the posters. While it is difficult to trace artefacts from one auction to another, as the descriptions are too cursory,45 it is possible to compute average hammer prices for Asian objects from the same category and compare them to those expressly from the Yuanmingyuan. A systematic review of all the Parisian auction sales for Asian artefacts was thus made for 1862,46 and the following graph (fig. 6) analyses the potential added value of the Yuanmingyuan provenance, according to the category of the object.

Fig. 6: Difference in average prices of the artefacts coming from the Imperial Summer Palace from 1861 to 1863, with those of the other Asian artefacts sold at auction, in Paris, in 1862.

Indeed, the provenance from the Imperial Summer Palace entailed a higher average hammer price for jewels, artefacts in jade, weapons, bronzes, fabrics, lacquer and albums. Of course, this price difference can be due to a difference in the “beauty” and “quality” of the artefacts. But without any illustration or detailed description of the items, it is impossible to measure such qualitative aspects. However, the Yuanmingyuan did not add additional value to all the categories: in 1862, cloisonnés, furniture, paintings and ivory or carved wood not from the Summer Palace saw a higher average price than those originating from the Imperial collection. Even more strikingly, the expert Evans gave a starting price of 2,000 francs for a lacquer cabinet from the Yuanmingyuan and failed to find a bidder: the cabinet was bought in. So too were a shawl, two dresses, a vase, a silver box and a lot of two vases, unsold during the same auction sale at starting prices of, respectively, 800, 400, 100, 500, 700 and 800 francs.47 The price levels set by the expert exceeded the buyers’ willingness to pay.

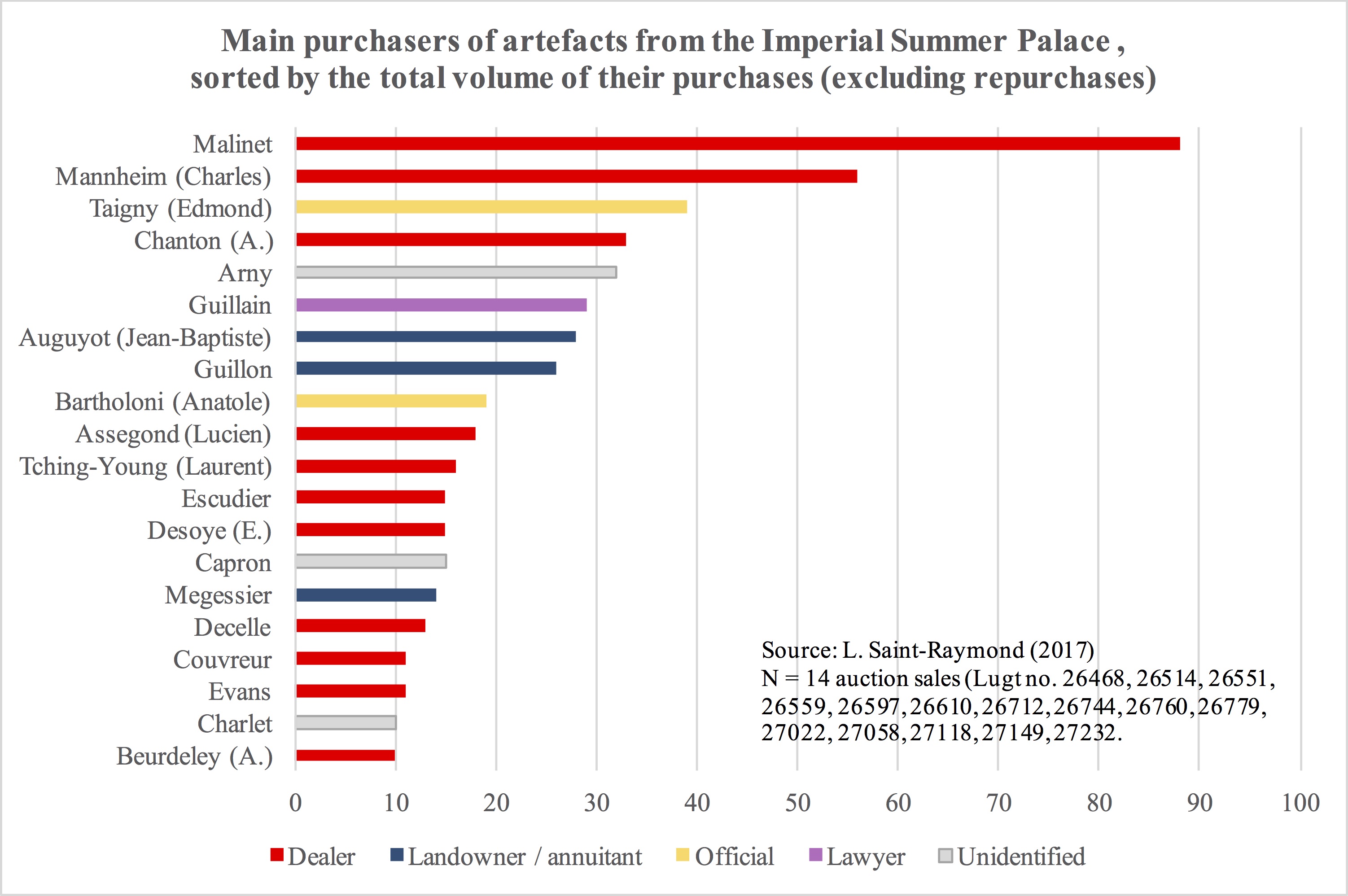

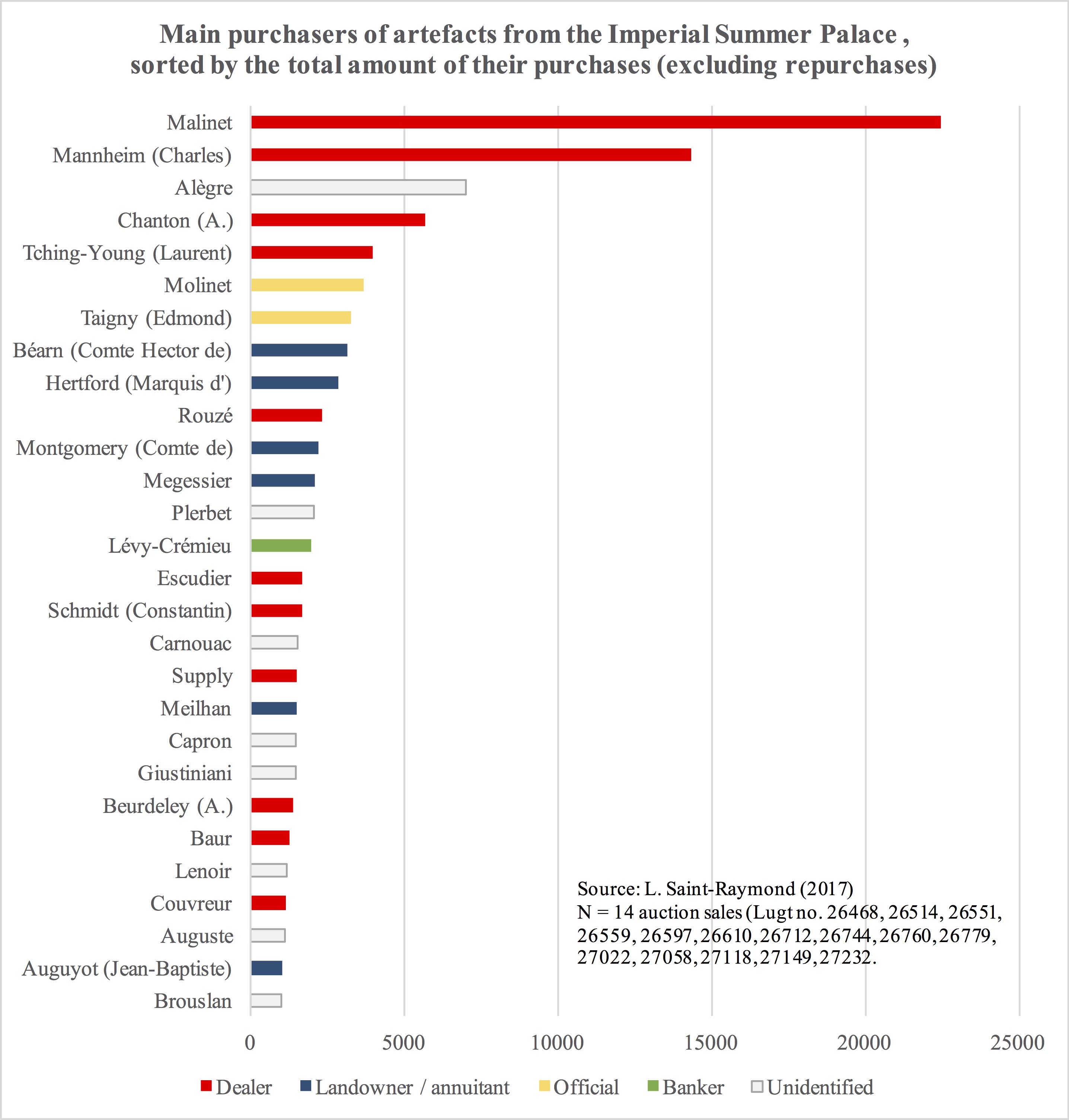

But who were the buyers who refused or accepted to pay these prices? By matching an auction catalogue with its minutes, it became possible to find the name of the purchasers and, sometimes, their address. The second step was to identify them, thanks to the Bottin du commerce,48 or the Calepin des propriétés bâties, held at the Archives de Paris.49 The Dataverse appendix gives comprehensive results of this research and constitutes a basis for any further research. For practical reasons, we will refer to the purchase by giving its identifying number in the appendix.50 The following graphs display the main purchasers of artefacts from the Yuanmingyuan, according to the number of items they bought (fig. 7) and the total amount they spent, in francs (fig. 8).

Fig 7: List of the purchasers who bought more than 10 artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace, at auction, between 1861 and 1863, excluding repurchases.

Fig 8: List of the buyers whose total purchases amounted to more than 1,000 francs,excluding the 5 per cent buyer fee, for artefacts from the Imperial Summer Palace at auction, between 1861 and 1863 (excluding repurchases). .

Not surprisingly, Parisian dealers were among the main purchasers, both in volume and value: Nicolas Joseph Malinet (1806-1886), Charles Mannheim, Alphonse Chanton, Laurent Tching-Young, Escudier and Louis Auguste Alfred Beurdeley (1808-1883) were the major marchands de curiosités who purchased much and at high prices. The dealers Desoye and Decelle were rather specialised in artefacts from China in 1862, and they bought an important quantity of artefacts (fig. 7), but at a lower price. All these dealers were interested in a very diversified range of objects and did not focus on a specific category.

In contrast, rich Parisian landowners were more interested in luxurious and ostentatious artefacts. In particular, cloisonné enamels became highly valued, after some enamels from the royal loot were shown at the Tuileries in April 1861 and entered Eugénie’s Musée chinois: as a symbol of power and prestige, they became objects of desire for the aristocracy and the upper classes.51 For instance, the banker Marc Lévy-Crémieu (1813-1886) purchased a pagoda and a pi-tong in cloisonné enamels for a total of 950 francs52 and the Count of Montgomery was the winning bidder for an incense-burner in cloisonné for 1,300 francs.53 The highest price for an artefact from the Imperial Summer Palace was achieved during the Colonel Du Pin sale for two vases or wine cups in cloisonné used as incense-burners which had been at the foot of the Emperor’s throne in the Yuanmingyuan. Unfortunately, the minutes are missing, but the annotated catalogue states that the hammer price reached 9,050 francs.54 These vases were purchased by Richard Seymour-Conway (1800-1870), the 4th Marquis of Hertford, during the Du Pin sale and are today in the Wallace Collection in London (fig.9).

Fig. 9: Unknown artist, two incense burners / imperial ceremonial wine cups with stand, China, 18th century, gold, pearls, precious stones en cabochon, wood, mother of pearl and stained ivory, London, the Wallace Collection, not on display (W112 and W113).

© The Wallace Collection.

Along with cloisonné, the artefacts in precious material were those most sought-after by very wealthy landowners such as Lévy-Crémieu, who spent 295 francs for a solid silver Foo dog,55 Megessier who bought a thousand Oriental pearls for a total of 1,250 francs,56 the Count of Béarn, the winning bidder of a large bowl in bronze for 1,890 francs,57 or a M. Alègre, unidentified, who bought a solid gold vase for 7,000 francs.58

While most of the Parisian collectors and dealers in the 1860s preferred Chinese to Japanese artefacts,59 some connoisseurs were already interested in the latter, even during the auction sales of the Yuanmingyuan looted objects.60 For instance, the architect César Daly (1811-1894) purchased two Japanese bronze vases for 260 francs61 and the Conseil d’État member and auditor Edmond Taigny (1828-1906) bought a medicine box62 and a writing box from Japan.63 Apart from these precursors of japonisme, connoisseurs with high cultural capital could also purchase some Asian bric-à-brac at auction: Philippe de Chennevières (1820-1899), newly appointed curator of the Musée du Luxembourg, bought a table, a corner cupboard, a dresser, a basin stand and wooden set for “only” 364 francs.64 The lawyer Guillain was more eclectic and purchased porcelain, lacquer boxes, screens and even a sedan chair, most of these items without any specified provenance.

If enamels and artefacts from precious materials had reached the top of the price hierarchy, albums and paintings were at the bottom (fig. 6). Indeed, these categories were not much valued before the 1890s.65 Only the sinologist and Academician Stanislas Julien (1799-1873) was interested in eight volumes about Chinese and Japanese coins which he purchased for only fifteen francs,66 and another connoisseur, Reboul from the Court of Auditors, bought five albums for a total of thirty-seven francs.67 The offering of the 1747 silk album of forty paintings representing the Yuanmingyuan suffered from this lack of interest. At the Du Pin auction, it was described as a unique copy, providing the most complete image of the Summer Palace before it was burnt.68 According to the INHA annotated catalogue, Colonel Du Pin was asking 30,000 francs (or 20,000 francs according to the BnF annotated catalogue), but the object failed to reach this reserve: the Bibliothèque Impériale happened to be the only bidder, at 10,000 francs.69 In the end, the silk album was removed from the sale and offered again at auction two months later: the catalogue stated that the starting price would be 10,000 francs.70 The minutes are missing but it seems that the Bibliothèque Impériale purchased it at this hammer price.71 Today, this album constitutes one of the great BnF treasures and can be viewed online.72

To our knowledge the above-mentioned album is the only direct purchase of a looted artefact from the Yuanmingyuan by a French public institution or museum. In Britain, the museums also did not buy directly at auction. As our research revealed, the buyers at the Parisian auctions of the 1860’s were mainly dealers who took advantage of a unique market opportunity. Private collectors played a minor role during the sales – for multiple reasons: the market was typically geared to low-priced objects and they simply may not yet have been used to invest in collecting at this level. Furthermore, collecting Asian artefacts at that time was often related to personal interaction with a dealer who had the function not only of selling interesting objects but also of sharing and spreading his expertise. As mentioned earlier in this paper, the public controversy may have had an impact on the way the Summer Palace loot was handled on the market. Together with their high material and cultural value, their provenance contributed to an increase in pricing that changed the market for Chinese art in the West. This had an immediate influence on the marketing of other objects from East Asia as it was even used as a way of enhancing the economic value of artefacts resembling those of the Imperial collection.

The reason for an almost complete lack of purchases by French institutions may lie in the absence of interest by the Crown in collecting Chinese Imperial items beyond the official loot received. As the example of Negroni shows, there was no lack of opportunities: indeed the captain intended to sell his collection to the state for a reasonable price but was rejected.73 Twenty years later, Louis Gonse (1846-1921), chief editor of the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and expert in Japanese art, expressly regretted this attitude and encouraged the government to prevent the dispersion of the collection of another foreign culture in the case of the capture of Kairouan: “It is of high importance that the Crown does not show the same lack of interest in these questions and does not act with the same indifference, the same carelessness, the same ignorance as in the case of the capture of the Summer Palace in Peking when all these incomparable marvels have been scattered to the four winds.”74

Today, the objects from the Summer Palace are dispersed all over the world. The trade in these objects has not come to an end yet. Occasionally they still appear at public auctions and contribute to diplomatic tensions between the West and China.75 Exhibited in public collections, they are deprived of their past, as in most cases their provenance is not indicated. Step by step, art market research can trace back their biographies and embed them in their historical context.

Christine Howald is a research associate at Technische Universität Berlin. Léa Saint-Raymond is a PhD candidate in Art History at Université Paris-Nanterre. Alumna of the École normale supérieure, she is agrégée in economic and social sciences.

1861-12-12 [Lugt 26468], Catalogue d’une précieuse collection d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine provenant du Palais d’Été de Yuen-Ming-Yuen tels que matières précieuses, magnifiques pièces en jade, cristal de roche, agate orientale, etc; très beaux émaux cloisonnés; bronzes anciens; laques rouges en relief. Très belles étoffes, parmi lesquelles on remarque: une robe en soie jaune de l’empereur de la Chine et la tenture de son lit; un très beau tapis en drap rouge sur lequel est brodé le portrait en pied de l’impératrice de la Chine; un costume complet de général tartare, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1861 (Hôtel Drouot, room 4, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D48E3 52; Seller: Albert Bertall).

1862-01-13 and 1862-01-14 [Lugt 26514], Catalogue d’objets de curiosité provenant du palais d’été de l’empereur de Chine. Belles Pièces en jade et autres matières précieuses; très beau Sceptre et Bâtons de commandement; Objets en laque. Très beau Meuble en laque du Japon, à hauteur d’appui, formant cabinet, d’une grande richesse d’ornementation. Riches Manteaux de cour, de l’Empereur et de l’Impératrice, en velours et soie magnifiquement brodés en or, argent et soie; Etoffes de velours et soie unis et brodés. Une très belle Selle avec tous ses accessoires, garnie de pierreries et ayant appartenu à l’Empereur. Objets en ivoire sculpté; Bronzes, Peintures sur verres; grande et belle lanterne; Porcelaines, etc. Et d’une réunion de meubles anciens en bois sculpté et marqueterie de bois; Faïences anciennes; Bustes et Bas-reliefs en marbre; Bronze et terre cuite; Tapisseries anciennes; Émaux; Bijoux, etc, Paris (Renou & Maulde) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Escribe; expert: Evans; minutes: AdP, D42E3 42; seller: Charles Evans, expert; unnumbered catalogue).

1862-01-30 and 1862-01-31 [Lugt 26551], Catalogue d’une très belle réunion d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine et du Japon tels que Vase et Autel portatifs en or massif et enrichis de pierreries; Très beau Poignard garni en or et en argent; Garniture de cinq Pièces en argent doré et émaillé à gouttelettes; Bijoux divers en or et en argent; Très beaux Laques du Japon à fond d’or, à fonds noir et aventuriné; Laques rouges de Pékin; Matières précieuses; Superbe Morceau de lapis-lazuli de Perse; Cristaux de roche; Groupes et Amulettes en agate orientale, en onix et en jade; Porcelaines anciennes de la Chine; Bronzes anciens de la Chine et du Japon et incrustés d’argent; Emaux cloisonnés; Objets très fins en ivoire sculpté; Très belles Robes de chambre en soie garnies de fourrures; Autres Robes et Soieries en pièce; Grand Tapis en soie et en drap brodés de soie et d’or à fleurs; Quantité d’Objets divers. Provenant en grande partie du Palais de Yuen-Ming-Yuen, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1862 )(Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D48E3 53; seller: Charles Mannheim).

1862-02-03 and 1862-02-04 [Lugt 26659], Notice d’une nombreuse réunion d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine et du Japon. Porcelaines anciennes craquelées; Céladon turquoise et autres décorées de personnages, telles que: Vases, Cornets, Jardinières, Plateaux, Bois, Coupes, etc; Matières précieuses, Jade, Cristal de roche, Agate orientale, Pierre de lard, etc; Bronzes japonais et chinois, dont quelques Pièces à incrustations d’argent; Très grande et belle Vasque, Vases. Fontaines, Brûle-Parfums, Flambeaux, Pagodes, etc; Vases et Cornets en émail cloisonné; Belles Pièces en laque ancien du Japon; Cabinets, Etagères, Paravents, Lits, en bois de fer, en laque et en marqueterie de Nyang-Pô, et quantité d’Objets variés, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Pillet, expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D48E3 53; seller: M. Chanton; unnumbered catalogue).

1862-02-22 [Lugt 26597], Catalogue d’une jolie réunion d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine et du Japon tels que Vases, Statuettes, Coupes, en jade de diverses nuances, en cristal de roche, etc; Belles Pièces d’orfèvrerie émaillées; Niches pour idoles, Théières, etc, en argent; Bijoux divers; Boîtes, Coffrets, Nécessaires, Ménagères, en laque de Chine et du Japon; Boîtes, Coffrets, Tabourets, etc, en laque de Chine et du japon; Boîtes, Coffrets, Tabourets, etc, en laque sculpté de Pékin; Très belle Selle japonaise en laque, accompagnée de ses Etriers, Mors, Brides, Chabraque, etc; Jardinière, Bois, Flacons, en émail cloisonné; Sculptures en ivoire; Bronzes anciens, dont une partie incrustée de filets d’argent; Quelques Pièces de Porcelaines anciennes; Très belles Robes de voyage en soie, garnies de fourrures; Robes de dames et de seigneurs de la cour du Japon, très riches; Autres Robes et Soieries en pièce, richement brodées de soie et d’or; Quantité d’Objets variés. Provenant en grande partie du palais de Yuen-Ming-Yuen, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim.; minutes: AdP, D48E3 53; seller: Charles Mannheim).

1862-02-26 to 1862-03-01 [Lugt 26610], Catalogue des objets précieux provenant en grande partie du palais d’été de Yuen-Ming-Yuen et composant le musée japonais et chinois de M. le Colonel Du Pin, Paris (Renou et Maulde) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Baudry; expert: Dhios; minutes unavailable).

1862-04-11 and 1862-04-12 [Lugt 26712], Catalogue d’une jolie réunion d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine provenant en grande partie du Palais d’Été. Belles pièces en jade; bijoux en or enrichis de perles et pierres fines; montres et tabatières en or émaillé; petits groupes d’ivoire sculpté; écrans et vases en émail cloisonné; brûle-parfums, vases, etc, en bronze; coupes, cornets, vases en porcelaine de Chine; joli petit cabinet avec incrustations de pierres précieuses; grands lits, guéridons et boîtes à thé en marqueterie de Ning-Pô; très belles soieries et fourrures; objets divers, Paris (Maulde et Renou) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 7, auctioneer: Boulland; expert: Mannheim; minutes unavailable).

1862-04-28 and 1862-04-29 [Lugt 26744], Notice d’une nombreuse réunion d’Objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine et du Japon. Porcelaines anciennes craquelées, Céladon turquoise et autres décorées de personnages, tels que: Vases, Cornets, Jardinières, Plateaux, Bols, Coupes, etc; Matières précieuses, Jade, Cristal de roche, Agate orientale, Pierre de lard, etc; Bronzes japonais et chinois, dont quelques Pièces à incrustations d’argent; Deux grandes et belles Vasques, Vases, Fontaines, Brûle-Parfums, Flambeaux, Pagodes, etc; Vases et Cornets en émail cloisonné; Belles Pièces en laque ancien du Japon; Cabinets, Etagères, Paravents, en bois de fer, en laque et en marqueterie de Ning-Pô; Grandes et belles Pièces pour ornement de jardin, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim; minutes: Adp, D48E3 53; seller: M. Chanton; unnumbered catalogue).

1862-05-02 [Lugt 26760], Collection chinoise et japonaise, Paris (Renou & Maulde) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 7, auctioneer: Baudry; expert: Dhios; minutes unavailable).

1862-05-08 and 1862-05-09 [Lugt 26779], Collection chinoise et japonaise. Pièces remarquables provenant du Palais d’Été en Jade, laque rouge de Pékin, cuivre émaillé, ivoire, porcelaine des périodes Kien-Long, Kia-King et Tao-Houang, Paris (Renou & Maulde) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 6, auctioneer: Baudry; expert: Dhios; minutes unavailable).

1862-12-13 [Lugt 27022], Catalogue d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine & du Japon. Belles perles d’Orient, Brûle-parfums, Coupes, Poignard, Couteaux, Figurines, Plaques, etc., en jade de diverses nuances, en aventurine et en pierre de lard; Bronzes anciens, tels que Brûle-Parfums, Flambeaux, Vases, Cornets, etc.; Beaux Vases, Plats, Bois, etc., en ancienne porcelaine de Chine; Tasses japonaises en porcelaine dite coquille d’oeuf; Beaux Vases et Boîtes en laque rouge de Pékin; Emaux cloisonnés; Sabres japonais; Encre de Chine; Belles Robes de soie richement brodées; Etoffes et Objets divers; Belle Tapisserie des Gobelins, à sujets chinois, style Louis XIV, tissée en soie. Quantité de ces pièces proviennent du palais d’Été et portent le Dragon impérial à cinq griffes, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1862 (Hôtel Drouot, room 4, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D48E3 53; seller: Charles Mannheim).

1863-01-08 [Lugt 27058], Catalogue d’une jolie collection d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine et du Japon, provenant en grande partie du Palais d’Été. Grand et beau vase, Jardinières et autres pièces en émail cloisonné; jades sculptés; bijoux et orfèvrerie; belle tabatière Louis XVI, en or ciselé, à sujet mécanique et à carillon; Montres anciennes; belles pièces en laque de Pékin; laques de Chine et du Japon; grande et belle Fontaine, Vases, etc, en bronze incrusté d’argent; autres Bronzes de la Chine et du Japon; Sabres japonais; Poignards; beau Meuble-étagère et Guéridons en bois sculpté; Tableau et très-beau Jeu d’échecs en ivoire sculpté; Peintures très fines sur soie et sur papier; Robes de chambre en satin garnies de fourrures; Robes faites et non faites en satin brodé en soie; Etoffes de soie en pièces; trois beaux Crêpes de Chine blancs brodés à fleurs et quantité d’Objets variés, Paris (Maulde et Renou) 1863 (Hôtel Drouot, room 4, auctioneer: Petit, expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D124E3 2; seller: Alphonse Joseph Lisfranc de Saint Martin).

1863-02-13 [Lugt 27118], Catalogue d’une collection d’objets d’art de la Chine et du Japon provenant en partie d’une Palais d’Été. Grands et magnifiques tapis en velours noir et en drape jaune, brochés or et soie à décors d’oiseaux et signes symboliques; écharpes en soie rouge brochées or; laques du Japon de nuances variées; meubles en laque de chêne; bronzes anciens: brûle-parfums, cornets, chimères, vases, pi-tongs, etc: porcelaines de la Chine et du Japon; émaux cloisonnés, émaux de la Chine; armure japonaise de cavalier, en fer laqué; armes diverses; objets en jade et en cristal de roche; objets divers; livres chinois; rouleaux, etc, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1863 (Hôtel Drouot, room 1, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Roussel; minutes: AdP, D48E3 54; seller: M. Chevrillon).

1863-02-26 [Lugt 27149], Catalogue d’une charmante réunion d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine, pièce de choix en émail cloisonné, telles que: cassolettes, vases, cornets, jardinières, etc; très belle théière en bronze incrusté d’or et d’argent; brûle-parfums, vases, coupes, groupes, flacons, colliers, etc, en lapis-lazuli, en jade de diverses nuances, en agate orientale, en corail, etc; pagode et divinités en or et en argent; montres et tabatières en or émaillé et perles fines de travail européen; jolie boîte en laque, fond d’or; porcelaines; ivoires sculptés; albums et objest divers; provenant en grande partie du palais de Yuen-Ming-Yuen, Paris (Renou & Maulde) 1863 (Hôtel Drouot, room ٤, auctioneer: Baubigny; expert: Mannheim; minutes unavailable).

1863-04-04 [Lugt 27232], Catalogue d’une très jolie collection d’objets d’art et de curiosité de la Chine. Matières précieuses, telles que: jades de diverses nuances, lapis, agate orientale, cristal de roche; cassolettes, vases, brûle-parfums, etc, en émail cloisonné de très belle qualité; vases de grandes dimensions, cassolettes, groupes, brûle-parfums en bronze ancien, dont quelques pièces richement incrustées d’or, d’argent et de pierres précieuses; porcelaines dites d’échantillons, telles que: vases en céladon bleu turquoise, vert-pomme, craquelé, etc; vases de grande dimension en porcelaine mince; gourdes et vases de diverses formes en porcelaine émaillée (famille verte) de très belle qualité; objets divers. Provenant en grande partie du Palais d’Été, Paris (Pillet fils aîné) 1863 (Hôtel Drouot, room ٤, auctioneer: Pillet; expert: Mannheim; minutes: AdP, D48E3 54; seller: M. Marks, from London).

1869-05-28 and 1869-05-29 [Lugt 31333], Collection d’objets précieux de la Chine provenant du Palais d’Été de Yuen-Ming-Yuen dont la vente aux enchères publiques aura lieu en vertu de jugement du Tribunal civil de 1e instance de la Seine, Paris (Renou & Maulde) 1869 (Hôtel Drouot, room ٢, auctioneer: Baudry; experts: Dhios, George and Martin; annotated catalogue: collection Negroni; minutes unavailable).

1 Such as the right to establish diplomate legation in Beijing, to extend trade and travel rights and to legalise the Opium trade (Britain). The Second Opium War started in late 1856 with the attack of Guangzhou and ended on 24 October 1860 with the signing of the Convention of Beijing. For a very concise summary of the war see: Greg M. Thomas, The Looting of Yuanming and the Translation of Chinese Art in Europe, in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 7 (2008): 2 (accessed 22 January 2015).

2 Louise Tythacott , Trophies of War: Representing “Summer Palace” Loot in Military Museums in the UK, in Museums & Society, 13 (2015), 469-488, here: 469.

3 James Hevia traced the phases of plunder as well as first and foremost British market activities (auctions) by focusing on the shift in meaning and the biographies of the looted objects: James Hevia, Loot’s Fate. The Economy of Plunder and the Moral Life of Objects, in History and Anthropology 6 (1994), 319-345; James Hevia, Looting Beijing: 1860, 1900, in Lydia Liu, ed., Tokens of Exchange. The Problem of Translation in Global Circulation (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999), 192-213; James Hevia, Plunder, Markets and Museums. The Biographies of Chinese Imperial Objects in Europe and North America, in Morgan Pitlka, ed., What’s the Use of Art? Asian Visual and Material Culture in Context (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2007), 129-141. Louise Tythacott researched the British Yuanmingyuan loot in British military museums: Tythacott, Trophies of War, 469-488; see also Louise Tythacott, ed., Collecting and Displaying China’s ‘Summer Palace’ in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France (New York: Routledge, 2018). Nick Pearce published amongst others on ‘Soldiers, Doctors, Engineers: Chinese Art and British Collecting, 1860-1935’, in Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History 6 (2001), 45-52 and recently: From the Summer Palace 1860: Provenance and Politics, in Louise Tythacott, ed., Collecting and Displaying China’s ‘Summer Palace’ in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France (New York: Routledge, 2018). 38-50. Greg Thomas worked on the translation of looted art into the Western art discourse and its display in Europe, especially in France: Greg M. Thomas, Looting (as fn. 1); Greg M. Thomas, Regrouping. Displays of Loot from “Yuanmingyuan”, in Proceedings of CIHA Nürnberg (2012), 509-513. Since 2016, Kate Hill has run a website entitled “Yuanmingyuan Artefact Index “ (http://www.yuanmingyuanartefactindex.org/copyright/), a digital repository on artefacts linked to the Yuanmingyuan.

4 This review was compiled using the Art Sales Catalogue Online, the INHA library and the BnF. All auction catalogues whose titles contain the key words “Palais d’Été”, “Yuen-Ming-Yuen” or “Summer Palace”, were collected at the library of the Institut national d’histoire de l’art (INHA), the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the library of the École des Beaux-Arts, Paris.

5 Where available, these minutes are preserved in the Archives de Paris.

6 Léa Saint-Raymond, The Yuanmingyuan Loot at Parisian Auctions in the 1860s: Artefacts, Hammer Prices, Sellers and Purchasers, Harvard Dataverse, 2018, doi:10.7910/DVN/0COI5J (available under: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi%3A10.7910%2FDVN%2F0COI5J)

7 For a comparison of the Parisian and the London market activities between 1860 and 1862 see Christine Howald, The Power of Provenance. Marketing and Pricing of Chinese Looted Art on the European Market (1860-1862), in Charlotte Guichard, Christine Howald and Bénédicte Savoy, eds., Acquiring Cultures. Histories of World Art on Western Markets (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2018) (forthcoming).

8 See for example the project at the Museum für Völkerkunde, Hamburg “Plünderware aus chinesischen Palästen”, presented by Susanne Knödel at the workshop “Provenienzforschung zu ostasiatischer Kunst. Herausforderungen und Desiderata” in Berlin on 13 October 2017 (available under: https://voicerepublic.com/talks/provenienzforschung-zu-ostasiatischer-kunst-herausforderungen-und-desiderata-161f54fc-cb3b-4843-b4dc-c4b94608f158, accessed on 10 November 2017).

9 The Imperial Gardens at the Old Summer Palace consisted of three gardens: the original Garden of Perfect Brightness (Yuanmingyuan), the Garden of Eternal Spring (Changchunyuan), where the European-style palaces were located, and the Elegant Spring Garden (Qichunyuan).

10 These are the predominant days of the looting. British sources report that the French, who arrived at the end of September before their allies, already looted during the preceding days. Even after the 8th, plundering continued.

11 Tythacott, Trophies of War, 469. Wong speaks of around ten thousand troops, see: Young-Tsu Wong, A Paradise Lost. The Imperial Gardens of Yuanming Yuan (Honolulu: Springer, 2001), 142. A third of the British army were Indian.

12 Robert Swinhoe, Narrative in the North China Campaign of 1860 (London: Smith, Elder and Co.,1861), 299: “The French camp was revelling in silks and bijouteries (...). One French officer had a string of splendid pearls, each pearl being of the size of a marble (this he afterwards foolishly disposed of at Hong Kong for 3,000 pounds), others had pencil-cases set with diamonds; others watches and vases set with pearls.” See also page 307: “New rooms were constantly being found as the marauders extended their researches, still untouched and filled with old bronzes, clocks, enamelled jars, and an infinity of jade-stone curiosities. To these the plunderers rushed with eagerness.”

13 James Hevia, English Lesson. The Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003), 76.

14 The exact date of arrival is unknown. But taking into account the transfer time from Beijing to Tianjin or Dagu, and the fact that before 1871 (when a steamboat line was established) the passage from China to Europe took at least one hundred days (http://www.dhm.de/archiv/ausstellungen/tsingtau/katalog/auf1_1.htm, accessed 27 March 2017), it is unlikely that looted objects from the Yuanmingyuan arrived in Europe before the end of January 1861.

15 According to Xavier Salmon, former directeur du patrimoine et des collections at the château in Fontainebleau: http://culturelocker.com/story/2013/France-Fontainebleau.html (accessed on 7 June 2016).

16 The museum was stripped of its original furniture after 1879 but all rooms were reconstructed in the 1990s, see: Vincent Droguet, Empress Eugénie’s Chinese Museum at the Château of Fontainebleau: An Unusal Décor in the ‘House of the Ages’, in Tythacott, Collecting and Displaying, 145f.

17 Guillaume Pauthier, Des curiosités chinoises exposées aux Tuileries, in Gazette des Beaux-Arts 9 (1861), 363-369. Pauthier speaks about a “foule compacte qui ne permettait pas le plus souvent de (...) voir [les objets] de près” (p. 365).

18 ”En or massif avec des pierres de jade (...), travaux d’émail dépassant les dimensions connues, porcelaines de toutes formes et appartenant aux différentes époques de l’art chinois, pierres de jade d’un travail parfait et d’une rare grosseur”, see: Allongé, Exposition des présents offerts à Leurs Majestés par l’armée expéditionnaire de Chine, in Le Monde Illustré, 23 February 1861, 128.

19 Ibid.

20 Greg M. Thomas, Looting, 510.

21 Pauthier, Curiosités, 363: “Je ne puis m’empêcher d’exprimer d’abord ici le regret, et un regret profond, que ces objets d’art soient tombés, avec tant d’autres, entre les mains de nos soldats, par le droit brutal de la guerre; et, ensuite, que les collections accumulées depuis plus d’un siècle dans les palais d’été des empereurs, collections assurément uniques en Chine, pour l’abondance et la rareté des objets, aient été disperses à tous les vents, et qu’ils n’en soit arrivé en France qu’un faible échantillon, lequel, à lui seul, est loin de suffire à donner une idée complete de l’art chinois.”

22 Victor Hugo, Lettre au capitaine Butler (25 November 1861). The letter can be found in Che Bing Chiu, Yuanming Yuan. Le jardin de la Clarté parfaite (Besançon: Imprimeur Eds De L’, 2000), 11-12.

23 See also: Ines Eben von Racknitz, Die Plünderung des Yuanmingyuan. Imperiale Beutenahme im britisch-französischen Chinafeldzug von 1860 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012), 249ff.

24 See: Tythacott, Trophies of War, 470ff; Hevia, Looting Beijing, 192-213; Kate Hill, Chinese Ceramics in United Kingdom Military Museums, in The Oriental Ceramic Society Newsletter (20.05.2012), 11-14.

25 For more information on the commodification of the Yuanmingyuan loot see: Hevia, Plunder.

26 These are the first auctions mentioning the provenance of the Summer Palace. According to Thomas (Looting, 29) as early as in December 1860 (20th) and January 1861 (11th) Christie, Manson and Woods auctioned objects from the Summer Palace. This could not be verified in Christie’s archive.

27 For a detailed list of these auctions see: Howald, Power of Provenance.

28 These are the sales with the following Lugt Numbers: 26610, 26760, 26779, 31333 (see appendix).

29 These are the sales with the following Lugt Numbers: 26514, 26551, 26597 and 27022 (see appendix).

30 In 1862, he published a report of his time in China under the pseudonym Paul Varin (Expédition de Chine [Paris: Lévy frères, 1862]). He was appointed colonel after the sacking on 7 November 1860. Du Pin was previously lieutenant-colonel, Chief of the 17th Military Division during the Crimean Military campaign (see: César Lecat Bazancourt, L’expédition de Crimée jusqu’à la prise de Sébastopol: chroniques de la guerre d’Orient, vol. 1 [Paris: Myot, 1857], 2). After the China expedition, he became commander of the counter-guerilla in Mexico in March 1863 (see: La contre-guérilla française au Mexique [Paris: A. Chaix, 1866], 5).

31 J. L. Negroni, Souvenirs de la campagne de Chine (Paris: Renou & Maulde, 1864), 7.

32 The minutes of the sale state that Chanton was a dealer. According to Manuella Moscatiello, Alphonse Chanton was an “importer of items from China and Japan (Manuella Moscatiello, A craze for auctions. Japanese art on sale in 19th century Paris, in Andon, 90 [2011], 43).

33 Antoine Chevrillon was a dealer, according to Geneviève Lacambre (Geneviève Lacambre, A few notes on the Japanese paintings shown at the 1867 Exposition Universelle in Paris, in Studies in Japonism, 33 [2013], 20) and a commissionnaire en marchandises as per Manuella Moscatiello (Moscatiello, Craze, 43).

34 The minutes of the Lisfranc sale state that he was just a “landlord” (propriétaire). However, the Calepin des propriétés bâties for his address – 17, rue d’Enghien, in Paris – mentions that he was a “commisR”, i.e. commissionaire or forwarding agent (Archives de Paris, D1P4 381). His activity was not referenced in the Bottin du commerce.

35 Murray himself had a business relationship with Philippe Sichel (1840-1899). He often bid at auction on behalf of the South Kensington Museum and sold several objects to the museum during the 1870s and 1880s. See Mark Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique & Curiosity Dealers (Glasgow: The Regional Furniture Society, 2009), 90, 135f.; Roy Davids and Dominic Jellinek, Provenance. Collectors, Dealers & Scholars in the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain & America (Oxon: The Old Forge, 2011), 312.

36 Albert Bertall, La Bourse des Arts, rue Drouot, in Journal amusant, 113 (27.02.1858), 1-5.

37 Léa Saint-Raymond, La création sémantique de la valeur: le cas des ventes aux enchères d’objets chinois à Paris (1858-1939), proceedings of the conference ‘Déplacements et créations sémantiques Chine – France – Europe’ (Paris: Éditions de la rue d’Ulm, forthcoming).

38 These auction sales are the Evans sale [Lugt 26514], which happened right after the Bertall one, the anonymous sale of May 1862 [Lugt 26779] and the Negroni sale in 1869 [Lugt 31333].

39 Lugt 26659, 5 and Lugt 26744, 5.

40 1864-05-18 to 1864-05-21 [Lugt 27951], Catalogue d’objets précieux de la Chine composant la collection de M. de Negroni, capitaine démissionnaire, Paris: Renou & Maulde, 1864 (Hôtel Drouot, room 5, auctioneer: Pillet and Langoit; expert: Mannheim). Negroni published a catalogue of his collection before the sale, in which the loot of the Yuanmingyuan was explicit: J. L. de Negroni, Souvenirs de la campagne de Chine (Paris: Renou et Maulde, 1864).

41 Léa Saint-Raymond, Les collectionneurs d’art asiatiques à Paris (1858-1939): une analyse socio-économique, in Marie Laureillard and Cléa Patin, eds., Orient Extrême: regards croisés sur les collections modernes et contemporaines (Paris: Éditions de l’Harmattan, 2018, forthcoming).

42 1874-02-26 to 1874-02-28 [Lugt 34577], Collection de tableaux anciens et modernes provenant de collections célèbres, objets d’art et d’ameublement dépendant de la succession de M. B***[Blin], Paris, XXX, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, rooms 8 and 9, auctioneer: Pillet and Darras, experts: Féral and Mannheim, item no. 58 p. 38. These two vases may correspond to lot 141 of the du Pin sale [Lugt 26610].

43 See the Dataverse appendix, ID_8, 138, 197, 259, 263, 273, 278 and 308.

44 1875-03-10 and 1875-03-02 [Lugt 35409], Catalogue de tableaux anciens et modernes, émaux de Limoges, porcelaines de la Chine et du Japon, objets d’art formant la collection de feu M. Auguiot, Paris, Pillet fils aîné, Paris, Hôtel Drouot, room 8, auctionner: Pillet, experts: Féral and Mannheim.

45 The Negroni auction sales in 1864 and 1869 would have allowed us to compare prices for the same artefacts. Unfortunately, the minutes of the 1869 Negroni sale are missing and, as a consequence, we cannot compare the hammer prices of the same artefacts with and without their provenance listed.

46 The results may be found online: Léa Saint-Raymond, Les ventes aux enchères d’objets asiatiques à Paris entre 1858 et 1913: statistiques et listes des principaux acquéreurs , Harvard Dataverse, 2016, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/G96SRI, accessed on 23 October 2017.

47 Lugt 26514, minutes of the sale: AdP, D42E3 42.

48 Annuaire-Almanach du Commerce, de l’Industrie, de la magistrature et de l’administration ou Almanach des 500,000 adresses de Paris, des départements et des pays étrangers (Didot-Bottin), Paris, Firmin Didot Frères, fils et Cie, 1862.

49 The Calepin des propriétés bâties is a fiscal document which gives the identity of the inhabitants of any Parisian building, from 1852 onwards. It is preserved at the Archives de Paris (D1P4).

50 Léa Saint-Raymond, Yuanmingyuan Loot (as fn. 6).

51 Léa Saint-Raymond, Collectionneurs.

52 ID_2049 and ID_2050.

53 ID_2047.

54 ID_1161. The catalogue describes them as follows: “Deux vases brûle-parfums en émail cloisonné, à goutelettes, bronze doré. Pièces uniques comme genre de travail. Etaient placés au pied du trône de l’Empereur (3e salle du trône de Yuen-Ming-Yuen).”

55 ID_1905.

56 ID_1525 and ID_1526.

57 ID_693.

58 ID_355.

59 Léa Saint-Raymond, Création sémantique.

60 Léa Saint-Raymond, Collectionneurs.

61 ID_154.

62 Actually, this artefact was likely to be an inrō but this type of object was only described with its Japanese name in the Parisian auction catalogues from the 1880s onwards.

63 ID_480 and ID_1803.

64 ID_328, ID_332, ID_333, ID_340 and ID_344.

65 Léa Saint-Raymond, Les ventes aux enchères d’objets asiatiques à Paris entre 1858 et 1913: statistiques et listes des principaux acquéreurs, Harvard Dataverse, 2016, https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/G96SRI, accessed on 10 November 2017.

66 ID_1920.

67 ID_1533.

68 ID_1202. The album is described as follows: “Grand album représentant les 40 vues des palais de Yuen-Ming-Yuen, peintures sur soie, légendes en regard de chaque palais, 40 feuilles doubles, collées sur carton, de chacune 0m80 sur 0m74 (S.J.). Pièces uniques, et les seules qui nous conservent l’image des palais incendiés.”

69 Catalogue des objets précieux provenant en grande partie du palais d’été de Yuen-Ming-Yuen et composant le musée japonais et chinois de M. le Colonel Du Pin, 44.

70 ID_1493.

71 According to Greg M. Thomas the album was sold to a dealer who then sold it to the Bibliothèque Impériale, see: Thomas, Regrouping, 11.

72 Qian long (China Emperor, author of the text), Youdoun Wang (1692-1758, calligrapher) and Dai Tang (1673-1752?, painter), Ritian linyu / (Qing)Tang Dai, Shen Yuan he hua; (Qianlong yin shi; Wang Youdun dai shu), 1744, painting and calligraphy on sild, 63.3x64.4 cm, Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE FR 6-B-9, available olinle: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b55008332q, accessed on 10 November 2017.

73 As Negroni states himself in his Souvenirs de la campagne de Chine: “Nous regrettons que notre position de fortune ne nous permette pas de le prouver aujourd’hui en offrant généreusement à la France le produit de notre travail: les grandes dépenses qu’il a nécessitées nous en empêchent. Cependant nous serions prêt à faire tous les sacrifices possibles dans le cas où le gouvernement de Sa Majesté l’Empereur daignerait prendre en considération et nos bonnes dispositions et le désir de notre coeur qui serait de voir tous ces beaux objets d’art uniques, si intéressants à tant de titres, devenir la propriété de l’État.” See: J. L. de Negroni, Souvenirs de la campagne de Chine (Paris: Renou et Maulde, 1864), 8.

74 Louis Gonse, Un mot sur la Tunisie et sur l’Exposition de la Cour Caulaincourt au Louvre, in La Chronique des arts 15 (1881), 255.

75 While their public sale was not questioned 150 years ago, the question of the legitimacy of their ownership has now gained a diplomatic dimension: in 2009, the sale of two bronze animal zodiac heads from the Xiyang Lou (the European style mansion at Yuanmingyuan) - the rabbit and the rat - from the collection of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé at Christie’s in Paris provoked official Chinese anger. After the loot of 1860, the twelve bronze zodiac heads of stone sculptures that were formerly part of a water clock designed by Jesuits Giuseppe Castiglione and Michel Benoist between 1747 and 1766 vanished and began to appear on the international art market from the mid-1980s onwards. The Chinese government had previously managed to purchase all of them. But the rabbit and the rat achieved unforeseen high prices that provoked a diplomatic debate on the legitimacy of the loot itself. The two bronze heads were eventually returned to China by the industrialist and owner of Christie’s auction house, François-Henri Pinault, in 2013.