ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Meike Hopp

The structural development of commercial galleries and, more generally, of commercially used spaces for the presentation of art works as a historical architectural challenge in the first place should become an integral part of our perception. When the magazine Die Kunst spoke of “Art Dealer Palaces” in 1913, a prime example was Munich. This article will aim at reconstructing a multi-layered image through historical sources, in particular contemporary articles and reviews from architecture magazines or art journals. In fact, buildings and interiors of art dealers were passionately discussed during this period, and in some cases were even regarded as highly controversial. Several case studies will illustrate the extent to which the individual elements of presentation – wall, floor, ceiling, light, furniture, artworks and their frames were subject to a thorough revision in 1900, and the extent to which the interior design of commercially used exhibition spaces not only matched the staging concepts of museums and the Secessions, but were in fact closely linked to the idea of the museum reform movement and even established a modern private exhibition practice. While the article captures trends and peculiarities that in turn may allow conclusions to be drawn for the history of exhibition strategy in general, there is a need for more in-depth research of this neglected subject.

In his 1937 article ‘Kunsthandel und Kunstraum’, published in three parts in the journal Weltkunst, the art historian Kurt Karl Eberlein (1890-1945) complained: “Far too little attention and investigation has been focused on the degree to which the art trade is influenced by the space for art, that can even determine the format of an artwork”.1 He continued to elaborate further: “The shop as an art dealer’s shop is an important chapter in the art trade and its history. Few enquiries have been made as to how and where the artist or art dealer offered his goods and which connections existed between art shop and art collection, who had been an art dealer at all, and how the art dealer’s shop had developed.”2

Eberlein’s criticism remains valid to this day. Even though he pointed out that private galleries, “with all the tools available in technology and interior decoration [...] had an impact on the museum” and while especially the eighteenth-century auction saleroom with its roof lantern windows served as a model for European museum buildings, the architectural history of art shops and private galleries has never been explored. Located at the intersection between intimate art gallery, temporary exhibition space and commercial retail store, and thus caught in a conflict between culture, aesthetics and economy, art historians especially in Germany have completely neglected their architectural history. Neither within the wide-ranging research on the development of department store architecture,3 nor within papers on the museum reform movement,4 was the closely related architectural task of the art dealer’s commercial premises (“Bauaufgabe Kunsthandlung”) ever considered. Neither does the fairly specialized literature on younger and more specific research topics, such as architectural lighting for the presentation of artefacts5 or the cultural history of the shop window6 address any examples of art dealer’s galleries. While the complete neglect of art shops and private galleries was already criticized by Walter Grasskamp in his essay of 2003, an “Attempt of a Prehistory” of the “White Cube” after Brian O’Doherty,7 even recent literature in the field of art market studies (and corresponding monographs on merchants) pays hardly any attention to questions pertaining to the history of the gallery buildings or the interior design of commercial representation spaces for art, as well as to the topography of the art market and its spaces in urban centres.8

This article will focus on the example of Munich, reconstructing a multi-layered image through historical sources, in particular contemporary articles and reviews from architecture magazines or art journals; in fact, the buildings and interiors of art dealers were passionately discussed during this period, in some cases even regarded as highly controversial. Therefore it seems appropriate to question the widespread opinion that art dealers “followed the domestic arrangements of their customers until well into the 20th century”.9

Several case studies will illustrate below thet extent to which the individual elements of presentation – wall, floor, ceiling, light, furniture, artworks itself and their frames – designated by Grasskamp as “ingredients”10, were also subject to a thorough revision in 1900, and the extent to which the interior design of commercially used exhibition spaces not only matched the staging concepts of museums and the Secessions,11 but were in fact closely linked to the idea of the museum reform movement and even established a modern private exhibition practice. It is thus all the more astonishing that there has as yet been no academic investigation of these mutual influences, the more so since Munich art dealers and auctioneers had their exhibition rooms designed by leading museum architects12 – and this was most likely also the case in other cities. It goes without saying that in the context of this brief contribution – especially bearing in mind the precarious state of research – no final evaluation can be presented on this issue. For a wider picture, parallel developments in other German cities would have to be taken into account as well as the international dimension, which could not be included in the framework of this article. Nonetheless, these are crucial research desiderata.

When in 1901 Ernst Wilhelm Bredt (1869-1938) presented a “reform idea” of the Bavarian Arts and Crafts Association for the establishment of a permanently accessible “Studio and Exhibition Building” for representation and sales purposes of fine and applied arts located on Munich’s Coal Island (today: Museum Island),13 he was sharply criticized by the Detmold entrepreneur and collector Oskar Münsterberg (1865-1920). In Bredt‘s imagination the “Studio and Exhibition Building” was to counteract the “cancerous destruction” wrought by the completely overloaded Munich art exhibitions and to present art simply as in a “department store”. Financed by sales commissions and rentals, in small and predominantly “sober” rooms with a variety of lighting conditions, “younger and youngest” artists should be given the opportunity to choose their own décor and colour and present their works as they thought fit. Münsterberg categorically attacked Bredt’s idea of using the arts and crafts movement, which had done great “pioneering services for the advancement of all artistic endeavour and enjoyment”, as a kind of a crowd-puller, as well as the idea of making a variety of exhibition areas available for short temporary exhibitions by artists who could not afford these otherwise.14

According to Münsterberg, “a room with only pictures, albeit set up in studio style” was “rather boring”, which is why he argued that showrooms for art should be modelled after bourgeois rooms: “The effect of a painting often relies on the surrounding atmosphere. With artful draperies, a picture can achieve a good impression, while it seems unsatisfactory when hung on a nail in the wall in an average parlour. Therefore, it may well not be in the interest of the public to be faced with an overly sophisticated exhibition of individual works. [...] The audience, therefore, has a great interest in seeing the impact of a picture on the wall of a living or dining room, over a sofa or a cupboard. From this point of view, it might be advisable to decorate a series of rooms with furniture and to distribute the pictures on the walls accordingly.”

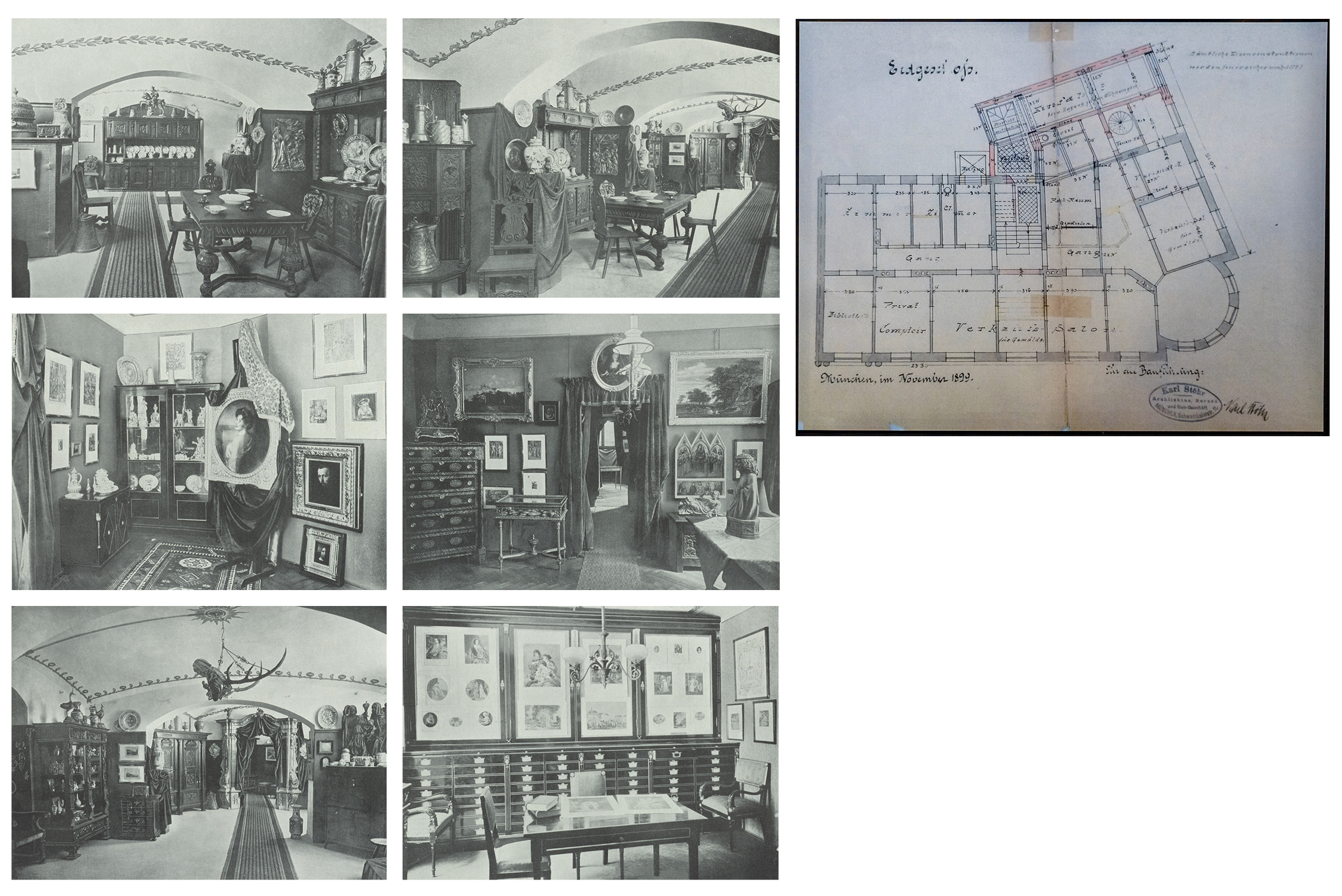

Münsterberg not only contradicts Bredt’s reform-oriented suggestion of simulating the conditions of an artist’s studio in the sales area – monochrome walls, lateral lighting15 – but with his idea of commercially-used exhibition rooms for art, he is still completely in line with tradition as implemented in Munich salerooms of auction houses and art galleries founded before 1900. When in 1900 the Munich auctioneer Hugo Helbing (1863-1938) expanded his steadily-growing art auction house and moved to a building designed by Gabriel von Seidl on Liebigstraße 21 – very close to the recently-opened Bavarian National Museum, also designed by Seidl – he not only emphasized his newly-erected “8-meter high and 320 square meter auction room with skylight”, which was said to be among the most beautiful in Europe16 and was located in an annex building finished in 1902, but he especially promoted the smaller and more intimate viewing rooms furnished in bourgeois taste where he received his clients (Fig. 1 a, b).17

In fact, comparable architectural concepts with small salons or cabinets for advising customers in a private and intimate sales atmosphere had been part of the standard repertoire and can thus be found in almost every important gallery in Munich built around 1900. Not only did they feature in the art shops specializing in Old Masters and antiques, such as those of Lehmann Bernheimer (1841-1918) and Julius Böhler (1860-1934), but also in galleries focusing on modern and contemporary art, like the Kunsthaus of Franz Josef Brakl (1854-1935). Even Heinrich Thannhauser’s (1859-1934) Moderne Galerie operated with such smaller cabinet rooms on its top floor – one of the very few private art galleries in Munich that has always been highlighted for its extremely modern exhibitions and a staging strategy at the vanguard of its time.18 But does this necessarily mean that forms of representing and staging works of art in commercial galleries got stuck in a bourgeois-conservative milieu, or were dedicated exclusively to this clientele?

Fig. 1a, views of the salerooms or cabinets of “Galerie Helbing” in Munich, around 1901 (Monatsberichte der Galerie Helbing [Special Edition], 1901); Fig. 1b, Galerie Helbing, here: plan of the ground floor (Archive of the Local building commission, Munich)

In 1893 the Architektonische Rundschau reported: “One of the most significant [...] phenomena among the recent buildings in Munich is the newly built Palace of Kommerzienrat Bernheimer, which [...] is among those buildings which seem designed to bestow an aura of the metropolis to the city on the banks of the Isar. The main objective of this building assignment was resolved by creating an enormous expanse of salerooms and offices on the ground and lower ground floor, with extensive sources of light.”19 Designed by the architect of the new Stock Exchange Building and the Palace of Justice, Friedrich von Thiersch (1852-1921), this widely acclaimed and idiosyncratic secular building was executed by his pupil Martin Dülfer (1859-1942). With its strongly accentuated neo-baroque façade and the dominant rows of shop windows, it probably appeared to contemporary critics as a showpiece and provocation at the same time, with a “nuance [...] of unprecedented audacity”.20

Lehmann Bernheimer had been born into a family of street market dealers and first opened a textile shop in Munich in 1864. Soon he began to specialize in high-quality handicrafts and oriental rugs. In 1882 he became supplier to the Bavarian royal court and in 1884 was awarded the title of commercial counsellor, a form of Royal Warrant. Three years later he bought a plot of land on today’s Lenbachplatz and erected the new building, which the Prince Regent personally opened in 1889.21

Its objective was not so much a gallery-like representation of “artworks” than the presentation of a “product range” within an organizationally and economically complex and permanent business enterprise. Bernheimer’s art palace in the style of modern Parisian warehouses with a multi-storey structure was built even before the Wertheim department store designed by Alfred Messel (1853-1909) on Leipziger Platz in Berlin, which allegedly marks the beginning of modern department store architecture in Germany. Despite historicizing elements, it presented a concise façade formulated in the spirit of “constructive modern idea”. With its close connection between business premises and private family quarters on the top floor, not only did it give “a certain architectural prestige to the Lenbachplatz”, but initiated “a new era in commercial building in Munich”.22

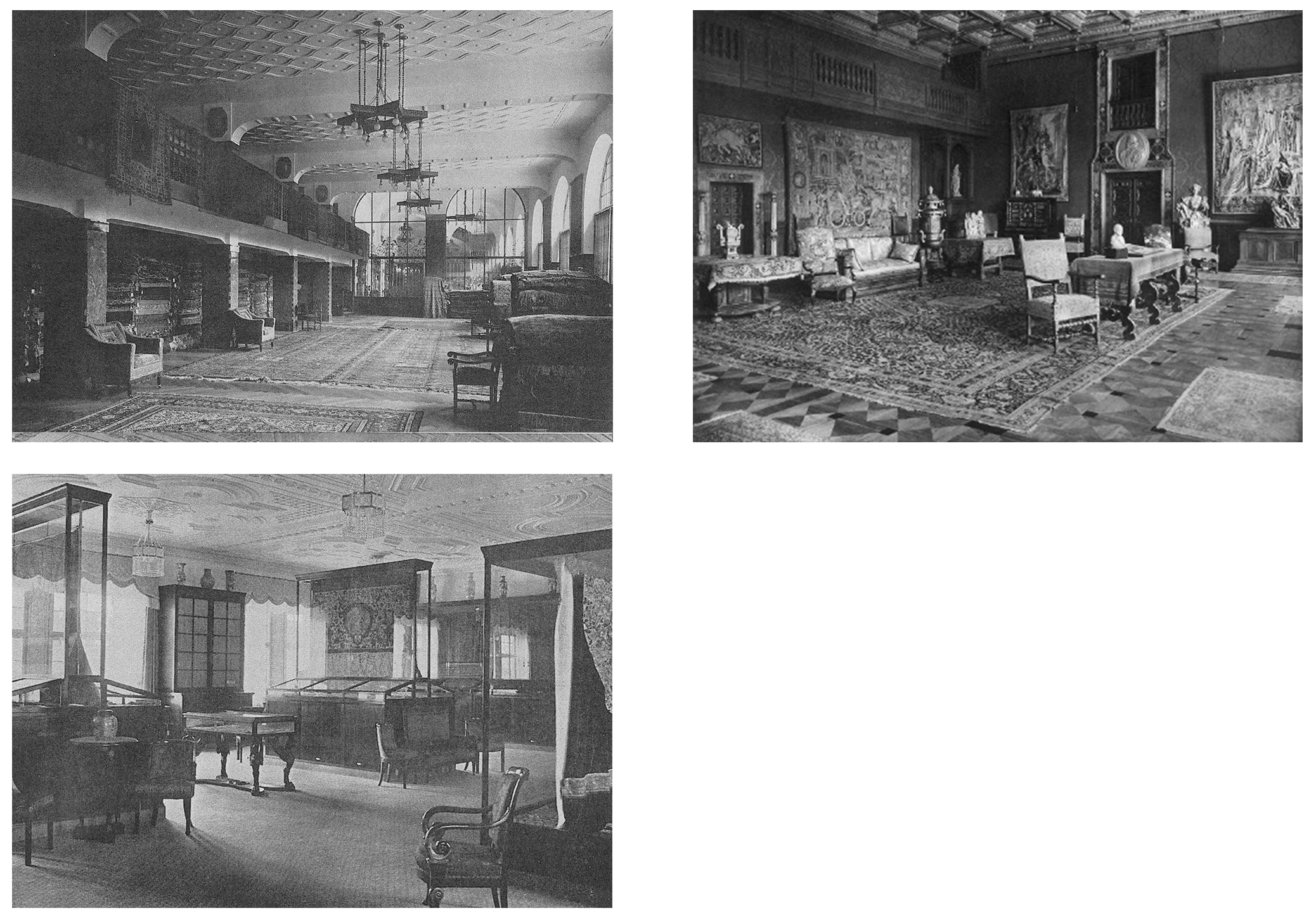

Only ten years later, the business flourished to the extent that additional warehouses had to be leased on two properties adjacent to the back of the building. On these plots in Ottostrasse, Thiersch erected an extension for 1.3 million marks in 1908, connected to the actual Palais in front by an “Italian court”. According to the Blätter für Architektur und Kunsthandwerk, this time the special challenge was “to adapt to the particular taste for which the company caters”.23 The front building was still dominated by the large hall with staircases on the ground floor, whereas the new building – whose relatively unadorned façade setting off the front of the complex – offered immense scope for the installation of individual, elongated salerooms in a “modern construction of concrete and ferroconcrete”. Each of these was modelled in a “historical style” and arranged according to product groups.24 There were carpet and lace rooms, rooms for precious eighteenth century antiquities, and a tapestry room built after a Florentine model and equipped with all manner of technical refinement, including electric winches for the tapestries and light bulbs embedded into blue ground and recessed into a paneled ceiling formerly in “dull gray color tone” (Fig. 2 a, b, c).

Fig. 2 a-c, Views of the sales rooms in the extension building of Kunsthaus Bernheimer, Ottostr, 14-16, around 1910; a) Tapestry hall, b) Gobelin hall, c) Lace room (from: Kunst und Handwerk, 1/61, 1910/1911)

The complex was further enhanced by “a suite of rooms that were kept very plain, white walls, white stuccoed ceilings [...] because it was important to gain as many walls and large wall-spaces as possible for placing furniture, and hanging tapestries and pictures.” All these walls were only lightly plastered, with the shell partially shining through which allegedly made the rooms seem pleasantly warm and made the visitor forget that he was “in the immediate vicinity of Munich’s busiest streets and squares”.25

Despite the unapologetic character of the Kunsthaus Bernheimer as a “department store”, Fritz von Ostini (1861-1927) attested that the state-of-the-art building complex with its “astonishing perfection of technology”, which allowed for the widest variety of possible uses, had surpassed the stage of a furniture or antique shop to become “an artistic institute”.26

Criticism that condemned the adaptation of department store architecture in the interests of the art market was to be expected and quickly forthcoming. In a 1906 essay in the magazine Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration Karl Widmer complained about the “shop windows’ mute art of seduction”, through which “the contents of the store are pushing more and more towards the street, which makes the shop windows expand into proper giant windows, in which entire rooms can be arranged”, whereas one would find the “least tastelessness” in shops that had nothing to do with art.27 And the Munich critic Richard Braungart (1872-1963) commented in his 1913 article Vom Kunsthandel rather disparagingly on the modern “department stores of the art industry” and satirized the “new fashion” of inducing even the “lazy and indifferent” to visit art shops by offering temporary exhibitions.28

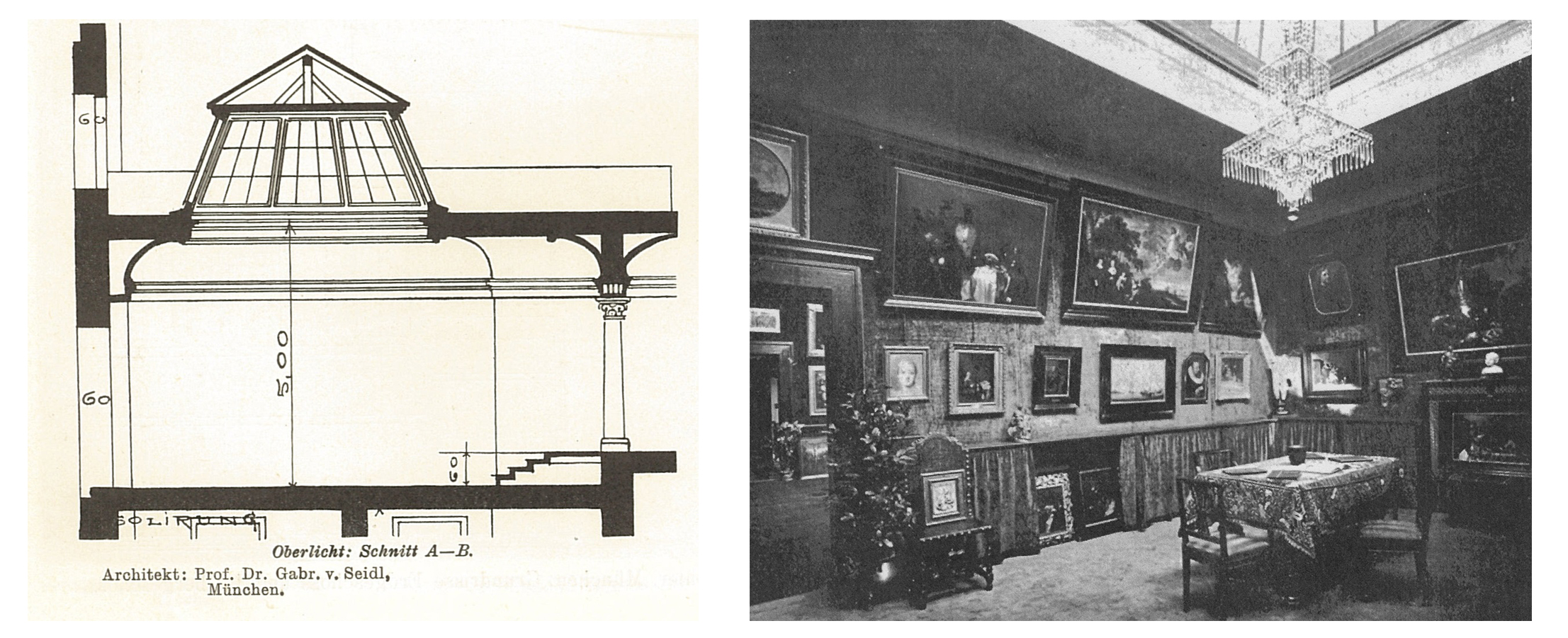

The business and residential building of Julius Böhler, art dealer to the Prussian and Bavarian courts, may not formally have been in the tradition of the department store architecture, but also followed the “new manner” in its equipment and technical construction. Its façade in the style of a northern Italian palazzo had been built in 1903 and 1904 by Gabriel von Seidl at Briennerstraße 25, very close to the Kunsthaus Bernheimer. Founded in 1880, the original premises in the company’s previous building no longer “corresponded to the importance and needs of the company, which, among other areas, cultivated the trade in old master paintings and therefore required gallery-like rooms”.29 Besides a central hall with a skylight (Fig. 3 a, b), Böhler had put special emphasis on the construction of many smaller galleries and cabinet rooms that could be used flexibly (Fig. 4 a, b). Another innovation was an additional series of smaller rooms with ceiling windows on the first floor, designed to represent the company‘s own collection and to hold temporary exhibitions. According to the Süddeutsche Bauzeitung, the most important element for the builder as well as the architect was the question of lighting, because this “was of major importance, and sidelight for the antiques seemed to be of primary importance to them. Skylight is only effective under certain conditions, that is, if its angle is not vertical but diagonal and is thus effectively dispersed into sidelight from high above. The excessive height of the rooms has usually no advantages for the objects - for obvious reasons an impression of a certain domesticity is always desirable. Out of these considerations, as well as the shape and size of the place and the need for space, the present construction project was realized.”30

Finally, Gabriel von Seidl also designed the residential and commercial building erected in 1911 for the art trade company A. S. Drey at Maximiliansplatz 7, just a few meters from the Bernheimer building complex and the Palais Böhler, which ensured the “connection of commercial life” to the “artistic spirit of the time”31 – in the most literal sense, because the property was directly connected to the New Stock Exchange Building created by Friedrich von Thiersch from 1898 to 1901.

Fig. 3 a, b, sketch and interior view of the glass-roofed hall on ground floor of the Palais Böhler (from: Süddeutsche Bauzeitung, 6/22, 1912)

Fig. 4 a, b, interior views of the “smaller” glass-roofed exhibition rooms used for changing presentations on first floor of the Palais Böhler (F. Kaufmann, Reproduction Institution, Munich, circa 1936; courtesy of Julius Böhler)

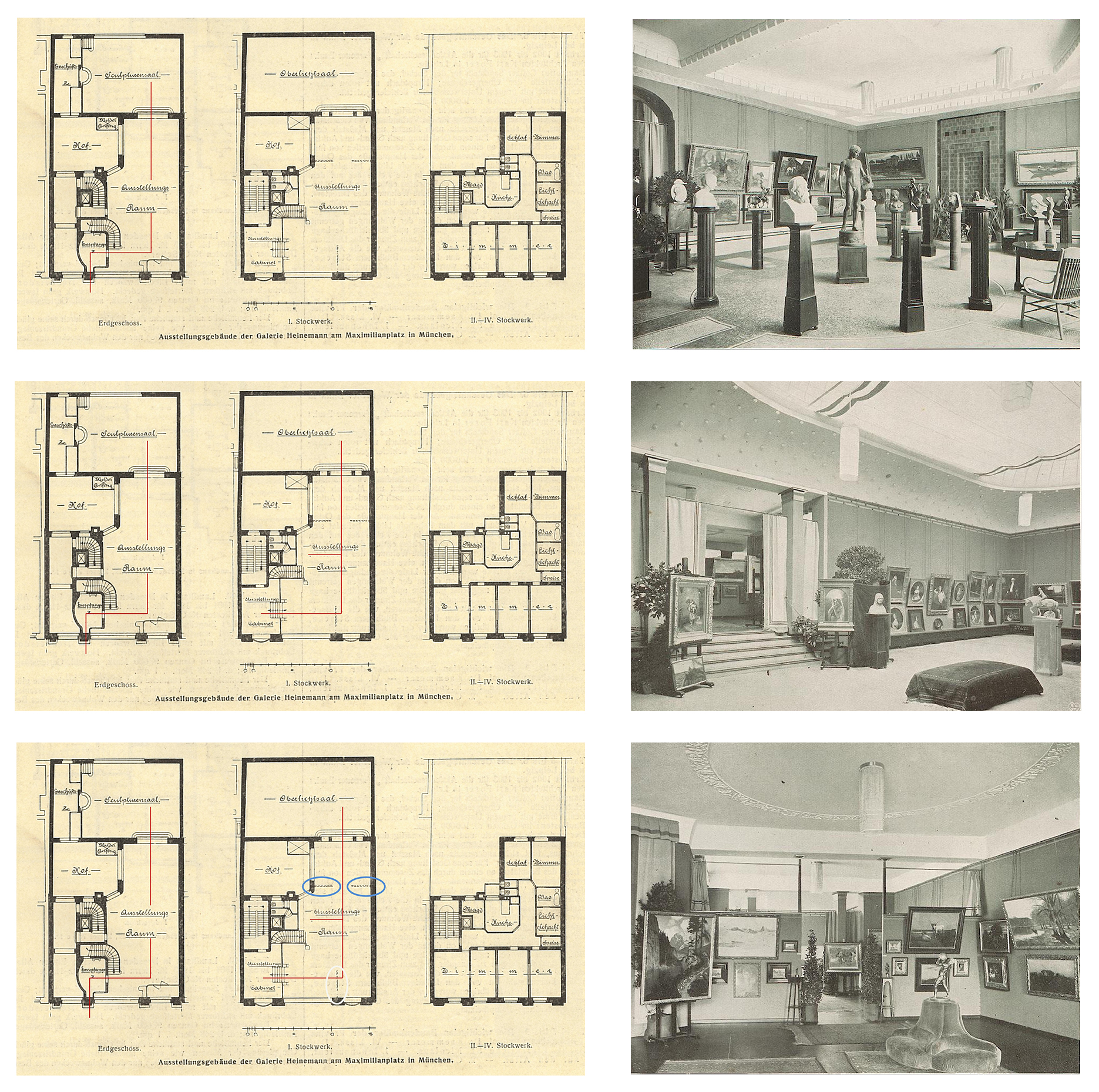

These “merchant palaces” did not single-handedly turn the area around Lenbach- or Maximiliansplatz as well as Otto- and Briennerstrasse into the center of the Munich art trade. It was also defined topographically, not far from the lively center of Munich, opposite the Künstlerhaus and within walking distance to the Munich Pinakothek, thus at an interface between consumption and culture. The most revolutionary building in this area, however, was planned by the younger brother of the architect Gabriel von Seidl, Emanuel von Seidl (1856-1919). As the Bernheimer building had already set new standards in design and technology for art dealers’ galleries, Seidl, who had created his reputation as an architect of residential villas, enforced a radical break with previous traditions in 1903 when his secular building for the Moderne Galerie D. Heinemann was finished in less than a year: “The departure of the last gloomy and sad winter days was interrupted by a festive, brilliant event. The scaffoldings on the new building on the Maximilians-Platz disappear [...], and instead a proud creation rises: The new Galerie Heinemann [...] everything presents itself meticulously rounded off, well-balanced and as if matured for a long time”, Moriz Otto Baron Lasser (1870-1916) wrote in the reform magazine Innendekoration: mein Heim, mein Stolz published by Alexander Koch (1860-1939) in 1904.32 The façade, according to Lasser’s nine-page paean, was already “the work of a modern and independently creative architect”, but nevertheless fitted perfectly into its environment. The interior design of the “great” gallery, however, seems so special precisely because “the incidence of daylight was arranged in the best possible way, so that the layout of the floor plans always adapted to the light requirements. The spatial dispositions also convey a clear, very plain and logical impression[...].” Lasser also takes the reader on a tour of the gallery: through a green reception room with red carpet and “splendid furniture” one entered the large exhibition hall with red walls. From here, the visitor turned to the sculpture hall, which was decorated in an upmarket green (Fig. 5 a, b): “A subtly arranged array of sculptures surrounds the beholder, an enchantment which dreamily envelops the viewer and takes possession of his soul. Factually, the sculpture hall presents itself as a picture in muted colours, for example the stone floor is restricted to shades of only yellow and green. Incidentally, the floors of Galerie Heinemann are made of concrete with linoleum flooring; [...] The ceilings are white as usual, also on the ground floor; the changing saturation and subtle arrangement of the electric light fixtures, confirmed Seidl’s “happy and extremely tasteful touch [...]. Thus, the ceiling has only one [...] brass ring from which light fixtures are hung [...].”

On the first floor (Fig. 5 c, d) the client once again passed green walls, leading either to the red cabinet room or the sky-lit hall: “One is surrounded by a mild flood of light [...]. This delights, as does yet another circumstance. Everywhere and in everything we can see the impact of a new time. Emanuel Seidl [...] approached his task profoundly and seriously and created a building for the modern art exhibition. The construction is never disguised [...] any theatricality, ornamentation etc are avoided. Light red and green furniture, elegant sofas, chairs, tables that display reading matter [...] and many other charming but always elegantly simple details contribute to enliven the picture of the great imposing flight of rooms.”

Fig. 5 a-f, tour through the Galerie Heinemann with ground plans and interior views of the sculpture hall on ground floor, the sky-lit hall and the large art exhibition room on first floor [author’s marks] (from: Innendekoration: mein Heim, mein Stolz, 1/7, 1904; Blätter für Architektur und Kunsthandwerk, 1/18, 1905; Architektonische Rundschau, 1/12, 1906)

In particular, Lasser emphasized the way in which, on the first floor, “large rooms are divided into smaller rooms by slender walls”, without however obstructing the view of the whole (Fig. 5 e, f). Seidl, he concludes, “breaks with tradition, and conversely gives modern man his due. [...] He [...] merges the colourful, unruly art of the palette and that of interior design into [...] an overall grand impression conceived in the mind.”

In the magazine Kunst und Handwerk the architect Hans Karl Eduard von Berlepsch-Valendas (1849-1921) also emphasized that recent developments had elevated exhibitions as such to the rank of a work of art, even to the status of a new “being”. He drew parallels to a more modern understanding of space in the private living area, especially the residential villa, and favoured the “reawakening” of a “demand for spatial education”, which meant an awareness of the fact that elements of interior equipment “are related like head and limbs to the body”.33 The same applied to an art exhibition, in which it was no longer sufficient to simply have “space to hang pictures”. Therefore, Berlepsch-Valendas appreciates the unusual in Seidl’s design, which he credits with more than just local importance: “In Paris, they may continue to pack paintings into the ‘Salon’ like herrings into a barrel. [...] Thus, if on the ground in Munich something occurs that contributes to the elevation of artistic work in general, there is no need to [...] follow famous examples.” The Galerie Heinemann showed “clearly and unequivocally the way [...] forward, [gives] clear indications [...], what needs to be done, but above all, what to refrain from. No grandiose vestibules [...], no pompous rooms with copious gilded plasterwork and faded Renaissance chair covers will henceforth have to be regarded as standard features of Munich art exhibitions, no, the dedicated, simply dignified accommodation of artistic work in rooms with appropriate lighting whose decorative features do not clamour for attention yet look refined, that should be the crux of the matter.” In the following Berlepsch-Valendas highlighted various individual elements that convinced him in the design of the rooms, particularly the different levels in height, which allowed to take different picture formats into account in the displays: deeply coffered ceilings with plenty of light fixtures, varied daylight conditions, subtle floor coverings and unpatterned, plain wall coverings. His greatest admiration, however, is reserved for Seidl‘s achievement in creating a gallery interior without the compromises entailed by the location on Lenbachplatz as the middle part in a three-part building complex. “Forcing a building that is in keeping with modern lighting conditions into the strait-jacket of historical stylistic phenomena, at all costs, is an unenviable task. What if Messel‘s ingenious work in Leipziger Strasse in Berlin, the Bazar Wertheimer, would have had to be built under similar conditions!”

While Berlepsch-Valendas thus drew a parallel to modern department store architecture, the art critic Alexander Heilmeyer instead referred to the close relationship to the museum exhibition room in the journal Kunst für Alle when he stressed that Munich had gained another “showcase”, “an art salon which satisfies the expectations of the most discerning public” and was “suitable both for the reception of individual works and for collective exhibitions”.34 In fact, in the following years the Galerie Heinemann, whose specific aim was to internationally promote the nineteenth-century painting of the so-called Munich School, was to become one of the most important exhibition institutions in Munich. Two hundred and ninety-eight exhibitions – an annual average of more than ten – were organized by the Galerie Heinemann until 1935, sometimes even in parallel. The qualitative exhibits and concepts, coherently installed by specialized curators, attracted much attention.35

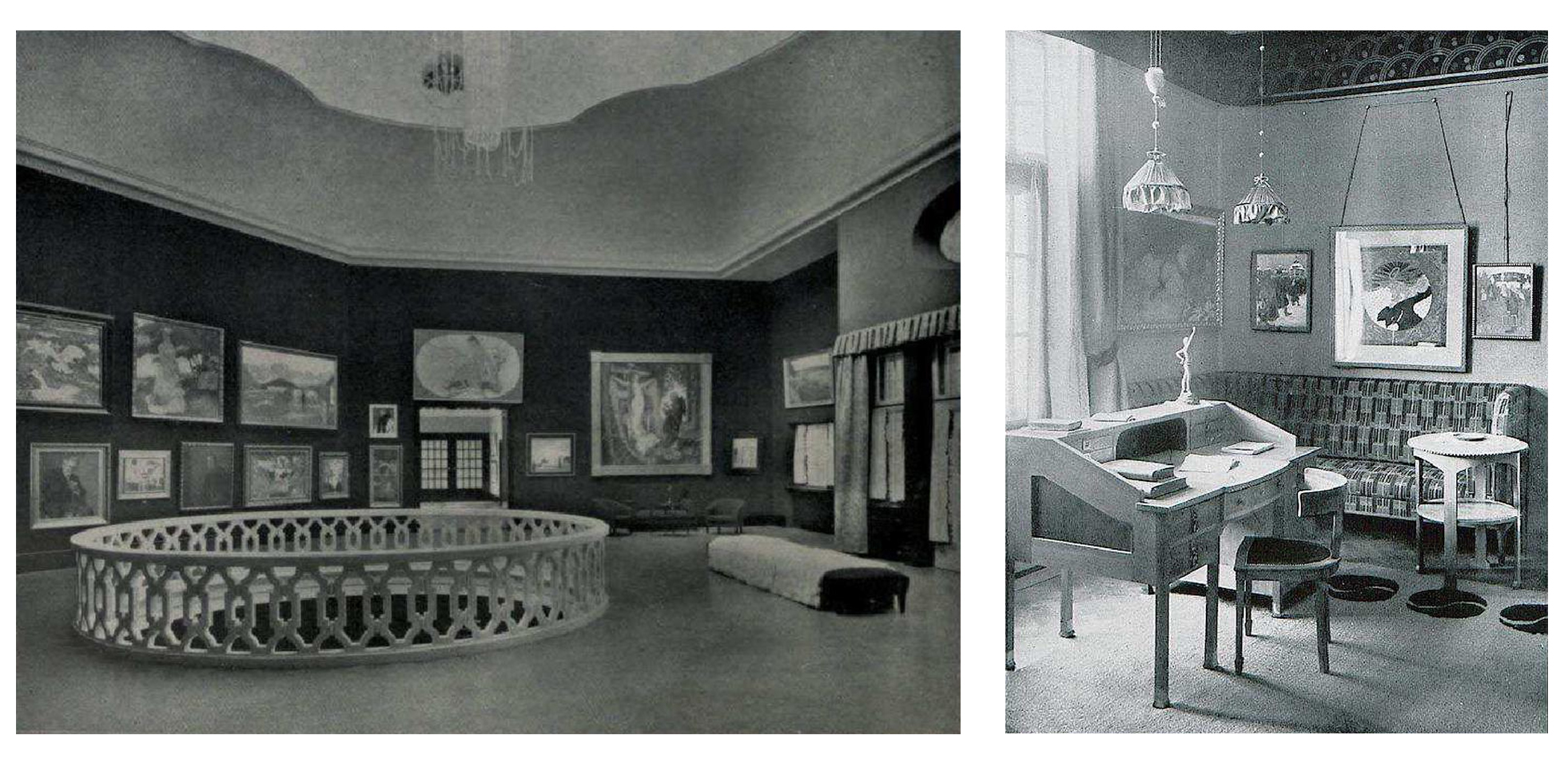

In the magazine Die Kunst, another gallery building realized by Emanuel von Seidl shortly after the Galerie Heinemann received great acclaim: “Indeed, the [art dealers] sales area with a sky-lit hall represented a considerable step forward in the art trade. Yet how much further away was [...] a private exhibition palace, as Brakl erected on Beethovenplatz!”36 When the former opera singer and art dealer Franz Joseph Brakl (1854-1935) instructed Seidl to build his Modernes Kunsthaus Brakl at Goethestraße 44, he was particularly keen to arrange the premises in a sequence that was as versatile as possible from the outset: “Mr Brakl, in the meantime, had come to the conclusion that the rule of showing a painting as if it were in the living room was after all not suitable for all artworks, but that the addition of a large hall, which allows distance effects and splendid, exhibition-like hanging, is in some cases inevitable...”.

Around a polygonal sky-lit hall covered in black fabric, several small and individually furnished cabinet rooms were arranged (fig. 6 a, b), which offered a wide variety of light fixtures and hanging conditions. Although the furnishing of these small rooms obviously mimicked the most diverse drawing room situations, the overall arrangement – above all in the hall with its ceiling windows – was even more sober than that of the Galerie Heinemann, with an almost complete absence of decorative elements: “In a gallery, the general impression of a painting is only as a passive element that takes up space; but here it becomes activated, its displacement of space has a positive value.”37

The Kunsthaus Brakl was special not only because of its unusual arrangement of the interior, but also because of its exposed location far away from the above-mentioned centre of art dealers around Munich’s Lenbachplatz: “He clearly indicates that he does not expect the public to pass by. No ostentatious monster shop window seeks to attract the attention of those passing, no company nameplate [...] appeals to the foreign visitor armed with his Baedeker [...]. But those who have once [...] found their way inside [...] will not omit to return!”38

Fig. 6 a-b, interior views of Modernes Kunsthaus Brakl, Goethestrasse 44, Munich; a) large hall with ceiling windows, b) the so-called Herrenzimmer (from: Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie u. angewandte Kunst, 28, 1913 and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 2/9, 1906)

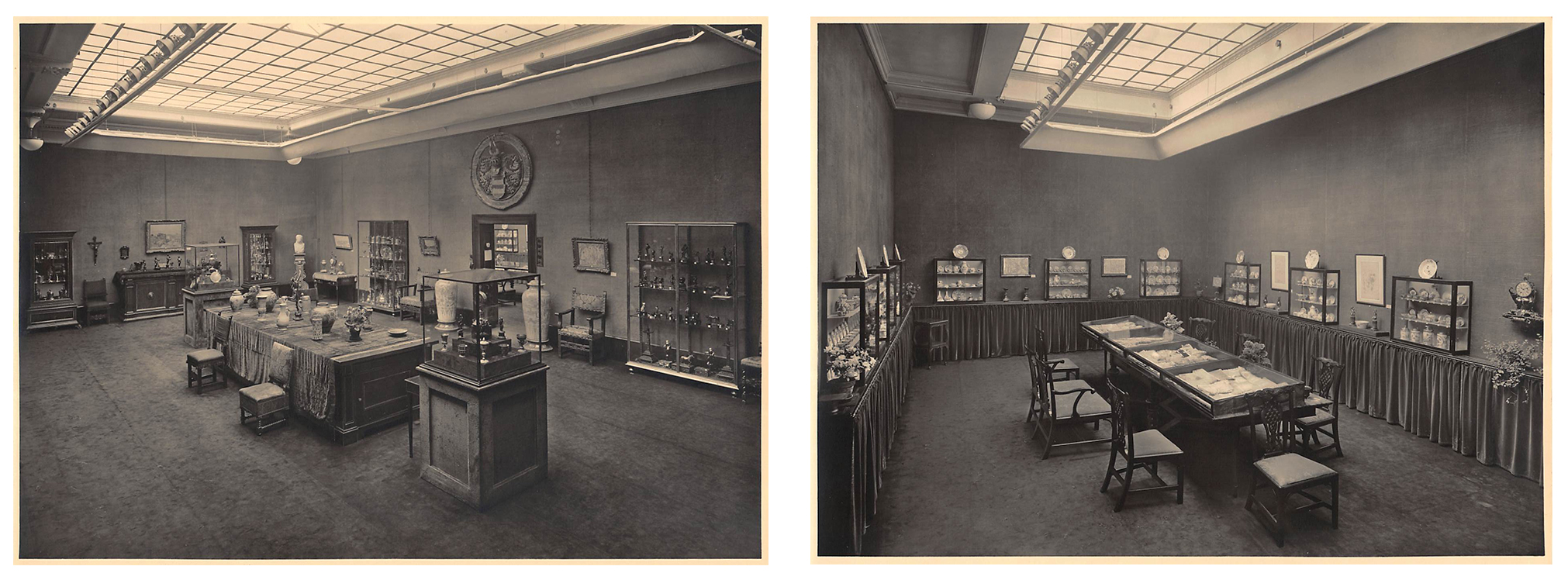

Finally, the Moderne Galerie Heinrich Thannhauser, which opened in 1909, was also able to present new exhibition halls with state-of-the-art construction technology. Its hall with ceiling windows was supposedly “able to withstand even the winter weather of Munich” and its upper cabinet rooms could only be reached through “a long ride in the lift”: “We feel transported to the picture export rooms of any global company and notice with amazement that the expectations of an international audience are taken into account as nowhere before in Munich.”39 In “avoiding the nouveau riche‘s ostentatiousness” Thannhauser, specialized in French painting, was said to have managed not to suffocate but to discretely support the pre-eminent expression of the actual work of art.40

As early as in 1906, the journal Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration had discussed the need for a reform of the art trade that could only be realized by restriction, by “selection”, by avoidance of anything “magazine-like” and liberation from the “tyranny of demand”.41 But had the reform of the art trade become obsolete in just a few years? And what impact did this have on the display space? Does this not simply counteract the function of a commercially used representation space for the sale of works of art and the idea of a universal availability of goods that still reigned supreme in impressive art dealer’s palais like Bernheimer’s? In Alarich Rooch’s 2001 dissertation, three “signifiers” – the cultural society, the bourgeois lifestyle and the consumer society – are described as being in direct relation to each other as three “staging rooms”, namely museum, villa and department store. He proved that these debates are not necessarily contradictory.42 In doing so, he also supports the thesis outlined at the beginning that the questions around a modern exhibition and spatial concept for the art trade around 1900 are inextricably linked with the ideas of the museum reform movement.

In 1913 the magazine Die Kunst noted that, “The gallery building of the art dealer presents an interesting and novel task for architects. For it has not been long that the art trade has become enthroned in its own palaces” .43 But what did this new architectural task actually entail? Was there a specific building programme, even a “fashion”, or did the architects only respond to individual and / or site-specific requirements of their private clients? Which (individual) solutions were found, and why? And how did these structural arrangements finally perform in business practice? What was the relationship between the art trade and the art or exhibition space, both before 1900 and after, both in Germany and internationally? When can forms of spatial presentation of artworks and exhibition politics in the art trade actually be described as “modern”? Is it through gradual withdrawal of product range, decoration and equipment, leading to a reduction of prestigiousness in favour of an increasing exceptionality of an artwork in its environment? Or are there other factors? These are questions that art historical research has not yet addressed.

The primary aim of this contribution was therefore not only to demonstrate that the development of the complex overall topic of “exhibition space and art trade” has been neglected by architectural history as well as art market studies. Rather, the structural development of art shops and, more generally, of commercially used spaces for the presentation of art works as a historical architectural challenge in the first place should become an integral part of our perception. It is to be expected that no uniform picture will emerge and that a story of “non-simultaneity and parallel developments” will become apparent, as Grasskamp points out in his attempt to outline a history of the “White Cube”.44 Yet a profound investigation of this subject matter can certainly capture trends and peculiarities that in turn may allow conclusions to be drawn for the history of exhibition strategy in general.

Meike Hopp is an art historian and provenance expert at the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte (ZI) in Munich.

1 Kurt Karl Eberlein, Kunsthandel und Kunstraum I: Das Kabinet, in Weltkunst, 11/18-19, (1937), 1.

2 Ibid., Kunsthandel und Kunstraum III: Der Laden, in Weltkunst, 11/26-27, (1937), 2.

3 Cf. et al. Georg Grimm, ed., Kauf- und Warenhäuser aus aller Welt: Ihre Architektur und Betriebseinrichtungen (Berlin: L. Schottlaender & Co, 1928); Louis Parnes, Bauten des Einzelhandels und ihrer Verkehrs- und Organisationsprobleme (Zürich/Leipzig: Orell Füssli, 1935); Konrad Gratz, Fritz Hierl, ed., Neue Läden. Läden – Kaufzentren – Kaufhäuser: Vol. I: Grundlagen Beispiele (München: Georg D. W. Callwey, 1957), here on p. 305-10 a few examples of the category “Books and Art”; Klaus Konrad Weber, Peter Güttler, ed., Berlin und seine Bauten, Teil VIII: Bauten für Handel und Gewerbe. Vol. A Handel (Berlin/München/Düsseldorf: Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn, 1978), under the category “shops” Güttler refers to the Berlin Kunstsalon Keller & Reiner, 179-80; Peter Gössel, Gabriele Leuthäuser, Architektur des 20. Jahrhunderts (Köln: Taschen, 1994); Helmut Frei, Tempel der Kauflust: Eine Geschichte der Warenhauskultur (Leipzig: Edition, 1997); Alarich Rooch, Zwischen Museum und Warenhaus: Ästhetisierungsprozesse und sozial-kommunikative Raumaneignungen des Bürgertums (1823-1920), in Kunibert Bering , ed. Artificium: Schriften zur Kunst und Denkmalpflege , Vol. 7 (Oberhausen: ATHENA, 2001).

4 Cf. et al. Brian O’Doherty, In der weißen Zelle: Anmerkungen zum Galerie Raum, tr. and ed. Wolfgang Kemp (Kassel: Gesamthochschul-Bibliothek, 1982); Germano Celant, Eine Visuelle Maschine: Kunstinstallation und ihre modernen Archetypen, in Saskia Bos, ed., documenta 7, Vol. 2 (Kassel: Dierich, 1982), 19-24; Ekkehard Mai, Expositionen: Geschichte und Kritik des Ausstellungswesens (München/Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1986); Bernhard Klüser, Katharina Hegewisch, eds., Die Kunst der Ausstellung: Eine Dokumentation dreißig exemplarischer Kunstausstellungen dieses Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt am Main/Leipzig: Insel Verlag, 1991); Reesa Greenberg, Bruce W. Ferguson, Sandy Nairne, eds., Thinking about Exhibitions (London/New York: Routledge, 1996); Alexis Joachimides, Die Museumsreformbewegung in Deutschland und die Entstehung des modernen Museums 1880-1940 (Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 2001); Walter Grasskamp, Die weiße Ausstellungswand: Zur Vorgeschichte des “white cube”, in Wolfgang Ullrich, Juliane Vogel, eds., Weiß (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2003), 29-63; Hubert Locher, Worte und Bilder: Visuelle und verbale Deixis im Museum und seinen Vorläufern, in Heike Gfrereis, Marcel Lepper, eds., Deixis: Vom Denken mit dem Zeigefinger (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2007), 9-37; Charlotte Klonk, Spaces of Experience: Art Gallery Interiors from 1800-2000 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Karen van den Berg, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, eds., Politik des Zeigens (München: Fink, 2010); Fritz Franz Vogel, Das Handbuch der Exponatik: Vom Ausstellen und Zeigen (Köln: Böhlau, 2012); Alexis Joachimides, De Museumhervormingsbeweging in Duitsland en het ontstaan van het moderne kunstmuseum, in Elinoor Bervelt, Debora J. Meijers, Mieke Rijnders, eds., Kabinetten, galerijen en musea: Her verzamelen en presenteren von Naturalia en Kunst van 1500 to heden (Zwolle: WBOOKS, 2013), 389-430; Katharina Hoins, Felicitas von Mallinckrodt, eds., Macht. Wissen. Teilhabe: Sammlungsinstitutionen im 21. Jahrhundert (Bielefeld: transcript, 2015).

5 Cf. et al. Walter Köhler, Lichtarchitektur: Licht und Farbe als raumgestaltende Elemente (Berlin: Bauwelt Verlag, 1956); Hugo Borger, Licht im Museum, in Ingeborg Flagge, ed., ARCHITEKTURLICHTARCHITEKTUR (Stuttgart: Karl Krämer, 1991), 213-29; Christopher Cuttle, Light for Art’s Sake: Lighting for Artworks and Museum Displays (Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier, 2007).

6 Cf. et al. Susanne Breuss, ed., Window Shopping: Eine Fotogeschichte des Schaufensters (Wien: Museum und Metroverlag, 2010); Ulrike Steierwald, Zur Ästhetik des Schaufensters. Exposition zwischen Abstraktion und Verdinglichung, in Henriette Herwig, Andrea von Hülsen-Esch, eds., Der Sturm: Literatur, Musik, Graphik und die Vernetzung in der Zeit des Expressionismus (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2015), 247-71.

7 Grasskamp, White Cube, 2003, 30, 32. Cf. Joachimides, Museumsreformbewegung, 2001, especially 156-159.

8 For a rare attempt to situate historical galleries and art shops in urban areas, cf. Stefan Pucks, Die Kunststadt Berlin 1871 – 1945: 100 Schauplätze der modernen bildenden Kunst, insbesondere der Expressionisten, im Überblick (Berlin: Wittrock, 2007). On the situation in Munich and with a strong focus on antiquarian bookshops, see Elisabeth Angermair, Jens Koch, Anton Löffelmeier, eds., Die Rosenthals: Der Aufstieg einer jüdischen Antiquarsfamilie zu Weltruhm (Wien: Böhlau, 2002), 99-115. An online exhibition on Hugo Helbing focuses exclusively on the location of “Jewish” art dealers in Munich around 1930, see Meike Hopp, Meilda Steinke, 1885-1941. Hugo Helbing – Auktionen für die Welt (URL: https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/beta/exhibit/VwKyXPJHKm3FJA?hl=en). The lack of reviews on private exhibition spaces might be due to the difficult and complex situation regarding source materials. Provenance research has increasingly explored and evaluated sources on the history of the German art trade in the twentieth century. Though questions of design and technical equipment of private exhibition spaces and the display of artworks are not the focus of interest here, provenance research has encouraged the gradual digitization of material such as auction catalogues, art magazines, and art dealers’ archival estates. While not complete, these sources provide insights into the architectural design of individual galleries, art shops, and auction houses at the turn of the twentieth century. Cf. et al. the cooperation project “German Sales”, which provides digital copies of German auction house catalogues from 1901 to 1945 - and beyond (http://artsales.uni-hd.de).

9 Grasskamp, White Cube, 2003, 33.

10 Grasskamp, White Cube, 2003, 34.

11 For the exhibition rooms of the Berlin Secession see Andrea Meyer’s introduction to this volume; DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i1.41.

12 See below the art dealerships Bernheimer, Böhler, Drey and Helbing. Although Joachimides’s exemplary study responds to forms of presentation in private collections or collector’s villas, he does not refer to any examples of commercially-used representation rooms. Joachimides, Museumsreformbewegung, 2001.

13 E. W. Bredt, Eine neue Ausstellungsweise (Atelierhaus) in München: Ein Vorschlag zum Projekt des Bayer. Kunstgewerbevereins, in Kunst und Handwerk. Zeitschr. für Kunstgewerbe u. Kunsthandwerk, 51/7 (1901), 193-200. This plan was never realized. From 1906, the new building of the “German Museum of Masterpieces of Science and Technology” was erected on Coal Island after a design by Gabriel von Seidl.

14 Oskar Münsterberg, Zum Vorschlag des Atelier-Ausstellungshauses, in Kunst und Handwerk. Zeitschr. für Kunstgewerbe u. Kunsthandwerk, 9/51 (1901), 256-57.

15 See Joachimides, Museumsreformbewegung, 2001, especially 196-98.

16 Adressbuch des deutschen Buchhandels, 93 (1931), 257.

17 For the significance of the auction house Helbing, see Meike Hopp, Kunsthandel 1938, in Eva Atlan, Raphael Gross, Julia Voss, eds., 1938: Kunst – Künstler – Politik (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2013), 151-75; Meike Hopp, Melida Steinke, „Galerie Helbing“ - Auktionen für die Welt, in Provenienz und Forschung, 01 (2016), 54-61.

18 See, for instance, Grasskamp, White Cube, 2003, 53-54; Rupert Walser, Bernhard Wittenbrink, eds., Ohne Auftrag: Zur Geschichte des Kunsthandels, 1 (München: Walser & Wittenbrink, 1989), 45-48.

19 H. E. v. B., Fr. W., Wohn- und Geschäftshaus des Herrn Kommerzienrat L. Bernheimer, Maximiliansplatz in München, in Architektonische Rundschau: Skizzenblätter aus allen Gebieten der Kunst, 1/9 (1893), 1-2, Fig. 4, 5 and 2/9 (1893), 1-2, Fig. 9, 20, 30.

20 Alexander Heilmeyer, Zum Erweiterungsbau des Hauses Bernheimer in München, in Kunst und Handwerk. Zeitschr. für Kunstgewerbe u. Kunsthandwerk, 1/61 (1910/1911), 1-7.

21 Cf. et al. Konrad O. Bernheimer, Narwalzahn und Alte Meister: Aus dem Leben einer Kunsthändler-Dynastie (Hamburg: Hoffmann und Campe, 2013); Melida Steinke, „Sonderfall Bernheimer“?: Die Enteignung des Privatbesitzes und die Übernahme der L. Bernheimer KG durch die Münchner Kunsthandels-Gesellschaft/Kameradschaft der Künstler München e.V. (München: LMU 2015, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-epub-27234-5).

22 Heilmeyer, Erweiterungsbau Bernheimer, 1910/1911, 1.

23 Der Erweiterungsbau des Geschäftshauses L. Bernheimer in München, Ottostr. 14, 15 mit 16, in Blätter für Architektur und Kunsthandwerk, 2/24 (1911), Tafel 11-13.

24 Erweiterungsbau Bernheimer, 1911; Heilmeyer, Erweiterungsbau Bernheimer, 1910/1911, 1.

25 Heilmeyer, Erweiterungsbau Bernheimer, 1910/1911, 5.

26 Fritz von Ostini, Das Haus Bernheimer in München, in Innendekoration: mein Heim, mein Stolz. Die gesamte Wohnungskunst in Bild und Wort, 1-2/3, (1919), 23-46.

27 Karl Widmer, Zur Kultur des Schaufensters, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 18 (1906), 522-23.

28 Richard Braungart, Vom Kunsthandel, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 7/7 (1913), 436-47, 447.

29 Wohn- und Geschäftshaus von Hofantiquar Julius Böhler, München, Briennerstrasse, in Süddeutsche Bauzeitung, 6/22 (1912), 41-44, 41.

30 Geschäftshaus Böhler, 1912, 42.

31 Eugen Kalkschmidt, Neue Baukunst in München, in Wasmuths Monatshefte für Baukunst, 1, (1914), 273-80, here 278.

32 Moriz Otto Baron Lasser, Neuere Bauten von Prof. Emanuel Seidl, in Innendekoration: mein Heim, mein Stolz, 1/7 (1904), 167-76.

33 Hans Karl Eduard von Berlepsch-Valendas, Der Kunstsalon Heinemann in München, in Kunst und Handwerk Zeitschr. für Kunstgewerbe u. Kunsthandwerk, 5/54 (1903/04), 140-45.

34 Alexander Heilmeyer, [o. T.], in Die Kunst für Alle: Malerei, Plastik, Graphik, Architektur, 2/19 (1903-04), 264-65.

35 See Birgit Jooss, Die Galerie Heinemann: Die Wechselvolle Geschichte einer jüdischen Kunstsammlung zwischen 1872 und 1938, in Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums (2012), 69-84; Anja Heuß, Friedrich Heinrich Zinckgraf und die “Arisierung” der Galerie Heinemann in München, in Anzeiger des Germanischen Nationalmuseums (2012), 69-84.

36 G. J. W., Brakls Kunsthaus in München, in Die Kunst. Monatshefte für freie u. angewandte Kunst, 28 (1913), 566-68. Cf. e. g. Wilhelm Michel, Ein moderner Kunstsalon in München, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 2/9 (1906), 537-44; K. Utitz, Moderne Kunsthandlung München, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 25 (1909/1910), 295-96; Kuno Mittenzwey, Brakls Kunsthaus in München, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, (1913), 151; Andrea Bambi, “Bilderfimmel und Gemälderummel”: Brakls Kunsthaus und die Künstlergruppe Scholle, in Siegfried Unterberger, Felix Billeter, Ute Strimmer, eds., Die Scholle: Eine Künstlergruppe zwischen Secession und Blauer Reiter (München: Prestel, 2007), 174-85.

37 Michel, Ein moderner Kunstsalon, 1906, 538.

38 Michel, Ein moderner Kunstsalon, 1906, 542.

39 Unknown, in Der Cicerone, 22/1 (1909), 706-7.

40 Ibid. See also W. Gebhard, Moderne Galerie-München, in Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration: Illustr. Monatshefte für moderne Malerei, Plastik, Architektur, Wohnungskunst u. künstlerisches Frauen-Arbeiten, 2/3 (1910/1911), 199-204.

41 Michel, Ein moderner Kunstsalon, 1906, 542.

42 Rooch, Zwischen Museum und Warenhaus, 2001.

43 G. J. W., Brakls Kunsthaus, 1913, 568.

44 Grasskamp, White Cube, 2003, 43, 47.