ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Bénédicte Savoy

In 1810, the French state embarked on a project to systematically register all artworks that had been confiscated since the revolution inside and outside France and declared national property. The extent of the collections of this highly heterogeneous group of objects now accumulated in the French museums since 1793 and the almost entire absence of any prior catalogues certainly presented a challenge. The result leads us to the intersection between art and economic history, where the history of European taste and the market converge, that is, in the price of European art in Paris around 1800. Although the so-called Inventaire Napoléon clearly incorporated and expanded older trends and forms for cataloguing art collections, its morphology differed distinctly from previously existing European museum inventories. The Inventaire Napoléon was accordingly ambivalent: it was an instrument of careful description, classification, and location of thousands of works of art: 4400 paintings, 1808 ancient statues and 61 vases, over 6500 drawings and other art objects registered in a total of 17 folio volumes. At the same time, it represented a listing of symbolic and financial assets in the context of national affirmation and a state treasury under great duress. The fact that these assets were also a mirror of cultural historical values makes the “price” column of the Inventaire Napoléon especially fascinating in retrospect. This catalogue was to be about art as capital.1

1 This article was first published in German in G. Swoboda, ed., Die kaiserliche Gemäldegalerie in Wien und die Anfänge des öffentlichen Kunstmuseums (Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2013), 407-418. The Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna also holds the copyright for this article.

Monsieur,

I have come to present you with the attached proposal of a protocol to proceed. Within one line, we will be able to describe any painting, no matter how beautiful, even the Transfiguration. While our work might not display picturesque beauty, it will exude administrative beauty: clarity and brevity. In this way, despite the low number of assistants available to us, we anticipate the completion of the task at hand.

Respectfully,

De Beyle1

On 27 October 1810, the young Henry Beyle, who was to become the writer Stendhal, dispatched this missive in order to encourage the general director of Musée Napoléon to take action. Since the beginning of the year, Dominique-Vivant Denon had known that he was expected post haste to take inventory of all artworks held by French castles and museums, as stipulated by a law passed by the Senate on 10 January. However, since then nothing at all had taken place. Denon had pointed out the overwhelming complexity of the task, while his contact in the government, Intendant-General Pierre Daru, insisted that the task be accomplished with all speed.2 At issue was the systematic registration of all the artworks that had been confiscated since the revolution inside and outside France and declared national property; in other words, the unified structuring of a highly heterogeneous ensemble of objects of the most diverse provenance in various genres and media. This presented an enormous challenge. While cataloguing inventories of the holdings of collections and galleries were part of a long European tradition and led to an elaborate taxonomy of “museum inventories” in the eighteenth century, the extent of the collections now accumulated in the French museums since 1793 and the almost entire absence of any prior catalogues presented a special set of circumstances. Even greater difficulty was generated by the new administrative spirit in the service of which this cataloguing was to take place: statistical thought and action, the virtually complete collection of data from all realms of society and from all over the country were central to Napoleonic policy. Already under Napoleon’s Consulate in 1801, the systematic and regular collection of data by the state had begun on the level of the prefecture.3 Now, “national” works of art were to be registered as if in a census. But this did not correspond to the museum director’s understanding of his scholarly mission: Denon himself claimed to be working on an inventory of his own, a catalogue raisonné. But even the museum as a temple of beauty was forced to submit to the administrative logic of the centralized state. Precision and objectivity, comparability and completeness - the inventory to be completed was an early form of the same modern statistics, which in the 19th century would become the “most important instrument for the continuous self-monitoring of societies” (Osterhammel),4 and now applied to artworks. Intellectual and aesthetic “picturesque beauty” had to bow to administrative precision, with wonderful, as yet hardly investigated consequences for art history. One of these consequences leads us to the intersection between art and economic history, the history of European taste and the market: the price of European art in Paris around 1800.

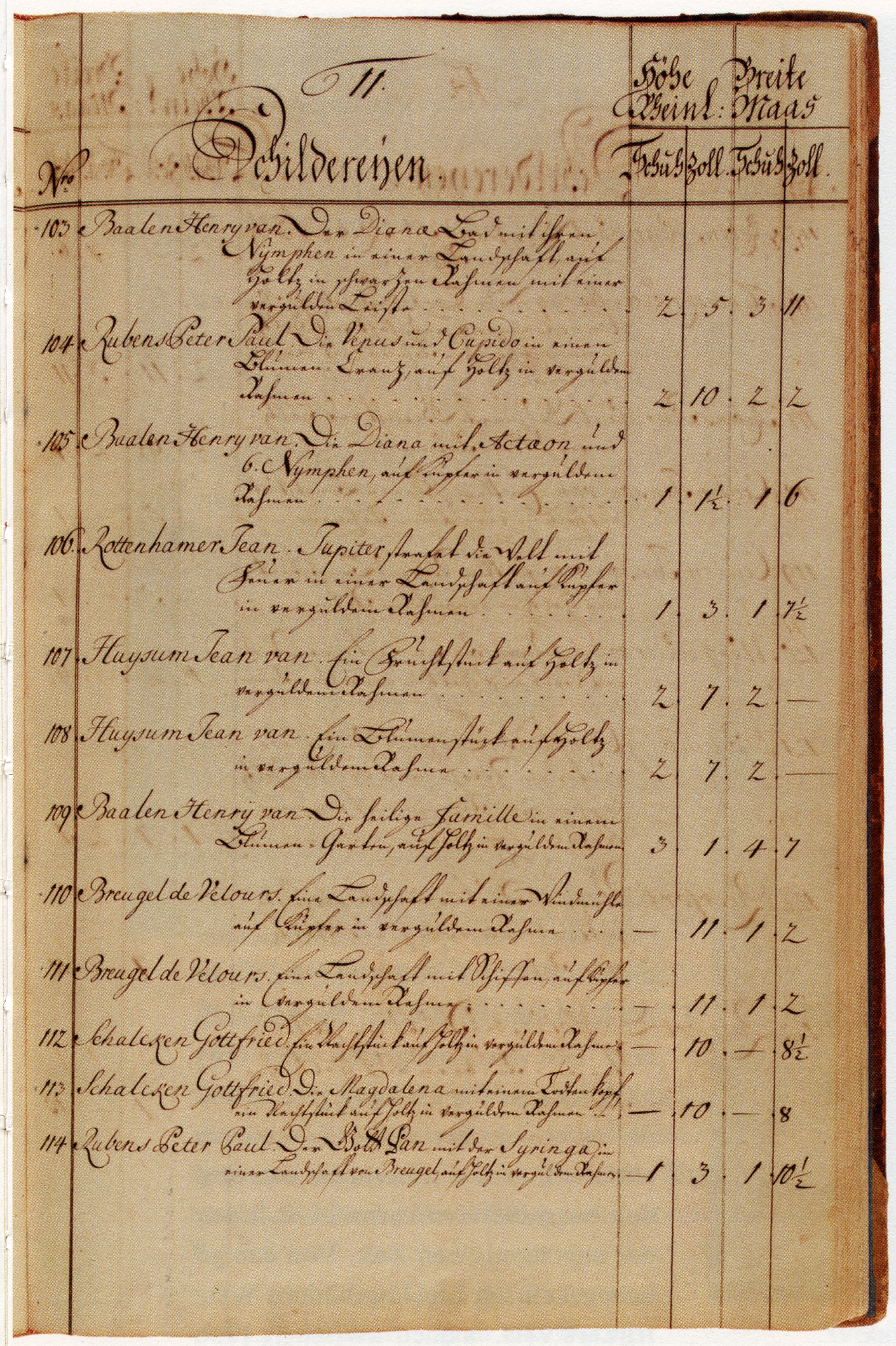

Fig. 1: Administrative Beauty. A page from the Inventaire Napoléon; Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, Inventaire général du musée Napoléon 1810, peintures t. I, fol. 108

In the beginning, there was only the chilly blankness of the tabular grid.5 Nine columns, printed on both sides of heavy paper, were to serve as a matrix for registering the state’s art holdings (fig. 1). This included first and foremost the collection of the Musée Napoléon, the successor institution to the Musée central des Arts founded in 1793. From October to December 1810, Denon, his superior Daru, and his cousin, Henri Beyle, who was hired as the driver of the enterprise, discussed the number and title of the categories to be included at some length in their correspondence. Ultimately, a model was agreed upon that seemed appropriate for all art objects: paintings as well as ancient sculpture or vases, drawings and cameos, as well as decorative artworks. Each page of the inventory was to begin on the left with the column “number,” followed by the columns “name of the master,” “title of the subject matter,” “dimensions (height and length),” “origin,” “estimated price of the object,” “estimated price of the frame/pedestal,” “current location,” and, on the far right, “notes.” None of the envisaged columns was wider than seven centimetres. Since both the column titles and the dividing vertical lines were preprinted on all pages of the register, there was to be no room for potential deviation. There was not even any space provided for descriptions of the medium or the object’s condition, as was customary in collection inventories of the time. That is telling: although the catalogue général (today and in the following: Inventaire Napoléon) clearly incorporated and expanded older trends and forms for cataloguing art collections, its morphology differed distinctly from previously existing European museum inventories. Around 1810, its administrative beauty revealed things that until then had remained irrelevant, concealed, or self-evident. Other aspects, however, now became hidden.

First of all, there is the category “origin.” In 1810, the holdings at the Musée Napoléon included works of the most varied provenance: the former Royal collection, aristocratic and church collections from all over the republic that had been confiscated from 1791 onwards, and the so-called conquêtes artistiques made by the French Republic and later the French Empire from 1794 in the Netherlands, Italy, the German-speaking world, and Spain. Remarkably, the category “origin” became the subject of a not merely philological debate between the museum expert Denon and the economic official Daru. Denon first suggested including a column entitled “provenance.” In response, Daru requested changing the title of this column to “origin,” and to add another column with the cumbersome title “how the works were acquired.”6 When we take a look at the completed pages of the Inventaire Napoléon (fig. 2), it becomes obvious that the concept of origin was not to encompass an art historical category - neither the traditional geographic attribution of artworks as “schools,” nor a chronological listing of an object’s owner changes over the centuries. There are entries such as “anc. col. de la Couronne” (former Royal Collection), “Conquête 1806”, “Palais Pitti à Florence,” “Conquête 1809.” The heading “Origin” thus documented the ownership directly before the objects’ nationalization respectively military confiscation by France, and registered them as “displaced objects” as a consequence of the policies of appropriation and nationalization in the French Republic and later Empire. “Conquête 1806” indicates locations such as Berlin, Potsdam, Kassel, Schwerin, Braunschweig, Danzig, and Warsaw, while “Conquête 1809” refers to Vienna. It is worth noting that almost no eighteenth century European museum inventory had listed the origins of its works - the inventories of the portrait galleries in Kassel (fig.3) and Dresden (fig.4) provide no information about the previous owner of the works, no matter how prominent they might have been. Clearly, the “catalogue général” continued and formalized a different practice from the one that had been prevalent across Europe before. The new and fervently practiced creation of lists as well as registers and protocols of confiscation, that in France accompanied the transfer of mobile goods to new state ownership as of 1791, while naturally operating primarily with the category of “origins”, was clearly of crucial importance.7 But equally important was the new post-revolutionary understanding of art possession, which in both theory and practice stylized the appropriation and integration of widely dispersed collections as a great achievement of civilization. By capturing the dynamic, indeed chaotic process of this fusion in a sober, objectivized, administrative column labeled “origin,” the Inventaire Napoléon contributed to the affirmation of the state’s power. It goes without saying that the idea of translatio imperii resonates between the lines of the Inventaire Napoléon, the transfer of culture, knowledge, and domination from old world empires to the new. Immense symbolic capital was generated not just through the real accumulation of artworks in France, but also through the concentrated, statistical registration of their prominent prior owners and locations. In this context, it is entirely consistent that adjacent to the column “origin”, not one but two columns were provided for the price of the artwork. This catalogue was to be about art as capital.8

Fig. 2: Inventaire Napoléon. Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, Inventaire général du musée Napoléon 1810, peintures t. II, fol. 281

Unlike the column “origin,” there seems to have been a consensus among those behind the Inventaire Napoléon about including the column “price”: while the first model suggested by Beyle did not include such a rubric, it appeared immediately in Denon’s response and was also adopted by Daru.9 The sums to be entered were to be provided only in francs, which, in light of Europe’s range of currency and the remaining competition between several different currencies inside France itself around 1810, can be considered a blessing. The same is true for the fact that the dimensions of all artworks were given in centimeters and metres instead of the respective units of measurement in their countries of origin, from the Tuscan elle to the Prussian Fuß. The column “price” was divided in two, one for the artwork itself, one for the frame/pedestal. From a current perspective, this attention to the frame and/or pedestal might seem surprising. But in the time around 1800 there was nothing new about this: already the Catalogue des tableaux du Roi déposés au Louvre from 178510 and the Etat actuel des tableaux de la surintendance11 from 1788, for example, mentioned the age and condition of the “bordures.” But what was entirely new was stipulating a concrete value for the artworks in museum possession. Neither the catalogues of the French ancien régime nor comparable inventories of other public collections in Europe seem to have operated with this category before 1810. And why should they have? Insurance value, as we know it today, played no role at all for museums in the early 19th century; and the practice of temporary art exhibitions, with the mobility and endangerment of artworks that it involves, did not yet exist.12 And it would have been difficult for someone to conceive of the idea of having works appraised for resale in 1810, for the principle of the perpetuity of large royal or national collections had become established all over Europe.13 While during the years of confiscation 1793/94 numerous French collections were appraised before being nationalized (fig. 6),14 and now and then printed museum catalogues bragged about the high sums necessary for the acquisition of a work, the price of art seems to have played no role at all behind the scenes, that is in the internal registers of museums inside and outside France around 1800. Once the works reached a public collection, they seemed to be sheltered from the market “in perpetuity”15. So we need to raise the question once more: why the column “price” in the Inventaire Napoléon?

Fig. 3: Inventory catalogue, Gemäldegalerie Kassel 1749, Staatliche Museen Kassel, Archiv

We can only hypothesize here. Surely the dramatic financial crisis beginning in 1810 led the French government to want to obtain an overview of state art possessions. With annual expenditures of over 500 million francs for the army (1811: 460 million, 1812: 520 million, 1813: 585 million)16 it is only understandable that the Senate and the Intendant General wanted to be informed about all forms of state property. From the perspective of museum director Denon, who after all seems to have suggested the price column himself, high sums with many zeros had always been a good way of demonstrating the importance of his museum or the necessity of certain purchases, renovations and other building projects to his superiors, who did not always share his interest in art - first and foremost the emperor himself. There are many examples of this, one of which has fortunately survived. It is a letter that Denon sent to Napoleon at the end of 1806 to convince him to partially move Dresden’s picture gallery to Paris. He wrote:

Fig. 4: Inventory list, Gemäldegalerie Dresden, handwritten catalogue entry for the Sistine Madonna in the Royal Inventory, 1754, In: Matthias Oestereich, Inventarium von der Königlichen Bilder-Gallerie zu Dresßden, gefertigt: Mens: Julij & August: 1754, fol. 5, No. 31. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Altregistratur, Inv.-No. 359

The monetary value, that will never be entirely paid in the contracts, could be replaced with several pieces that would take on actual value, for they would find their way entirely into the treasure of your fame and remain there forever. Even if your Majesty were only to demand a few objects, in any case great value would be accumulated. A single painting by Raphael from the Dresden collection was paid for by King August with 9000 Louis, for your Majesty this value has doubled. Correggio‘s Night has at least the same price: two other Correggios and a Holbein are of the same calibre. The latter painter is lacking in your museum. It would not be pillage if I suggested that Your Majesty demand four or six paintings from the collection.17

Museum practice and economy, autonomy of the arts and economic thinking: Denon’s strategic interest in placing a monetary value on the (war) treasures kept in his museum can hardly be clearer. The Inventaire Napoléon compiled under his direction was accordingly ambivalent: on the one hand, it was an instrument of careful description, classification, and location of thousands of works of art; on the other it represented a listing of symbolic and financial assets in the context of national affirmation and a state treasury under great duress. The fact that these assets were at the same time a mirror of cultural historical values makes the “price” column of the Inventaire Napoléon especially fascinating in retrospect.

But let’s take a step back: what exactly did the work on the Inventaire Napoléon comprise in late 1810? Who was responsible for counting the 4400 paintings, 1808 ancient statues and 61 vases, over 6500 drawings and other art objects registered in a total of seventeen folio volumes? And above all else, who was responsible for the valuation of works that until being transported to Paris in many cases had never changed ownership or had no history of ever having been on the market? How should such prices be determined? Who should decide how much works by Raphael, Dürer, Rembrandt, and Titian, or Laocoön and His Sons were worth in francs? Fortunately the correspondence of general director Denon provides some information about each of these questions.18 When reading the correspondence, the speed at which the inventory was compiled despite limited staff becomes apparent, as well as the synergies that had to be generated between the market and the museum in order to adequately value these “invaluable masterpieces,” as they were so often called. Significantly, both projects - the description, measurements, and location of the works on the one hand and their valuation on the other - did not take place in parallel, but successively. Two separate teams were at work under Denon’s direction. At first, the two conservators Ennio Quirino Visconti (for antiquities) and Jean-Baptiste Morel d’Arleu (for drawings), most likely supported by the museum secretary Athanase Lavallée (for paintings) and two to three assistants were working in the museum; only after finishing their work in October 1813 did Denon summon a second group of experts that was to be exclusively responsible for valuing the works. The invitation Denon sent out is worth citing at length, for it provides a precise insight into the general director’s pragmatic approach. He wrote the following to each of them on 11 October 1813:

Monsieur,

The general inventory of all the paintings, drawings, statues, and other precious objects has now been completed. The issue now is to assign a price to each described object. For such an important undertaking, I do not want to rely solely on my own knowledge and that of the curators in our institution, and so I thought that you might support us with your expertise. I therefore invite you, sir, to come next Wednesday, October 13 to the museum to take up work with several counterparts also invited by me. Through our contradictory discussions on the price of the objects, their real value (la valeur réelle) will be established.19

What a wonderful letter! Despite all the uncertainty it resonates with Denon’s confidence that a “real value” - perhaps in contrast to a “felt value” - could be established for the art treasures in the Musée Napoléon, and tellingly through “contradictory discussions” on site. Generating objectivity by confronting subjectivities - it will be hard to find a clearer avowal of the irrational character of price determination in the realm of art.

Fig. 5: Confiscation lists and logs AMN. Paris, AMN, 1 DD 7, Objets d’arts et de sciences transportés au Museum 1793–1796, fol. 21

Who then were the three attendees? They were all, as Denon called them in later letters, Parisian “négociants en objets d’art”20 or “artistes-négociants”:21 Pierre-Joseph Lafontaine (1758–1835), Ferreol de Bonnemaison (1766–1827) and Guillaume-Jean Constantin (1755–1816). The Belgian-born Lafontaine, who initially worked as a painter, set up as an art dealer in Paris after the revolution and quickly achieved fame and fortune through sensational purchases and sales of primarily Dutch paintings - for example, Rembrandt’s The Woman Taken in Adultery, discovered at a Dutch auction in 1803 and sold several years later in London.22 The painter, restorer, art dealer, and collector Bonnemaison23 emigrated to London after the outbreak of the revolution, where among other activities he dealt in art and returned to Paris in 1796, where he continued to work as an art dealer and restorer. By around 1810, Bonnemaison was obviously considered a Raphael expert, for three years after his appointment as Denon’s general cataloguer he was named chief restorer of the Louvre (renamed Musée royal) where he had five Raphael paintings restored, that were about to be restituted to their legitimate owner, the King of Spain. On this occasion, Bonnemaison made prints based on these Raphael paintings, publishing them with some success.24 Finally, the art dealer Constantin had been curator of the painting collection of Empress Josephine at Château de Malmaison since 1807, and in this capacity valued and purchased several high quality works.25

On 13 October 1813, the commission began its work together with Denon, museum secretary Athanase Lavallée, and antiquity curator Visconti.26 A week later, Denon announced to the general director that the group had “already met several times” and that the valuation of all paintings from the Grande Galerie was as good as complete.27 The result was impressive: thousands of figures now filled the “price” column of the Inventaire Napoléon, from 1.5 million francs down to one franc. Everything that European art history brought forth from antiquity to Jacques-Louis David and collected at the Musée Napoléon now not only had a value, but also a price.28 If we take a closer look at the table it becomes apparent that in many cases these prices were and could only be pure abstraction.

Fig. 6: Appraisal of confiscated collections AMN, 1 DD 4. Paris, AMN, 1 DD 4, Inventaire des tableaux de la surintendance à Versailles 1794. Objets d’arts et de sciences transportés au Museum 1794, fol. 17–18

What could a marble group be worth that, as even Pliny the Elder already noted, “is preferable to any other work of painting or sculpture”29? Or the final picture by the painter from Urbino, who was considered divine and died before his time? Since their discovery respectively creation in the years 1506 and 1520, neither Laocoön and His Sons nor Raphael’s Transfiguration, nor many of the works from the Musée Napoléon taken from Italian and Netherlandish collections had ever been on the art market: they had never changed ownership and only rarely, if ever, changed their location. For such works, it was impossible to establish a “real” price, based on whatever documentation available. Across all of Europe, by the eighteenth century at the latest they had developed independently of the market to become icons of aesthetic and art historical discourse, objects where the new religion of art had materialized over the course of the centuries. If they had a value, it was of a cultural, or rather cult-like kind - but surely not, at least not primarily, of an economic nature. What prices could Denon and his advisors come up with for their valuations?

For Laocoön and His Sons: 1,500,000 Francs.

For The Transfiguration: the same price.

In 1813, these were sums that would have exceeded the imagination of many: 7.5 times the yearly apanage of a duke30 or the value of 10 good houses in a wealthy bourgeois Paris neighborhood.31 A museum guard earned 100 francs a year at the time.32 Having established such a high benchmark, the experts used the entire scale of prices to appraise the remaining ancient articles, paintings, and drawings in the museum’s holdings with very few exceptions. 1.5 million francs was a price achieved by no other work in the collection. The next level of 1 million francs was only reached by two Italian paintings: Correggio’s St. Jerome from Parma and Paolo Veronese’s Wedding at Cana from Venice.33 Only six paintings were valued down to the next level of 500,000 francs, including, not surprisingly, three by Raphael: the Madonna di Foligno (800,000), the Holy Family (600,000) and St Cecilia (500,000); in addition to these paintings, Giulio Romano’s Stoning of St Stephen (700,000), Titian’s Martyrdom of St Peter (500,000) and Domenichino’s Communion of St Jerome (500,000).34 For the first time, a non-Italian painting appears in this price category: Rubens’s Descent from the Cross from Antwerp (600,000).35 The second most expensive Netherlandish painting was a large animal scene by Paulus Potter from the collection of The Hague’s Stadthouder (430,000).36

Two dozen Italian and Netherlandish paintings were assigned values down to the next level of 100,000 francs. Here, there are also the first paintings from the French school, works by Eustache Lesueur and Charles Lebrun (250,000 and 200,000 francs) followed by four pictures by Nicolas Poussin valued at 150,000 francs and two by Claude Lorrain for 100,000 francs.37 A handful of Netherlandish masters were also assigned prices at this level, including Rubens, as well as Van Dyck with the highest price of 150,000 for the Mourning of Christ from Antwerp and Gerard Dou with the Dropsical Woman from the French Royal Collection (120,000). At this price level, only Van Eyck represents the earlier Netherlandish school, with the central panel of the Ghent Altarpiece (100,000).38 Below 100,000 francs, the ranking becomes more convoluted: surprisingly, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa was valued at “only” 90,000 francs,39 Rembrandt’s top values reach 60,000 francs for the painting Jacob Blesses the Sons of Joseph from Kassel, highly praised in Paris,40 and there are two works by Mantegna, also valued at 60,000 francs.41 For Murillo’s most expensive painting, The Holy Family, a price of 48,000 was registered.42 In the next bracket below, there are numerous Italian pictures as well as a compact group of Netherlandish landscape or genre painters like Berchem, Both, Ostade, Teniers oder Metsu (top valuations around 30-40,000 francs).43 The most expensive Early German paintings were valued at prices between 10,000 and 15,000 francs: Altdorfer’s The Battle of Alexander at Issus from Munich (15,000), Holbein’s Portrait of Nicolaus Kratzer from the French Royal Collection (10,000) and an Adoration of the Magi from Savona attributed to Dürer (10,000).44 Despite the great demonstrable popularity that it enjoyed among the Paris audience, Cranach’s Fountain of Youth from Berlin was only valued at 3,000 francs.45 The same is true of Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera from the French Royal Collection.46 Chardin’s work did not exceed 1000 francs.47 The lowest prices were assigned to copies of well-known masters or paintings that could not be attributed to any particular artist.

This much too brief overview would of course need to be expanded, especially for an analysis of prices set in accordance with picture size and genre. But a sketchy survey still allows for several conclusions. In 1813, Raphael had entirely surpassed Correggio, as can already be seen in contemporary art criticism. The Raphael cult in Europe around 1800 that Ernst Osterkamp described in such detail, is directly reflected in the Inventaire Napoléon.48 The level of Raphael’s prices directly reflects his position in the artistic and aesthetic firmament of the period. Even the gap between Raphael and the nearest prices below seems to indicate that the “divino” was (by then) beyond competition. This resulted not least from the wide spectrum of works gathered in the collection at the Musée Napoléon. While in 1777 an anonymous traveler (Martin Sherlock) would note pedantically:

At the Vatican, one learns to admire Raphael’s masterpieces; in Dresden, one can learn to appreciate Correggio’s paintings. Raphael is almost universally recognized as the monarch of painting. I would prefer a consular form of government; I wish he had had Correggio as a colleague. I know, that all the semi-connoisseurs will be against me, and I want to tell them the reason for this: either they haven’t seen the most beautiful works by this master, or they have only looked at them fleetingly. His best works are in Parma and Dresden, and these are two cities a traveler only visits in passing. Perhaps the visitor spends three mornings in the gallery: he wants so see everything and, naturally, he sees nothing at all. This is how he approaches Parma, and behold, he has arrived in Rome.49

... and thirty years later, in Paris. By the time when several masterpieces by Correggio and almost Raphael’s entire oeuvre were assembled at the Musée Napoléon, the discussion, if we believe the numbers, seems to have become definitively obsolete. Raphael clearly occupied first place, followed by the Italian school and far ahead of the Netherlands. Only Rubens and the painter Paulus Potter, celebrated for his bovine subjects, could compete with the best Italians on price. Only detailed regional studies could clarify whether this assessment was particularly French or on the contrary reflected European period taste in general, which is quite likely. The aforementioned “hit list” certainly demonstrates an emerging interest in Rembrandt, whose prices separated him from other genre painters such as Metsu, Teniers, or Ostade which were collected around Europe and well represented in many princely collections. In other words: with their “contradictory discussions” before the originals of the Musée Napoléon, the art dealers invited by Denon had not only translated general taste trends to prices. They also surely helped to set trends: this is especially clear for Van Eyck and the early German painters, who at this time had no market value to speak of due to being located in churches and convents and unavailable for the market. By valuing the centerpiece of the Ghent Altarpiece at 100,000 Francs, above Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, works by Altdorfer, Dürer, and Holbein were priced at a level otherwise only assigned to good Rubens portraits, which also created an economic benchmark system for these artists.

How does the story continue? As is well known, in 1814 and 1815 the collection at the Musée Napoléon was dismantled by the victorious allies. The copy of the general inventory which had remained at the Louvre was in extensive use at the time, for it facilitated the quick and secure identification of reclaimed works and their legitimate owners. After the emptying of the Louvre, the new museum officials who had replaced Denon after his resignation began to catalogue the remaining holdings in an Inventaire des tableaux du Roi (1816). Interestingly, most of the categories used for the Inventaire Napoléon were retained, including the column “price.” The column “origin” however was eliminated, while information about the medium was added. The prices in this inventory did not change, clearly they were taken from the Inventaire Napoléon. It was only with the next Inventaire général des Musées Royaux from the year 1824, that had a similar structure and once again included origin, that the prices changed: Raphael’s prices rose dramatically (reflecting the general developments in Europe) so that, for example, the value of St. Michael doubled from 100,000 francs (in 1813 and 1816) to 200,000 francs at that point.50 At the same time, looking at Leonardo’s Mona Lisa we find that it lost value and ended up at 80,000 francs,51 and the same applied to Rembrandt as well, whose Tobias for example was only worth half of what it had been in 1813, that is to say 30,000 francs.52 Had the Louvre inventories continued their price column after 1824, the history of economic fluctuation and of rises and falls in prices could have been traced brilliantly for the entire nineteenth century. Unfortunately, even by 1832 the directorship had abandoned such valuations; the price of the art is no longer recorded in the Inventaire général des Musées royaux completed that year. In the history of museum catalogues, the Inventaire Napoléon and its successors from 1816 and 1824 remained a historical exception.

From today’s perspective, this unique catalogue can be read in two ways: as an impressive compendium of national art ownership in France under Napoleon: but also, if we consider the column “origin”, as an atlas of Europe’s art geography against the backdrop of the great transformations of the French Revolution. It offers a source unrivalled in precision for an autopsy of the mighty European body of art at the moment of its greatest concentration in Paris.

There is every reason to assume that in Napoleonic France generally more statistical knowledge was produced than could ever be used scientifically or administratively,53 but in hindsight it is fortuitous that almost all the paintings, drawings, and ancient artifacts were valued (each one in francs!). It opens up the most wonderful opportunity for subsequent research on art as capital on the one hand and taste as a historical category on the other. In other words: not only Pierre Bourdieu would have enjoyed the column “price” of the Inventaire Napoléon, for it perfectly embodies his idea of an economy of symbolic goods in the museum. It is a mine of information for anybody attempting the difficult task of tracking the history of European taste in art around 1800, or more generally, the historical contingency of taste, based on complex and widespread indicators such as museum catalogues, art books, press reports, replica casts, reproduction prints, and lists of copyists.

(Translation: Brian Currid)

Bénédicte Savoy has been professor of art history at the Institute of Art History at Technische Universität Berlin, Germany since 2003.

1 Stendhal to Denon, 27 October 1810, AMN Z 3 1810, quoted from: Marianne Hamiaux/Jean-Luc Martinez, De l’inventaire N à l’inventaire MR: le département des Antiques, in Daniela Gallo, ed., Les vies de Dominique-Vivant Denon, 2 vols (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2001), 434-435, and ill. 441.

2 For more on the structure of Inventaire Napoléon and its origins, see Lucie Chamson Mazauric, L’inventaire du Musée Napoléon aux archives du Louvre, in Archives de l’art français, (1950–1957), 335–339; Hamiaux/Martinez, De l’inventaire N à l’inventaire MR, 431–460; see also the introduction to Jean-Luc Martinez, Les Antiques du Musée Napoléon, Édition illustrée et commentée des volumes V et VI de l’Inventaire du Louvre de 1810 (Paris: Fayard, 2004); Tatiana Auclerc, Notiz ‘Inventaire Napoléon’, in Marie-Anne Dupuy/Pierre Rosenberg, eds., Dominique-Vivant Denon: L’Oeil de Napoléon (Paris: Musée du Louvre, 1999).

3 On statistics in France, see Marie-Noelle Bourguet, Déchiffrer la France. La statistique départementale à l’époque napoléonienne (Paris: Édition des Archives contemporaines, 1989).

4 Jürgen Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung Der Welt: Eine Geschichte des 19. Jahrhunderts (München: Beck, 2011), 57.

5 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16–23 and 1 DD 33-44, 17 vol., see also Auclerc, Notiz ‘Inventaire Napoléon’.

6 Hamiaux/Martinez, De l’inventaire N à l’inventaire MR, and Paris, AMN, Z 3 (1810–1815); and Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey, Isabelle Le Masne de Chermont, and Elaine Williamson, Vivant Denon: directeur des musées sous le Consulat et l’Empire, Letter 1727 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1999), 610–611.

7 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 7, Objets d’arts et de sciences transportés au Musée 1793–1796.

8 Pierre Bourdieu, Distinctions: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984).

9 Hamiaux/Martinez, De l’inventaire N à l’inventaire MR, 434–435.

10 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 1, Catalogue des tableaux du Roi déposés au Louvre 1785.

11 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 2, Etat actuel des tableaux de la surintendance 1788.

12 Francis Haskell, The Ephemeral Museum: Old Master Paintings and the Rise of the Art Exhibition (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000).

13 Bénédicte Savoy, Tempel der Kunst: Die Entstehung des öffentlichen Museums 1701–1815 (Mainz: von Zabern, 2006), 11–12.

14 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 4, Inventaire des tableaux de la surintendance à Versailles 1794.

15 See Denon’s letter to Napoleon.

16 Jacques Wolff, Les insuffisantes finances napoléoniennes. Une des causes de l’échec de la tentative d’hégémonie européenne (1799–1814), in Revue du Souvenir Napoléonien, 397 (Sept./Oct. 1994), 5–20.

17 Bénédicte Savoy, Kunstraub: Napoleons Konfiszierungen in Deutschland und die europäischen Folgen (Wien: Böhlau, 2010), 142.

18 For research on the interactions between museums and markets in France at the end of the eighteenth century, see publications by Charlotte Guichard, especially Charlotte Guichard, Le marché au coeur de l’invention muséale? Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Lebrun et le Louvre (1792-1802), in Revue de synthèse (2011) 132-1, 93-118; and as yet unpublished research by Christine Godfroy-Gallardo.

19 Dupuy/Le Masne/Williamson, Letter 2967, Vivant Denon, 1018–1019.

20 Dupuy/Le Masne/Williamson, Letter 3038, Vivant Denon, 1042.

21 Dupuy/Le Masne/Williamson, Letter 2984, Vivant Denon, 1022.

22 Benjamin Peronnet and Burton B. Fredericksen, Répertoire des tableaux vendus en France au XIXe siècle, vol. I, 1801–1810 (Los Angeles: Getty Information Institute, 1998), 69.

23 Jean Penant, Ferreol Bonnemaison, un peintre et collectionneur toulousain méconnu, in L’Olifant: Journal de l’Association des Amis du Musée Paul Dupuy, 1 (1992), quoted in: Peronnet and Fredericksen, Répertoire des tableaux vendus en France au XIXe siècle, vol 13–14.

24 Marie-Claude Chaudonneret in AKL, vol 12, 580, with bibliography. Engravings: Ed. Pierre Didot with a text by Jean-Baptiste Emeric (Paris, 1818).

25 Pierre Rosenberg, Dominique Cordellier, and Peter Märker, Dessins français du musée de Darmstadt. XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles (Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2007), 32, note 18; Dupuy and Rosenberg, Dominique-Vivant Denon: L’Oeil de Napoléon, 114; Alain Pougetoux, La collection de peintures de l’impératrice Joséphine (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 2003), 34.

26 Dupuy/Le Masne/Williamson, Letter 2984, Vivant Denon, 1022–23.

27 Ibid.

28 Only a few works, particularly those included in the “French school,” are given no monetary value.

29 Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia, vol 2, Book XXXVI, see Francis Haskell/Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500–1900 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1982).

30 My thanks to Jörg Ebeling (Deutsches Forum für Kunstgeschichte in Paris) for this information.

31 The art dealer Pierre-Joseph-Ignace Lafontaine purchased a home for 137,500 francs in 1807, see Peronnet/Fredericksen 1998, note 22, 69.

32 Dupuy/Le Masne/Williamson, Letter 2850, Vivant Denon, 982.

33 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, Inventaire général du Musée Napoléon 1810, peintures t. I.

34 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, fol. 7, fol. 101–106, fol. 120, fol. 127.

35 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, Inventaire général du Musée Napoléon 1810, peintures t. II, fol. 304.

36 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 275.

37 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 18, Inventaire général du Musée Napoléon 1810, peintures t. III, fol. 428, fol. 480.

38 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 190.

39 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, fol. 124.

40 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 280.

41 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, fol. 65–66.

42 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, fol. 78.

43 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 144–145, fol. 150, fol. 265–268, fol. 331–334, fol. 241–242.

44 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 136, fol. 214, fol. 180 (the painting is Il trittico del epiphania, Master of Hoogstraeten (Savona, Museo del Tesoro del Duomo).

45 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 168.

46 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 348.

47 Paris, AMN, 1 DD 18, fol. 413.

48 Ernst Osterkamp, Raffael-Forschung von Fiorillo bis Passavant, in Studi germanici (nuova serie)

XXXVIII/3 (2000), 403–426.

49 Quoted in: Savoy, Tempel der Kunst, 412–413.

50 1813: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, 100; 1816: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 54, Musée Royal - Inventaire des tableaux de la collection du Roi 1815/1816, fol. 17; 1824: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 76, Inventaire général des Musées Royaux 1824, fol. 57.

51 1813: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 16, fol. 124; 1816: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 54, fol. 19; 1824: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 76, fol 43.

52 1813: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 17, fol. 280; 1816: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 54, fol. 37; 1824: Paris, AMN, 1 DD 76, fol. 116.

53 Osterhammel, Die Verwandlung der Welt, 62.