ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Robert Arlt / Lucie Folan

In 2016, the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) returned a 3rd-century stone panel to India. Titled Worshippers of the Buddha, the panel was bought in 2005 for US$595,000 from New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor. Arrested in 2011 and extradited to India, Kapoor has been linked to a pattern of illegal trade. Many items from his inventory match objects missing from Indian sites, resulting in numerous acts of restitution by international museums and collectors. At the time of acquisition, the NGA believed that the rudimentary documentation supplied by the vendor indicated a secure ownership history. The return was made after art historian Robert Arlt provided documentary evidence that Worshippers of the Buddha was excavated from the stūpa near the Buddhist site of Chandavaram in the 1970s, stolen from the site museum in 2001 and, by implication, illegally exported from India.

In this paper, Arlt describes how his research on the decorative panels of the stūpa near Chandavaram led him to learn of a series of violent robberies from the Chandavaram museum, and identify one of the stolen objects to the NGA collection. NGA provenance researcher Lucie Folan then discusses the sculpture’s fraudulent provenance as a tool of reassurance and misinformation, the failure of due diligence measures, and the political and practical implications of the Kapoor case. Without a reported theft, and with few published images of the excavation, Arlt demonstrates that researchers must look to obscure archaeological and art-historical records to accurately identify the origin of objects in museum collections and recognise looted or suspect items on the art market. The case study underscores the importance of information-sharing and collaboration with experts in and outside of source countries as museums grapple with the legacy of art crime.

Worshippers of the Buddha (fig. 1) – an ancient Indian limestone decorative panel that depicts two pairs of figures flanking an aniconic representation of the Buddha – was sold to the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in June 2005 for US$595,000 by art dealer Subhash Kapoor, six years before his arrest for suspected illicit trade in antiquities. In September 2016, the NGA returned the panel to India after art historian Robert Arlt alerted the Gallery to its archaeological origin and evidence that it was taken from the small under-resourced Chandavaram site museum, probably in the early 2000s, and illegally exported from India. This paper documents the true history of Worshippers of the Buddha, reconstructed from meagre archaeological and museum records. It then examines the NGA’s acquisition of the sculpture, its fraudulent provenance, and implications of the case. The study clarifies methods used to obtain and fence Indian cultural objects, deceive collectors and bypass ethical codes, and the inequalities that facilitate this.

Fig. 1: Chandavaram, Andhra Pradesh, India, Worshippers of the Buddha, 2nd century BC–2nd century AD, limestone, 96.5 x 106.7 x 12.7cm; when in collection of the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, accession number 2005.229; presently on display in the National Museum, New Delhi

Photograph © National Gallery of Australia

In 2011 New York art dealer Subhash Kapoor (born India, 1949) was arrested, and extradited to India in 2012, in relation to temple robberies and illicit trade in cultural property.1 According to police documents, Chola-period bronzes were reported missing from a temple in Suthamalli village in April 2008 and from Shri Puranthan in August 2008. Investigators allege they were stolen in 2008 and 2006.2 Later reports suggest that police were told of Kapoor’s involvement by his former girlfriend Paramaspry Punusamy, also an art dealer, after a legal disagreement in Singapore in 2010.3 While many details remain unclear, and the case is unresolved, most of the bronzes were later identified with items offered or sold through Kapoor’s Art of the Past gallery, through comparison with photographs of the missing sculptures taken in the 1990s by the Institut Français de Pondichéry (IFP).4 Police claim that the sculptures were transferred from India via a network of accomplices in India, Hong Kong, London and New York.5

In 2013, Kapoor’s sister was charged in New York with possessing stolen bronzes for the dealer.6 Later that year, Kapoor’s gallery manager, Aaron Freedman, and girlfriend, Selina (or Salina) Mohamed, pleaded guilty to conspiracy and criminal possession, and admitted to falsifying provenance histories for Kapoor.7 Court documents show that the dealer was under investigation in the United States for numerous alleged cultural property crimes, mostly involving Indian art. A Homeland Security agent stated, “Subhash Kapoor’s alleged smuggling of cultural artefacts worth more than an estimated $100 million makes him one of the most prolific commodities smugglers in the world today.”8 This illicit material is widely believed to have been accumulated over several decades, with some reports suggesting that Kapoor’s operations were based on illegal practices that his father, Ram Parshotam Kapoor (died 2007), engaged in from the 1960s or earlier.9

Related arrests have been made in India, notably of antiques dealer Govindaraj Deenadayalan in June 201610 and Kedar Batcha (or Basha), a former Tamil Nadu police officer, in 2017.11 Authorities believe that Kapoor and others were part of a network of thieves and smugglers, enabled by collusion and corruption, that habitually sourced antiquities from sites and temples in India for a receptive international art market.

The revelations had a profound impact on the international museum sector. Over around thirty years, Subhash Kapoor sold Asian art to private and institutional collectors, such as: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; Honolulu Museum of Art; Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio; Musée des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris; the Museum of Asian Art, Berlin; Singapore’s Asian Civilisations Museum; the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; and the NGA. Collectors also came to hold ex-Kapoor objects through gift and secondary purchase, and items once with the dealer probably remain, anonymously, on the market.

Museums declared objects bought from Kapoor, motivated in part by strong media interest. Concurrently, research was conducted by professional and amateur historians, archaeologists, curators, provenance researchers, journalists and officials in various nations. Online forums such as Chasing Aphrodite and Poetry in Stone sought to identify and collate suspect items, and expose possible negligence by collectors. Consequently, many items once with Kapoor were seized by government officers, identified as stolen or displaced antiquities, or found to have falsified provenance documents.12 Some works were relinquished simply due to an association with the dealer.13

Between 2002 and 2011, the NGA accumulated twenty-two works from Kapoor, including eleven Indian sculptures and a Shiva Nataraja, purchased in 2007 for US$5 million. The sculpture closely resembled the IFP photograph of the Shri Puranthan Nataraja,14 but a size discrepancy delayed declaration of a match.15 The correlation was confirmed in December 2013 when Freedman pleaded guilty to charges that itemised the fraudulent sale of the Shri Puranthan Nataraja to the NGA.16 The information indicated that the Nataraja was removed from India when the export of objects of its type and age was prohibited by The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972. As an illegally exported foreign cultural object, its import into Australia was unlawful under Australia’s Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act of 1986. Following a formal request from the Indian Government, the Australian Government repatriated the Nataraja, and a sculpture from the Art Gallery of New South Wales, on 5 September 2014. Other restitutions followed, by the US Government and institutions such as the Linden Museum in Stuttgart and the Asian Civilisations Museum. In September 2016, the NGA deaccessioned and returned two other Kapoor sculptures: Goddess Pratyangira and Worshippers of the Buddha. The compelling documentary evidence that informed the return of Worshippers of the Buddha is outlined below.

In the published Review of work done by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) for the season of 1965/66 Prasad introduced a Buddhist site close to Chandavaram, a village in the Prakasam District (Andhra Pradesh).18 Raghavalu, then Minister for Education of Andhra Pradesh, inspected the site in 1967; he suspected it to hold a large number of reliefs and hence suggested that it should be taken under the protection of the Department for Archaeology and Museums Andhra Pradesh (AP-DAM).19 His reasoning was, that if the ASI were to take over the site, the artefacts uncovered during excavations were in danger of becoming distributed to Museums outside of Andhra Pradesh, while the AP-DAM could help to “regain” what has been lost in the case of the Amaravati Sculptures.20 In accordance with his suggestions, the excavations started in 1972 under the supervision of the AP-DAM and continued until 1977.21

The main stūpa excavated at the site, turned out to be one of the biggest in southern India (fig. 2).22 The decoration, consisting of carved slabs on the stūpa’s dome and drum, was partly preserved in situ, although the site was reported to have been exploited for building material prior to excavation.23 A smaller decorated stūpa, temples and remains of substantial monastic habitations were found on the site, underlining its importance as a centre of Buddhism in the area.24

In the 1990s Murthy reported that forty-six (broken) casing slabs could still be found in situ around the drum and twelve more on the four āyaka-platforms.25 The remaining reliefs were stored in a site museum (constructed around 1989), though a few had been given to Hyderabad Museums.26 Since no final report was written reconciling those published during the excavations, Arlt attempted to synthesize the information available in his Masters Thesis to make it more accessible to scholars. In the process the discouraging discovery was made that a great number of reliefs had been stolen from the site museum in the early 2000s.27

Fig. 2: The exposed Chandavaram Stūpa as seen from the north, the hemispherical dome almost intact, northern and western āyaka-platforms clearly visible protruding from the drum, Chandavaram, Andhra Pradesh, India, 6 January 2004

Photograph © Monika Zin

Three violent robberies from the site museum were reported in the press: on 9 October 2000 two 2.74-metre-long reliefs were stolen from the Museum; the substantial size implying that the panels were once part of the stūpa dome’s décor. On 2 February 2, 2001 three more panels of the same size were stolen. Finally, three ornate pillars and a lotus medallion are reported to have been stolen on 23 March 2001.28 There is no available information about the thieves responsible, but similar robberies, including those officially linked to Kapoor, are known to have been carried out by individuals working for little financial gain within an international network of organised antiquities smugglers, many of whom received substantial profit.29 The then Superintendent of Police of Prakasam District Kumar Vishwajeet blamed the AP-DAM: “Our warning to shift the Chandavaram collection to the district headquarters Ongole was ignored,” as quoted by Menon in 2001, he did not rule out the involvement of organised crime. Congress legislator P. Govardhan Reddy postulated that “Repeated raids by a gang suggest the influential backing of political party activists and the collusion of local officials”.30

Shortly after the third raid on the museum, the remaining sculptures were exiled into a small storage building in the centre of Chandavaram. Surprisingly, some of the more than 2m long panels are not housed inside the building but on its porch. As the present co-author began comparing the published sculptures with those in the storage building, he was unable to locate a relief published by Murthy (fig. 3) and thus suspected it to be stolen.31 Unfortunately the photograph had been reproduced by Murthy without reference to its first publication, a time stamp and, most importantly, without mentioning that it was stolen.32

Fig. 3: Image of the Chandavaram panel matching Worshippers of the Buddha. Photograph taken around 1977. From Murthy, P Ramachandra, A Critical Study of the Hinayana Stupa at Chandavaram, in: G. Kamalakar, M. Veerender (eds), Buddhism: Art, Architecture, Literature & Philosophy, vol 2. Birla Archaeological & Cultural Research Institute, Sharada Publishing House, 2005: plate 3.

However, the missing sculpture was found to match an image of Worshippers of the Buddha available on the NGA’s online collection search, where it was identified as an object sourced from Kapoor, and a photograph published in an article by Kumar, showing the panel in the broken state in which it was initially offered to the NGA.33 Point by point comparison of the sculpture depicted in each of the photographs allowed Worshippers of the Buddha, an item from Kapoor’s inventory, to be confidently identified as the missing panel that was originally from the main stūpa at Chandavaram. Thus, Arlt contacted NGA provenance researcher Lucie Folan on 4 April 2016 and on 8 April provided her with two images of the relief in situ at the stūpa’s northern āyaka-platform as evidence that Worshippers of the Buddha had been excavated in Chandavaram during one of the 1970s’ campaigns (figs. 2, 4).34

Fig. 4: Chandavaram Stūpa as seen from the north. Worshippers of the Buddha in situ decorating the northern āyaka’s frontside. Photograph taken after 1972 during the excavations. From Subrahmanyam, B. / Reddy, E. S. Buddhist Archaeology in Andhra Pradesh, Hderabad: Department of Archaeology and Museums Andhra Pradesh, 2008: 28.

On 29 April, Prof. Akira Shimada (New Palz State University of New York) gave Arlt photographs of the interior of the Chandavaram Site Museum that he took in the 1990s before its closure in 2001. On 6 May, Arlt informed Folan that one of the photographs provided by Shimada featured Worshippers of the Buddha (fig. 5).35 This image, and the in situ photographs taken in the 1970s, confirmed that the ownership history of Worshippers of the Buddha, purported to date to 1969, was false. Illegal export was implied, as the export of ancient cultural material from India has been prohibited since The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972. The precise date and method by which Worshippers of the Buddha was removed from the Chandavaram site museum remains unconfirmed. In 2017 Varman quoted Galla (then adviser on international heritage to the A.P. Government, and Chief Curator, Amaravathi Heritage Centre and Museum): “Nobody knew that it was stolen. Interpol had not been informed.”36 It is certain, however, that it was taken unlawfully.

Many more sculptures stolen from Chandavaram have not been traced, and other objects sold by Art of the Past that might have been taken from the Chandavaram Site Museum are hard to locate.

Fig. 5: Image of the Chandavaram panel matching Worshippers of the Buddha on display at the Chandavaram site Museum before it’s closure in 2001.

Photograph © Akira Shimad

Recently a panel that was featured in one of Kapoor’s catalogues was seen in a branch of the Louvre in Abu Dhabi (fig. 6).37 Given that Kapoor was arrested in 2011 and his dealings have been publicly questioned, it seems surprising that this museum, which opened on 11 November 2017, would knowingly showcase a piece like this.38 Its iconography is similar to that of many sites in Andhra Pradesh. Two similar reliefs have recently been found in the bed of the Gundlakamma River near the Chandavaram Stūpa,39 and it is possible that the Louvre panel was taken from this or a similar site.

A relief that was auctioned from the collection of the Doris Wiener Gallery at Christie’s on 20 March 2012 is another candidate for a piece of art stolen from Chandavaram (fig. 7).40 Both the late Doris Wiener and her daughter Nancy Wiener have been implicated in the illicit trafficking of antiquities, and prosecutors allege that some of the items Nancy Wiener traded in were associated with or illegally obtained in India by Subhash Kapoor.41 The width of the relief, its rough rendering and the stone are very similar to some Chandavaram sculptures. If the present co-author is correct, the relief in question is only the middle part of a larger dome-slab.42 While there is no information about the sculpture’s true provenance, it is probable that the relief was illegally obtained from the Chandavaram region, possibly by members of Kapoor’s network.

In the media, the case of Chandavaram has been portrayed as a sad example of theft due to neglect.43 However, this is simplistic. The rediscovery of the true origin of Worshippers of the Buddha took more than a decade because only a very small number of images had been published in works that can be difficult to obtain, and few scholars had worked on the site, which ultimately lead to a dangerous lack of awareness among experts. Only once photographs or descriptions of the missing Chandavaram sculptures are published and disseminated will it be possible to establish what is missing.

The motivations, and logic behind the NGA’s acquisition of Worshippers of the Buddha help explicate the illegal transfer, and the role market countries play, often unwittingly, in illicit trade.

The NGA purchased the Chandavaram panel from Art of the Past in June 2005 with funds allocated by the Australian Government, to add depth and representativeness to the national collection of Asian art, and because of its art-historical value as “a major aniconic sculpture of great quality and narrative interest”.44 NGA curators attributed the sculpture to the Amaravati region and the third century, as per the dealer’s description, and titled it Worshippers of the Buddha. It was acquired in the context of broader strategies and historical circumstances. Since its opening in 1982, the NGA has displayed art representing “the high cultural achievement of Australia’s neighbours in southern and eastern Asia and the Pacific Islands”.45 The Asian art collections now encompass more than 5,000 works. In 2005, then NGA director Ron Radford outlined plans to: prioritise art from the Asia-Pacific region to “mirror the strategic importance of our geographic neighbours and our special allies”; seek high-quality Asian art; and open a prominent new Indian art gallery.46 South Asian art was emphasised to avoid duplicating other Australian public collections.47 Later, Radford commented on the financial attainability of Indian art, saying the NGA was being “opportunistic... we can just afford them now, we won’t be able to in a few years”.48 Worshippers of the Buddha entered the collection in this period, and was displayed in the Indian art gallery, opened in 2006. A media release stated, “Many of the sculptures and textiles on show have been acquired in the last eighteen months... broadening access to the vibrant and inspiring world of the art of the Indian subcontinent”.49

Fig. 6: Dharmacakra on pillar behind empty throne of the Buddha flanked by worshippers, limestone, 129,5 x 45,7 cm. From Art of the Past, Subhash Kapoor Celebrating Thirty Years on Madison Avenue. New York: Art of the Past, 2006: no. 3

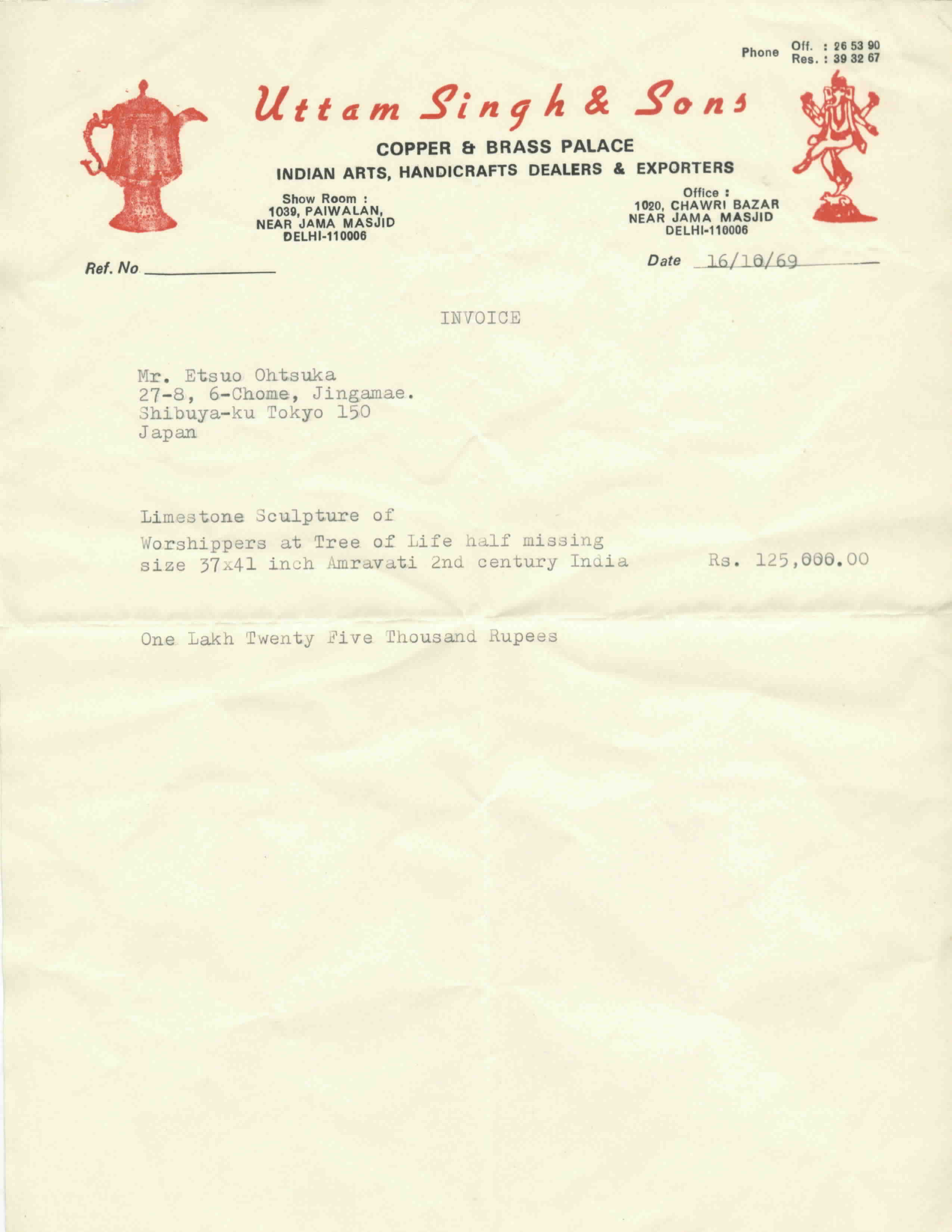

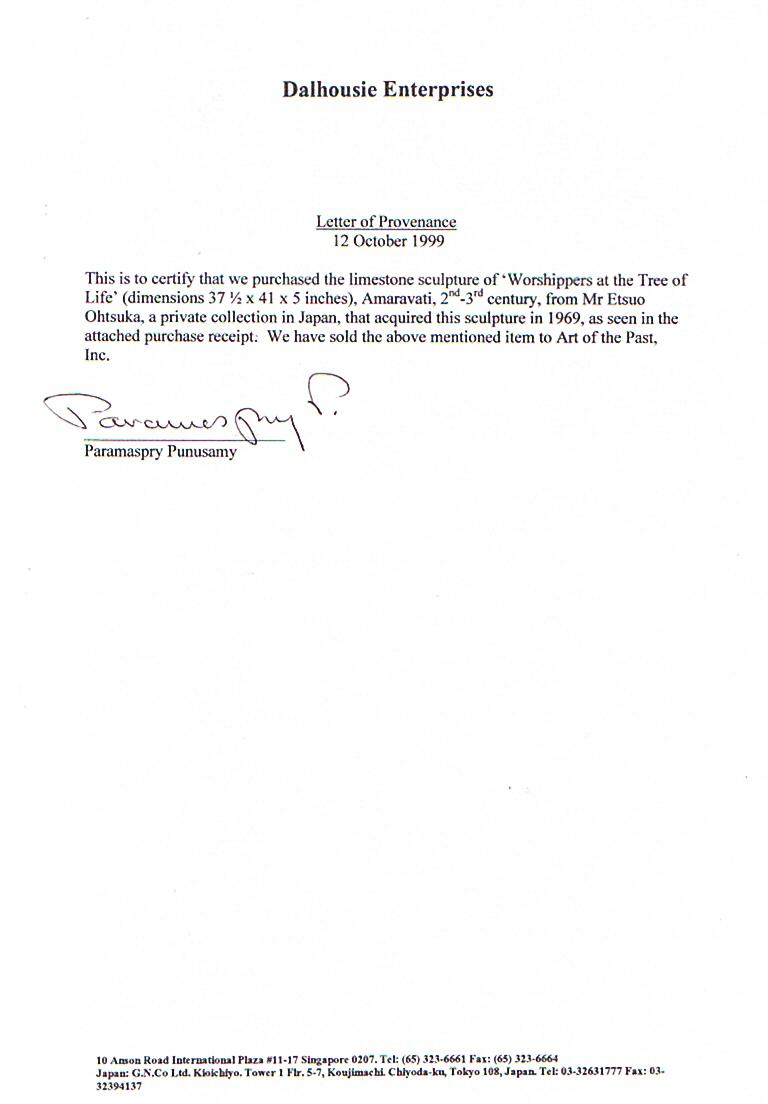

The acquisition of Worshippers of the Buddha was subject to provenance checks that have since been found inadequate. Art of the Past volunteered documents ostensibly from the sculpture’s former owners: a receipt from Uttam Singh and Sons to Etsuo Ohtsuka, dated 16 October 1969; and a letter signed by Paramaspry Punusamy stating that the sculpture was bought by Dalhousie Enterprises from Etsuo Ohtsuka and sold to Art of the Past, dated 12 October 1999.50 (Figures 8, 9). The addresses were checked and found to be authentic, but no information was found about Etsuo Ohtsuka or Ōtsuka and no attempt was made to contact either party as the provenance information was understood to have been provided in confidence.

Fig. 7: Dharmacakra on lion capital behind empty throne of the Buddha flanked by bovidae animals, limestone, 71.1 cm wide. From The Doris Wiener Collection (auction catalogue), Christie’s, New York, 20 March 2012.

The NGA accepted the documents as confirmation that the sculpture was bought and exported from India in around 1969. At the time, this was considered sufficient evidence that Worshippers of the Buddha was likely to have been legally exported, because historical art objects were allowed out of India (with an export licence) before The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act of 1972. Accordingly, the NGA believed that its import complied with Australian law. The provenance documents positioned export from country of origin as taking place before the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, the key international agreement that stimulated tightening of legal and ethical collecting standards. Moreover, Kapoor signed a letter of guarantee, agreeing to reimburse the NGA if provenance or authenticity were proven incorrect.51 Thus, the NGA did not consult Australian or Indian authorities.

The sculpture of Amaravati was researched, but did not uncover records matching Worshippers of the Buddha. Nor was it linked to a reported theft or a listing on Interpol’s stolen art database, and a certificate was obtained from the Art Loss Register.52 An expert opinion was requested from Robert Knox, Keeper of Oriental Antiquities at the British Museum until 2006 and author of Amaravati: Buddhist Sculpture from the Great Stūpa. Knox tentatively assessed the sculpture as genuine, but probably from a regional site. Significantly, he expressed concern about the provenance, writing that “1969 is conveniently... one year before the UNESCO Convention... There is no doubt, however... that this object was removed from India, in some year, in contravention of Govt of India antiquities laws”.53 Knox’s warning did not influence the acquisition, however, as it was received after the sculpture was accessioned.

Naturally, the vendor’s status was an important factor in the decision to purchase Worshippers of the Buddha. In 2005, Kapoor’s reputation had been cultivated over many years in the art trade, and was inferred by an extensive list of clients, loans and gifts to museums, and the public nature of his business.

Fig. 8: Uttam Singh and Sons purchase receipt supplied to the National Gallery of Australia by Subhash Kapoor of Art of the Past, New York

Photograph © National Gallery of Australia

With Kapoor’s arrest, it became clear that the measures taken by the NGA and other museums had allowed the acquisition of multiple illicit Indian cultural objects. To address widespread criticism, the NGA retained Mrs Susan Crennan AC QC, former justice of the High Court of Australia, to independently review its processes. She concluded that “... the NGA was the victim of a well-planned fraud by Art of the Past. These events illustrate the need to rely on sources of information other than a dealer, even if ostensibly reputable...”.54

In hindsight, though, the NGA was incautious to uncritically accept documents from unknown collectors with a vested financial interest in the sale as proof of the ownership and legality of Worshippers of the Buddha. It is now known that Kapoor used receipts from Uttam Singh and Sons to establish false purchase and export dates for other sculptures since found to be illicit, including Ardhanarishvara and Goddess Pratyangira returned to India by, respectively, the AGNSW and NGA. In 2014, journalists visited Uttam Singh and Sons at the address listed on the receipts. The owners recognised the letterhead but claimed the receipts were forged.55 No such contact was made by the NGA. The letter of provenance for Worshippers of the Buddha was written by a close associate of the dealer and, although Kapoor’s relationship with Punusamy was not known in 2005, contacting her or Dalhousie Enterprises may have revealed inconsistencies.

Fig. 9: Provenance letter supplied to the National Gallery of Australia by Subhash Kapoor of Art of the Past, New York

Photograph © National Gallery of Australia

The Kapoor controversy has prompted museums to divulge ownership information and publish documents that were previously kept confidential. As a result, it is now apparent that the same names were attached to multiple transactions.56 The documents offered by Kapoor generally position the export of objects in the years immediately before 1972, a time when collectors were increasingly aware of the prohibitions against looting foreign material, and therefore did not publicise the origins of objects, but before the development of relevant international agreements, ethical codes and laws. It is conceivable that these patterns may have been recognised as suspect far earlier if this information had been scrutinised by lawyers, police and or heritage professionals, particularly in India.

The sale of Worshippers of the Buddha relied on ignorance of the Chandavaram excavations, the inventory of the site museum, and the panel’s theft. This was partly achieved through deliberate misinformation, such as the false ownership details and generalised attribution of the panel. Mostly, however, the dealer seems to have simply exploited the difficulties of managing and safeguarding Indian cultural heritage, and his knowledge of standard museum practice. India is vast, with a population of over a billion, many living in poverty. Significant artistic and archaeological material is scattered across private and public collections and countless temples and sites of varying means, security and accessibility. Information documenting this material is incomplete, and held in diverse repositories. Museum professionals rarely have comprehensive knowledge of Indian archaeology, or the resources to consult disparate archives in India. Similarly, details of cultural heritage crimes in India, if reported to police, may not be transmitted beyond the local level. The theft of Worshippers of the Buddha was not reported, and the Chandavaram site museum is unlikely to have been aware of, or equipped to access, a fee-based register like the Art Loss Register. Moreover, recent accusations suggest that many thefts of Indian cultural heritage may have been deliberately concealed by corrupt law enforcers.57 While these factors contributed to the invisibility of the crime, it is plausible that Indian authorities may have alerted the NGA to the illicit nature of Worshippers of the Buddha, if they had been contacted in 2005. Kapoor was no doubt aware that the NGA, like other museums, did not habitually consult source-country authorities, or seek retrospective export approval.

The Kapoor cases have had significant consequences for Australia and the NGA. Since 2014, NGA director Gerard Vaughan AM has suspended acquisitions of Asian antiquities and introduced stricter due diligence guidelines to include consultation with source countries. The scope of the Asian Art Provenance Project was extended to encompass an assessment of the ownership histories of all objects in the Asian art collection. All verified provenance details are to be published online to elucidate Asian art collecting histories and expose ‘red flags’ to scrutiny. Undeniably, entanglement in the Kapoor controversy tarnished the NGA’s reputation and placed strain on the Australia-India relationship. It is significant that the NGA and Australian Ministry for the Arts approved the voluntary repatriation of Worshippers of the Buddha prior to a request from the Government of India and without either a formally reported theft or financial compensation. The swift restitution was intended to condemn the illicit trade in Asian art and ameliorate reputational and political damage.58 After its return, Worshippers of the Buddha was shown at the National Museum of India and is believed to have generated considerable goodwill.

The case of Worshippers of the Buddha illustrates that art crime has continued to taint the international art market into the twenty-first century, despite increased access to archaeological records through digitisation, international cooperation, and the ethical codes followed by museums and reputable collectors. As in many instances of looting in developing nations, economic and political inequalities, greed, corruption and the inaccessibility of information, as well as collector complacency, are shown to have enabled the unlawful movement of Worshippers of the Buddha from source to market, and conceal its loss for many years. While restitution was made, it was based on tenuous foundations. Thus, the study exemplifies the importance of accessible information in reconstituting archaeological sites and combatting art crime, and the urgent need to improve consultation with source countries and channels for reporting art crimes, and commit resources to museums, archives, researchers, and projects to safeguard cultural heritage and prevent illicit material from reaching the market.

Robert Arlt is a research associate at the institute for Indology and Tibetology at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. Lucie Folan is curator of Asian Art at the National Gallery of Australia.

1 A. Selveraj, Antique smuggler Subhash Kapoor to be extradited from Germany, in Times of India, 12 July 2012 (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/Antique-smuggler-Subash-Kapoor-to-be-extradited-from-Germany/articleshow/14739379.cms; accessed January 2018); A. Matthews, The man who sold the world, in GQ Magazine, 25 December 2013 (https://www.gqindia.com/content/man-who-sold-world/; accessed January 2018).

2 Idol Wing of the Tamil Nadu Police Department, Status of cases (http://www.tneow.gov.in/IDOL/status_info.html; accessed January 2018); Subhash Chandra Kapoor v. Inspector Of Police (Madras High Court writ petition, 3 April 2012: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/14478654/; accessed January 2018)

3 Jamie Schram, NY art dealer stashed millions in ‘stolen’ Indian art treasure, in New York Post, 27 July 2012 (https://nypost.com/2012/07/27/ny-art-dealer-stashed-millions-in-stolen-india-treasure/; accessed January 2018); Matthews, The man who sold the world; Khushwant Singh, Art dealer wants antiques back, in The Straits Times, 10 February 2010 (http://www.asiaone.com/News/the%2BStraits%2BTimes/Story/A1Story20100210-197722.html; accessed January 2018); Huang Lijie, Asian Civilisations Museum checks items from disgraced art dealer, in The Straits Times 15 December 2013 (http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/asian-civilisations-museum-checks-items-from-disgraced-art-dealer; accessed January 2018).

4 Idol Wing of the Tamil Nadu Police Department, Idol Wing CID: Udayarpalayam police station Crime Number 65/2008 and Vikramangalam police station Crime Number 133/2008 (http://www.tneow.gov.in/IDOL/idols_foreign.pdf; accessed January 2018); personal communication with Dr N. Murugesan, Institut Français de Pondichéry, File note, NGA File Number 04/0020; V. Kumar, Poetry in Stone (http://poetryinstone.in/; accessed January 2018); J. Felch, Chasing Aphrodite (https://chasingaphrodite.com/?s=subhash+kapoor; accessed January 2018); U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE HSI partners with major art collector to recover stolen idol from India, 7 January 2015 (https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-his-partners-major-art-collector-recover-stolen-idol-india; accessed January 2018).

5 A. Selveraj, Stolen idols case: Hong Kong woman, UK man aided Subhash Kapoor, in Times of India, 5 August 2012 (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/Stolen-idols-case-Hong-Kong-woman-UK-man-aided-Subhash-Kapoor/articleshow/15356959.cms?referral=PM; accessed January 2018); Matthews, The man who sold the world, 2013.

6 People of the State of New York v. Sushma Sareen, No. 2013-077096, (New York Supreme Court complaint, October 7, 2013: https://www.scribd.com/doc/175894092/Sushma-Sareen-Complaint; accessed January 2018).

7 People of the State of New York v. Aaron Freedman, No. 2013-091098, (New York Supreme Court plea agreement, 4 December 2013: https://www.scribd.com/document/189440692/NY-vs-Aaron-Freedman; accessed January 2018); People of the State of New York v. Selina Mohamed (New York Supreme Court complaint, 20 December 2013: https://www.scribd.com/document/193125267/Selina-Mohamed-Complaint; accessed January 2018).

8 News release by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement of 12 April 2012 (https://www.ice.gov/news/releases/ice-seizes-statues-allegedly-linked-subhash-kapoor-valued-5-million; accessed 9 January 2018).

9 Matthews, The man who sold the world, 2013; Narayan Lakshman, The man who stole gods, in The Hindu, 21 October 2017 (http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/the-man-who-stole-gods/article19892698.ece; accessed January 2018).

10 Gargi Gupta, A house full of stolen antiques, in Frontline, 8 July 2016 (http://www.frontline.in/the-nation/a-house-full-of-stolen-antiques/article8756071.ece; accessed 2018).

11 A. Selveraj, TN idol theft case: absconding DSP Kader Batcha arrested, in The Times of India, 14 September 2016 (https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/tn-idol-theft-case-absconding-dsp-kader-batcha-arrested-/articleshow/60509349.cms; accessed January 2018).

12 V. Kumar, Poetry in Stone (http://poetryinstone.in/; accessed January 2018); J. Felch, Chasing Aphrodite (https://chasingaphrodite.com/?s=subhash+kapoor; accessed January 2018).

13 Tom Mashberg, Museums Begin Returning Artifacts to India in Response to Investigation, in The New York Times, 7 April 2015 (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/08/arts/design/museums-begin-returning-artifacts-to-india-in-response-to-investigation.html; accessed January 2018).

14 Institut Français de Pondichéry / École française d’Extrême-Orient, image number 11207.

15 Email communication, Dr N Murugesan, Institut Français de Pondichéry, to NGA Asian art curator Melanie Eastburn, 2013, NGA File Number 04/0020.

16 People of the State of New York v. Aaron Freedman.

17 Parts of the following paragraphs are based on an earlier publication: Robert Arlt, Die Rückkehr der Verehrer des Buddha – The Safety of Indian Art, in: Indo-Asiatische Zeitschrift 20/21 (2017), 15-21.

18 See ASI-R 1965-66, 4; the position of the site given in the Review is erroneous. Its correct location can be found using the following coordinates: 15°56’01.7”N 79°25’46.6”E. While the outcome of every season of the excavations can be found in the respective reports cited below, later studies concerning its sculptures (Reddy 2005; Reddy 2009: 42; Reddy 2014, Zin 2012) and structural remains (Murthy 1997; Murthy 2005; Subrahmanyam 2005) have been published subsequently. Since most of the sculptures and a plan of the site have remained unpublished, Arlt (forthcoming) tries to fill some of the gaps concerning these points. For various reasons the earliest phases of the site were thought to date back to 250 B.C. (AR-AP-DAM 1974/1975: 10) or 200 B.C. (Murthy 2005, 298) or even 1st to second century B.C. (Subrahmanyam 2005, 464). Single sculptures have been dated to the first (Zin 2012, 761), or first to second and later centuries A.D. (Reddy 2005, 82-82).

19 Protocol of the Andhra Pradesh legislative assembly debate (AP-LAD) held on 1 March 1968: 236-8.

20 The sculptures of Amaravati gave their name to an artistic school that played a formative role in the early history of Buddhist and South Asian art. Most of these sculptures are now in museums far from Amaravati, the most famous collection is in the British Museum in London.

21 Summaries of the respective seasons’ findings, together with few photographs, have been published in the Annual Reports of the AP-DAM (AR-AP-DAM) and, in abbreviated form, in the Reviews of the ASI (R-ASI). See AR-AP-DAM: 1972/73, 13-14; 1973/74, 2-3; 1974/75, 8-13; 1975/76, 12-16; 1976/77, 17-24; R-ASI: 1972/73, 3; 1973/74, 7, 35; 1974/75, 6-7; 1975/76, 3-4; 1976/77, 9-10, 58.

22 A stūpa is a manmade mount, roughly hemispherical in shape that often holds relics. Larger stūpas were often the centre of Buddhist worship. The large Chandavaram Stūpa had a diameter of ca 32m and a height of 7 to 8m, while the circular platform on which it rested had a diameter of almost 50m. See Murthy 1997, pl. X; for figure 2 see http://photos.wikimapia.org/p/00/01/84/75/94_big.jpg (accessed January 2018).

23 See protocol of AP-LAD 1 March 1968: 237 and AR-AP-DAM: 1972/73, 13.

24 The excavations on the large stūpa and a second smaller one started with the first campaign, (AR-AP-DAM: 1972/73, 13-14). Excavations on the structures situated to the north of the larger stūpa started at a later time and revealed at least three distinctive monastic complexes with meditation cells and assembly halls (1976/77, 17-24).

25 Ibid., 136. Āyaka-platforms are platforms protruding from the drum of the stūpa in the cardinal directions.

26 For a reference to the construction of the site Museum see Ramalakshman 2002, 241. At present some pieces are stored in the Hyderabad Museum (P. 66646, P. 66647, P. 66650, P. 66651) while at least three are shown in the Amaravati Museum, two of which feature an older number from the Hyderabad Museum: AM-14 (old number: P.66454), AM-15 and AM-16 (old number: P.6645). Judging from the inventory numbers, we can estimate that at some point at least nine reliefs were transferred to the Hyderabad Museum.

27 For this and similar cases see Pachauri (2006) as well as the annual reports of the National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs (http://ncrb.nic.in/StatPublications/CII/ PrevPublications.htm; accessed January 2018).

28 Amarnath K. Menon, Easy Pickings. A series of robberies at remote Buddhist sites in Andhra Pradesh exposes the neglect of excavated treasures, in India Today, 30 July 2001 (http:// indiatoday.intoday.in/story/series-of-robberies-at-remotebuddhist-sites-in-andhra-pradesh-exposes-neglect-of-excavatedtreasures/1/230807.html; accessed January 2018).

29 See, for example, Idol Wing of the Tamil Nadu Police Department, Status of cases http://www.tneow.gov.in/IDOL/status_info.html (accessed January 2018).

30 Ibid.

31 Murthy, 2005: pl. 3.

32 The image was first published in AR-AP-DAM 1973/1974: pl. 6. However, due to the scarcity of publications by the AP-DAM in European libraries (the only near to complete set is in Tübingen University) the present co-author only managed to get hold of this report on 17 May 2017.

33 S. V. Kumar, India has abandoned its Gods, in Swarajya Magazine, 24 April 2015 (http://swarajyamag.com/culture/india-has-abandoned-its-gods/; accessed January, 2018).

34 For figure 4 see: Subrahmanyam / Reddy, 2008: 28.

35 The authors would like to thank Akira Shimada for permission to publish this photograph.

36 P. Sujatha Varma, A.P. to go digital to secure ancient icons, in India Today, 28 June 2017 (http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-andhrapradesh/ap-to-go-digital-to-secure-ancient-icons/article19157826.ece; accessed January 2018).

37 The image was published in Art of the Past 2006, no. 3. About the alleged sighting in the museum see R. Sivaraman, Artefact at Louvre raises doubt, in The Hindu, 12 November 2017 (http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-tamilnadu/artefact-at-louvre-raises-doubt/article20260385.ece; accessed January 2018); Vijay Kumar (vj @ poetryinstone), 11 December 2017 (https://twitter.com/poetryinstone/status/940182543613042688; accessed January 2018).

38 The photograph of the relief included in the articles above is different from the one published by Art of the Past.

39 Anonymous, 1st Century Buddhist panels found, in The Hans India, 27 November 2016 (http://www. thehansindia.com/posts/index/Andhra-Pradesh/2016-11-27/1st-Century-Buddhist-panels-found-/265796; accessed January 2018).

40 Christie’s sale 2640, New York, 20 March 2012, lot 30 (http://www.christies.com/ lotfinder/sculptures-statues-figures/a-limestone-relief-with-thedharmachakra-india-5538683-details.aspx#top; accessed January 2018).

41 Tom Mashberg, Prominent Antiquities Dealer Accused of Selling Stolen Artifacts, in The New York Times, 21 December 2016 (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/21/arts/design/ prominent-antiquities-dealer-accused-of-selling-stolenartifacts.html; accessed January 2018); People of the State of New York v. Nancy Wiener, No. SCI-05191-2016, (Criminal Court of the City of New York complaint, 21 December 2016: http://www.artcrimeresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Wiener-Complaint.pdf; accessed January 2018).

42 The middle section of most dome-slabs displays a wheel or dharmacakra as a symbol for the Buddha’s first sermon. Until now, no example of a dharmacakra flanked by animals is reported from Chandavaram, but the dome-slabs prove to be quite different in detail. To the connoisseur the animals might look unusual at first, but a very similar rendering can be found on a relief excavated in Amaravati, housed in the British Museum; see Knox, 1992, 111 f, Nr. 51.

43 See Amarnath K. Menon, Easy Pickings. A series of robberies at remote Buddhist sites in Andhra Pradesh exposes the neglect of excavated treasures, in India Today, July 30, 2001 (http:// indiatoday.intoday.in/story/series-of-robberies-at-remotebuddhist-sites-in-andhra-pradesh-exposes-neglect-of-excavatedtreasures/1/230807.html; accessed January 2018).

44 Submission for acquisition of Worshippers of the Buddha, NGA File Number 04/0020.

45 Daryl Lindsay, Report of National Art Gallery Committee of Inquiry (Australian National Gallery: Canberra, 1966).

46 Ron Radford, A Vision for the National Gallery of Australia (National Gallery of Australia: Canberra, 2005: https://nga.gov.au/aboutus/ips/pdf/ngavision2005.pdf; accessed January 2018).

47 Radford, ibid.

48 Ron Radford quoted in: National Gallery showcases Indian art in ABC News (2006) http://www.abc.net.au/news/2006-08-31/national-gallery-showcases-indian-art/1252734 (accessed January 2018).

49 NGA media release, National Gallery of Australia to open Australia’s first gallery of the Art of the Indian subcontinent (2006).

50 Documents on NGA File Number 04/0020.

51 Subhash Kapoor, Letter of Guarantee (NGA File Number 04/0020: 20 June 2005).

52 Art Loss Register reference: NGAU 250-1, 19 July 2005.

53 Robert Knox to Robyn Maxwell (NGA File Number 04/0020: received July 2005).

54 Susan M. Crennan, Review: Asian art provenance project (National Gallery of Australia: Canberra, 2015) http://nga.gov.au/AboutUs/press/pdf/NGAIndependentReview.pdf.

55 Amanda Hodge, Leap of faith to fall for this bazaar story, in The Australian, 13 March 2014 (http://www.theaustralian.com.au/arts/visual-arts/leap-of-faith-to-fall-for-this-bazaar-story/news-story/dc3b184dfdad35bcd8391e7622a8784b; accessed January 2018).

56 J. Felch, Chasing Aphrodite (https://chasingaphrodite.com/?s=subhash+kapoor; accessed January 2018).

57 Narayan Lakshman, The man who stole gods, 2017.

58 Submission for deaccession of Worshippers of the Buddha (July 2016) NGA File Number 04/0020