ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Marie Tavinor

This article examines the introduction of two waves of Scottish artists at the newly-founded Venice Biennale in 1897 and 1899 and considers how the Venetian venture negotiated the need to innovate with the imperative to build up its own reputation. Using hitherto unpublished archival material, it touches upon a number of issues regarding marketing practices, art market flows and the consumption of art at the international level.

As with Scottish art, the next Venetian Salon is preparing new, wonderful revelations for the Italian public and artists, who will discover artistic intentions and conceptions that they did not suspect.1

The Esposizione internazionale della città di Venezia (henceforward called Venice Biennale) launched in 1895 was first and foremost a manifestation of prestige expressed through the gathering of well-established artists of international reputation such as Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1898), Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824-1898) or Giovanni Boldini (1842-1931). It could be argued that in so doing the Biennale attempted to meet the first of its founding objectives, i.e. “to show the public the most noble and characteristic examples of contemporary artistic creation”.2 The second exhibition held in 1897 aimed to increase the “symbolic capital” of the venture not only with the reputation of the exhibitors but also with the introduction of lesser-known artistic trends, as expressed in the newspaper article quoted above. In that respect, it sought to adhere to its second founding objective which was to “extend and refine aesthetic culture”.3 This article examines the introduction of two waves of Scottish artists at the Venice Biennale in 1897 and 1899 and considers how the Venetian venture negotiated the need to innovate with the imperative to build up its own reputation.

The Scottish school will be one of the major attractions of the Venetian exhibition, as it has only been showed at two exhibitions on the Continent so far: at the Secession and at the Glaspalast.4

This statement made by the Venice Biennale General Secretary Antonio Fradeletto (1858-1930) a few months before the opening of the second Biennale highlighted the strategic importance of the Scottish section as signalling innovation. Indeed, together with Room N which contained a selection of historic and contemporary Japanese prints and Room L which showed Scandinavian and Russian artists, the Scottish room fostered the international ambition of the venture whilst bringing an exotic flavour to Venice.

In 1897, Scottish painters presented an array of landscapes, portraits and genre scenes. Most landscapes emphasised a bucolic and poetic rendering of rural life; many showed the influence of Whistlerian tonalism combined with the late style developed by Camille Corot from the 1860s onwards. For example Robert Macaulay Stevenson (1854-1952) sent four dreamy nocturnal landscapes, one of which took its title from the Hymn by Joseph Addison (1672-1719) Soon as the Evening Shades Prevail/ The Moon Takes Up the Wondrous Tale. This example of literary title was uncharacteristic as many paintings were otherwise titled generically as “Scottish landscape” or they gave a cursory indication of the time of day or year.5 Others looked at the Hague School for a further model in tonal approach.6 Portraits also showed the same search for values and tonal harmonies derived from the Whistlerian model whilst their sitters were mostly feminine figures, elegant ladies or charming children. Francis Henry Newbery (1855-1946) sent A Pair of Blue Eyes, a portrait of a young girl wearing a dark coat and white hat, perhaps his sister Mary, created with vigorous brushstrokes [fig. 1].7

Fig. 1: Francis Henry Newbery, A Pair of Blue Eyes, c. 1896, oil on canvas, 112x76cm (Civici Musei e Gallerie di Storia e Arte, Udine).

Reproduced in the Seconda esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia, Catalogo illustrato (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1897), unpaginated.

These paintings presented an array of different artistic trends testifying to the dynamic Scottish art scene. From Edinburgh and the Royal Scottish Academy, traditionally the leading art institution in Scotland came a few notable artists, for example Mason Hunter (1854-1921), or Robert Brough (1872-1905), who exhibited a pair of religious scenes whose square brushstrokes showed that he had also trained in France. The most important group of artists however belonged to the “Glasgow School”. Glasgow was at the time a rallying place for artists and a growing artistic competitor to Edinburgh since the mid-1880s. Some of these artists had also studied on the Continent while others had never left Scotland. While some pursued an individual agenda others had developed strong ties of friendship, as for example James Guthrie (1859-1930) and Edward Walton (1860-1922) or James Paterson (1854-1932) and William Macgregor (1855-1923). Some of these men had loosely coalesced into a group and the leading artists were generally thought to be James Guthrie, Edward Walton and John Lavery (1856-1941). All three sent portraits to Venice in 1897: James Guthrie sent one, Portrait of Lady Hamilton, while Edward Walton consigned two family portraits, his daughter Cecile Walton and his wife Mrs Walton. Irish-born John Lavery, who enjoyed a growing reputation for society portraiture, sent the portrait of A Lady as well as one of the flamboyant founder of the Scottish Labour Party, Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham (1893, private collection). In addition some women also sent their works: Constance Walton (1865-1960), Edward’s sister, contributed delicate watercolours inspired from Japanese art both in 1897 and in 1899, while some of the Glasgow “Girls” such as Bessie MacNicol (1869-1904) sent two oil paintings in 1897.

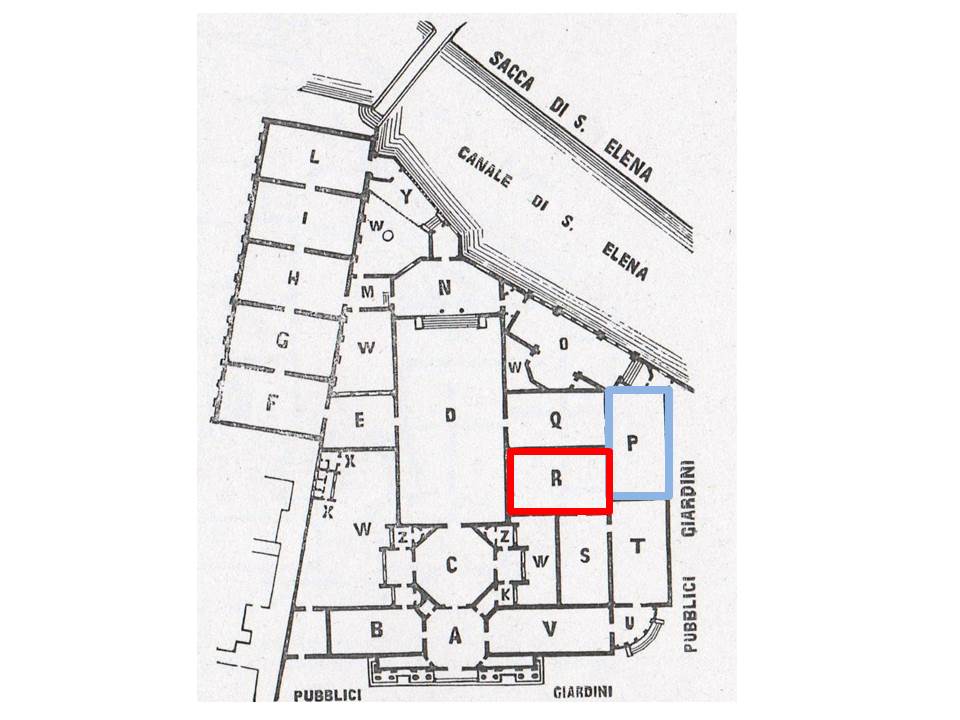

The Scottish section, placed in Room R, contained seventy-one paintings sent by a group of thirty-four young Scottish men and women. Its size was double that of its British neighbour placed in Room P which displayed thirty-seven paintings by nineteen artists [fig. 2]. In accordance with what Antonio Fradeletto had predicted, the Scottish Room attracted overwhelmingly positive reviews, which presented it as “a major success”.8 Indeed most critics were charmed by the poetic rendering of Scottish landscapes and simple everyday scenes. While British art critic Walter Shaw Sparrow had once described Glaswegian painters as “a disbanded orchestra of styles”,9 Italian art critics were keen to emphasise the artistic and brotherly bonds existing between all Scottish artists. They saw in the landscapes and the portraits exhibited in Venice a unity of style, a harmony of views. Indeed the catalogue of the exhibition described the Scottish works as linked by “organic affinity”.10 One of the leading art critics of his time and future, General Secretary of the Biennale Vittorio Pica (1862-1930) presented these painters as an artistic brotherhood displaying “a similarity of temperament” and “an obvious spiritual homogeneity in their works”.11 This no doubt aimed to contrast them to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood founded half a century earlier. The few paintings which had been exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1895 had revealed to the Italian public the illusory nature of the label bonding these artists together.12

Fig. 2: Building of the Artistic Exhibition [Edificio dell’Esposizione artistica], 1897.

Reproduced in the Seconda esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia, Catalogo illustrato (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1897), unpaginated.

Seeing these Scottish artists as a unified artistic group may not have corresponded to the artistic reality, yet it was certainly due to their presentation in a separate room. This physical separation represented a convenient marketing tool, which in an increasingly decentralised art market with a greater flow of artworks, helped identify them into a recognisable entity. This marketing technique was not devised in Venice; rather the Venetian venture replicated the successful presentation of these artists in other cities. It seems to have been used first at the 1888 International Glasgow Exhibition, then at the London Grosvenor Gallery in 1889 and in 1890, a turning point in the career of the “Glasgow School”.13 Hailed by some critics as “so like one another” in spite of their diverging aesthetic agendas, it is when art critics started using the term “School” to describe them.14 Although it was not possible to find information on the economic impact of such labelling yet, the group identity certainly created an echo of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as it was picked up in Venice. On both occasions, this strategy contributed to attract the attention of foreign art critics.15

Indeed, after seeing these Scottish painters in London, Adolf Paulus (1851-?) and Walter Firle (1859-1929), the representatives of the Munich Artists’ Association (Münchner Künstlergenossenschaft), invited them as a “feature” of the upcoming 1890 exhibition, i.e. with a room of their own. Like in Venice, the exhibition of Scottish art in Munich was not restricted to one particular group; rather it coalesced different artistic trends and became a regular exhibition feature of the Glaspalast and at the Secession Gallery on Prinzregentenstraße from 1890 onwards. In Germany several Scottish painters were awarded gold medals: Alexander Roche (1891), Robert Macaulay Stevenson (1893), Grosvenor Thomas (1901), Edinburgh-born Thomas Austen Brown (1896) whose portrait of Mademoiselle Plume-Rouge was acquired by the Munich Pinakothek that year. An art critic writing for the Münchner Neueste Nachrichten emphasised the unity of these painters: “They are closely akin to each other; however different they may be, one feeling, one aim, one power unites them; they have sprung from the same source.”16

It was in Munich where Antonio Fradeletto discovered these Scottish artists in 1896. He then decided that they should feature prominently in the second edition of Esposizione internazionale. In November 1896, Fradeletto created a summary of the exhibition to come for local and national journalists. Listed by country, the report underlined the best artists and sometimes gave a few more details as to their credentials. In the case of the Scottish section, all the names were underlined and Fradeletto added underneath: “I have had to select but in truth all twenty-five artists should be named”.17 He further intimated to the journalists: “Please insist on the importance of that section”, which was faithfully carried out.

With the Scottish Room in 1897, Antonio Fradeletto decided to implement what will be called here “a replication strategy” whereby he identified a successful group of artists in another art centre and decided to recreate the same exhibiting conditions, i.e. a single room, with the same effect, i.e. the creation of an easily identifiable entity. Although these Scottish artists were already well-known in Germany and some enjoyed a growing success in Britain, the innovation factor worked for the Italian public, who was still catching up with international trends at the time. This strategy served to enhance the reputation of the newly-founded Venetian venture and contributed to its income as the Venice Biennale Sales Office took a 10% commission on sales.

In 1899, a second wave of innovation came from Scotland to Venice in the shape of a group of twenty decorative works from the Glasgow School of Art selected and sent in by its Headmaster Francis Henry Newbery.18 His wife Jessie Newbery (1864-1948), Tutor of Embroidery and Glasgow “Girl”, sent an embroidered cushion and carpet, a silver pin and a gilt-bound book. John Guthrie, a member of the Glasgow School mentioned earlier, exhibited a sketch for stained glass.

The crux of the section of “Scottish decorative arts” however comprised the emerging group of “The Four”, i.e. Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928), Herbert MacNair (1868-1955) and the Macdonald sisters, Frances (1873-1921) and Margaret (1864-1933). Their idiosyncratic interpretation of Art Nouveau mixed with Eastern and vernacular elements later known as the “Glasgow Style” was formed during the 1890s and the group separated in 1899 when Frances and Herbert got married and left Scotland for Liverpool. The thirteen works they sent to Venice could arguably be seen as the first organic contribution they produced for an international platform. Both Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Herbert MacNair sent an array of works reflecting the breadth of their activities. As he was working on Catherine Cranston’s tearooms in Glasgow at the time, Mackintosh showed his Japanese-inspired decorative painting Princess Uty. He also exhibited a lithographic poster created for The Scottish Musical Review; the catalogue did not give details of the subject matter, which now makes it difficult to identify as Mackintosh produced a few in the mid-1890s.19 Herbert MacNair sent five exhibits, half of which centred on home design, such as silver sugar tongs and a silver toast rack, while he also sent a poster and two panels representing The Dead Mother and Rose. Lastly the two Macdonald sisters contributed a poster, generically presented as “design for advertisement” in the catalogue. They also showed two pairs of their work on metal: beaten bronze fingerplates of Present and Future and a pair of beaten aluminum panels entitled The Star of Bethlehem and The Annunciation.

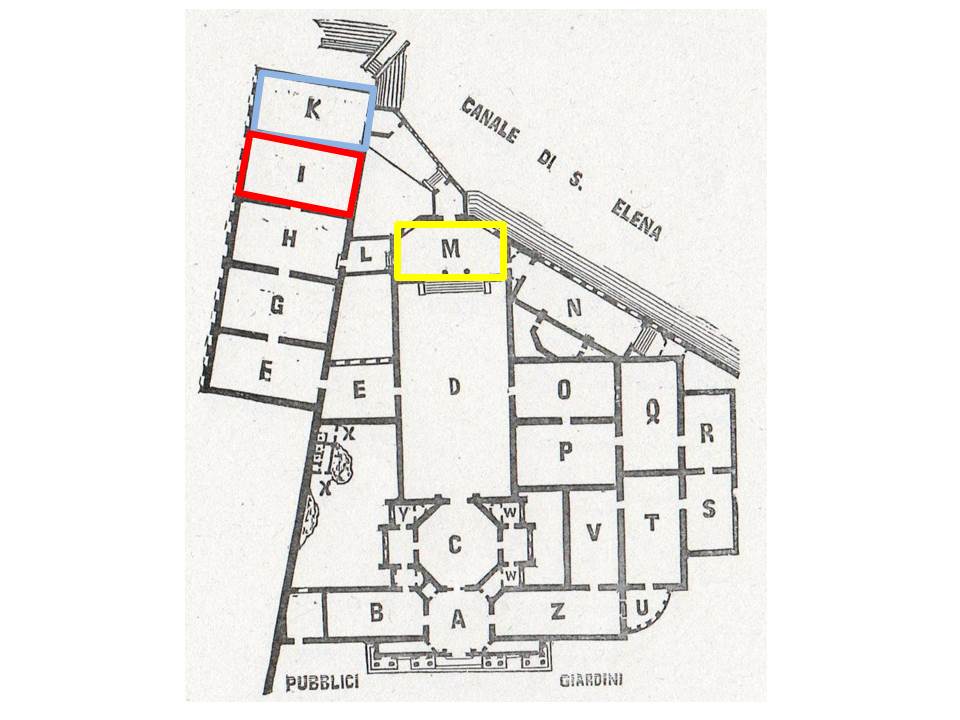

These Scottish decorative arts were shown in Room M, where they were displayed alongside a group of eight bronze sculptures by Belgian artist Pierre Charles Van der Stappen (1843-1910), at the time a correspondent of the Viennese Secession [fig. 3]. Furthermore other avant-garde sculptors were included in this room such as Paul Du Bois (1859-1938), a founding member of Les Vingt in Brussels. This shows that the Biennale organisers aimed at a display conveying aesthetic unity, rather than a display centred on geographical unity as was the case with the Scottish section in 1897. It therefore signalled innovation from a different perspective.

Fig. 3: Venice Biennale, 1899 plan, Scottish decorative arts shown in Room M

Contrary to what happened with the Scottish painters in 1897 no specific intimation to local and national journalists was produced, as least to our knowledge. Likewise, works by “The Four” were not illustrated in the exhibition catalogue. Perhaps as a result, what seems to us an important aesthetic innovation did not attract many comments in the press. On the other hand, general comments were made: for example Vittorio Pica expressed disappointment that the decorative arts should not be given more prominence and more space.20 Pica’s wish was carried out in Venice from 1903 onwards, as a result of the successful Turin exhibition in 1902, which gave pride of place to the decorative arts and in which works by “The Four” featured prominently.21

However, comments published in the Italian press in 1902 gave a clue as to why Scottish decorative arts received such a lukewarm reception in Venice. Alfredo Melani remembered “sparse praise and a great amount of disdainful whispers… [he] heard Italian decorators laugh at the Scottish panels similar to those on display in Turin today. They laughed at their elongated, lanky and skinny figures, making coarse jokes”.22 It therefore appears that whilst the Scottish decorative arts section was given a prominent place in the physical space of the exhibition, the public seemingly did not appreciate its pared down and austere aesthetic pointing to a modernist taste. Other comments illuminated the importance of the physical space itself.

Contrary to Venice, “The Four” were given three rooms in Turin which they arranged as an interior. The Studio praised the unity of the Scottish section, in which light and proportions served its aesthetic purpose.23 The different receptions of “The Four” in Venice and Turin point to the importance of display choices and to the crucial emphasis on Gesamtkunstwerk in fin-de-siècle exhibition platforms. The Venice organisers may have been hampered by practical considerations such as shortage of space or time, or by their lack of experience in displaying decorative arts. “The Four” did not renew their participation to the Biennale after 1899.

Yet the presence of “The Four” in Venice is nevertheless an important landmark as this group exhibition antedated their famous contribution to the Vienna Secession in November-December 1900 and to the 1902 Turin exhibition, traditionally presented as introducing Art Nouveau to Italy. In Vienna, “The Four” were given their own room “Saal X” in which they displayed about thirty pieces of applied and decorative arts together with furniture.24 It therefore shows a gap in the Biennale’s early strategy of innovation: perhaps the absence of a readily replicable display template coupled with the lack of experience in dealing with the decorative arts worked against the sheer aesthetic innovation brought from Scotland.

Both in 1897 and in 1899, rooms were carefully allocated to underline the importance of the sections shown. As indicated before, the Scottish painters were given Room R in 1897 therefore they were physically estranged from the rest of their British colleagues located in the adjacent Room P [fig. 2]. This is to be underlined as non-Italian sections were generally organised by nationality, a common labelling used at Universal Exhibitions as well. Furthermore, Room R was quite centrally placed, close to the central rotunda and more importantly close to the Head Office (Room Z) and Press Office (Room K).

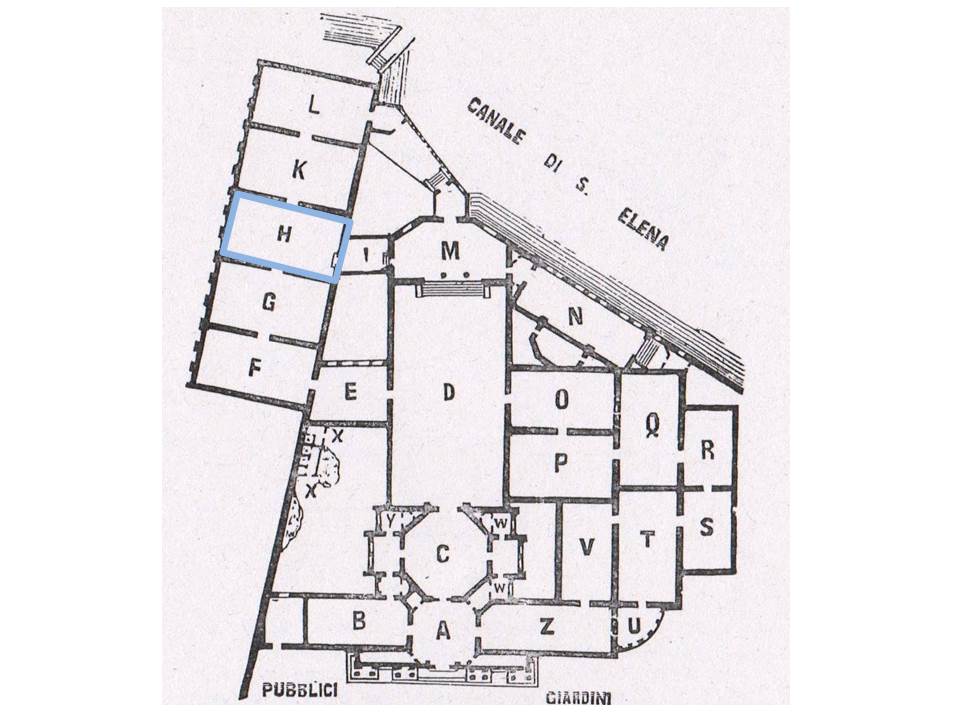

Such exclusive treatment seemed to have been prolonged in 1899 as Scottish painters were given again a “Scottish Room”, Room I, which contained sixty-one paintings [fig. 3]. Yet a closer look at the catalogue reveals that Thomas Austen Brown’s ceremonial ship launching was displayed in “the International Room D”, while a group of eight British works were added to Room I, thereby tempering the strong emphasis on regional identity displayed in 1897. Although some British works such as a pastoral landscape scene by Bertram Priestman (1868-1951), were aesthetically close to those of their Scottish peers as showing a mix of French and Dutch influences, others belonged to the classical tradition such as William Blake Richmond (1842-1921) who sent in his recently completed Maid of Athens. Room I, much like Room K which displayed both British and American works, therefore presented a hybrid content which belied the geographical label given to the room. In addition Room I was placed less favourably. From a central location, it moved to a peripheral one, at the top end of an enfilade of other national rooms. Access was therefore less easy and immediate. The examination of the 1901 Biennale map reveals that the Scottish section was fully subsumed in the British Room, located in Room H. The number of Scottish paintings presented was drastically reduced to twenty [fig. 4]. An acute shortage of space and the intense pressure to present new trends to the public therefore accounted for the move of Scottish paintings from centre to periphery, as prime physical space was given to other recent trends. Yet the number of sales show that taste for these poetic landscapes and portraits continued until circa 1910.

In 1899, the “Glasgow Style” was also given pride of place and the sheer innovative aspect of this section was emphasised through its central location in the international room M alongside Italian and international sculptures and other decorative works [fig. 3].25 The Biennale map shows that Room M was found at the end of the central gallery and would therefore invite a greater flow of visitors. It was accessed through a staircase from the central gallery, thereby positioning it as physically and perhaps metaphorically on a higher level. Yet as explained before, this display pointed to limits in the Biennale’s innovation strategy. Also, the marketing choice was less efficient inasmuch as it was not accompanied by explanatory notes in the catalogue. As underlined before, the sheer use of prime physical space was not sufficient enough to create a taste for the “Glasgow style” in Venice in 1899.

Fig. 4: Map of the Exhibition Palace [Pianta del Palazzo dell’Esposizione], 1901.

Reproduced in the Quarta esposizione internazionale d’arte della città di Venezia, Catalogo illustrato (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1901), unpaginated.

In addition to using the local and national press, Fradeletto also used internal communication channels, mainly the exhibition catalogue. Firstly “biographical notices” were published in the 1897 catalogue. They conveyed a two-fold aim: to help the Italian public become acquainted with international artists both reputable and less well-known, and to create a taste for them by showing their European reputation and their special links with Italy. For example, of Alexander Brown (1849-1922) it was written that “he exhibited at the Champ de Mars Salon; in Munich in 1893 he was awarded a medal for his painting The Gravelock which was then acquired by the Bavarian government. Some of his best paintings can now be admired in some German museums”.26 As to James Kerr-Lawson (1862-1939) the organisers chose to translate part of his letter: “We are now translating part of one his letters: “I was born in Anstruther, in the ancient Kingdom of Fife, the most beautiful part of Scotland… My masters have been and will always remain the great Italian painters, in particular the Venetian painters, who are incomparably the best of all”.27 In these couple sentences seemingly offered transparently to the Italian public, one could find a romantic evocation of a proud Scottish history; the firm allegiance of Scottish painters to Italy”s artistic domination and a flattering mention of Venetian painters. These marketing tools dwelling on special cultural and artistic bonds aiming at titillating the Italian public were used specifically for the Scottish painters, and they also helped them secure a market in Italy. Unfortunately in 1899, such “biographical notices” were altogether removed from the exhibition catalogue, which means that “The Four” did not benefit from the same amount of exposure in their introduction to the public.

Secondly, boundaries did not exist between “art” and the “market” as the Biennale both showcased and sold art until the 1970s. Indeed a report published in November 1896 not only gave a glowing introduction of the Scottish painters, but it also pushed forward their low prices: “A piece of information which will rejoice amateurs. Scottish paintings are moderately priced.”28 Both in 1897 and 1899, many Scottish artists found buyers in Venice: in 1897 they sold twenty paintings for a total of c.26,600 Italian lire (c. 1,064 pound sterling) which placed them in fourth position after Italy, Holland and Japan. An article dated 17 October 1897 confirmed that Scottish paintings were among the most attractive at the Biennale: “sales… in decreasing order: Italy, Holland, Japan, Scotland, Germany, Norway, Russia, France, England, Belgium, Denmark”.29 That year, 21 out of the 25 paintings sold in the British section were Scottish and the painter Robert Macaulay Stevenson sold four landscapes, i.e. as many as his English counterparts.

In 1899, the Scottish section sold 12 paintings but their overall sales volume remained satisfactory at c.24,000 Italian lire (960 pound sterling). All in all they fared much better than their English counterparts finding homes in a variety of public and private collections: official government and museum structures in Italy, the Italian Royal collection, the collection of the Prince of Liechtenstein, German dealer and adviser Ernst Seeger, or nouveaux-riches industrialists in Italy and abroad. The most famous collector who acquired Scottish art in Venice was Sergei Schshukin (1854-1936) from St Petersburg who chose James Paterson’s Enchanted Castle while his wife Lydia bought Macaulay Stevenson’s Soon as the Evening Shades Prevail.30

That year the “Glasgow Style” artists found one buyer at the Venice Biennale. Sicilian painter Ettore De Maria Bergler (1850-1938) acquired the two panels by the Macdonald sisters, The Annunciation and the Star of Bethlehem for a combined price of 600 Italian lire (24 pound sterling).31 A regular exhibitor at the Venice Biennale, De Maria Bergler was also a leading exponent of the Art Nouveau style. At the time he acquired the two Scottish panels in Venice, he was involved in the decoration of important public edifices, as for example the Teatro Massimo in Palermo or private villas such as Villa Igiea.32 This seems to confirm the impact of “The Four” in artistic circles, not only in Vienna, but also in Italy where the Stile Liberty fully blossomed after the 1902 Turin exhibition.

The introduction of Scottish artists in Venice in 1897 and in 1899 therefore provided a “wonderful revelation” for the Italian public. For the Venetian venture however, innovation was also a means to increase its “symbolic capital” as the expansion of “aesthetic culture” resulted in an accrued reputation. However the two waves of Scottish art introduced in the early years of the Biennale also show substantial differences of treatment. On the one hand, Scottish painting which already bore an international stamp of approval benefited from an array of marketing tools which promoted its easy identification and consumption. As a result many of the Scottish painters regularly participated to the Venetian exhibitions until 1910 while their works were regularly acquired in Venice. On the other hand, what now seems like an important aesthetic innovation, i.e. the first international group presentation of the “Glasgow Style”, was allocated prime physical space but not given as much coverage thereby resulting in a one-off participation. Comparisons with the 1900 Vienna exhibition and the 1902 Turin exhibition further underline the importance of display choices and Gesamtkunstwerk aesthetics to create a suitable environment for these works. Unfortunately this was not successfully implemented in Venice which pointed to the limits of their early exhibitions” strategy of innovation.

Marie Tavinor is Lecturer at Christie’s Education in London.

1 Gilberto Sécrétant, Il Salon veneziano, in Fanfulla della Domenica, 19/3, 17 January 1897, 2: “Come quella dell’ arte scozzese, il prossimo Salon veneziano prepara nuove, meravigliose rivelazioni agli artisti ed al pubblico d”Italia che si troveranno di fronte a intenzioni e concezioni d’arte nemmeno sospettate”.

2 Antonio Fradeletto, La gestione finanziaria delle esposizioni internazionali d”arte di Venezia. Relazioni e bilanci presentati dall”on. Antonio Fradeletto, Segretario generale, al Sindaco Co. Filippo Grimani, Presidente (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1908), 19.

3 Ibid., 19.

4 Venice, ASAC, Attività 1894-1944, Scatola Nera 7, Letter from Antonio Fradeletto to Alexander Robertson, 26 November 1896: “la scuola scozzese sarà una fra le maggiori attrattive della Mostra veneziana, tanto più che fin quà ha figurato in due sole Esposizioni del Continente: quella dei Secessionisti e quella del Glaspalast”.

5 Indeed in some instances when attempts were made to give more specific topographical indications, mistake were found: for example “Loch” was written “lock”, Seconda esposizione internazionale d”arte della città di Venezia, Catalogo illustrato (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1897), 192.

6 John Morrison, Holland and France: Prototype and Paradigm for Nineteenth-Century Scottish Art, in Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies, 2/1 (2008), 123-138.

7 George Mansell Rawson, Francis Henry Newbery and the Glasgow School of Art, Unpublished PhD dissertation, The University of Glasgow, 1996, 257.

8 A. Centelli, L”esposizione internazionale di Venezia II, in Fanfulla della Domenica, 19/23, 6 June 1897, 1.

9 Walter Shaw Sparrow, John Lavery and his Art (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner and Co ltd., 1911), 65.

10 Catalogo (1897), 80.

11 Vittorio Pica, I pittori scozzesi, in Marzocco, 2/16, 23 May 1897, 2. : “affinità di temperamento” “evidente omogeneita spirituale [ne]le loro opere”.

12 Sandra Berresford, The Pre-Raphaelites and their Followers at the International Exhibitions of Art in Venice, 1895-1905, in Sophie Bowness and Clive Phillpot, eds, Britain at the Venice Biennale, (London: the British Council, 1995) 37-49.

13 Kenneth McConkey, Rustic Naturalism at the Grosvenor Gallery, in Susan Casteras and Colleen Denney, eds, The Grosvenor Gallery, A Palace of Art in Victorian England (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 1996), 142.

14 Roger Billcliffe, The Glasgow Boys, the Glasgow School of Painting, 1875-1895 (London: John Murray, 1985), 294.

15 Marcia Pointon, “Voisins et Alliés: the French Critics” View of the English Contribution to the Beaux-Arts Section of the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855” in Saloni, Gallerie, Musei e Loro Influenze sullo Sviluppo dell’ arte dei secoli XIX e XX, ed. by F. Haskell (Bologna: CLUEB, 1981), 115-122.

16 Quoted in English in Charles M. Kurtz, A Collection of Paintings representing the Glasgow School, Artists of Denmark and Some Others (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1895), 12.

17 Venice, ASAC, Fondo storico, scatole nere 7, Pubblicità, Letter from Antonio Fradeletto a Pompeo Molmenti, 25 November 1896, 2.

18 Terza esposizione internazionale d”arte della città di Venezia, Catalogo illustrato (Venezia: Carlo Ferrari, 1899), 57-59.

19 https://www.moma.org/collection/works/4870, consulted on 2 April 2018.

20 Jude Burkhauser, T. Howarth ”Sala M” Arte Decorativa Scozzese: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow Group at the Venice Biennale Exhibition of 1899, in Charles Rennie Mackintosh Society Newsletter, 50 (Spring, 1992), 12.

21 Cristina Della Coletta, World’s Fairs Italian Style, The Great Exhibition in Turin and Their Narratives, 1860-1915 (Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2006).

22 Alfredo Melani, L”esposizione d”arte decorative odierna in Torino, V, Inghilterra e Scozia, in Arte Italiana decorativa e industriale, 9/8 (August 1902), 63-68. This article appeared in an anthology of critical texts on the Turin 1902 Exhibition: Torino 1902, polemiche in Italia sull’ Arte Nuova, ed. by Francesca R. Fratini (Torino: Martano, 1970), 216: “Voci isolate di lode e susurri estesi di sdegno. Ed io sentii allora dei decoratori italiani farsi beffe di certi pannelli scozzesi dello stesso genere di quelli che veggonsi oggi a Torino, farsi beffe delle loro figure lunghe, allampanate e stremenzite, e farne oggetto di dileggi grossolani.”

23 The International Exhibition of Modern Decorative Arts of Turin. The Scottish Section, in The Studio, 26/112 (July 1902), 92.

24 Katalog der VIII. Ausstellung der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Österreichs Secession (Wien: Adolf Holzhausen, 1900), 35-36.

25 Buckhauser, T. Howarth (Spring 1992), 12.

26 Catalogo (1897), 79: “espose al Salon du Champ de Mars; A Monaco nel “93 fu premiato e il suo quadro “The Gravelock” acquistato dal Governo bavarese. Le cose più elette di questo pittore si ammirano sparsamente nei Musei germanici”. Indeed Brown showed 6 paintings at the 1893 Glaspalast exhibition in Room 53 but the painting referred to in the Italian catalogue was actually entitled The Gareloch.

27 Catalogo (1897), 83.: “traduciamo da una sua lettera: “Nacqui ad Austruther, nell’ antico reame di Fifer, che è la contrada più bella della Scozia ... I miei maestri sono stati e saranno sempre i grandi pittori italiani, e massime i veneziani, che sono incomparabilmente maggiori di tutti”.

28 Venice, ASAC, Fondo storico, scatole nere 7, Pubblicità, Letter from Antonio Fradeletto a Pompeo Molmenti, 25 November 1896, 2. :”Una notizia che ricoglierà(?) gli amatori. I quadri scozzesi sono a mitissimo prezzo”.

29 Gilberto Sécrétant, “L”Esposizione a Venezia, prima della chiusura”, in Fanfulla della Domenica, 19/42, 17 October 1897, 3.: vendite... per la quantità in ordine descresciute: Italia, Olanda, Giappone, Scozia, Germania, Norvegia, Russia, Francia, Inghilterra, Belgio, Danimarca”. That newspaper article should be taken with a pinch of salt as it only represented a forecast of the sales given before the closure of the Biennale. A comparison between Sécrétant”s data with the ones in the ASAC registers reveal that his statement was as a result not entirely accurate: instead of the “circa 180” works sold, the register listed 239.

30 Venice, ASAC, Ufficio Vendite, Registro 2, IIa Esposizione della città di Venezia, 1897.

31 Venice, ASAC, Ufficio Vendite, Registro 3, 1899.

32 Cristina Costanzo, Ettore De Maria Bergler e le Arti Decorative: uno sguardo aggiornato attraverso la scoperta di fonti inedited, in Rivista dell’Osservatorio per le arti decorative in Italia, November 2014, DOI: 10.7431/RIV09112014, http://www1.unipa.it/oadi/oadiriv/?page_id=1968.