ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz

The trade in Far Eastern objects of art and consequently the establishment of an art market in Europe originated with the Dutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (V.O.C.) in the seventeenth century. In Berlin during the period from 1850 to 1870, East Asian art was often sold in conjunction with other goods from the Far East that were referred to as “colonial”, such as tea. At the turn of the twentieth century, the initially more popular Japanese art had passed its zenith in Germany, as elsewhere in Western countries, and interest gradually turned to Chinese art. Dealers began to adjust to the changes in taste, establishing galleries in boomtown Berlin which offered Chinese art, based on greater knowledge acquired on personal journeys to China. The article outlines the activities by four main Berlin dealers in Japanese and Chinese art: Theodor Bohlken, Edgar Worch, Otto Burchard and Felix Tikotin, before focusing on the highlights of the market turnover of Far Eastern art in Berlin’s boom years between 1927 and 1929.

In Germany the sale of Far Eastern goods picked up during the Gründerzeit era from circa 1850 to 1870. Import trading companies dealing in tea and other Kolonialwaren (goods from overseas) increasingly began to offer then-contemporary objects for interior decoration as well as older works of art from China and Japan as a side business. In Berlin, the most prominent of these companies was Rex & Co, founded in 1854, who offered East Asian art from the outset as part of their “colonial” product range. A dealer with an entirely different background was the publishing company R. Wagner, Kunst- und Verlagshandlung, who – although established in 1857 – only began to sell Japanese works of art and Japanese woodblock prints in the 1880s. The third noteworthy art dealer, the firm Alt-Japan- und China-Kunst Ernst Fritzsche, also came from the Kolonialwaren trade and founded his business in 1910. These three companies were the foremost Berlin dealers in Japanese and Chinese art before World War I.1

In the early 1900s Japonisme had passed its zenith in Germany, as elsewhere in Western countries, and interest gradually turned to Chinese art. On the one hand, the above-mentioned companies still catered to pre-war japanalia collectors, on the other hand they tried to adjust to the new taste for Chinese art. At the same time a new and younger generation of dealers who had spent years on the World War I battlefields, some of them discharged due to injuries, relocated to boomtown Berlin. They established galleries selling Chinese art, bringing with them the knowledge acquired on personal journeys to China, both fresher and deeper than the expertise of the old-generation owners of Rex, Wagner and Fritzsche.

This article will first briefly introduce four key dealers – Theodor Bohlken, Edgar Worch, Otto Burchard and Felix Tikotin, and then shed some light on the general turnover of Far Eastern art in Berlin in the boom years between 1927 and 1929.

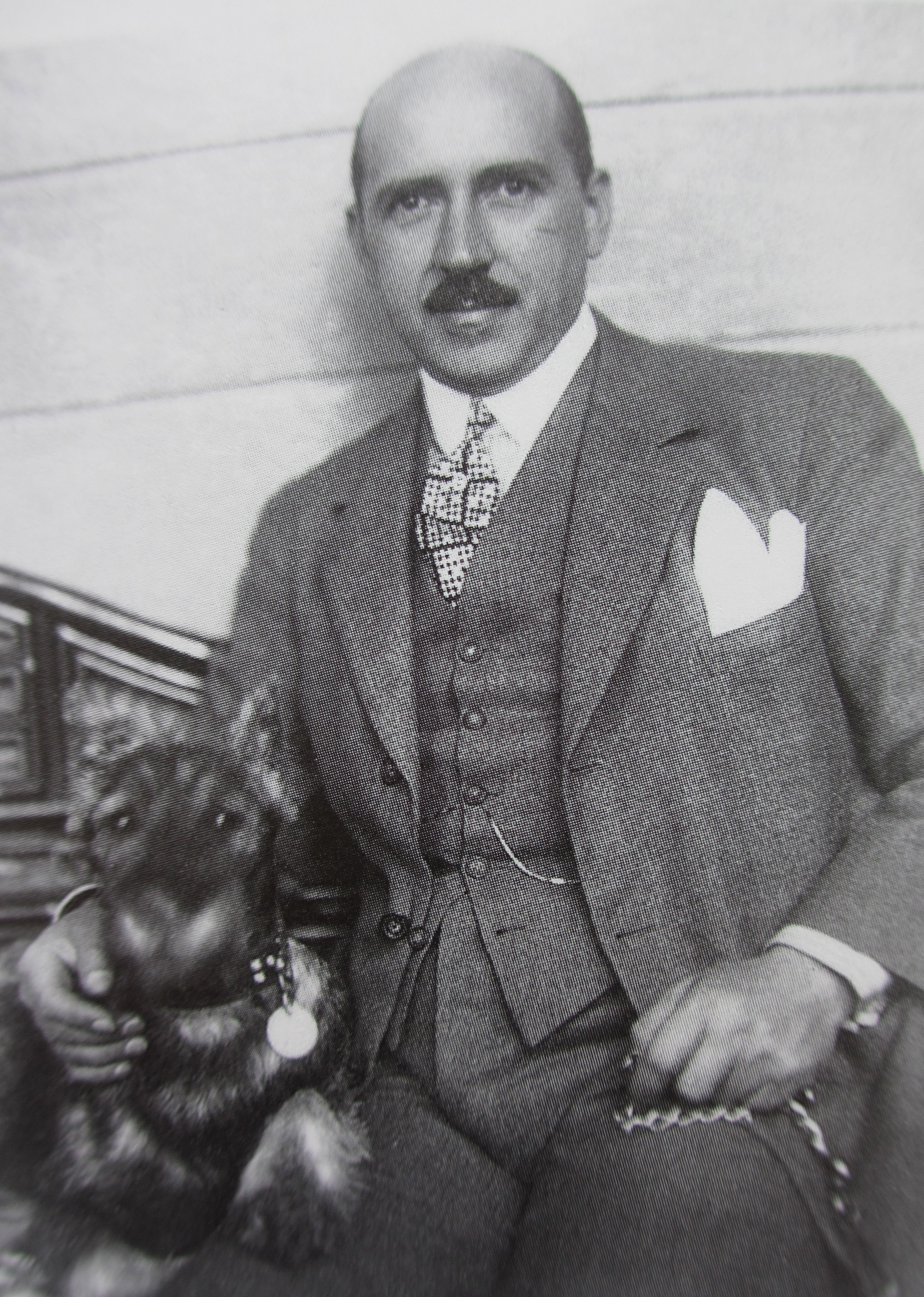

Theodor Bohlken trained as a merchant with Onno Behrends, a tea import company in East-Frisia in the north-western part of Lower Saxony (fig. 1). After World War I he moved to Berlin and opened his shop Theodor Bohlken. Import aus China und Japan on Kurfürstenstraße 122. While the business sold tea, he also offered works of art from China and Japan as documented by a small brochure, which contains short written introductions to various areas of Far Eastern art, several illustrations and a table of the Chinese dynasties and Japanese time periods. In these years — and certainly by 1925 — his buyer in China was Otto Burchard,3 later succeeded by Johann Janssen and Heinrich Peters who took turns travelling to China, and occasionally to Japan, once a year.

Fig. 1: Theodor Bohlken (1884-1954), circa 1926. Coll. of the author.

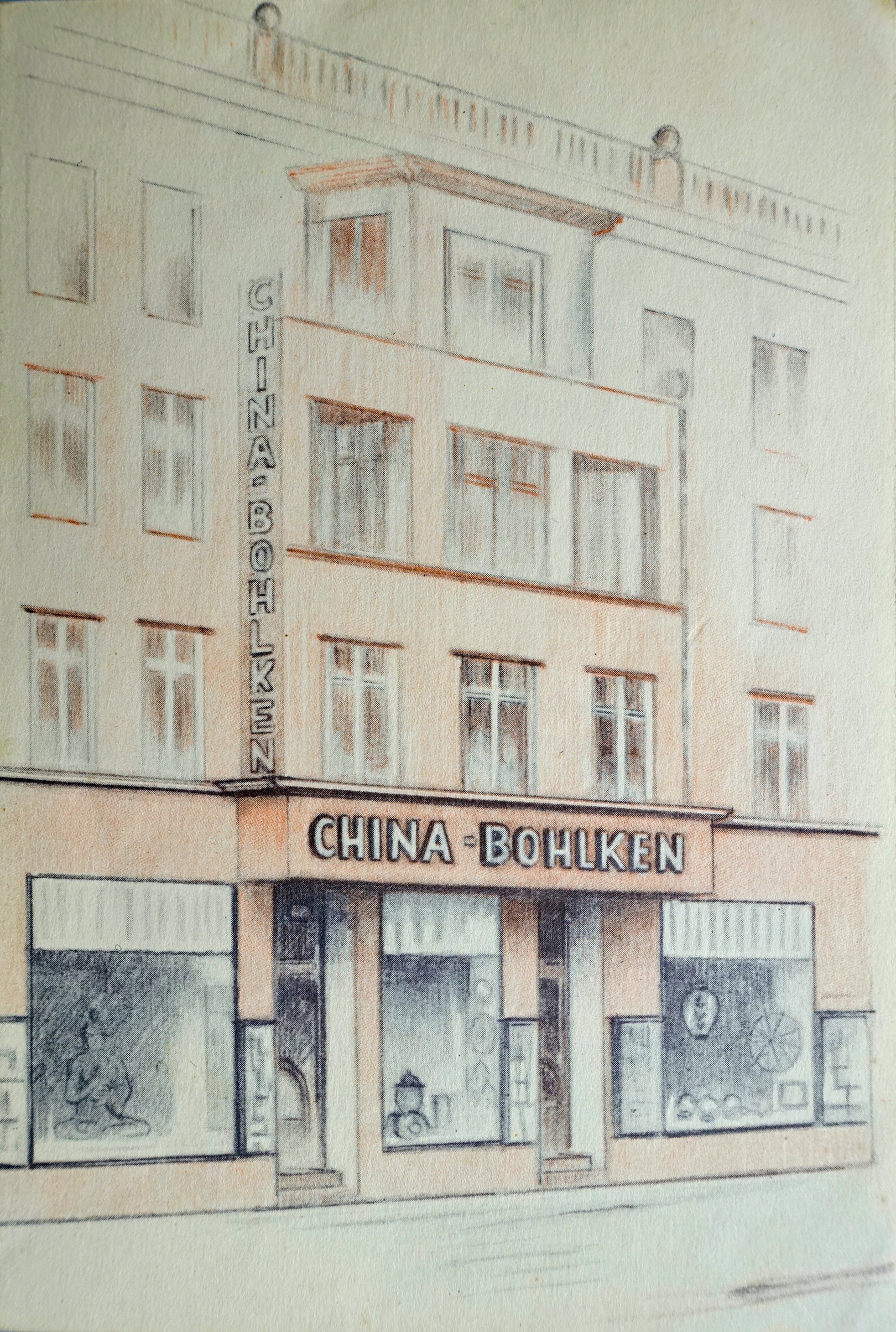

On 1 November 1927, now calling his shop China-Bohlken, he opened his gallery in a house on Potsdamer Straße 16 (fig. 2) where he had rented a large space covering four floors accessible by a lift. Probably on the occasion of the inauguration of the new premises he published an illustrated brochure giving us a vivid impression of the exhibition areas and the wide range of objects of artistic as well as decorative value.

Fig. 2: Flyer with the drawing of the gallery China-Bohlken, Potsdamer Straße 16, Berlin, ca. 1927. Coll. of the author.

While Bohlken sold tea and tea paraphernalia on the ground floor, the three floors above the teashop displayed Buddhist sculpture ranging from the Wei to the Ming dynasty, ceramics from China from the Han to the late Qing dynasty, Japanese works of art and interior decorations such as furniture, textiles and baskets. On the occasion of the groundbreaking exhibition of Chinese art held at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin in 1929 he published a small brochure on Chinese sculpture with an introduction by the well-known sinologist Ferdinand Lessing (1882-1961). Theodor Bohlken was most astute when it came to promote his business. He published brochures and placed regular advertisement in art magazines, with illustrations showing the wide range of objects on offer, sometimes combined with slogans full of Berlin-typical panache.

After twelve years on Potsdamer Straße the building was to be demolished to make room for Hitler’s projected monumental North-South axis.4 Bohlken continued his business until 1943 at new premises on Leipziger Straße 39. After World War II the long-time gallery branch in Westerland on the island of Sylt became the main location of the business, led first by himself and then by his daughter Ursula Zellermann (1921-2007).5

Theodor Bohlken’s clientele consisted of mostly local and national private collectors who visited the capital on business. In German museums, objects with a Bohlken provenance are rare. Karl With (1891-1980) bought several ceramics for the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Cologne, later transferred to the Museum of East Asian Art in the same city, while a handful of objects today in the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin were gifted. Conforming to contemporary taste for Chinese art, he primarily sold ceramics and Buddhist sculptures.

Edgar Worch (fig. 3) went to Paris in 1902 to start his career in the business of his uncle Adolphe Worch (1843-1915). Adolphe was the proprietor of the Compagnie commerciale de la Chine et du Japon on 9, rue Bleue, founded in 1888. Between 1906 and 1914 Edgar Worch travelled to China every year to buy works of art. Within his uncle’s company he built up a department of Chinese art resulting in the change of the business name into A. Worch. Antiquités de la Chine.7 A New York branch of the firm was set up in 1914, but the outbreak of World War I resulted in its closure just one year later. Nevertheless, highly important Chinese sculptures and archaic bronzes were sold to several major American museums in this brief period.8

Fig. 3: Edgar Worch (1880-1972), ca. 1940. From: Daniel Shapiro, Ancient Chinese Bronzes. A Personal Appreciation (London: Sylph Editions, 2013), 144.

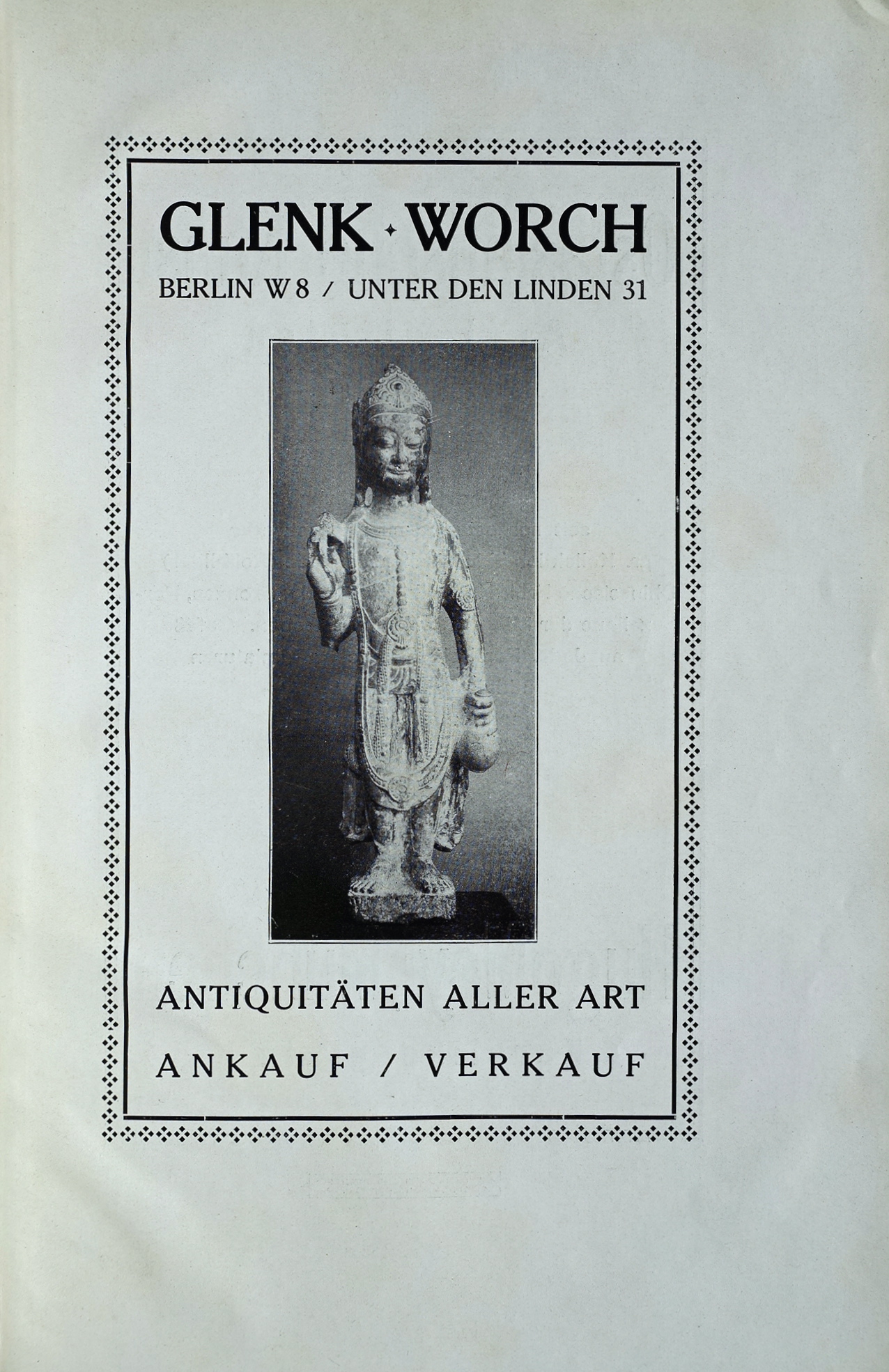

The inventory of the business A. Worch. Antiquités de la Chine in Paris was sequestered at the outbreak of World War I, due to Adolphe’s German heirs. Edgar Worch returned to Germany, where he was enlisted and subsequently discharged in 1917 after a serious knee injury. He settled in Berlin and became managing director of Ludwig Glenk, based at Unter den Linden 31, a company dealing in luxury goods and antiques of all sorts, including Chinese objects. In 1920 Worch became co-owner, gradually changing the company’s name into Glenk-Worch (fig. 4).

Fig. 4: Advertisement Glenk-Worch, showing the sandstone figure of a Guanyin, today in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst. From: Alfred Salmony, Chinesische Plastik (Berlin: Richard Carl Schmidt & Co., 1925), unpag.

We have no references about trips to China during these years, so Edgar Worch had to use every opportunity to replenish his stock of Chinese art. Two small but interesting business transactions are worth noting in this context. In the early 1920s, museums – not only in Berlin – began to sift through their inventories and sell selected pieces, either at auction or directly to private collectors or dealers. For example, Edgar Worch acquired a number of frescoes collected during the Turfan expeditions by Albert le Coq (1860-1930) from the Museum für Völkerkunde in Berlin in 1922 and 1923. Several of them were apparently quickly resold to Abel W. Bahr (1877-1959), who in turn passed them on to the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia in 1924.9 Also in 1922, Glenk-Worch acquired a number of Qing dynasty ceramics and porcelain snuff bottles formerly in the Max von Brandt collection in exchange for undisclosed objects.10

Another interesting, albeit not very well documented business relationship existed between Edgar Worch and Friedrich Perzyński (1877-1965). This extraordinary self-taught scholar of Japanese woodblock prints became famous for his book on Japanese nô masks. He travelled to China in 1912/1913 and returned to Germany with one complete figure of a glazed ceramic luohan and one bust fragment, both found in a cave near Yizhou, as well as two sandstone Guanyin sculptures.11 Prior to 1920, the Perzyński luohan bust was sold by Edgar Worch to the Frankfurt industrialist Harry Fuld (1879-1932).12 Perzyński was unable to sell the Buddhist sculpture of a Guanyin to Otto Kümmel, director of the Ostasiatische Kunstsammlung, in 1913.13 However, this same sculpture was sold to Kümmel by Glenk-Worch in 1924.14

Fig. 5: Monumental lion, China, Northern Henan, 2nd century AD, sandstone, length 135 cm, Paris, Musée Guimet. Photo by the author.

In the 1920s, high-end art dealers in Berlin increasingly settled in the Bellevuestraße and nearby. Edgar Worch followed this trend and moved his gallery to the prestigious Tiergartenstraße 2 in 1927. Newspapers reported on the new premises. As there are no photographs, I would like to quote a contemporary description of the interior:

The front rooms have the flair of distinguished Paris salons, with magnificent furniture and delightful porcelain, especially from Meissen. After passing through a corridor, the visitor finds himself surrounded by Chinese art. First, there is a room with solemn ritual statues from the early epochs, followed by room after room with cabinets full of the most precious creations of Eastern pottery art, from the discoveries in the tombs from the T’ang period to the exquisite masterpieces from the most important workshops of the Sung period. Finally, there are the unbelievably flawless porcelain pieces from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with a wealth in shape and richness of colour that could never be rivalled in Europe.15

It seems that the new gallery space mainly exhibited European works of art. Only two rooms were dedicated to Chinese art, one featuring archaic bronzes and the other Chinese ceramics. The showcases were fitted with interior lighting, and the floors were covered with Chinese carpets. The newspaper Deutsches Allgemeine Tageblatt of 19 June 1927 commented: “There is still a flavour of pre-war Berlin here – at the same time the opulence feels almost American”. Another article lists the object types: Jades, funerary and Buddhist sculpture, archaic bronzes, carpets and Chinese export porcelain.16

At Tiergartenstraße Edgar Worch operated under the name Edgar Worch, vormals Ludwig Glenk, Spezialität Alt-China, Direkter Import. Direct import was an internationally popular phrase in advertisements and letter headings of dealers in Chinese art. In Worch’s case, his brother-in-law Jörg Trübner (1901-1930) was in charge of purchases in China. While he was an academically trained student of Western art history, in China he could rely solely on his eye. He developed his expertise in the field by diligently describing his acquisitions and making drawings of them, by consulting Chinese experts, and by buying from renowned dealers such as Paul Hou Mingzi (1879-?) in Peking.17

On his third trip to China Jörg Trübner died of black measles. As a memorial to Edgar Worch’s promising and designated heir, Otto Kümmel published a volume presenting the important acquisitions made by Trübner. In the book, for each object sold the new owner is named, giving an overview of Worch’s clients in the years between 1927 and 1929.18 The arguably most outstanding work is the stone pagoda, which was acquired by Jörg Trübner but was sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art New York by C. T. Loo (1880-1957).

Highlights among the other objects sold by Worch in these years were a life-size wood figure of a Guanyin today on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, a stone lion today in the Musée Guimet in Paris, and two celadon candle holders, one today in Museum of Greater Victoria, Victoria, Australia and the other with Maria Kang, Hong Kong.

Despite the evolving world economic crisis Worch mounted an exhibition of Chinese art at the Fifty-Sixth Street Galleries in New York City in 1930, accompanied by a catalogue with a post-scriptum by Otto Kümmel. Sales from this exhibition included a stele of two bodhisattvas to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a large famille verte charger to John D. Rockefeller Jr.19

The untimely death of Jörg Trübner, the economic crisis and perhaps also the rise of National Socialism most likely all contributed to Edgar Worch’s decision to close the Tiergartenstraße gallery and move his trade to his private home on Nussbaumallee 18-20 in Berlin-Westend. No major activities are recorded until a sale of minor works of art at Paul Graupe’s auction house in May 1935 in conjunction with Worch’s imminent emigration via Switzerland and Paris to New York, where he settled in 1939.

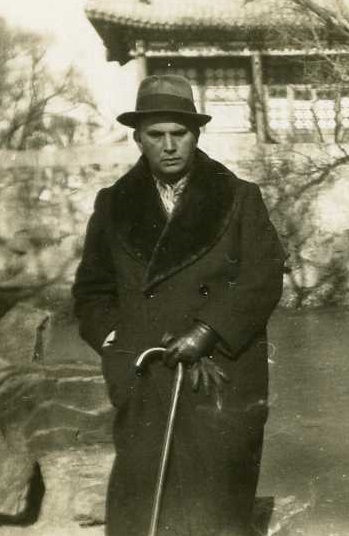

Otto Burchard’s early days as an art dealer differed considerably from the professional beginnings of Theodor Bohlken and Edgar Worch (fig. 6) He studied sinology at the university of Leipzig, finishing his studies with a thesis on Chinese painting, while otherwise making a name for himself as a writer.

After his discharge from the German military as permanently disabled in 1916, Otto Burchard moved to Berlin in 1917 where he opened an art gallery on Lützowufer 13 in 1920. He came to fame as the host of the most prominent event of the avant-garde Berlin Dada movement, the International Dada fair which ran from 30 June to 25 August 1920. He was duly honoured with the grand title of “Generaldada, Exzellenz”. On 1 June 1921 the modern art dealer Alfred Flechtheim took over the premises, and Otto Burchard disappeared from the public eye.

However, he continued to pursue his passion for Chinese art, which had first developed in the 1910s, and he published three small books on Chinese bronzes and ceramics in 1922 and 1923. During these years he travelled regularly to China as a buyer for Theodor Bohlken, and according to his own statement he held shares in the latter’s company.21 In the meantime he assembled his private collection of Chinese art, which was shown from October 1924 onwards in one room of the newly opened galleries of the Ostasiatische Kunstsammlung (Far Eastern art collection) in the Museum in der Prinz-Albrecht-Straße, today known as the Martin-Gropius-Bau.22

Fig. 6: Otto Burchard (1892-1965) in Peking, 1931. Photo: Family archive.

The name of Otto Burchard officially reappeared in the art trade again when he joined the Margraf group, a conglomerate which included dealers in old master paintings, in European silver and in decorative arts. In late May 1927 the company Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH opened on the belle étage of a fin-de siècle villa in Bellevuestraße 11a, next door to the famous Café Schottenhaml. The six spacious rooms were refurbished by Franz Lissa and furnished with built-in showcases. They displayed large sculptures of wood and stone and ceramics of the Tang and Song dynasties, archaic bronze vessels, and bronze fittings of the Siberian nomadic tribes.

Fig. 7: Advertisement. From: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Folge, vol.7 , no. 5 (1931), back inside cover, U III

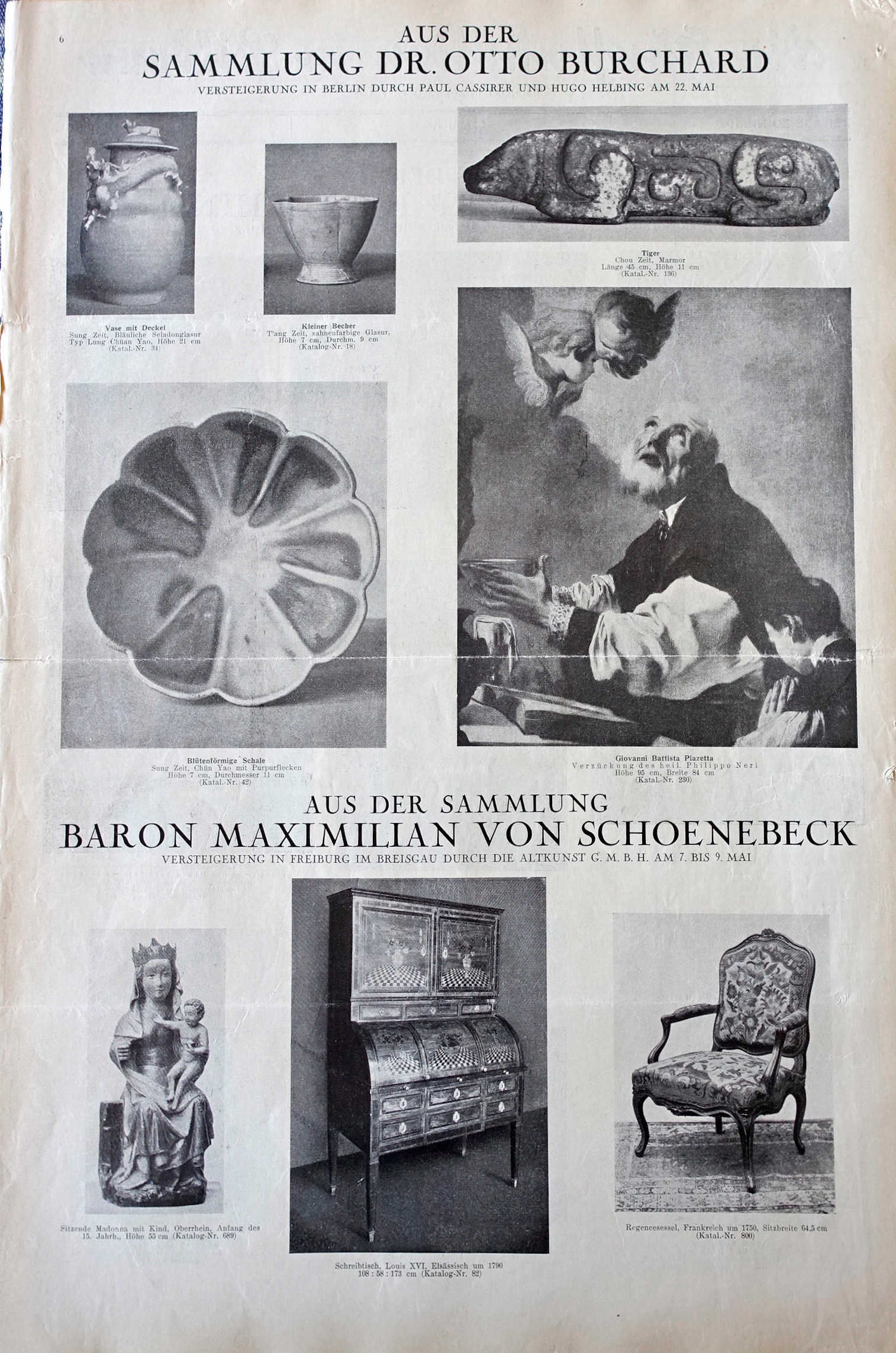

The following year – 1928 – was marked by a flurry of activities starting in January with a second exhibition of new acquisitions. This show received various reviews, the most detailed one by Leonhard Adam (1891-1960), who mentioned archaic bronzes, large sculptures and Tibetan Buddhist bronzes and thangka, then a novelty on the Berlin art market. He also commented on the large and impressive size of many art objects.23 Some of the prices he charged are recorded in the notes on inventory cards held at the Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich.24 In April and May of the same year an exhibition of Chinese painting took place at the premises of the art dealer and auctioneer Paul Cassirer on Viktoriastraße 35, around the corner of Bellevuestraße. The exhibition previously shown in Düsseldorf at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen was accompanied by a catalogue written by Otto Kümmel. The sale of Otto Burchard’s private collection through Cassirer & Helbing followed in May, to which we will return below.

Fig. 8: Advertisement for the auction Dr. Otto Burchard showing three Chinese ceramics acquired by Alfred Schoenlicht (?-1955). From: Die Kunstauktion, vol. 2, no. 19 (6 May 1928), 6.

Ever since the gallery’s opening the company name Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH included the sub-heading Berlin-Shanghai-Peking, implying addresses or offices in China. A company branch opened in New York in 1929 (fig. 7), which existed until 1931 and successfully sold to museums in Detroit and Boston.25

In 1932 Otto Burchard and his wife relocated to Peking where he became known as a connoisseur of considerable reputation. From here he supplied his nephew Wolfgang Burchard with stock, who had opened a Berlin gallery for Chinese art at Viktoriastraße in 1933.26 In 1935 the firm Dr Otto Burchard & Co GmbH was liquidated, and the inventory was sold at two auctions at Paul Graupe’s (fig. 8). Otto Burchard and his wife continued to live in China until 1946, when they settled first in New York and later in Jegenstorf near Bern in Switzerland.

While Felix Tikotin was by no means as important a figure as the three preceding art dealers and worked from a comparatively tiny space in the back wing of an impressive fin-de-siècle apartment compound on Kurfürstendamm, he nevertheless occupies a special position as the only dealer specialising in Japanese art in the Weimar Republic.

Felix Tikotin was born in Glogau, Silesia, and came to Dresden as a child with his parents in 1904. He studied to become an architect but his passion for Japanese colour woodblock prints led him to set up a Kunstkabinett. In 1927 he moved to Berlin and opened a gallery with an exhibition of woodblock prints and books featuring ghosts, which appropriately took place at midnight. Rumour had it that at the opening guests were given candles to inspect the prints by the flickering light of the flames, which would be entirely in keeping with the flamboyance of Berlin in the Roaring Twenties.

Fig. 9: Felix Tikotin (1893-1986) with Nathan Israel (left) and William Cohn (right) in front of the house on Kurfürstendamm 14/15. Estate of Felix Tikotin, Amsterdam.

Tikotin was extremely versatile and a resourceful networker who bought whole collections and travelled to auctions in Paris and London from early on. In 1927, 1928 and 1930 he went to Japan not just to buy prints and works of art but also to sell Japanese ukiyo-e to Japanese dealers. His numerous exhibitions were all accompanied by flyers, brochures or catalogues, written by his friend the Japanologist and woodblock print expert Fritz Rumpf (1888-1949).28 Tikotin’s clients were German private collectors, but he also sold several Japanese prints to the Kunstbibliothek in Berlin, whose collection of Far Eastern prints and paintings was turned over to the war-depleted Museum of Far Eastern Art in 1967. Felix Tikotin emigrated to Holland in early 1933 and settled in Switzerland in 1960. His passion for dealing in Japanese art remained undiminished for as long as he lived.

As the economy picked up again in the aftermath of the hyper-inflation of 1922/1923, the Berlin trade in Far Eastern art entered an unprecedented boom phase. The year 1927 saw the opening of three galleries (Worch, Burchard and Tikotin), while Theodor Bohlken moved from small premises into a multi-storied house at the heart of the Berlin art market (fig. 9).

Interest in Far Eastern art and appreciation of Chinese art by German collectors and the Berlin high-society was never as wide-spread as during the 1920s. This is mirrored in daily newspapers as well as weekly and monthly art magazines where exhibitions of new acquisitions of the above-mentioned dealers were reviewed regularly.29 Numerous and regular advertisements placed by these and other dealers specialising in this field were a recurrent feature in the issues of the weekly magazine Die Kunstauktion, launched in 1927 and renamed Die Weltkunst in 1930.

Photographs by Martha Huth, Waldemar Tietzenthaler and others featuring private homes in interior decoration and architectural magazines as well as the illustrations of home stories in lady’s and various other magazines attest to the ubiquity of Chinese works of art on shelves, cupboards, pedestals, walls and gardens. In these pictures we find Tang horses, Han figurines, mounted heads of a Buddha or Bodhisattva, Song dynasty bowls and dishes, Chinese porcelains as well as paintings, usually cut out from the mounting and framed.

Fig. 10: Brochure “China Bohlken”, ca. 1927. Coll. of the author.

These works of art may well have been purchased from the above-mentioned dealers but also at auction. Berlin boasted of a number of auction houses, the most famous one being Cassirer & Helbing. This firm held single-owner sales of no less than eight important Berlin-based collections of Chinese and Japanese art within four years (fig. 11).30

The most spectacular auction was the 1928 Cassirer & Helbing sale of the Tony Straus-Negbaur (1859-1942) collection of Japanese woodblock prints with a sale total of 220,000 mark (the equivalent of 748,000 euros today). The audience in the saleroom was international. A newspaper article mentions a Japanese dealer by the name of Murakami,31 while important prints were sold to Americans such as Louis V. Ledoux and Howard Mansfield and to bidders from Paris. Among the German buyers, Felix Tikotin paid the highest prices.32 A print of three beauties by Utamaro was the most coveted lot, with a spectacular hammer price of 6,500 mark. Nevertheless, this was a relatively moderate price, considering that Albrecht Dürer’s famous print Adam and Eve – in my view, of comparable art historical standing – had been sold at auction for 46,000 mark at C. G. Boerner in Leipzig the year before.33

Despite the hype for Chinese art, the auction result of Otto Burchard’s private collection (208 lots of Chinese art and 61 European works of art) must be regarded as a disappointment, achieving a mere total of 100,000 mark (today 340,000 euros). The reserves were much lower than the estimates and the hammer prices usually ranged slightly above the reserve. The most important bidder at this sale was the Dutch banker Alfred Schoenlicht (1876-1955), whose purchases included the three most expensive ceramics pieces, followed by the violinist Bronisław Hubermann (1882-1947), who bought sculptures and ceramics, and the Berlin collector of ceramics and Ordos bronzes, the socialite Edith Rosenheim (1896-1965).34

The Breuer sale at Cassirer & Helbing in May 1929 realized 146,000 mark with a disappointing 55% sold by lot. The physician Dr Adam August Breuer (1868-1944) was a distinguished long-time collector of Chinese lacquer, Japanese sculpture and paintings. In his auction review, Otto Kümmel expresses his disappointment and blames the pending economic problems and the precarious political situation for the meagre success of this sale.35 The highlight of the auction was the Japanese hanging scroll of Bodhisattva Jizô which was bought by the Dutch Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (Society of the friends of Asian art) for the mere sum of 20,500 mark. Today it is preserved at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Generally speaking, Chinese ceramics were the most popular genre with Berlin collectors of the years from 1927 to 1929. The shapes of Song dynasty dishes appealed to modernist tastes influenced by the aesthetics of the Bauhaus. At auction they sold for relatively high prices, as the example of a junyao bowl with a hammer price of 5,500 mark demonstrates, which was sold to Schoenlicht at the Burchard sale. Then again, Edgar Worch paid 6,000 mark for a pair of clay circus riders at the Theodor Simon sale in 1929.

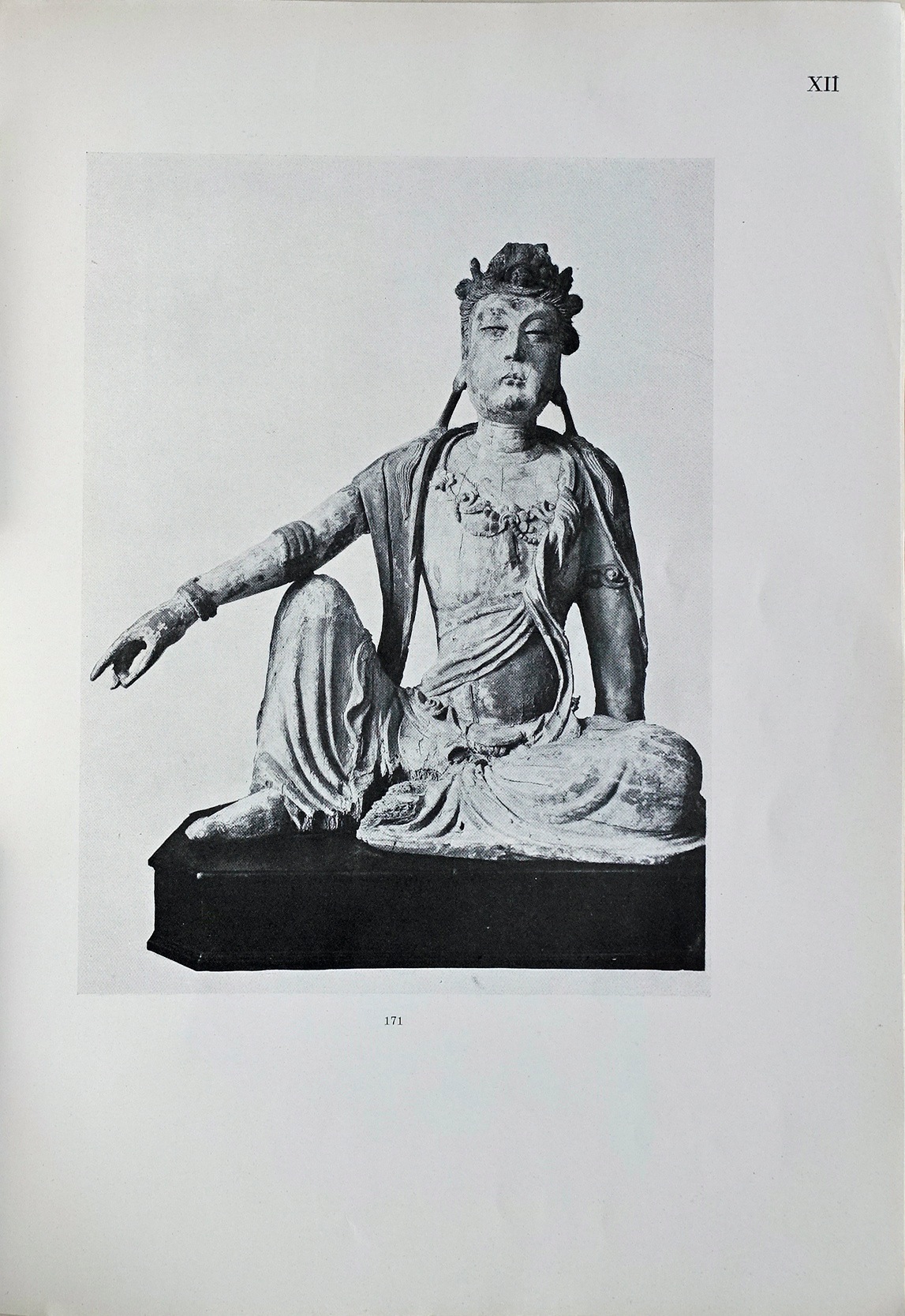

Next in popularity were Buddhist sculptures made of stone or wood. While they were of impressive size and highly decorative, their auction prices nevertheless did not exceed 4,300 mark. For instance, 4,000 mark were paid by Karl Haniel (1877-1944) in 1928 for a wooden Bodhisattva from the stock of Edgar Gutmann, today in the Museum Rietberg in Zürich.

Fig. 11: Guanyin, China, Song dynasty, 12th century, wood, height 90 cm. From: Besitz des Herrn Edgar Gutman/Berlin (Berlin: Cassirer & Helbing, 23 March 1928), lot 171.

The pinnacle of the China hype was the 1929 exhibition of Chinese art held in Berlin at the Akademie der Künste. The show displayed the whole spectrum of Chinese artistic production, with various objects lent by private collectors, museums and dealers predominantly from Berlin. The list of lenders is a who-is-who of German private collectors, while the number of objects lent by individual dealers suggests a ranking by the show’s academic organisers. Worch was the best represented with thirty objects, followed by Burchard with eleven and Bohlken with five objects, while Tikotin brought up the rear with two ceramics. Worch was obviously also favoured by the weekly magazine Die Kunstauktion, which published an article on his gallery on 8 January 1929 with a large number of illustrations from his stock.

It is difficult to explain the discrepancy between the slack auction sales and the activities of the dealers and the abundant presence of Chinese art in the media at the time. Edgar Worch and Otto Burchard offered the highest quality. While standing in the shadow of international mega-dealers such as C. T. Loo & Co (Paris/New York) and Yamanaka & Co (Osaka/Kyoto/New York/Boston/London), their connoisseurship, business acumen and good eye elevated them to global players. After the death of Jörg Trübner, Edgar Worch’s designated successor, in 1930 and after Otto Burchard’s eventual relocation to Peking in 1932 the trade in high-quality Chinese art disappeared as quickly as it had surfaced.

Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz is the editor of Ostasiatische Zeitschrift and has published widely on Japanese art and the German art market.

1 Rex & Co. was listed in the Berlin telephone directory until 1922 (at Mohrenstraße 7-8); R. Wagner was last listed in 1932 (at Potsdamer Straße 134).

2 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Vom Tee zur Kunst, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie, no. 17 (Spring 2009), 31-45.

3 SMB-ZA (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv), I/MfV, OAK 5, 54.

4 The grandiose plan was for a wide road leading from a new gigantic railway station in the North and a “Great Hall” to an equivalent Southern railway station.

5 This branch was one of several and had existed at least since 1927.

6 Information on Edgar Worch can be gleaned only through a considerable amount of short comments, half sentences etc. in sources too numerous to be cited here. The main article on Worch was published by Walter Bondy, Edgar Worch, in Die Kunstauktion, vol. III, no. 1 (8 January 1929), 9. On later developments see: Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Ostasiatika-Händler in Berlin von 1933-1945, in Bianca Welzing-Bräutigam, ed., Spurensuche. Der Berliner Kunsthandel 1933-1945 im Spiegel der Forschung (Berlin: be.bra wissenschaft verlag, 2018), 63. For details about post-war restitution claims in this complex case, see the file in the Landesarchiv Berlin (B Rep. 025-06 Nr. 5831/59).

7 Éric Lefebvre, Le destin des collections d’art chinois d’un marchand d’antiquités allemand de Paris: Adolphe Worch (1843-1915), in Marie Dollé and Geneviève Espagne, eds., Idées de la Chine au XIXe siècle: Entre France et Allemagne (Paris: Les Indes savantes, 2014), 221-233.

8 Institutions included the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, and the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia.

9 Miki Morita, The Kizil Pantings in the Metropolitan Museum, in Metropolitan Museum Journal 50 (2015), 114-135, 129.

10 See for example the accession ledger (Eingangsbuch) for 1879 of the Kunstgewerbemuseum, 267.

11 Friedrich Perzyński, Von Chinas Göttern. Reisen in China (München: Kurt Wolf Verlag, 1920). Plates 22 and 31 show two stone figures of Guanyin with the source indication “Im Besitz des Verfassers” (owned by the author). The Yizhou luohan on plates 42 and 43, today in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (acc. no. 20.114), was sold to the museum directly by Perzyński in 1920.

12 The sale of the luohan bust by Worch is referred to in a letter from Otto Burchard to his brother Ludwig, dated 10 May 1935. Family archive Alan Burchard.

13 SMB-ZA,I/MfV, OAK 4, 274.

14 SMB-ZA,I/MfV, OAK 4, 276.

15 “So tragen die vorderen Räume den Charakter vornehmer Pariser Salons mit prachtvollen Möbeln und mit herrlichen Porzellanen, vor allem Meißner Herkunft. Man durchschreitet einen Korridor, und man ist von der Kunst Chinas umgeben. Ein Raum mit feierlichen Kultstatuen der frühen Epochen macht den beginn, und nun schließt sich Raum an Raum mit Vitrinen voll der kostbarsten Erzeugnisse östlicher Töpferkunst von den Gräberfunden der T’ang-Zeit zu den erlesenen Schöpfungen der Hauptwerkstätten der Sung-Zeit. Und bis zu den unbegreiflich vollendeten Porzellanen des 17. und 18. Jahrhunderts, deren Formenreichtum und Farbenglanz in Europa niemals erreicht worden ist.” Curt Glaser, Zwei neue Kunsthandlungen. Heinrich Thannhauser – Edgar Worch, in Berliner Börsen-Courier, no. 290 (24 June 1927), 2.

16 Alfred Salmony, Ostasiatische Kunst am Berliner Markt, in Cicerone (1927), 535.

17 The wood figure of a life-size Guanyin mentioned below must have been bought from this Peking dealer as it is published in Paul Houo-Ming-Tse, Preuve des Antiquités, Peking 1930, 299, a compendium of objects sold and offered by his shop named Ta-Kou-Tchai.

18 Among them, the following names of German collectors living in Berlin are listed: Heinrich Hardt, Herbert von Klemperer, Fritz Kreisler, Jakob Goldschmidt, Richard Weismann. International collectors include the Comtesse de Béhague, Michel Calmann and David David-Weill in Paris, Adolphe Stoclet in Brussels, the Vereniging van Vrienden der Aziatische Kunst (Society of the friends of Asian art), van der Mandele und G. A. Voûte in The Netherlands, and John Gellatly, Christian R. Holmes, Otto Kahn and Grenville L. Winthrop in New York. Otto Kümmel, Jörg Trübner zum Gedächtnis. Ergebnisse seiner letzten chinesischen Reisen (Berlin: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1930).

19 Sold at Christie’s, Hong Kong, The Imperial Sale, Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, 27 May 2009, lot 1872.

20 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Otto Burchard (1892-1965). Vom Finanz-Dada zum Grandseigneur des Pekinger Kunsthandels, in Deutsche Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst Mitteilungen, no. 12 (June 1995), 23-35.

21 Last will (letter dated 23 September 1925), SMB-ZA,I/MfV, OAK 5, 54.

22 Adam August Breuer, Die Sammlung Dr. O. Burchard, Leihausstellung derselben im Berliner Ostasiatischen Museum, in Jahrbuch der Asiatischen Kunst, vol, 2 (1925), 13-22.

23 Leonhard Adam, Neuerwerbungen aus China, in Cicerone, vol. 20, no. 5 (1928), 167-170.

24 See article by Ilse von zur Mühlen in this issue, DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i3.75.

25 Die Weltkunst, vol. 5, no. 4 ( 25 January 1931), 3.

26 See advertisement “Burchard Alt-China” in Die Weltkunst, 15 October 1933, vol. 7, no. 49 (3 December 1933), 4.

27 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Felix Tikotin’s early years in Germany, in Jaron Borensztajn, ed., Ghost and Spirits from the Tikotin Museum of Japanese Art (Leiden: Leiden Publications, 2012), 44-61.

28 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Ausstellungen bei Tikotin, von 1927 bis 1932, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Serie, no. 22 (Autumn 2011), 30-36.

29 Curt Glaser wrote regular reports on gallery openings for the daily Berliner Börsen-Courier, while Alfred Salmony (1890-1958) and Leonhard Adam wrote gallery exhibition reviews for the art magazine Cicerone.

30 Between 1926 and 1929 the following collections of Far Eastern art came up for sale at Cassirer & Helbing in Berlin: Franz Lissa on 28 April 1926, Walter Bondy on 18/19 May 1927, Edgar Gutmann on 29 March 1928, Dr. Otto Burchard on 22 May 1928, Tony Straus-Negbaur on 5/6 May 1928, Dr. A. Breuer on 14/15 May 1929, Dr. Friedrich Perzyński on 15 May 1929 and Theodor Simon on 5 November 1929. See also the article by Britta Bommert on auction sales for East Asian art in German-speaking countries in this issue.

31 Undated newspaper clipping entitled “Drei Erdteile kaufen” without mention of the newspaper’s name, enclosed in the copy of the Tony Straus-Negbauer auction catalogue kept in the library of the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst in Cologne.

32 Der Kunstmarkt, vol. 2, no. 24 (10 June 1920), 2.

33 Alfred Kuhn, Rückblick auf das Kunstjahr 1927, in Die Kunstauktion, vol. 2, no. 1 (1 January 1928), 1.

34 Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Folge, vol. 4, no. 3 (1927/1928), 174.

35 Otto Kümmel, Deutsche und Japanische Versteigerungen, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Folge, vol.5, no.3 (1929), 103-104.