ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Akiko Takesue

This article examines the ways how the formation of the Japanese ceramic collection of Sir William Van Horne (1843-1915) in Montreal was informed by art dealers and the global market of Japanese ceramics in the late 19th to early 20th century. Van Horne’s dealers, based in Japan and the US, played a significant role in the way Van Horne collected and perceived Japanese ceramics, because Van Horne never went to Japan and acquired objects only from them. Van Horne’s decisions about what to collect were not simply determined by his own judgment, but were also affected by external factors such as the availability of Japanese objects in the Western market at the time, and the intellectual landscape and the broad trends within the Euro-American circle of collecting Japanese ceramics. Furthermore, these currents in “collecting Japan” themselves did not occur naturally: they were in fact informed by the intentions, concerns and desires of influential dealers, collectors, and scholars. When looking at the establishment of a collection not only from the collector’s taste, but also from these external factors, a collection can be understood as a complex space in which multiple subjectivities and economies are intertwined.

This article examines how the Japanese ceramic collection of Sir William Cornelius Van Horne (1843–1915) (fig. 1) in Montreal was shaped by art dealers and the global market of Japanese ceramics in the late nineteenth to early twentieth centuries. Because Van Horne acquired objects only through dealers based in Japan and the US, rather than by visiting Japan, they played a significant role in the way he collected and perceived Japanese ceramics. Van Horne’s decisions about what to collect were not determined simply by his own judgment, but also by external factors such as the availability of Japanese objects in the Western market and broader intellectual trends among contemporary collectors of Japanese ceramics in the West. These currents did not occur naturally but were informed by the intentions, concerns, and desires of influential dealers, collectors, and scholars.

Fig. 1: Sir William Cornelius Van Horne (1843 – 1915), date unknown.

W.A.Cooper / Library and Archives Canada / PA-182603

Recent studies of collecting tend to interpret the motives of individual collectors from the standpoint of their self-identity. In particular, collections of non-Western objects in the nineteenth-century West are viewed as a reflection of colonial ideologies, including Orientalism, that manifest the subject’s identity, desire, and domination. Through this lens, collecting is understood as a rational and objective act, one that seeks to exercise control over cultures of the Other.1 However, this approach considerably reduces the complex and contingent nature of a collector’s motive and the actual process of establishing the collection. The notion of identity is itself highly ambiguous and ever-shifting. More importantly, however, the process of acquiring objects is shaped not only by the collector’s personal views and tastes, but also by various external factors such as market trends, availability, dealers’ marketing strategies, access to the latest knowledge on the objects, opinions and advice from dealers and fellow enthusiasts, and personal and financial situations. These factors are in turn informed by broader socio-political and economic environments in which the collecting process is embedded, as I shall argue.

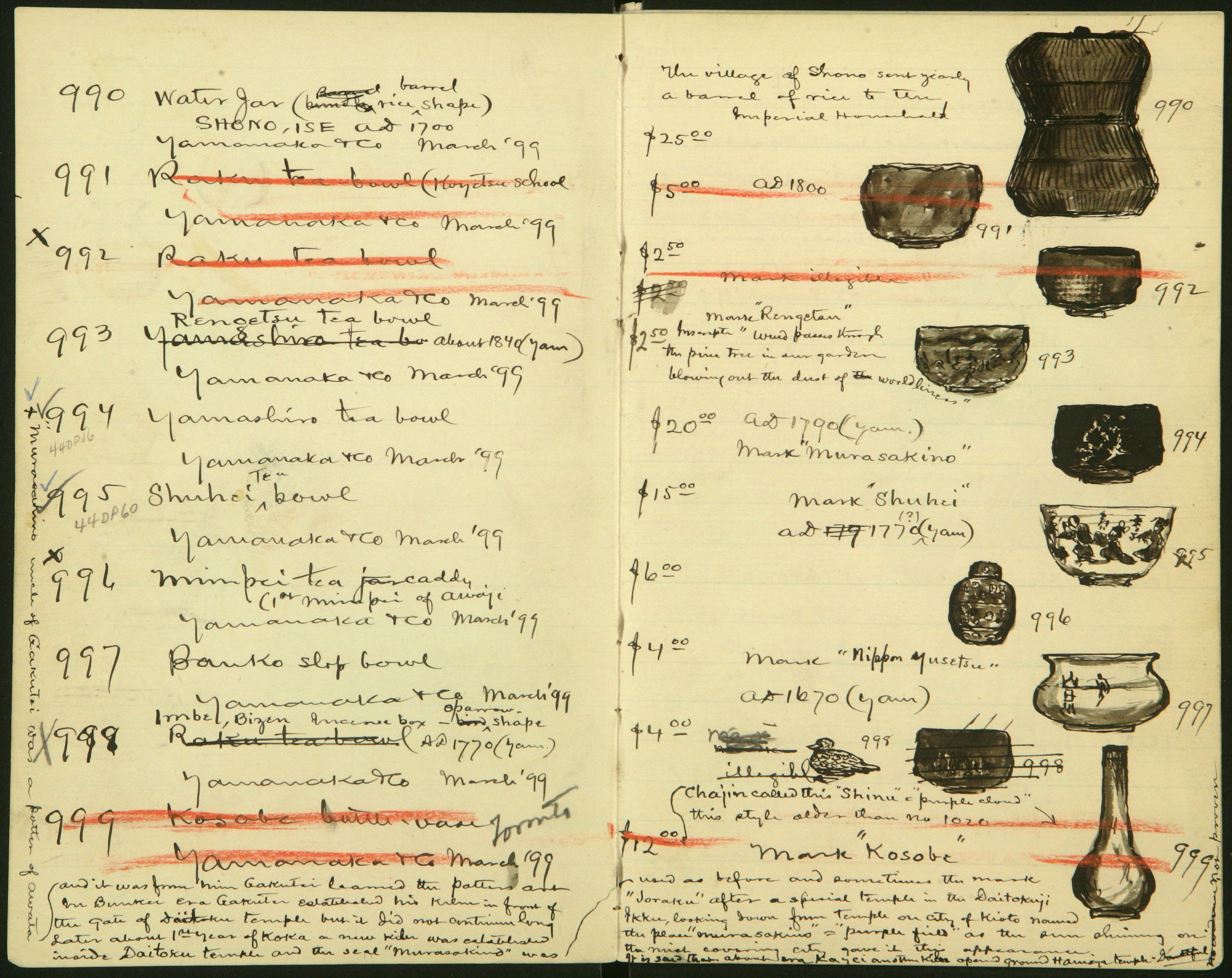

Van Horne was born in the United States but worked as an official with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) and lived in Montreal from 1883 to 1915.2 In addition to a large collection of European and American paintings, decorative arts, and Persian rugs, he amassed a Japanese ceramics collection of approximately 1,200 objects that primarily included unassuming stoneware of tea bowls, sake bottles, and other utilitarian objects produced for the Japanese domestic market (fig. 2).3 It was one of the largest collections of its kind in North America during his time, as well as one of the earliest ones that went beyond decorative ceramics exclusively made for the Western market since the mid-nineteenth century. Van Horne was more interested in the taxonomic aspect of collecting than the aesthetic quality of individual objects and therefore devoted himself to studying and identifying which maker or kiln had created each piece. From 1893, he meticulously recorded every acquisition in multi-volume catalogues that were written and illustrated by hand (figs. 3 and 4).4 These catalogues were organized according to his own numbering system, usually based on the acquisition date.5 A typical entry includes the Van Horne inventory number, a brief description of the object, who he bought it from and when, cost, and a small illustration drawn in black and white or in colour. Van Horne frequently updated descriptions with comments from his dealers and fellow collectors including Edward E. Morse (1838–1925) and Charles Lang Freer (1855–1919), demonstrating his enthusiasm for the discovery of new information.

Fig. 2: Portrait: Interior of Van Horne's Residence (office), date unknown.

Sir William Van Horne Fonds. Library and Archive Canada. e003641851

Art dealers supplied Van Horne with both objects and information about them. During the nascence of Japanese ceramic collecting in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when resources of information were highly restricted, dealers played a significant role in making and disseminating knowledge of Japanese ceramics based on the objects they stocked. In other words, the availability of works of art shapes knowledge of art, as Richard Wilson argues.6 Some dealers had a stronger impact on the Van Horne collection than others. While specific client-dealer relationships would have evolved naturally from their personal connections, one dealer’s merchandise was more favourable to Van Horne than others’; shifts in their marketing strategies according to the changes in larger environment surrounding Japanese ceramic collecting in the West, greatly influenced how Van Horne interacted with his dealers at certain stages of his collecting. The shifting notion of “what consists of authentic Japanese ceramics,” as well as changing emphases in the mode of collecting – from taxonomic to art historical – were the key elements in examining the dealers’ role in Van Horne’s collecting activities.

Fig. 3: William Cornelius Van Horne, D.B.: Japanese Pottery: Collection of W.C. Van Horne January 1st 1893, mixed media on paper. 20.2017. MMFA, William Cornelius Van Horne Fonds, Archives of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest

The influence of art dealers on the Van Horne collection stands out when compared to other, similar collections, in particular those of Morse and Freer, due to its transitional position within the shifting approach towards Japanese ceramics. Morse, who started collecting Japanese ceramics in Japan a decade earlier than Van Horne, adhered to his taxonomic and exhaustive approach, which enabled him to establish a large collection of over 6,000 objects.7 Freer, whose interests in Japanese ceramics began slightly after Van Horne, created a more selective collection of about 700 ceramics, based on the artistic quality of individual pieces.8 The Van Horne collection, situated in the middle of the shift, reflected the changing modes of collecting Japanese ceramics in a more stark manner.

Fig. 4: William Cornelius Van Horne, A.B. (second volume of his catalogue of Japanese ceramics, not dated), mixed media on paper. 19.2017. MMFA, William Cornelius Van Horne Fonds, Archives of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest

In the early development of the Van Horne Japanese ceramic collection, Akusawa Susumu (active from the late 1880s to the late 1890s) (fig.5), the first Japanese dealer that Van Horne dealt with, played a significant role.9 Although little is known about how Akusawa operated his business in North America, his transactions with Van Horne reflected the contemporary norms of Japanese ceramics collecting in the 1870s and 1880s. Items he dealt with most often were refined ceramics with colourful painted decoration – porcelain pieces of Imari, Kutani, Nabeshima, or Hirado, as well as Satsuma nishikide (brocade)-type earthenware – all made exclusively for export. Van Horne acquired from Akusawa approximately 160 pieces of export wares between 1887 and 1893.10 The prices for these pieces were often higher than those which Van Horne would pay after December 1892. For example, Van Horne purchased a Satsuma incense burner for 315 dollars (fig. 6), while his later acquisitions ranged from ten to fifty dollars each.11

Fig. 5: Artist unknown, Japanese scroll depicting the Van Horne family with dealer Akusawa Susumu, ca. 1890. Watercolour, pen and ink on layers of silk fabric and paper, 128 x 87 cm. Department of Tourism, Heritage & Culture, New Brunswick. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid

Akusawa was among the initial catalysts for Van Horne’s Japanese ceramics collections. When Van Horne began writing his catalogues in early 1893, he referred to Akusawa as one of the three major sources of information he consulted, along with Edward Morse and Shugio Hiromichi (1853–1927). His trust in Akusawa’s knowledge at the time is apparent. However, Akusawa’s contribution to the subsequent development of the Van Horne collection was limited: his comments appear mainly on export ware and do not feature in the catalogues after September 1893. Van Horne’s interaction with Akusawa significantly decreased after 1893, as his interest in Japanese ceramics shifted to a variety of ceramics made for daily use. Van Horne purchased occasionally from Akusawa until 1896 (and once in 1900), but the dealer seemingly disappeared from Van Horne’s circle of contacts by the early 1900s.

The shift in Van Horne’s interest from export ware to humbler and simpler types made in different kilns throughout Japan for the domestic market was apparently triggered by his encounter with Matsuki Bunkio (1867–1940), a disciple of Edward Morse, who started his dealership business in Salem and Boston in 1892 (fig. 7). As shall be discussed, the high prices set by the leading Paris dealer benefitted the emerging dealers in North America. Matsuki was a prime example of this; his dealership had the most profound impact on the direction of Van Horne’s collection. From 1893 on, Matsuki remained the major dealer for Van Horne throughout his collecting life. A close examination of their client-dealer relationship reveals that the shifts and currents in Van Horne’s collecting activities reflected not only the conditions in his milieu, but also those on Matsuki’s side – his business and marketing strategies as well as his personal life.

It is most likely that Morse, Van Horne’s friend and fellow collector of Japanese ceramics, introduced Matsuki to him. When Van Horne acquired his first thirty-four pieces from Matsuki in December 1892, this purchase was approved by Morse, which indicates the relationships between the three.12 These pieces from twenty different kilns introduced a much larger variety of objects to Van Horne’s Japanese ceramic collection. They included, among others, a Minpei ware tea bowl from the Awaji island and a Karatsu ware sake bottle from the Saga prefecture (fig. 9). The launch of multi-volume catalogues of Van Horne’s Japanese ceramic collection at the beginning of 1893 demonstrates the impact of the encounter with Matsuki and his merchandise. Van Horne’s creation of a separate catalogue around 1896 with fine, colour illustrations, mostly with objects acquired from Matsuki (fig. 8), as well as the production of nearly 100 watercolours of individual Japanese ceramics in 1896, also indicate a significant influence of this dealer on his collection (figs. 10 and 11).

Fig. 6: Satsuma ware incense burner, earthenware, Edo period, 19th century. Royal Ontario Museum 944.12.11. With permission of the Royal Ontario Museum © ROM

Fig. 7: Matsuki Bunkio (1867-1940); Photo courtesy of

International Research Center for Japanese Studies.

The peaks of Van Horne’s purchases from Matsuki first appeared around 1893–1894, when Van Horne acquired 167 objects; and second, around 1897–1899, when 251 objects were purchased. These pieces mainly included small stoneware from kilns throughout Japan; less numerous were export wares with painted decorations. During the early 1890s Matsuki introduced the North American public to selections of Japanese objects that were “different” from the previously accessible types.13 His selection of ceramics was diverse: he offered “a considerable assortment of items from many provinces of Japan, naming at least a dozen different types of ceramics at any given time.”14 By the 1890s, American collectors’ fascination with Japan was already more than a decade old, and it is likely that Matsuki’s customers already possessed a certain knowledge of Japanese arts and crafts.15 It was also the time when the “consumer non-collector” of the middle class emerged, as opposed to the upper-class “collector” of Japanese ceramics.16 As the Japanese ceramic industry targeted the former and produced affordable utilitarian ceramics, the quality of production decreased.17 By making the best use of newly established retail tools – flyers and newspaper advertisements18 – the ambitious young dealer Matsuki contrasted these mass-produced ceramics with his merchandise, thus legitimizing the latter with notions of originality and authenticity. In a newspaper advertisement, he emphasized that the Japanese objects widely available on the American market were “cheaply made, therefore easily broken … [and] miserable” or “not genuine, but imitations … which are made so as to deceive the admirers of the Japanese art,” whereas his own merchandise was “the true work of the best artists in Japan,” and “found in daily use in the Japanese homes themselves.”19

Fig. 8: A page from William Cornelius Van Horne, D.B.: Japanese Pottery: Collection of W.C. Van Horne January 1st 1893, mixed media on paper. 20.2017. MMFA, William Cornelius Van Horne Fonds, Archives of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest

Matsuki’s diverse selection of Japanese ceramics was possible because he traveled to Japan annually. Hina Hirayama suggests that Matsuki was able to develop an extensive network among living potters, as well as traders in Japan, and he even commissioned some ceramic objects specifically made for his merchandise.20 Another factor that enabled Matsuki’s business to flourish were his lower prices compared to other dealers in Salem and Boston. This can be observed from Van Horne’s catalogues; among the items bought from Matsuki in December 1892, the highest price was thirty-five dollars, while Van Horne had occasionally paid as much as 315 dollars for a Satsuma piece offered by Akusawa a few years earlier. Van Horne, who did not mind paying considerable amounts for Western paintings, painstakingly catalogued a number of Japanese ceramics that cost him as little as five to ten dollars each. But it means that the low prices were an important factor that enabled Van Horne to purchase many objects at once and satisfied his eagerness for studying and identifying individual objects.

Fig. 9: A page from William Cornelius Van Horne, untitled catalogue (not dated). Courtesy of Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario.

For Van Horne, Matsuki was important not only as a source of objects, but also of information. Matsuki’s numerous comments and his translation of texts from Japanese sources are recorded in Van Horne’s catalogues and notebooks. Van Horne and Matsuki maintained a close client-dealer relationship for a long time. Matsuki repeatedly visited Van Horne in Montreal,21 and sometimes brought him rare Japanese food by request.22

Fig. 10: William Cornelius Van Horne, Large sake bottle in grey with design of kicking horses, 1896, watercolour. Courtesy of Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario.

The decrease in Van Horne’s acquisitions from Matsuki after 1901 seems to reflect a shift in Matsuki’s merchandise as well as personal reasons on the part of Van Horne.23 By then, Matsuki was attempting to pivot from being a dealer of affordable objects to a “fine art” dealer of more expensive pieces,24 and began to hold auction sales in various locations such as Boston, Philadelphia, and New York. This was reflected in Van Horne’s acquisitions: for example, a vase attributed to the acclaimed Nonomura Ninsei (active mid-seventeenth century) purchased from Matsuki in December 1900, cost him seventy-five dollars.25 Such a high price was atypical in comparison to previous purchases from this dealer. Van Horne stopped acquiring from Matsuki after 1905, when his enthusiasm for acquiring Japanese ceramics began to wane.

Matsuki’s move, in fact, reflected the changing environment of “collecting Japan” that occurred at the turn of the twentieth century. With a greater desire among collectors and scholars for a systematic, art historical understanding of Japanese art in both Japan and the West, ceramic objects were increasingly seen as works of art rather than mere collectables. Dealers, including Matsuki, needed to follow this market shift and appeal to the aesthetic quality of individual ceramics rather than sheer variety and quantity. Yet Matsuki’s attempts to become a fine art dealer failed and by the early twentieth century he faced major financial problems.26 Although Van Horne and Matsuki remained in contact until Van Horne’s last days in 1915, the relationship eventually turned unpleasant for Van Horne; correspondence between them in 1914 indicate conflict in areas of both finances and trust.27 A letter from Van Horne to Matsuki dated 28 December 1914, for example, suggests that Matsuki had asked for financial assistance from Van Horne, but the latter instead complained about the former’s incomplete delivery of the most recent transaction.28

Fig. 11: William Cornelius Van Horne, Shino ware tea bowl with design of silver grass and tea bowl with thick green glaze on mouth, 1896, watercolour. Courtesy of Edward P. Taylor Library and Archives, Art Gallery of Ontario.

As Van Horne’s encounter with Matsuki in 1892 changed the direction of his collecting practice from export ware to ceramics for the Japanese domestic market, a dealer’s tactile presentation of his merchandise could have a great impact on what a collector would acquire. This shift in collecting Japanese ceramics in the West, however, had already been seen in Europe during the 1870s, especially in France, and had been initiated by a leading dealer of Japanese art, Siegfried Bing (1838–1905). It is interesting that Van Horne, whose fame as an emerging American “nouveau-riche” collector was known in Europe, had no major transactions with Bing.

The reason why Van Horne rarely dealt with Bing can also be analyzed from the perspective of the dealer’s marketing strategies. First, the North American market for Japanese ceramics experienced a slight time lag in the availability of objects from Europe in the 1880s. Since the 1870s, Bing had introduced the idea of “authentic Japanese taste” to European collectors. Instead of the colorfully painted ceramics created exclusively for export to the West that had previously been popular, he promulgated simple and sober stoneware and earthenware produced for the Japanese domestic market, often related to the tea ceremony.29 Bing was one of the most conscious tastemakers of his time30 who developed new marketing strategies, including the publication of a highly informative monthly journal Le japon artistique in French, English and German, between 1888 and 1891.

Fig. 12: A page from Sir William Cornelius Van Horne, D.B.: Japanese Pottery: Collection of W.C. Van Horne January 1st 1893, mixed media on paper. 20.2017. MMFA, William Cornelius Van Horne Fonds, Archives of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

Bing’s marketing tactics in North America demonstrate the power of a dealer over the perception of what constituted authentic Japanese ceramics.31 According to Gabriel Weisberg, Bing did not offer objects of the highest quality when he expanded his market to the other side of the Atlantic, because he thought American collectors were lacking “the necessary degree of sophistication to build a towering collection.”32 Bing’s market offer was a significant factor in shaping the idea of authenticity in collecting Japanese ceramics among North American collectors although he was not necessarily willfully deceiving his clients.33 Bing started trading in North America in the late 1880s; the first sale took place in New York in 1894. While French collectors had shifted their interest from export wares to utilitarian pieces and further to those associated with the tea ceremony by the mid-1880s,34 North American collectors, as latecomers to the circle of collecting Japan, were not exposed to the depth of information or variety of objects that their European counterparts were.35 Only a few collectors of Japanese ceramics in North America went beyond export wares before the late 1880s.36 In 1883, when Van Horne first purchased Japanese ceramics in Montreal, the emerging notion of authentic Japanese ceramics set forth by Bing had not entirely taken hold in North America.

Fig. 13: A page from Sir William Cornelius Van Horne, A.B. (not dated), mixed media on paper. 19.2017. MMFA, William Cornelius Van Horne Fonds, Archives of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

While Van Horne’s limited transaction with Bing can be explained in part by this geographical gap in the availability of and information about objects, there was also an additional factor: their pricing. Bing’s objects were reputably more expensive than those of others, even though he may not have offered the best pieces to the American market. Edward Morse, for example, complained about the high price of Bing’s objects.37 Van Horne’s concern about these prices was already evident in his notes in 1888, when he first purchased Chinese ceramics from Bing through a New York dealer and proudly recorded the ten percent discounts he received.38 At Bing’s first sale of Japanese objects in New York in 1894, Van Horne bought three ceramics,39 of which were two Karatsu tea bowls (fig. 12). They cost him forty and twenty-five dollars respectively,40 prices slightly higher than those of objects he acquired from other dealers around the same time. After this purchase, Van Horne did not acquire any more Japanese ceramics from Bing. By the time the latter started selling in North America in 1894, other dealers, such as Matsuki Bunkio, had begun dealing in similar types of Japanese ceramics for lower prices. The influx of more affordable Japanese ceramics was a significant factor in Van Horne’s desire to collect them in large quantities for research, and one dealer’s merchandise had a marked effect on the collector’s perspective.41

Fig. 14: One of the tea bowls Van Horne purchased from Yamanaka in March 1899. Ogata Shuhei (1788-1839), Tea bowl, early nineteenth century, stoneware. 1944.Ee.20. MMFA, Adaline Van Horne Bequest. Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

Matsuki’s later shift toward dealing fine art influenced his relationship with Van Horne; yet, the same transformation had a noticeably different outcome for another dealer, Yamanaka and Company. Along with Matsuki, Yamanaka and Company were a major source of objects for Van Horne between 1898 and 1900. Van Horne mainly dealt with Yamanaka in Boston from 1898 on,42 purchasing a variety of Japanese ceramics in bulk, as he did from Matsuki – 120 pieces in 1898 alone.43 A letter from Yamanaka in Boston to Van Horne, dated January 6, 1899, indicates that the company considered him as an important client.44 It describes a collection of 150 pieces of Japanese ceramics, which Mr. Yamanaka of Boston “specially” selected in Japan with Van Horne’s suggestions in mind – many pieces are “with mark”.45 Therefore, the letter continues, “we feel that you [Van Horne] should have the first opportunity to examine them.”46 The fifty-five pieces Van Horne bought from Yamanaka in March 1899 might have been among those mentioned in this correspondence (figs. 13 and 14). Van Horne established a firm client-dealer relationship within a year. Yamanaka also provided Van Horne with expertise on Japanese ceramics. Comments in the Van Horne Catalogue are annotated with “Yamanaka” or “Y,” and letters reveal that Van Horne used to ask the company for help in identifying potter’s marks on his Japanese ceramic pieces.47

Van Horne’s relationship with Yamanaka did not last long, however. The number of pieces Van Horne purchased from Yamanaka declined dramatically in 1900 and 1901. And in 1902 he made only one purchase from this dealer, which marked the end of their transactions. The concurrent shift in the Japanese ceramic market that has been noted above – toward emphasizing aesthetic aspects of individual objects – may explain Yamanaka’s exit from Van Horne’s collecting circle. The turn of the twentieth century marked a time when dealers of Japanese objects transitioned from considering themselves as traders to art dealers.48 Unlike Matsuki who struggled with the shift, Yamanaka successfully established itself as an art dealer, and its overseas business further flourished after 1900 by dealing also with newly-emerging Chinese works of art.49 The short-lived relationship between Van Horne and the Yamanaka firm exemplifies the ways dynamics between collectors and dealers shifted in response to fluctuating ideas in the Western market about what constituted authentic Japanese ceramics.

Van Horne’s decisions concerning acquisitions for his Japanese ceramic collection were highly contingent on the conditions of the market as well as the personal economies of the art dealers he dealt with, such as Akusawa Susumu, Matsuki Bunkio, and Yamanaka and Company. Their merchandise and marketing strategies were, in turn, subject to the dynamics of the broader cultural and economic environment that surrounded the collecting of Japanese objects at the turn of the twentieth century. In particular, they were affected by shifts in understanding of “what constitutes authentic Japanese ceramics”, from decorative pieces that reflected Western tastes, to utilitarian objects for daily use among the Japanese, to ceramics of “fine art” quality. While Van Horne’s strong preference for certain objects – assorted types from different places throughout Japan – was apparent, his personal taste was not the sole determinant of his collection.

By investigating the Van Horne Japanese collection through the lens of his wide interactions and exchanges with art dealers, rather than merely through his tastes and preferences, it becomes evident that a collection is a complex, collective operation. This emphasis further reveals the extent to which a collection is not merely an untainted reflection of the subject’s self-identity, but is also shaped by historical and contingent forces.

Akiko Takesue is a freelance curator and currently Assistant Curator for the upcoming exhibition “Obsession - Sir William Van Horne’s Japanese Ceramics,” to be held at the Gardiner Museum, Toronto in the autumn of 2018 and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in spring 2019.

1 Pieter Ter Keurs, ed., Colonial Collections Revisited (Leiden: CNWS Publications, 2007), 4.

2 Van Horne became General Manager of CPR in 1882 and President in 1888. He oversaw the completion of the trans-Canada railroad in 1885, and launched steamship services between Canada and Asia in 1891. After resigning the CPR presidency in 1899, he was involved in railway building in Cuba and other enterprises.

3 Out of the 1,200, approximately 200 are now housed at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) in Toronto, and another portion of 200 are at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA).

4 Two of the seven volumes of the Van Horne catalogues are now reserved in the archives of the MMFA, and the five are in the Archive of the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto.

5 Van Horne repeatedly reorganized and renumbered his collection, sometimes as a result of removing some objects through donation, exchange, or gift.

6 Richard Wilson, Tea Taste in the Era of Japonisme: A Debate, in Chanoyu Quarterly 50 (1987), 38.

7 The Morse collection of Japanese ceramics is now housed in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

8 Freer’s Japanese ceramic collection is reserved at the Freer and Sackler Gallery.

9 Akusawa’s background is unknown, except for a few records indicating that he worked for the Japanese commissioners for the Philadelphia Expo in 1876, and as of 1916, he was a wealthy moneylender living in Kōjimachi, Tokyo. (Note: all Japanese names in this article are in the order of surname first and given name second).

10 Invoices dated 1889–1890, and those not dated, Box-folder 13-1, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

11 William C. Van Horne, D.B. (Catalogue of Japanese Pottery: Collection of W.C. Van Horne),1893, not paged. MMFA Archive.

12 Van Horne noted at the bottom of the page of the catalogue: “Note—all pieces purchased from B. Matsuki Dec.’92 approved by Prof. Morse.” Van Horne, D.B., not paged.

13 Hina Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste: Construction of Knowledge about Japan in Boston, 1880-1900 (PhD Dissertation, Boston University, 1999), 222-225.

14 Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste, 226.

15 Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste, 217.

16 Christine Guth, Ibunka hyōka ni okeru kotoba no omomi: 19 seiki ōbei no kyurioshitī, kyurio to Nihon (The Loaded Language of Cross-Cultural Evaluation: Curiosities, Curios, and Japan), tr. Hiroyuki Suzuki, in Bijutsu Kenkyū 388 (Feb. 2006), 331.

17 Hidetoshi Miyaji, Kindai Nihon no Tōjiki-gyō: sangyō hatten to seisan soshiki no fukusōsei (The Ceramic Industry in Modern Japan: Industrial Development and Multi-tiered Production Organizations) (Nagoya: Nagoya Daigaku Shuppankai, 2008), 51.

18 Frederic A. Sharf and Bunkio Matsuki: “Salem’s Most Prominent Japanese Citizen”, in Hina Hirayama and Frederic A. Sharf, “A Pleasing Novelty”: Bunkio Matsuki and The Japan Craze in Victorian Salem (Salem, MA: Peabody & Essex Museum, 1993), 144.

19 Quoted in Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste, 222.

20 Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste, 227.

21 Norma Morgan, ‘F. Cleveland Morgan and the Decorative Arts Collection in The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’ (MA thesis, Concordia University, 1985), 49; Valerie Knowles, From Telegrapher to Titan: The Life of William C. Van Horne (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 296.

22 Correspondences between Van Horne and Matsuki around 1912–1914. Box-Folder 5-2, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archives.

23 Van Horne started working on the Cuban national railway after 1900, which resulted in less time for collecting.

24 Hirayama, A True Japanese Taste, 229.

25 William C. Van Horne, untitled catalogue of Japanese ceramics, n.p. Box-Folder 9-4, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

26 Thomas Lawton, Freer: A Legacy of Art (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1993), 108.

27 Charles L. Freer also had a difficult time with Matsuki around 1909, regarding “their long-standing financial entanglement.” Lawton, Freer, 108.

28 Box-Folder 5-2, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

29 Bing’s inspiration for more ordinary Japanese ceramics was Ninagawa Noritane, Japanese scholar, government official, and dealer of ceramics, who published Kanko Zusetsu (Illustrated Discourse of Ancient Objects) in 1876–79. This multi-volume publication with hand-coloured lithograph illustrations was translated into French and English around 1880 and served as the timely textbook for the Westerners interested in Japanese ceramics.

30 Christine Shimizu, The Appreciation and Study of Japanese Art, in Gabriel. P. Weisberg, et al., eds., The Origins of L’Art Nouveau: The Bing Empire (Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 2006), 48.

31 Gabriel P. Weisberg, S. Bing in America, in G. P. Weisberg and Laurinda S. Dixon, eds., The Documented Image: Visions in Art History (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1987), 56-57.

32 Weisberg, S. Bing in America, 57.

33 Weisberg, S. Bing in America, 57.

34 Imai Yūko, Changes in French Tastes for Japanese Ceramics, in Japan Review 16 (2004), 110-116.

35 Gabriel P. Weisberg, Japonisme: The Commercialization of an Opportunity, in Julia Meech-Pekarik and Gabriel P. Weisberg, eds., Japonisme Comes to America: The Japanese Impact on the Graphic Arts 1876-1925 (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1990), 16-17.

36 For example, William and Henry Walters (1820–1894 and 1848–1948) in Baltimore collected a variety of Japanese ceramics from 1876 on; Henry and Louisine Havemeyer (1847–1907 and 1855–1929) acquired a number of Japanese tea caddies in 1884; in 1885, Thomas E. Waggaman in Washington D.C. purchased the majority of 800 Japanese ceramics from the collection of Frank Brinkely (1841–1912), an English journalist.

37 Chikamasa Ninagawa, Mōsu no tōki shūshū to Ninagawa Noriane (Morse’s Ceramic Collection and Ninagawa Noritane), in Takeshi Moriya, ed., Kyōdō Kenkyū Mōsu to Nihon (Collaborative Study: Morse and Japan) (Tokyo: Shogakkan, 1988), 407.

38 “Inventory” taken by Van Horne on 25 November 1898. Box-Folder 11-2, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archives.

39 Van Horne, D.B., not paged.

40 Van Horne, D.B., not paged.

41 Similarly, Van Horne’s interaction with Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906) was also limited. He met him in 1898, and around 1903 acquired from him eight pieces by Makuzu Kōzan and Takemoto Hayata. Their first transaction seems somewhat late, considering that Van Horne had started seriously collecting Japanese ceramics in 1892, and Hayashi had already been well-known in Paris and offering domestic Japanese ceramics from the mid-1880s. While Hayashi dealt with Henry O. Havemeyer in New York in 1895, Hayashi’s sales in North America were not as extensive as Bing’s.

42 Although the website of Yamanaka and Company states the opening of Boston branch in 1899, Van Horne already dealt with them as early as March 1898 and received letters from the company with its official letterhead. Letters from Yamanaka to Van Horne, Box-Folder 6-2, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

43 William C. Van Horne, A.B. [untitled second catalogue of the Van Horne collection], not paged. MMFA Archive.

44 Box-Folder 6-6, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

45 As mentioned, Van Horne’s main interests in Japanese ceramics lay in identifying the maker and the kiln where individual pieces had been made. Therefore, pieces bearing potters’ marks were especially important for him. For this reason, Van Horne apparently attempted to learn some Chinese characters too.

46 Letter from Yamanaka in Boston to Van Horne, dated 6 January 1899. Box-Folder 6-6, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

47 For example, a letter from Yamanaka to Van Horne dated July 26, 1898 is about the three marks identified, most likely on Van Horne’s request, and the one which “we have been still trying to make out.” Box-Folder 6-2, Van Horne Family Fonds, AGO Archive.

48 For the shifting function of Japanese art dealers along with the establishment of the country’s art system, see Satō Dōshin,’Nihon bijutsu’ no shijō keisei (Market formation for ‘Japanese art’), in Bijutsu-shō no Hyakunen: Tokyo Bijutsu Kurabu Hyakunen-shi (Art Dealers’ Hundred Years: History of the Tokyo Art Club) (Tokyo: Tokyo Bijutsu Kurabu, 2006), 89-108; and Masako Yamamoto, Bijutsu-shō Yamanaka Shōkai: kaigai shinshutsu izen no katsudō o megutte (Art dealer Yamanaka and Company: Its Activities before the Expansion to Abroad), in Core Ethics 4 (2008), 371-382.

49 The company’s success is well exemplified in the fact that its New York branch moved to a five-story building on Fifth Avenue in 1917, and that it received the royal warrant from George V in 1919. See the website of Yamanaka and Company.