This article examines the exhibitions and sales of Yuanmingyuan (“Summer Palace”) loot taken from China in October 1860 by two soldiers in the Anglo-French armies – James Bruce, 8th Earl of Elgin (1811-1863) and Captain Jean-Louis de Negroni (b.1820). Both men displayed their collections before auctioning them – the former in the prestigious South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) in 1862; the latter in a well known exhibitionary site, the Crystal Palace in Sydenham, south London, in 1865. These public exhibitions were clearly being utilised as devices for enhancing the value of collections destined for the art market.

A number of authors have, to date, explored various aspects of the collecting and display of Summer Palace objects in the West.1 In particular, Howald and Saint-Raymond’s recent paper on the art market in France provides a detailed investigation into the sale of Summer Palace objects in Parisian auctions from 1861 to 1869, outlining patterns of sales, purchasers and prices.2 Hill, Green, Ringmar and Lewis have all discussed the significance of Captain Negroni’s collection from the Summer Palace.3 This article will add to the literature by focussing on the newspaper coverage of Negroni’s Crystal Palace exhibition, as well as his 1866 auction at Foster’s, drawing on a rare annotated copy of his sale catalogue.

The 1860s and 1870s were a key period in the sale of Summer Palace objects in both Britain and France. Material flowed from China’s Yuanmingyuan in Beijing, from October 1860, to Europe, and was initially disseminated and dispersed through the mechanism of the auction house.4 Auctions, at this time, were key to the wider market structure, and became fundamental, in particular, to the circulation of Summer Palace loot in England from March 1861, with Christie, Manson & Woods dominating the sales.5 The decades of the mid-late nineteenth century, more generally, have been characterised as the “crucible years” for the development of the art market in London, when the city became the primary centre for global commodity exchange and home to increasingly powerful commercial venues.6 As Fletcher and Helmreich assert:

It was in London that the structures and mechanisms that have come to characterise the commercial art market system, including ... the professional dealer, the exhibition cycle and its accompanying publicity, and a global network for the circulation and exchange of goods, first emerged and developed into their recognisably modern forms.7

This paper focuses on the commercial and exhibitionary practices at play in the dispersal of Elgin’s and Negroni’s collections of Summer Palace loot. It examines how these objects became enmeshed in the interacting system of auction, dealer and exhibitionary sphere, emphasising the role of auction houses, the significance of British press coverage in confirming the quality and value of collections, and the inter-relationships with prominent sites of public display in 1860s and 1870s London.

Exhibiting and Auctioning Elgin’s Collection (1861-1874)

Lord Elgin is the most renowned of the British soldiers associated with the Second Opium War (1856-1860). As High Commissioner and Plenipotentiary to China, he was in charge of the British army which looted the imperial palaces of the Yuanmingyuan from 7- 9 October 1860. Most notoriously, he gave the order, on 18 October, to set fire to and destroy the entire site.

During his time in China, Elgin reportedly commented that, though he “would like a great many things that the palace contains”, he was in fact “not a thief”.8 Despite the proclamation, Elgin nevertheless managed to form a collection of Yuanmingyuan material.9 In January 1862, not long after the campaign, he lent eleven of his Chinese objects to the South Kensington Museum10 – including a crutch in wood mounted in bronze gilt and engraved, as well as eight pieces of jade, a cloisonné enamel vase and an earthenware bottle.11 Apart from the crutch – selected to signify the immobility and fragility of China’s emperor12 - there was here an emphasis on jades and small, functional pieces, rather than large spectacular objects.

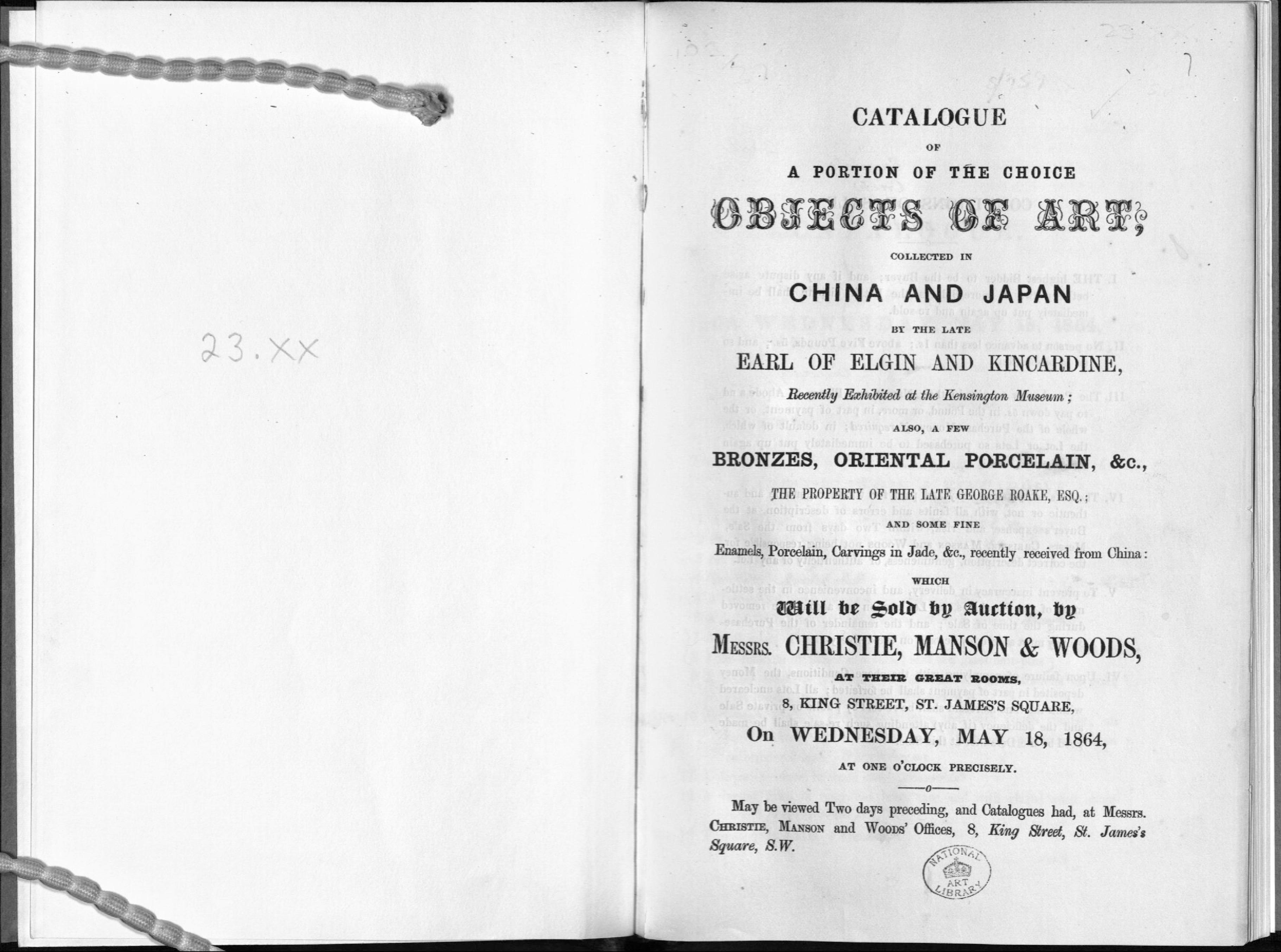

Fig. 1: Front cover of Elgin sale catalogue

“Catalogue of a portion of the choice objects of art, collected in China and Japan by the late Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, recently exhibited at the Kensington Museum”.

Christie, Manson & Woods on 18 May 1864.

Out of copyright. I am grateful to Dr Christine Howald for sending me a pdf of this front cover.

After his death in November 1863, on 18 May 1864 Elgin’s collection was put for sale by Messrs. Christie, Manson & Woods, the most important auction house in London at this time.13 (Fig. 1).

The South Kensington Museum exhibition and the auction house intersected here as two of the key spaces for the display and consumption of Chinese/Summer Palace objects in the capital. This exhibitionary sojourn in the UK’s most eminent design museum enhanced the biographies and pecuniary status of the objects. While Summer Palace provenance does not figure in the auction catalogue, it is evident from the descriptions that some of the pieces were of imperial quality and originated from the Yuanmingyuan.14

Elgin’s collection was listed first in the catalogue, as Lots 1-86, organised into a general section (Lots 1-14), followed by “Lacquer Work” (17-26), “Porcelain” (27-49), “Bronzes” (50-62), “Enamels” (63-68) and “Carvings in wood/jade etc” (69-86 ). For most items, the hammer came down between £1 and £10. Enamels, however, gained much higher prices, averaging £٣١ compared with £٢ for lacquer and porcelain. An interest in jades and ivory was evident: one piece selling for £18.15 By far the most highly priced were two censers:

Lot 67 – an incense-burner, of extraordinary size, on three feet, surmounted by masks of metal-gilt, and with mask and ring handles, enamelled with flowers in colours on turquoise ground, the cover of enamel, pierced, and surmounted by a kylin of metal-gilt – 3ft 6 in high - £60.

Lot 68 – a ditto, on three feet, enamelled with flowers and ornaments in brilliant colours on turquoise ground, the cover of enamel, pierced and surmounted by a metal-gilt kylin – 3 ft 2 in high - £79.

Both pieces were acquired by William Hewitt, a dealer in Oriental material, who had a prominent role in forming the China Courts at both the 1851 Great Exhibition and the 1862 International Exhibition in London.16 Later, Hewitt sold Chinese artefacts to the South Kensington Museum.17 We can see here then the strategic engagement of dealers in the consumption and dissemination of Chinese material, as well as the burgeoning nexus between dealer, auction, exhibition and museum. Other lots were purchased by established London figures in the trade - William Wareham, a “dealer in curiosities” and “works of art”, based in Leicester Square,18 Robert Carter19, Henry Durlacher20, Richard Gale21, Emanuel Marks,22 Charles Rhodes23 and Samuel Willson.24 Westgarth and Fletcher & Helmreich have highlighted the crucial position of dealers in the art market at this period and how, by the mid-nineteenth century, the “system of middlemen” was well established.25 Many of these professional dealers too, it should be noted, had premises clustered around London’s West End.26

The symbiotic relationship the market had with press was evident from the range of newspapers covering the Elgin sale.27 Many noted how once “submitted to public competition”, Elgin’s collection “excited very great interest” and “was numerously attended”: a large majority of the aristocracy had turned out, keen to acquire mementos of the late Governor-General of India.28 Details of buyers and costs are included in the newspaper reports29 and even such a non-metropolitan organ as the Alloa Advertiser chose to offer its readers all the details:

…an incense burner of extraordinary size; two Chinese sceptres formed of twisted canes; a small hexagonal teapot; an opium pipe and case; a curious male figure of metal; cylindrical seal of green stone, surmounted by a group of kylins; a figure of a fakir; three cups of soapstone and a large of number of jade slabs, basins, and bowls.30

The Leeds Times provided the most extended and, indeed, surprisingly critical account. It compared the looting of the Yuanmingyuan with the imagined destruction, by a foreign army, of the British Museum, National Gallery, South Kensington Museum, and Windsor Castle, or the burning and sacking of the Louvre and the Tuileries:

Nationally, we pretended to be proud of it at the time, but in a very short space people grew rather ashamed of the transaction, and such officers as brought home with them portions of the plunder were glad enough to convert their booty into cash through the medium of the sale-rooms, pocket the money, and say no more about it. So great, indeed, was the scandal caused by the sale in Paris of some of the plunder brought home by the French that few people, having anything like a sense of delicacy, would like to have it known that they possessed anything in their drawing rooms which had once formed part of the furniture of the great palace. Within the last week, however, London has witnessed a sale which has revived this awkward business upon the public memory.31

A discussion of the “shame” and “scandal” associated with looting was clearly unusual in British imperial culture of the 1860s. Above all, the newspaper condemned the auctioning of a human skull, which “should never have been suffered to have been offered for sale in public in any country claiming to be considered civilised”.32 The Leeds Times thus covers the auction of Elgin’s collection with a degree of criticism rarely observed in the media at this time.

The Elgin family’s involvement with the South Kensington Museum was sustained after James Bruce’s death in 1863. Elgin’s younger brother, Thomas Charles Bruce (1825-1890), for example, provided six pieces of cloisonné “from the Summer Palace” to a special loan exhibition in 1874 of enamels on metal.33 The exhibition was arranged with the most recent objects first, moving backwards to those of earlier times, and organised according to country: European enamels, many from Limoges, were followed by early French and antique Roman pieces. 34 “Oriental” enamels were last, with eleven Chinese objects listed from the Summer Palace: eight lent by T. C. Bruce - two altars on shaped legs, four vases, an incense burner and a dish.

The interlocking relationship of press and museum was evident here too. The London Daily News described Chinese and Japanese work as “wonderfully fine, both in work and in design, as regards both form and colour”.35 The Pall Mall Gazette noted “the pale blue Chinese work”, and other pieces “full of brilliancy…the general effect of the exhibition…has been simply dazzling”.36 The Saturday Review: Politics, Literature, Science and Art believed the exhibition to illustrate the art of enamelling on metal more fully than had ever been seen before.37 Once more Chinese and Japanese material came last, with the passage on China concluding: “The skill…with which the processes are carried out has perhaps never been surpassed”.38 Museums in Britain in the 1860s and 1870s were only just beginning to taken an interest in Chinese cloisonné, an art form never seen en masse in the West, of such consistently high quality, before the looting of the Yuanmingyuan.39 Pearce argues that it was only after 1860 that a particular European taste in high quality Chinese art emerged: the quantity and variety of imperial wares brought back by the soldiers clearly stimulated a fashion for elaborate eighteenth century jades, porcelains, and perhaps, above all, cloisonné enamels.40

Exhibiting and Auctioning Negroni’s Collection (1865-6)

Probably the largest collection of Yuanmingyuan plunder formed by a single soldier was that of Jean-Louis de Negroni. Hailing from Corsica, Negroni enlisted first with the French army as a lieutenant in the 79th Regiment of Line and, in 1859, joined the 102nd Regiment.41 He embarked on 5 December 1859 from Toulon in the Driade, arriving in China in early 1860.42 Before his departure, Negroni described China as a “strange land”, “whose mysterious wonders” had filled him “with intense longing”.43 Fortunately for him, his regiment was among the first to enter the Yuanmingyuan, and it was here that Negroni wrote of catching “sight of some [Chinese] ladies” in one of the “sumptuous apartments”.44 Not only did Negroni apparently open the door to enable the women to escape, but even escorted them to the park gates. As a result, one “empress”, in gratitude, presented him with a beautiful casket containing gems. Negroni explains how he went on to purchase loot from both English and French soldiers in the army camps around the Yuanmingyuan, investing not only his own money but substantial amounts borrowed from fellow soldiers.45 As recounted in his 1865 catalogue:

Works of art it appears, had always a great charm for Captain de Negroni, and, happily, having funds and credit at his disposal, he determined to employ them to the utmost, and endeavour rescue from impending ruin such specimens of the treasures and marvels of vertu with which the Emperor’s Summer Palace at Pekin is connected were most worthy of preservation. He applied himself earnestly to the work, and, undeterred by the risks and difficulties of the enterprise, daily added to his collection till it became one of unparalleled beauty and magnitude. The packing and transportation such articles would alone have deterred an ordinary man, but in spite of all discouragements, Captain de Negroni persevered in his determination of bringing them to Europe, and, dint of courage, energy, and discretion, succeeded beyond his hopes and expectations.46

The collecting motivation of this Corsican adventurer was thus presented in a benign light, with the military looting of objects from China’s imperial palace reconfigured as “saving” them from ruin.47 It was thanks to the “exertions of a few connoisseurs”, the text concluded, that “any fragments” of the Summer Palace were “preserved”.48

Upon his return to France, and in recognition of his twenty three years service, Negroni was granted the title of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, and soon after retired from the army.49 By 1864, he had published Souvenirs de la Campagne de Chine, which not only recounted his adventures in China but comprised a detailed inventory of his objects.50

The Corsican soldier had accumulated the most extensive collection of Yuanmingyuan loot of any individual. This consisted mainly of small, portable, high value European and Chinese artefacts – gold, enamels, jewels, precious stones. There were European clocks, watches, automaton singing birds, musical boxes, portrait caskets of Louis XIV and a box sent to China by Marie Antoinette, some of which would have been tribute gifts from French monarchs to Chinese emperors. Frequent references are made in Negroni’s catalogue to objects belonging to the imperial Chinese family – the Emperor’s official seal, waist buckle and mirror, or the Empress’s hand-glass, jade necklace and scent bottle – a deliberate attempt to assert authenticity and, importantly, add financial value to the objects. Indeed, James Hevia has remarked on the importance, at this time, of associating looted objects from the Yuanmingyuan with the person or body of the Chinese emperor.51

Negroni’s marketing strategy required him to display his collection prominently across key exhibitionary sites in Europe as a prelude to sale in the auction house. He initially exhibited his collection in the Rue Rivoli in Paris, causing a sensation,52 followed by Baden-Baden and other fashionable resorts in Germany, and then finally in England.53 Most notably, his collection was on display at the Crystal Palace for over four months in 1865.54 As the sequel to the Great Exhibition of 1851, the supposedly “permanent” Crystal Palace complex, relocated to Sydenham in south London in 1854, was even larger than its temporary predecessor. And like the Great Exhibition before it, this site functioned as a visible articulation of British imperialist might.55 Negroni’s collection, comprising an astonishing 484 objects, was displayed in the Iron Room, in its own enclosure, in front of the French Court and under the auspices of a Mr. Holt.56 The tasteful arrangement was noted by the Yorkshire Gazette57: albums and paintings were placed around walls and in cases, with lacquered cabinets and caddies displayed of “exquisite workmanship and finish”.58

Negroni’s accompanying catalogue told of his background and his voyage to the East, sprinkled with stereotypical mid-nineteenth century perceptions of the Chinese as “treacherous” and “barbaric”.59 He described in some detail his encounter with the women of the court and the artefacts and interiors observed in the Yuanmingyuan.60 Written in the third person, the text ponders the impact of the destruction of the palace complex: “Historians may pronounce it an act of just retribution on a cruel and perfidious people, or they may find in it a parallel to that remorseless order which gave to the flames the vast treasures of the Library of Alexandria.”61

Once again, newspapers played a key role in publicising Negroni’s collection, which he utilised deliberately to enhance the desirability of his objects. Indeed Negroni exploited the press to maximum effect, garnering huge amounts of attention: over 40 British newspapers reported on his Crystal Palace display. Many proposed a justification for the looting, as well as lingering over the fine qualities and high value of the objects. For the newspaper, The Atlas:

...as their wonder of worth becomes more generally known, their attraction increases. To all true lovers of art or articles of vertu this collection affords unusual means of gratifying their generosity and their taste, while the general public cannot fail to be interested in objects that are so intrinsically valuable and rare.62

The Illustrated London News reported thus: “An interesting collection of Chinese objects of rare beauty and great value…stated to be worth over £300,000”.63 The Times opened in a similar vein: “…one of the most curious, and probably one of the most valuable, collections of the kind that has ever been seen in this country”. Negroni’s jade carvings were particularly noted. There were quantities of precious jewels, “…wonderful works in cameos, carved groups, and vases” of “rare beauty and…value”. The extraordinary size of the jewels were particularly remarked upon, the highlight being Negroni’s “monster sapphire” of 742 carats, claimed to be the “largest in the world”. The collection included luxurious furs and textiles, satins and embroideries, with porcelain said to be “the finest of its kind” ever brought to England. Negroni’s collection, The Times concluded, would surely “prove one of the most lasting attractions of this season”.64

Fig. 2: “Articles in the Chinese Exhibition at the Crystal Palace”

Illustrated London News, 6 May 1865, p 425.

© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans Picture

Library.

The Illustrated London News returned to the exhibition it its 6 May issue, this time with an extraordinary half page illustration of Negroni’s objects, thus amplifying the visibility of his collection in the media. (Fig. 2) The article described a selection of his artefacts: two European timepieces, placed in the centre at the front of the image, were “very pretty and ingenious”. Next to these, on the left and at the front, was a large sardonyx, carved into the shape of a grotto, a “very curious specimen of Chinese art”. The different colours of the stone were “skillfully managed”, so that the grotto was red, one monkey was white, and the other was yellow. Behind this was a “fantastic” and “magnificent” red lacquer cabinet, with its “peculiar ornamentation”, Ming insignia, decoration and jade inlays “of the richest and finest workmanship”. The ivory carving of a ship, in the centre of the image, was considered “beautiful” and the cylindrical vase on the right hand side was “of exquisite design and workmanship”. The smaller jade vessel on the right hand side, despite having handles “of a grotesque shape”, was “of a fabulous antiquity”.

As with Elgin’s collection, newspapers promoted a range of moral perspectives on the looting of the Yuanmingyuan, some more enlightened than others. The Era, for example, referred to the spoils as “lawful”,65 and the Eclectic magazine’s anonymous, 700-word article, “The Chinese Collection at the Crystal Palace”, justified the looting of the palaces, though the text was tinged with regret: “…it was also felt that a royal museum had been destroyed in the confiscation of this favorite residence, leaving a void that could never be similarly refilled.”66 The Yuanmingyuan itself was characterised as “a veritable palace of Aladdin”, with the “Art-history of China for a thousand years…enshrined in these walls”. The pecuniary aspect was once more highlighted with the Empress’s jewel-stand – a principal feature of Negroni’s collection – ascribed a value of 72,000 francs: said to greatly surpass the example in the Mineralogical Museum in Paris. The art of carving jade was admired, as was the quality of the European objects in the collection, and the Eclectic magazine returned to the monetary value. The largest sapphire in the world, weighing 742 carats, was said to be worth £160,000. The text praised the imperial Chinese textiles – a mantle, composed of the throats of around 400 foxes was valued at an extraordinary £٢,٠٠٠. Indeed, when Negroni’s collection left the Crystal Palace in July 1865, it was declared by the Illustrated London News to be worth upwards of £500,000 – an exceptionally high amount (around £٢٩ million in today’s money).67 Negroni’s objects had increased in value by over £200,000 in a mere four months – in preparation, no doubt, for their subsequent relocation to the auction house and the anticipation of high commercial gain.

Before the auction, Negroni’s collection was exhibited one more time, from July-August 1865, at 213 Piccadilly (near the Circus), the premises of Ellam Benjamin, a “Saddler and Whipmaker”.68 Negroni advertised this exhibition extensively, for it was taken up by over 20 newspapers.69 For The Atlas, it was “one of the most remarkable exhibitions ever seen by the public”, a collection of “treasures so unique, beautiful, and costly, that the astonishment excited is not less than the admiration”.70 The London Daily News announced it to be “tastefully arranged”, “perfectly catalogued”.71 The Glasgow Herald’s piece, “Gems and their Value”, highlighted Negroni’s “glorious sapphire”.72 Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper characterised his carvings in jade as “instinct with grace”.73

Negroni’s collection was finally put up for sale in June 1866 by Messrs. Foster, based at the Gallery, 54 Pall Mall - one of the main auction houses in mid-nineteenth century London.74 On the first day of the sale came “Porcelain” (lots 1-49), “Enamels on Copper” (50-54); “European Objects of the Goldsmiths’ Art” (56-96); “Lackers [sic.], Inlaid work, carvings in wood and ivory” (96-115) and “Paintings and manuscripts” (116- 141). On the second day, the auction began at one o’clock with the most illustrious section – “Uncut jewels” (lots 151-244).75 Capital letters were granted to lot 245: “The Empress’ jade necklace”. The following section, “Oriental Jade” (lots 250- 298), also included entries in capitals, highlighting their significance. Here was listed “The Empress’s jewel stand” (lot 250); the “celebrated imperial, junk” (251); the “Empress’s bonbonniere” (259); the “Emperor’s mirror” (262); and the “Empress’s hand glass” (298). Day three began with the collection of “Imperial mantles, silks, furs &” (301-361); followed by “Oriental agates” (362-404) - notable lots being the “Emperor”s Official Seal for Death Warrants” (367) and the “Empress’s scent bottle” (385). “Chinese Jewels” (405-449) included the “Splendid Oriental Sapphire, 48 carats, Chinese mounting in fine gold” (425).

The prices achieved, however, were rather insignificant. Indeed, most pieces sold for between £1 and £10, and key objects profiled prominently in previous exhibitions were not included or were withdrawn. For example, the jewel box supposedly presented to Negroni by the “Empress”, the “Empress’s jewel stand” and the “largest sapphire in the world”. The costly mantle “made from the throats of 400 foxes” (lot 335), was acquired for a mere £27, rather than Negroni’s extravagant estimate of £2,000. The highest figure was paid for lot 365 – a grotto in “Sardonyx” purchased for £210 by a Mr Dollman. The next highest was £١١٠ for lot 364, bought by a Mr Nixon and described thus:

A GROTTO in SARDONYX, with two monkeys. Great taste is displayed in managing the different strata of this superb stone. The grotto is left entirely red, one monkey is white, the other yellow.76

This was the object depicted in the Illustrated London News the previous year – a strategy which now proved its worth in inflating value.

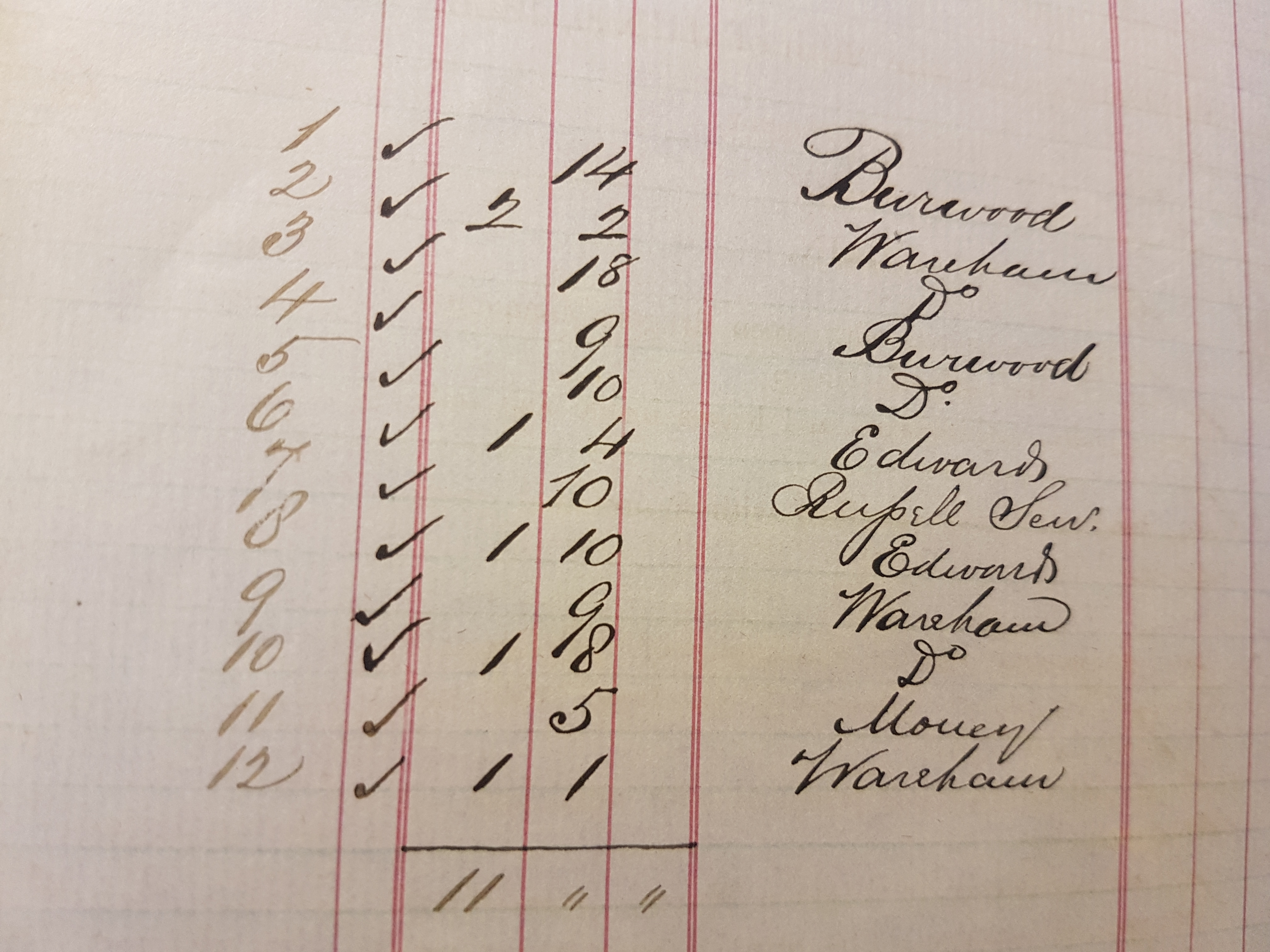

Many of the well-known London “curio” dealers and jewellers attended the auction as their names appear frequently against lots over the three-day period. (Fig 3). In particular, Emanuel77, William Grindlay78, John Coleman Isaac79, Russell,80 Thomas Woodgate81 and William Wright82 consistently bid and won. We see, once again, a set of prominent professional dealers actively engaging with these high quality imperial objects. Wareham, who, as we have seen, bought objects at Elgin’s auction, acquired 23 lots, mainly porcelain, enamels, lacquer and silks, and spent £٦٥ overall.

Fig. 3: Page from Negroni sale catalogue

“Catalogue to the renowned collection of Chinese Art Treasures including Jewels, Jades, Chalcedonies, porcelain silks, furs, curiosities and European goldsmiths work being part of the spoil from Yuen-Min-Yuen, the Summer Palace of the Emperors of China, Pekin”.

Messrs. Foster. 20-22 June 1866.

Out of copyright

The Foster sale clearly did not realise the returns Negroni had anticipated. The hand-written annotations in the catalogue indicate a grand total of just over £١,٤٧٩ as hammer price – a far cry from the “half a million” anticipated in the previous year. Two years later, in France, Negroni’s creditors took him to court for inflating the value of the artefacts. The “melancholy spectacle” of this army officer in the dock was recounted by the London Daily News.83 Convinced that his collection was worth a fortune, he had “formed an exaggerated notion of the value of the nick-nacks”.84 His highly priced diamond was said by two valuers to be “not worth twopence”. The tribunal held that Negroni “had fraudulently raised money by misrepresenting the value of the articles given in pledge”: he was convicted of fraud and swindling, with a one month prison sentence and a fine of 3,000 francs.85 As he attempted to negotiate the art market for his Chinese collection, then, Negroni’s fortunes ended in catastrophe.

This article has examined the circulation and commodification of Summer Palace objects in both Elgin’s and Negroni’s collections in 1860s and 1870s London. We have seen, in particular, the interdependence between the exhibitionary systems of the South Kensington Museum, the Crystal Palace, and Christie’s and Foster’s auction houses, as well as the role of dealers and the Victorian news media in promoting the value of this looted imperial material. While the auction house and exhibition were two key areas of visibility for such collections, there was also a wider system of circulation and pattern of consumption as objects moved from public display, to auctioneer, through the hands of the art dealers, and ultimately on to supposedly permanent resting places in museums. We can also see the significance of the cultural terrain of London as a site of imperial trade. Many of the dealers were based in the heart of the art market in the West End: location, in other words, was key to the success of the marketing and selling of Summer Palace material at this time. Looted Summer Palace objects thus became incorporated into these new contexts – commodified and attributed new values – which only served to embed them more deeply into the structures and cultural meanings of the West.

Acknowledgements

This is part of a larger project to map the Summer Palace diaspora. I am grateful to Steven Lei for all his help with research into the provenance of Summer Palace objects. The comments of an anonymous reviewer were also extremely useful.

Louise Tythacott is the Pratapaditya Pal Senior Lecturer in Curating and Museology of Asian Art at SOAS, University of London.

An earlier version of this article gave less comprehensive credit to research by O.M. Lewis as referenced in footnote 3.

1 See for example, James Hevia, English Lessons: the Pedagogy of Imperialism in Nineteenth-Century China (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2003); Katrina Hill, Collecting on Campaign: British Soldiers in China during the Opium Wars, in Journal of the History of Collections (2012), 1-16; Greg Thomas, The Looting of Yuanming and the Translation of Chinese Art in Europe, in Nineteenth-Century art worldwide: a journal of nineteenth-century visual culture vol. 7, no. 2, autumn (2008): http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/index.php/autumn08/93-the-looting-of-yuanming-and-the-translation-of-chinese-art-in-europe; Kristina Kleutghen, Heads of State: Looting, Nationalism and Repatriation of the Zodiac Bronzes, in Susan Delson, ed., Ai Weiwei: Circle of Animals (New York: Prestel, 2011), 162-183; and most recently the chapters in Louise Tythacott, ed., Collecting and Displaying China’s ‘Summer Palace’ in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France (Abingdon, Oxon; New York: Routledge, 2018) – for example, James Hevia, The Afterlives of a Ruin: The Yuanmingyuan in China and the West, 25-37; Nick Pearce, From The Summer Palace 1860: Provenance and Politics, 38-50; Katrina Hill, The Yuanmingyuan and Design Reform in Britain, 53-71; Stacey Pierson, “True Beauty of Form and Chaste Embellishment”: Summer Palace Loot and Chinese Porcelain Collecting in Nineteenth-Century Britain, 72-86; James Scott, “Chinese Gordon” and the Royal Engineers Museum, 87-98; Kevin McLoughlin, “Rose-water Upon His Delicate Hands”: Imperial and Imperialist Readings of the Hope Grant Ewer, 99-119; and Greg Thomas, Yuanmingyuan on Display: Ornamental Aesthetics at the Musée Chinois, 149-167.

2 Christine Howald and Léa Saint-Raymond, Tracing Dispersal: Auction Sales from the Yuanmingyuan Loot in Paris in the 1860s, in Journal for Art Market Studies, 2/2 (2018), 1-23.

3 Katrina Hill, Collecting on Campaign, 1-16; Judith Green, Britain’s Chinese Collections, 1842-1943: Private Collecting and the Invention of Chinese Art (PhD thesis, University of Sussex, 2002), 84; Erik Ringmar, Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China (New York: Palgrave, 2013), 82-83. In particular, O. M. Lewis, China’s Summer Palace: Finding the Missing Imperial Treasures (High Tile books, 2017), 167-196 and elsewhere, discusses in far greater depth details of the collecting and dispersal of Summer palace loot.

4 James Hevia lists 18 March 1861 as the earliest auction (at Phillips), English Lessons, 94.

5 See Mark Westgarth, ‘Florid-looking speculators in Art and Virtu’: the London picture trade c.1850, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, eds. The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850-1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 29. I have documented 22 auctions between April 1861 and February 1897 at Christie, Manson and Woods, and Phillips of 1, 329 objects from the Summer Palace (see also Hevia, English Lessons, 92-95, and Thomas, Looting, 16).

6 Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, Introduction: The state of the field, in Fletcher and Helmreich, The rise of the modern art market in London,, 2 and 5.

7 Fletcher and Helmreich, Introduction: The state of the field, 1.

8 Robert Swinhoe, Narrative of the North China Campaign (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1861), 300.

9 See also O. M. Lewis, China’s Summer Palace, 211-213.

10 V&A Loan register, 18 January 1862, 70-71.

11 This included a slab of green jade; a slab of light green jade engraved with Chinese characters; a stand in the same material of darker colour; a square vase in white jade; ornament in relief; a small bowl and cover in white jade; a pair of bowls and covers in white jade; a white jade teapot and cover; a white jade bowl; a small cover on sauce boat in white jade; cloisonné vase and an earthenware bottle.

12 See Katrina Hill, The Yuanmingyuan and Design Reform in Britain, in Louise Tythacott, ed., Collecting and Displaying China’s ‘Summer Palace’ in the West: The Yuanmingyuan in Britain and France (New York and London: Routledge, 2018), 54.

13 Fletcher and Helmreich, Introduction: The state of the field, 9.

14 Some of the descriptions in both the V&A list and the auction catalogue are the same. See also Katrina Hill, Collecting on Campaign, 19.

15 Lot 78 - a “beautiful slab of pale-green jade”.

16 Louise Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects: Buddhism, Imperialism and Display (New York and Oxford: Berghahn, 2011), 89.

17 Such as a Chinese screen, chopstick case and fan case in 1866 and a Chinese fan in 1868.

18 Wareham bought eight lots at this sale, though did not buy any jades. See also Mark Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary of Nineteenth Century Antique and Curiosity Dealers (Glasgow: The Regional Furniture Society, 2009), 180.

19 An “antique china dealer” (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 77).

20 Henry, Henry Jnr and George Durlacher were well established art dealers in London in the mid-late nineteenth century (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 90-91). Durlacher acquired only one object at the sale: a tripod incense-burner (lot 58) for £12.

21 A picture dealer based in High Holborn (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 106).

22 Emanuel Marks and his son Murray were major London art dealers in the mid-late nineteenth century, and Murray was later in partnership with the Durlacher Brothers (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 135).

23 This may be Charles Rhodes, listed as a ‘curiosity dealer’ in Oxford Street (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 156).

24 A “curiosity dealer” in Leicester Square and later the Strand (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 187-8).

25 Westgarth, Florid-looking speculators in Art and Virtu, 44, and Fletcher and Helmreich, Introduction: The state of the field, 15.

26 Fletcher, Shopping for Art: the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery, 1850s-90s, in Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, eds., The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850-1939 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2011), 48.

27 Pamela Fletcher, Shopping for art: the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery, 61. I have identified 17 newspapers which cover the auction.

28 Alloa Advertiser, Bells Weekly Messenger, Cork Advertiser.

29 For example, the Cork Advertiser.

30 21 May 1864.

31 21 May 1864.

32 Ibid.

33 P. Cunliffe Owen, Catalogue of the special loan exhibition of enamels on metal held at the South Kensington Museum (London: South Kensington Museum, 1874), xix.

34 Ibid.

35 Special Exhibition of Enamel Work, 8 June 1874.

36 7 October 1874.

37 Enamels on metalwork at the South Kensington Museum, in Saturday Review: Politics, Literature, Science and Art, Vol. 38, No 976 (11 July 1874), 49.

38 Ibid., 51.

39 Susan Weber, The Reception of Chinese Cloisonné Enamel in Europe and America, in Beatrice Quette, ed., Cloisonné: Chinese enamels from the Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties (New York: Bard Graduate Center, 2011), 187-221.

40 Nick Pearce,, Soldiers, Doctors, Engineers: Chinese Art and British Collecting, 1860-1935, in Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History 6 (2001), 45.

41 Catalogue of Captain de Negroni’s collection of porcelain, jade, jewels, silks, stones, furs etc from Yuen-Min-Yuen (The Summer Palace) Pekin (London: McCorquodale & Co, 1865), 3. I am extremely grateful to Katrina Hill for sharing her copy of the catalogue introduction with me. There seems to be only one extant copy, at the New York Public Library. According to Lewis, he was born in a remote village in Corsica (China’s Summer Palace, 178).

42 Catalogue to the renowned collection of Chinese Art Treasures including Jewels, Jades, Chalcedonies, porcelain silks, furs, curiosities and European goldsmiths work being part of the spoil from Yuen-Min-Yuen, the Summer Palace of the Emperors of China, Pekin, 20-22 June 1866, sold by Messrs. Foster. The only annotated copies of this in the UK are held at the National Art Library (V&A) and the Barber Institute, Birmingham.

43 Catalogue of Captain de Negroni’s collection, 4.

44 Ibid., 8.

45 The Times, 30 March 1865 and London Daily News, 11 July 1868.

46 Catalogue of Captain de Negroni’s collection, 10. Unfortunately, I have not been able to discover more details about how Negroni acquired so much material.

47 This mode of collecting was later referred to as “salvage ethnography”. See Chris Gosden and Chantal Knowles, Collecting Colonialism: Material Culture and Colonial Change (Oxford, New York: Berg, 2001), 51.

48 Catalogue of Captain de Negroni’s collection, 10.

49 Ibid., 11.

50 Jean-Louis de Negroni, Souvenirs de la Campagne de Chine (Paris: Renou et Maudle, 1864).

51 Hevia, English Lessons, 86.

52 North London News, 25 March 1865.

53 Ringmar, 82, and London Daily News, 11 July 1868.

54 18 March - 22 July.

55 Tythacott, The Lives of Chinese Objects, 83.

56 Illustrated London News, 25 March 1865; The Times, 30 March 1865; Preston Herald, 25 March 1865 and The Atlas, 20 May 1865.

57 25 March 1865.

58 Cork Reporter, 24 March 1865.

59 Catalogue of Captain de Negroni’s collection, 7. See also Louise Tythacott, British travels in China during the Opium Wars (1839-1860): Shifting Images and Perceptions, in Katrina Hill, ed., Britain and the Narration of Travel in the Nineteenth Century: Texts, Images, Objects (Farnham: Ashgate, 2016), 191-208, for a discussion of similar language used by British soldiers to characterise Chinese people during the Opium Wars.

60 Ibid., 8-9.

61 Ibid.,10.

62 20 May 1865.

63 18 March 1865.

64 The Times, 30 March 1865.

65 26 March 1865.

66 August 1865.

67 22 July 1865. See https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency-converter/.

68 Lewis, China’s Summer Palace, 172.

69 I have identified 22 newspapers.

70 29 July 1865.

71 London Daily News, 19 July 1865, and The Atlas, 29 July 1865.

72 16 August 1865. See also The Hampshire Telegraph, 19 August 1865; Northern Standard, 19 August 1865; Paisley Herald, 19 August 1865 and Dublin Weekly, 19 August 1865.

73 20 August 1865.

74 20-22 June. Catalogue to the renowned collection of Chinese Art Treasures. There were also sales of Negroni’s collection in Paris, though these are outside the remit of this paper. See Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, Introduction: The state of the field, 9 and Lewis, China’s Summer Palace, 182-3, in relation to the auction house.

75 Lot 151, for example, consisted of 108 rubies.

76 Catalogue to the renowned collection of Chinese Art Treasures, 27.

77 This is likely to be Emanuel, Emanuel - a “diamond and pearl merchant” and “jewellers” (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 93).

78 A “curiosity dealer’”and “art dealer” in Pall Mall (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 109).

79 A “curiosity dealer” in Wardour Street whose clients included Augustus Wollaston Franks, Curator at the British Museum (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 121-22).

80 This is likely to be either John or Israel Russell (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 159-160).

81 An “antique furniture dealer” based in High Holborn (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 189).

82 An “antique furniture dealer and cabinet maker” (Westgarth, A Biographical Dictionary, 190).

83 11 July 1868.

84 Ibid.

85 Ibid.