ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Anita Archer

On 31 October 2004, Sotheby’s conducted an auction in Hong Kong under a new category entitled ‘Contemporary Chinese Art’. This was not the first time that either of the multinational auction houses had included contemporary Chinese art in their auction offerings; however, in the decade leading up to this auction, contemporary Chinese art was primarily included in the broader sale category titled Modern and Contemporary Chinese Paintings. By late 2004, Henry Howard-Sneyd, Sotheby’s Managing Director, China, Southeast Asia and Australasia, was cognisant of a significant shift in international market interest in Chinese art of a style comparable to contemporary international art. In fact, Christie’s had offered a substantial number of artworks in this style at an auction in London in October 1998 titled Asian Avant Garde. However, Christie’s auction, which included Japanese, Korean and Chinese contemporary art, was poorly attended and a financial failure. Consequently, Christie’s abandoned this auction category. So what had occurred over the intervening six years that gave Sotheby’s encouragement to inaugurate this auction category?

This article is structured around a unique methodology whereby examination of the contents of the auction catalogue including artists, artworks, provenance, date of production and medium provides a framework for analysis of this emergent auction category. The contextual analysis of Sotheby’s inaugural auction in October 2004 illuminates the networked activities of a small group of dealers, critics and curators acting as cultural mediators to create a global market for the artwork of a select group of Chinese artists. The activities of this network are underpinned through the symbolic value imbued by international museum exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art presented as provenance and exhibition history. According to the 2007 TEFAF report, global art auction sales for contemporary Chinese art grew nearly two hundredfold between 2003 and 2007. This article thereby aims to contribute to an understanding of how the global auction market for contemporary Chinese art was inaugurated and developed.

The current global contemporary art world is intricately interwoven with the economics of art. In particular, an acknowledged global trend is the speculative and investment motivations of collectors whose activities have broader impact on the art world.1 TEFAF’s 2009 Art Market Report documented that between late 2003 and 2007 the market for contemporary Chinese art “grew in volume by 200% whilst average prices increased by over 325%”.2 This exponential growth raises the questions: how, why and where did this happen? Emerging markets provide art market researchers with fertile ground for investigation into how art markets are formed and developed, and it is in this context that this paper examines a single auction event - Sotheby’s inaugural auction of contemporary Chinese art in October 2004. By using an alternative methodology of examination of the auction catalogue as the point of entry for analysis, this paper intends to contribute to a broader scholarly understanding of the mechanics of art market value creation as well as contextualising the emergence of an art auction market category.

Examination of Sotheby’s auction reveals the co-operative activity of a network of cultural mediators providing a foundation for market development.3 The importance of auction houses in the early development of the market for contemporary Chinese art was heightened due to a paucity of infrastructure within Mainland China to provide the “support structure”4 for art world development. The impact of this “innermost circle”5 to achieve its objective was exacerbated by the fact that the supported artists were a relatively small group compared to the extensive number of Chinese artists working within official systems in approved styles. Contemporary Chinese art in the context of the auction market across the first two decades of the twenty-first century specifically relates to a genre of art that, during the 1980s and 1990s, was referred to as “Avant-garde”, “experimental” or “unofficial” art.6 For the purpose of this paper, I use the terms contemporary Chinese art or Chinese art in an international contemporary style in order to reflect the purpose and approach of the art market to this style of art, and to make a clear point of difference to the majority of Chinese art painted by contemporary artists in “traditional” and “official” styles.

Whilst the content of art auctions are highly dependent on the stock available and offered to auction houses for sale by vendors, the contents of most art auctions conducted by the multinational auction houses are still a highly curated affair. Auction houses do not include everything that they are offered for sale. Moreover, the financial data that frames most discussions on the art market derives from the relatively transparent pricing that emanates from auctions; in direct opposition to the opacity of pricing within the primary market of commercial galleries. Yet very little research has been conducted to date into the formation of contemporary art auctions and the strategies auction houses apply to the construction of their sales to add both symbolic and economic value to their offering. Indeed, this research considers the contribution that auction houses may also offer in price formation over and above what Velthuis has referred to as their “parasitic” role.7

Sotheby’s inaugural auction of Contemporary Chinese Art took place in Hong Kong in October 2004 as part of the company’s regular bi-annual Asia Week auction offering which included sales of Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, Fine Chinese Paintings and Magnificent Jewels and Jadeite. This was not the first time that Sotheby’s had conducted a sale of contemporary art from China in Hong Kong; they had been offering artworks in this sale category since the early 1990s. However, the nuanced change of auction sale title from Fine Modern and Contemporary Chinese Paintings to Contemporary Chinese Art revealed a marked shift in content away from traditional, academic style oil paintings to art works in an international contemporary style in a broader range of media. Sotheby’s had tentatively included art of this genre in previous auctions with measured but not overwhelming results.8 By the end of 2004, according to Henry Howard-Sneyd, Sotheby’s Managing Director, China, Southeast Asia and Australasia, the auction house was encouraged by a conflation of commercial and institutional activity resulting in an increasingly receptive collector market, particularly in the form of wealthy expatriate City workers looking to satisfy both interior decoration needs and cultural satisfaction from the acquisition of art from the region.9

Christie’s were also aware of this market growth. They had ventured into this field, unsuccessfully, in London in 1998 with a pan-Asian sale that comprised “Avant-Garde” art from China, Japan and Korea. Through 2003 to 2004, Christie’s incorporated contemporary Chinese art into their sales alongside Chinese twentieth century works and contemporary art from Japan and Korea. Sotheby’s, on the other hand, felt especially confident in market demand for contemporary Chinese art in the international style. As Howard-Sneyd acknowledges, auction houses cannot create markets in a vacuum.10 However, their nimble business structures and fluid cash flow enables them to respond quickly to changing market demand. Thus, in response to a rapidly developing market shift, Sotheby’s inaugurated both a new auction category and department to focus on this genre of art.

A “major force” driving collector awareness of contemporary Chinese art, according to Howard-Sneyd, was its display at the prestigious China Club in Hong Kong which was frequented by many wealthy expatriates and visiting businesspeople. Owned by socialite businessman David Tang, the incorporation of contemporary Chinese art at the Club was influenced by Tang’s friend and art advisor, the Hong Kong based dealer and curator Johnson Chang.11 Both men held a passion for contemporary Chinese art and were determined to promote the artists both in Hong Kong and internationally and they were prepared to use multiple vehicles to achieve this.

I think that what Johnson Chang did with David Tang to form this collection and to present it in this quirky, delightful, charming, fascinating, fun way that people got used to being amongst it, was to me, the single most important element of this whole market development.12

Indeed, the global appetite for China was growing rapidly and, for Sotheby’s, the proximity of Hong Kong to China provided a heightened awareness of looming opportunity: “one of the reasons we decided that it was worth going ahead was, we sat in Hong Kong, we heard about China every day. It was very clear to us at that moment....we could feel this juggernaut coming down. We could hear the rumbling.”13

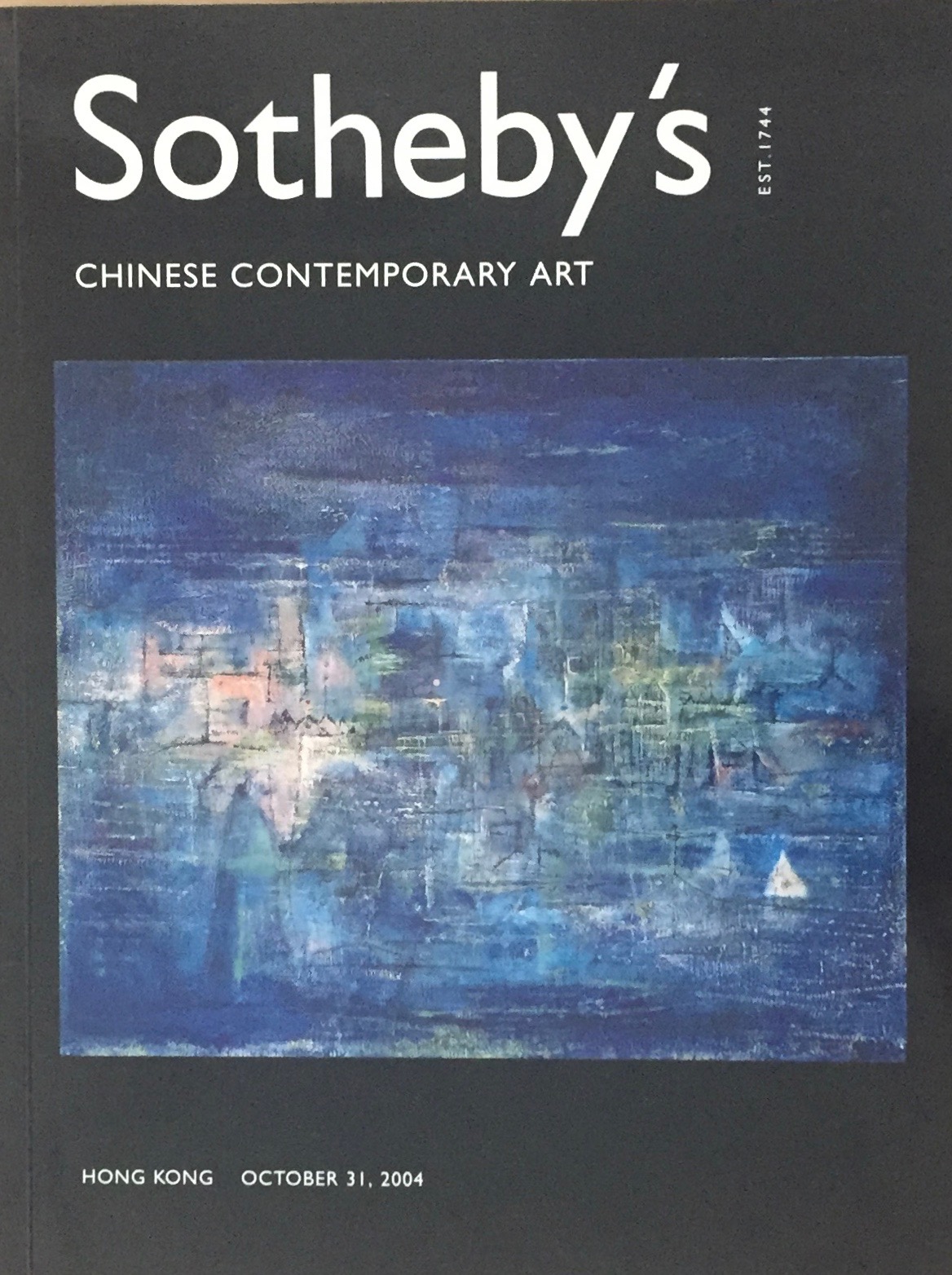

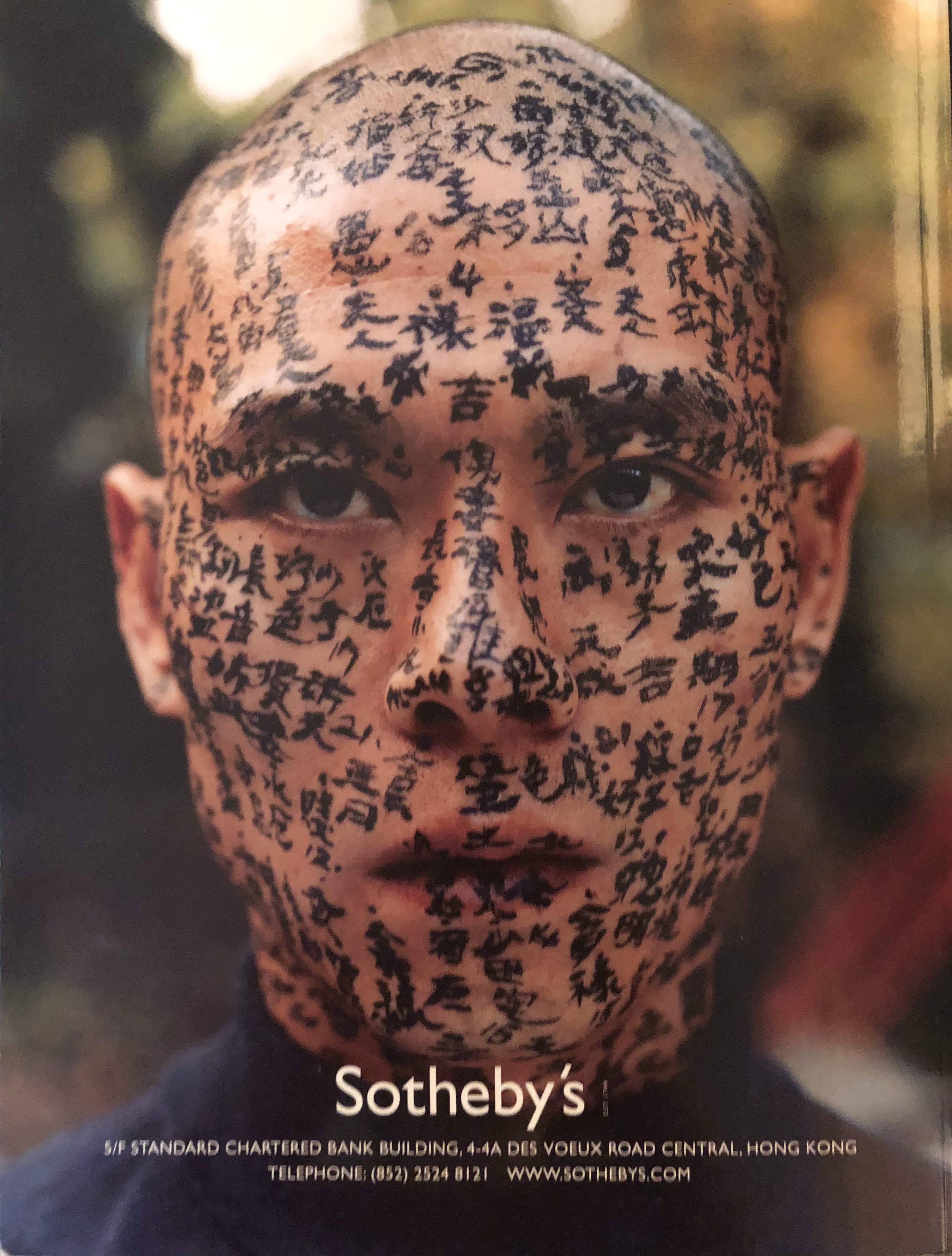

The subtle but significant shift in approach and attitude of Sotheby’s to the fifty artworks offered for sale is revealed in the catalogue cover design for their inaugural auction of Contemporary Chinese Art. In marketing terms, the “real estate” of the front and back catalogue covers is carefully allocated by auction specialists to promote prized artworks that represent auction highlights, often in terms of both rarity and price. The covers for Chinese Contemporary Art demonstrate that whilst Sotheby’s was excited by the new market developments, they still exercised caution. This shift in terminology corresponded to recent success for the multi-national auction houses in both New York and London for contemporary art, whereby the definition of contemporary aligned with the art historical definition of a work produced from 1970 onwards. For Chinese art, this definition is closely aligned with a group of artists that emerged after the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1978. Nevertheless, despite the title of the sale, the front cover of the catalogue depicted lot number 326, an oil painting by post-war abstractionist Zao Wouki titled Engulfed Town and dated 1954 (see fig. 1). On the back cover, however, was lot number 304, a photographic work by Zhang Huan, one of a series of nine works titled Family Tree that depict the incremental obliteration of the facial features of the artist as they are covered in black ink calligraphy (see fig. 2).14 At an auction estimate of HKD200,000 - 250,000 this work was a mid-priced lot within the total auction offering. However, the striking visual image had a clearly contemporary aesthetic with a nod to “Chineseness” through the reference to traditional Chinese ink practice. Indeed, the auction catalogue covers clearly reflected the auction house approach to this new market. The fifty/fifty split of traditional and contemporary aesthetic on the covers mirrored the same split of content for the auction. Specifically, twenty-five lots were by twenty-one contemporary artists the remaining twenty-five were by sixteen artists working in a Modern, traditional style.

Fig. 1: Catalogue front cover depicting Lot 326, Zao Wouki Engulfed Town, 1954. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's Inc. © 2004.

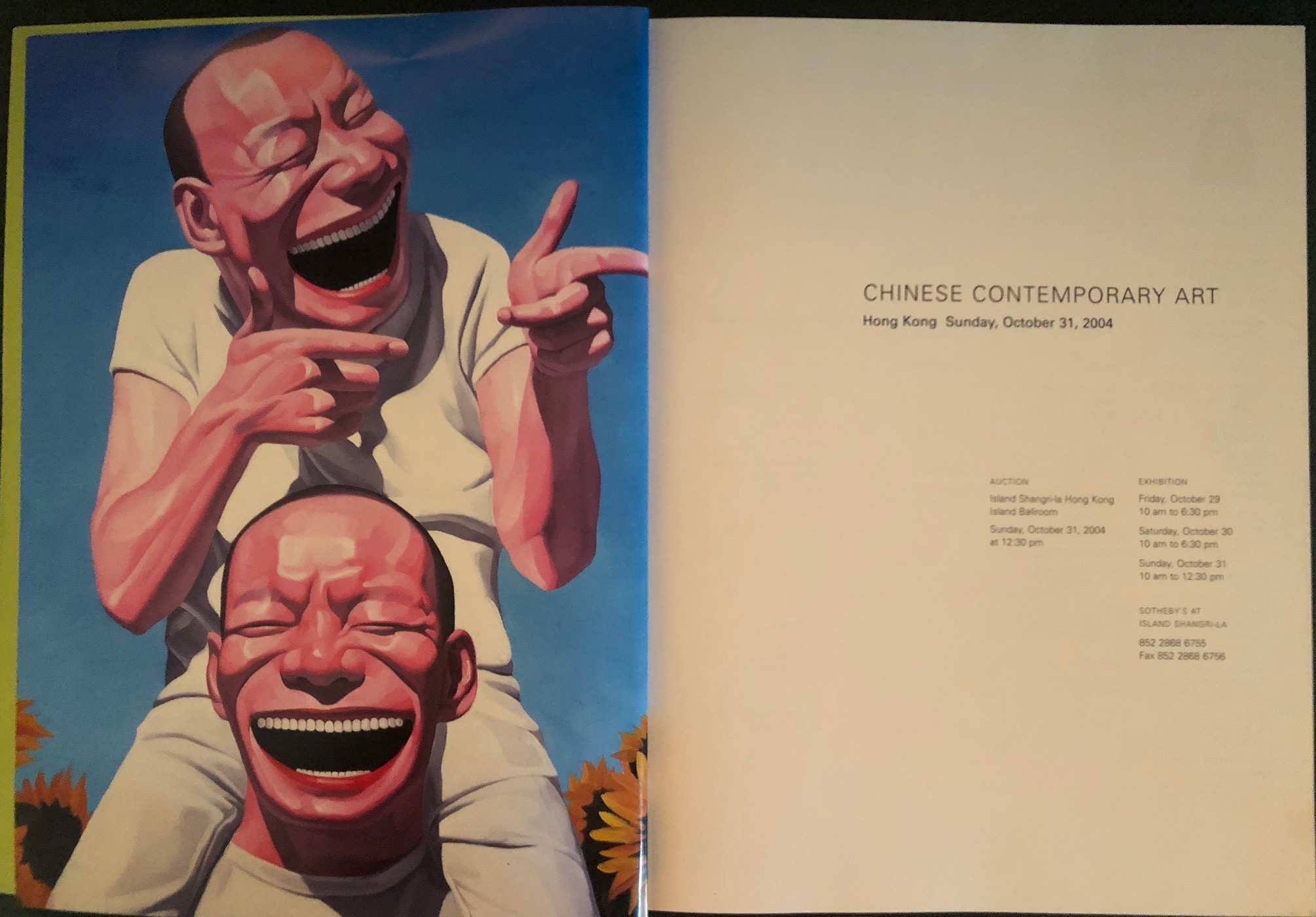

The layout of the catalogue told another story. The interior cover pages focussed exclusively on the contemporary lots with a cropped image of Lot 313, Yue Minjun’s Sunflowers, 2003, positioned opposite the sale information page (see fig. 3) and multiple details of the contemporary lots on a double page spread before the opening lot. Furthermore, the first fifteen lots of the sale were artworks in the international contemporary idiom. Throughout the remainder of the catalogue, the international style works were interspersed with those in the traditional style thereby providing a visual conflation of these two genres whilst seamlessly transitioning between the two as the auction progressed. Potential buyers of the latter were able to view the market response to the former as they sat in the saleroom. Holistically, the Sotheby’s catalogue layout was a clever response to the market adaptations that the auction house understood and wanted to expand. Through the strategic layout of lots within the auction catalogue, Sotheby’s could shift and coax buyers from one market segment to another.

Fig. 2: Catalogue back cover depicting Lot 304, Zhang Huan Family Tree, not dated. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's Inc. © 2004.

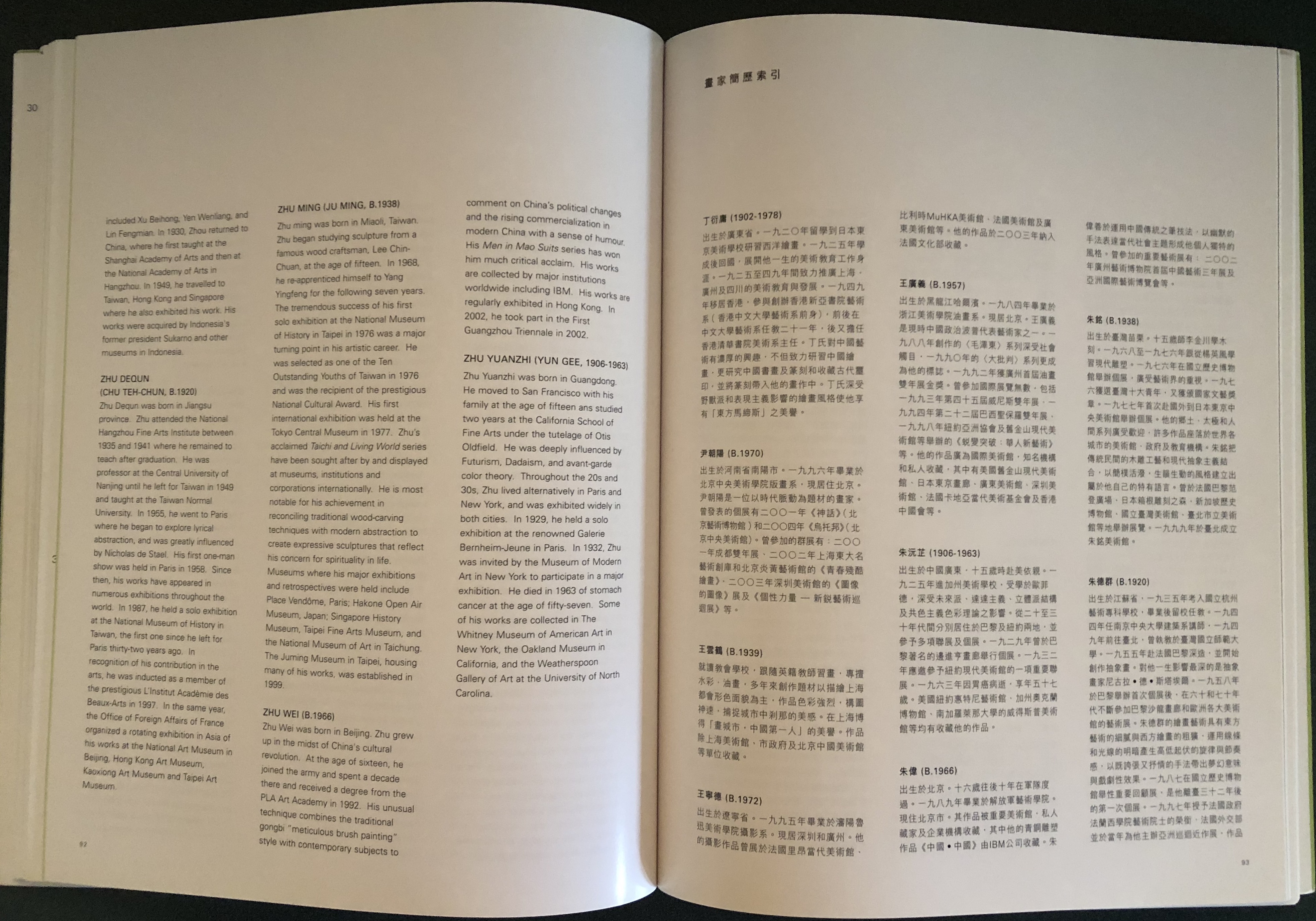

The captions for each lot provided basic artwork information: artist, artist dates, title, year of production, medium, edition number where relevant and size. No specific provenance (history of ownership) was supplied for the majority of the lots and there was none for any of the artworks in the international contemporary style. Instead of provenance to evidence the source of the artworks, the catalogue entries documented quotes from artists, exhibition histories, literature references and biographies that alluded to reputable representation and consecration through other contexts. Biographical information on the artists was collated at the back of the catalogue in a twelve page section of brief summaries, averaging 100 to 200 words, first in English and then in Mandarin (see fig. 4). For the contemporary Chinese artists, the biographies noted educational history and then focussed on the artist’s participation in notable exhibitions, either museum or temporary biennales, primarily in the West.

These biographies revealed that sixteen of the twenty-one artists working in the international contemporary style had featured in prominent exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art outside Mainland China throughout the 1990s. Examination of the curation and promotion of these exhibitions exposes a tight network of diverse cultural mediators who disseminated the practice of this select group of contemporary artists from China via multiple exhibition platforms across the globe. The primary mediators to whom the weight of this translocation points are curator/dealer Johnson Chang, Chinese curators Gao Minglu, Wu Hung and Li Xianting and two Swiss men – collector Uli Sigg and curator, Harald Szeeman.

A Hong-Kong based dealer, Johnson Chang, played a pivotal role in promotion of contemporary Chinese art practice as curator/co-curator of several key international exhibition platforms; moreover, he orchestrated his exhibitions to travel to multiple museums worldwide thereby expanding the global footprint for a small group of artists and their artworks. Chang’s key curatorial ventures in the 1990s included the seminal 1993 exhibition China’s New Art: Post 1989 in Hong Kong, of which reconfigured versions were mounted in Australia, Canada and the USA. In 1995, Chang co-curated two collateral exhibitions of Chinese artists at the Venice Biennale; in 1994 and 1996 he co-curated special sections of contemporary Chinese art for the Sao Paolo Biennale and his co-curated exhibition Reckoning with the Past travelled from Scotland to England, Portugal and New Zealand. Furthermore, Chang co-curated Paris-Pekin, an exhibition of select works from the private collection of an early supporter of the Chinese artists, Baron Guy Ullens. Through these exhibitionary platforms, Chang helped to provide exposure of ten of the twenty-one artists featured in the sale.15

Fig. 3: Catalogue Frontispiece depicting Lot 313, Yue Minjun Sunflowers 2003. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's Inc. © 2004.

Key cultural mediators for the dissemination of contemporary Chinese art outside Mainland China included those who had trained and worked with the artists in the Chinese academies during their student years in the 1980s. Once located outside China, these passionate supporters of the “avant-garde” artists were able to use their skills and network to generate opportunities to promote the artists in the West. Chief Curator of the seminal 1989 Beijing exhibition China/Avant Garde, Gao Minglu was prominently positioned to facilitate exhibitionary opportunities as a curator through his scholarly base in the USA. In particular, his 1998 exhibition Inside Out: New Chinese Art held at the Asia Society and PS1 Contemporary Art Centre, New York, was the first major exhibition of contemporary Chinese art in the United States displaying works by sixty artists. Gao’s exhibition assumed even greater canonical weight with the cancellation of the contemporary section of the simultaneous State-sponsored exhibition China: 5000 years at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; it is highly likely that the Chinese government would have selected a completely different group of artists to represent contemporary art practice in China. Participation in Gao Minglu’s Inside Out: New Chinese Art is specifically mentioned in the biographical summaries of five artists in Sotheby’s auction.16

Fig. 4: Catalogue Artist biography entries, English & Mandarin. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s Inc. © 2004.

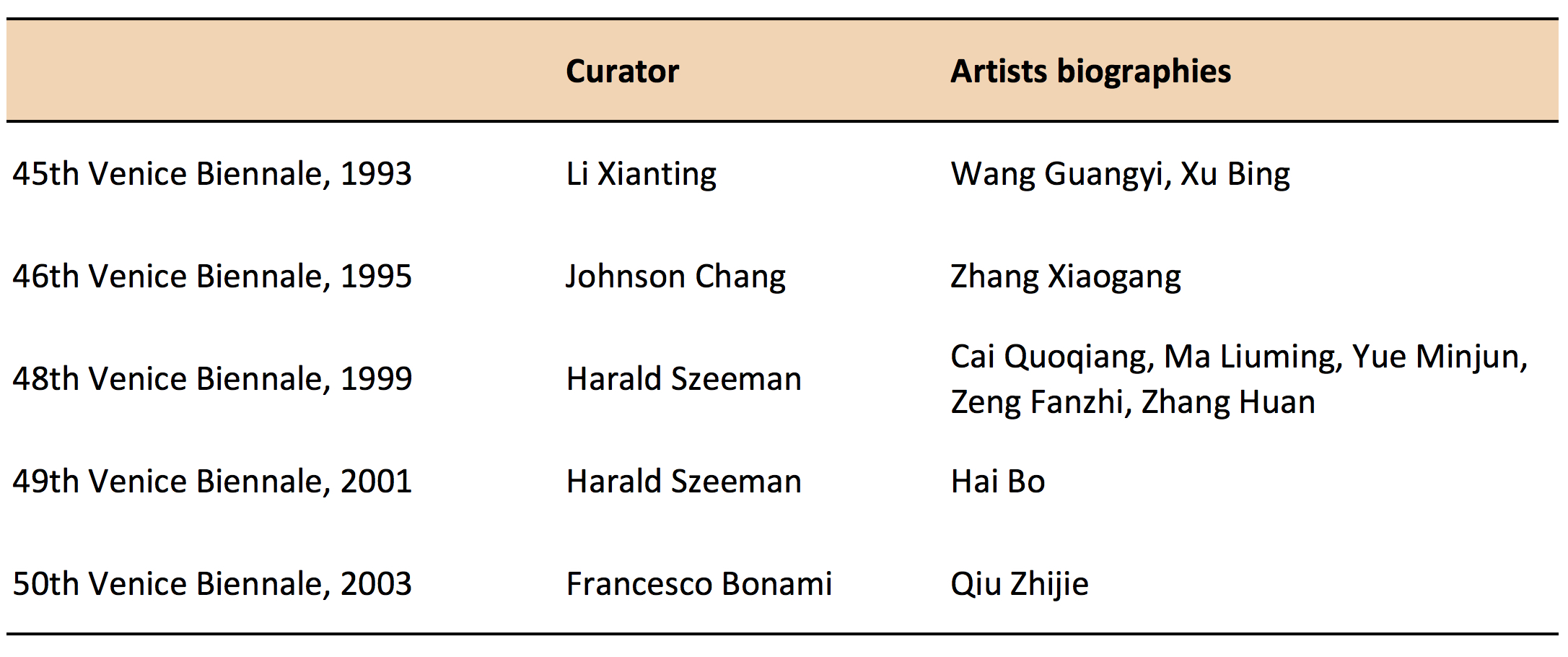

The exhibition with the greatest consecratory power in terms of critical and economic value is, arguably, the Venice Biennale. With its multiple platforms of national pavilions, prominently curated exhibition through the Arsenale complex and extensive collateral programme, the Venice Biennale offers artists exposure to the highest calibre of curators and collectors. Once again, inclusion of contemporary Chinese artists was achieved through a tight-knit group of mediators from a diverse background but united in their determination to expose contemporary Chinese art in the West. In 1993, Beijing-based curator Li Xianting simultaneously co-curated the inclusion of Chinese artists into the Venice Biennale as well as Johnson Chang’s China’s New Art: Post 1989 at the Hong Kong Arts Centre.17 In 1995, Chang himself co-curated two collateral exhibitions in Venice. 1999 was a pivotal year when curator Harald Szeeman curated twenty Chinese artists into his Venice exhibition after being introduced to their work by passionate collector, and fellow Swiss, Dr Uli Sigg. Two years later, Szeeman continued to include contemporary Chinese artists in his Venice Biennale exhibition. In total, ten of the twenty-one contemporary artists included in the auction had participated in an iteration of the Venice Biennale, the most prestigious Western exhibition offering artistic consecration (see Table 1). Thus, there was a very high likelihood that prospective collectors of international contemporary art would have had a familiarity with these artists included in Sotheby’s inaugural sale.

Table 1. Participation of artists in Venice Biennale, iterations as noted in catalogue biographies.

Exhibition histories in the artwork captions of the auction catalogue highlight a clear shift in the international exposure of contemporary Chinese art from museum exhibition to commercial support and promotion from the late 1990s onwards. Once again, the innermost circle played their part and shifted seamlessly between institutional and commercial opportunities. Moreover, exposure of a younger generation of artists resulted in the inclusion of new media art, particularly photography, which appealed both aesthetically and financially to a new audience.

A prominent exhibition that featured as reference for three of the lots in the sale was Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China, co-curated by art historian Wu Hung and curator Christopher Phillips.18 Wu Hung had graduated with an MFA from the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) Beijing in 1980 and moved to Harvard shortly thereafter to complete his PhD in art history and anthropology. A prolific scholar, critic and curator, Wu’s influence expanded after 2000 as he began to curate and write for both commercial and museum exhibitions. In 2002, Wu was appointed Consulting Curator for the Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago. Two years later he was co-curator of Between Past and Future: New Photography and Video from China which opened at the International Centre of Photography, New York, before continuing to the Smart Museum and including the prestigious Victoria &Albert Museum, London, on its itinerary. This exhibition opened five months prior to Sotheby’s auction and heralded an exhibitionary shift to more nuanced exposition of contemporary Chinese art, in this case focussing on new media, particularly photography, which had become an important tool for artists in China to document performance as well as a medium in its own right.19 Whilst these exhibitions had a short lifespan in terms of exposure of artworks to an audience, their longevity endured through the comprehensive catalogues which also provide a platform for education and interpretation through essays written by cultural mediators. Wu’s exhibition featured as prominent exhibition history in the captions for lots 301, Hai Bo Three Sisters, 304 Zhang Huan Family Tree and 306 Qiu Zhijie Tattoo II.

According to Howard-Sneyd, he and his specialists sourced the contemporary lots from a broad network of expatriate workers who had purchased the artworks from local galleries whilst living and working in Hong Kong.20 Lot 310, Zhu Wei Sunflowers No.11, notes an illustration reference to a Plum Blossoms gallery text in 2000. Plum Blossoms had been established in Hong Kong in 1987 and initially focussed on ancient Chinese textiles with furniture, porcelain and art as subsidiary offerings. The gallery increasingly focussed on emerging Chinese artists during the 1990s in response to the growth of market interest in this genre. Whilst Sunflowers No.11 is not dated, Plum Blossoms held a solo exhibition for Zhu Wei in 2000, which was the fifth solo show for the artist at the gallery subsequent to exhibition and representation since 1993.

Within China, a small handful of commercial galleries had emerged in the 1990s, almost exclusively servicing an international market of collectors, as there was little government or public support for this genre of art in China at the time.21 Lot 314, Zheng Fanzhi Mask Series No.1, 1996, notes illustration in Zheng Fanzhi 1993-1998 produced by Courtyard Gallery. Founded in 1996 by lawyer and collector Handel Lee, Courtyard Gallery was located in an historic building adjacent to the Forbidden Palace in Beijing. The gallery space was located beneath a restaurant and cigar divan in an attempt to integrate art into a broader living experience targeting a wealthy local and international elite. The four and six year time differences between the gallery exhibitions of the Zhu Wei and Zheng Fanzhi artworks and the auction date suggests that it is very likely that these paintings were being offered by a private collector using the auction as a secondary market platform. However, due to the small market for contemporary Chinese art at this time, it is also possible that the galleries, or representatives of the artists, consigned them in a primary market capacity.

A commercial exhibition reference was also noted for Lot 350, Sui Jianguo’s Made in China. The catalogue entry notes that these (now iconic) sculptures of dinosaurs were “Edited by Galerie Loft”.22 This Paris-based gallery began to develop a focus on contemporary Chinese art from 1999 when Jean-Marc DeCrop became a business partner, having been a minority shareholder in Johnson Chang’s Hanart Taipei from 1995. 23 DeCrop went on to be co-curator alongside Chang for Baron Guy Ullen’s 2002 exhibition Paris-Pekin. DeCrop’s shift from Hong Kong to China was indicative of a broader movement of artists and mediators in the early 2000s. As the market for contemporary Chinese art expanded, participants in the market shifted around the globe in order to maximise their opportunities.

A further vehicle for consecration in the international contemporary art market was, and still is, the prestigious Swiss art fair brand – Art Basel. The fair’s competitive selection criterion limits gallery participation, thereby conveying a symbolic imprimatur of market significance to both exhibiting galleries and artists. Two of the first gallerists to exhibit contemporary Chinese art in this forum in the early 2000s both had a Swiss connection – Urs Meile and Lorenz Helbling.24 Hai Bo’s biography in the auction catalogue noted representation at Art 32 Basel in 2001. This was under the auspices of Art Beatus, a Hong-Kong based gallery, whose Vancouver branch was directed by esteemed Chinese curator and scholar, Zheng Shengtian. However, participation was no guarantee of sales as art fair visitors struggled to comprehend contemporary Chinese art within an international contemporary context.25

The multi-national auction houses did not have to move – they had the advantage of a global footprint of auction rooms and were able to swiftly translocate supplies of artworks to locations which could maximise potential demand. For their inaugural sale, Sotheby’s was able to take advantage of the foundations of the market in Hong Kong to create and add economic value by carefully selecting and translocating artworks from around the globe to this location. This strategic selection process is evident in the variety of media of lotted artworks as well as their production dates.

In a reflection of the institutional shift to new media, and as part of a clever lotting strategy, the Sotheby’s specialists opened their sale with eight lots of photography. These artworks in new media immediately demarcated a repositioning away from the oil painting focus of preceding auctions. Furthermore as art objects of a multiple format, these photographic works offered a lower price point in the market with low estimates ranging from HKD18,000 to 120,000. Thus, the opening lots had appeal for a new audience of buyers who already had a familiarity with this medium through the exposure of photography in international contemporary art auctions in London and New York. Moreover, the lots in the sale were able to make direct reference to the Western museum exhibitions in their cataloguing as these exhibitions had featured other versions of the same works. Thus, although the material was new to the market, the auction catalogue signposted familiar symbols of value that could offer reassurance to new collectors.

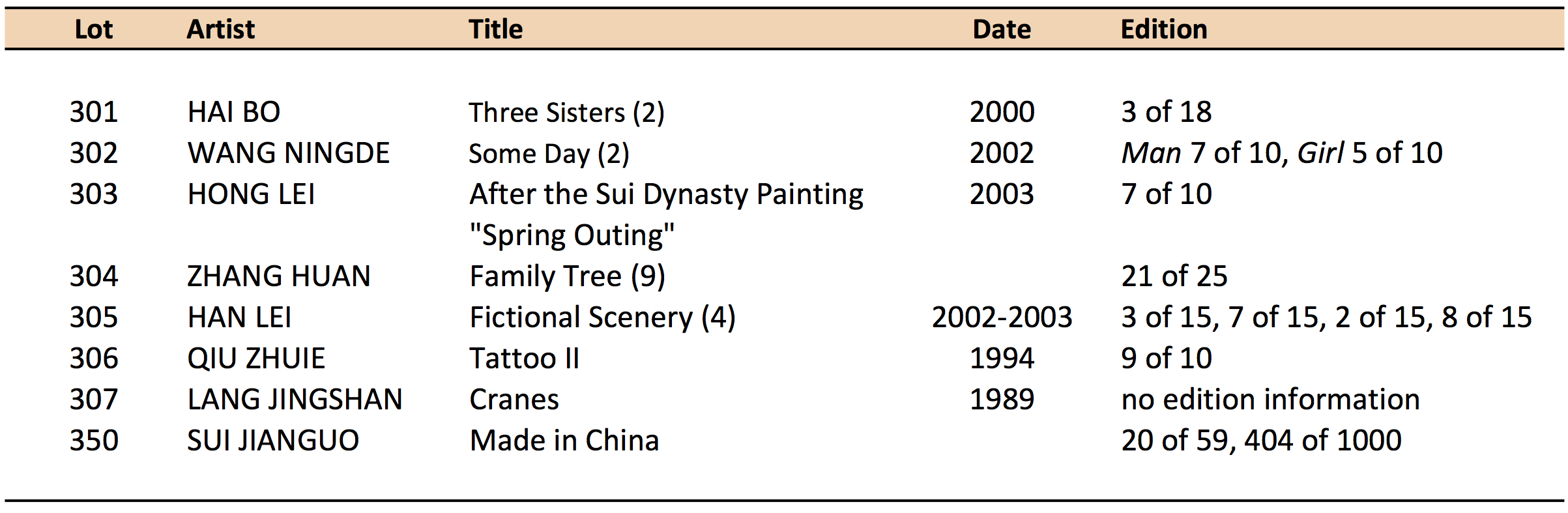

The edition numbers of the photographic and sculptural lots revealed that many of the works were from the mid to latter end of the editions (see Table 2). This would suggest that the previous edition numbers had already sold. Whilst Howard-Sneyd and other auction house specialists have asserted that these lots were sourced from the secondary market, it may be that these lots were recent purchases and/or were possibly sourced from the artists themselves through the auspices of the cultural mediators. However, further analysis of the dates of production of many of the lots of contemporary Chinese art in this sale are extremely recent. It is therefore reasonable to presume that in respect to assembling this inaugural auction, Sotheby’s proximity to the source of the artworks in terms of the very short time that these art works had been in the hands of collectors, could be considered primary market transactions.26

Table 2. Edition numbers of photograph and sculpture lots.

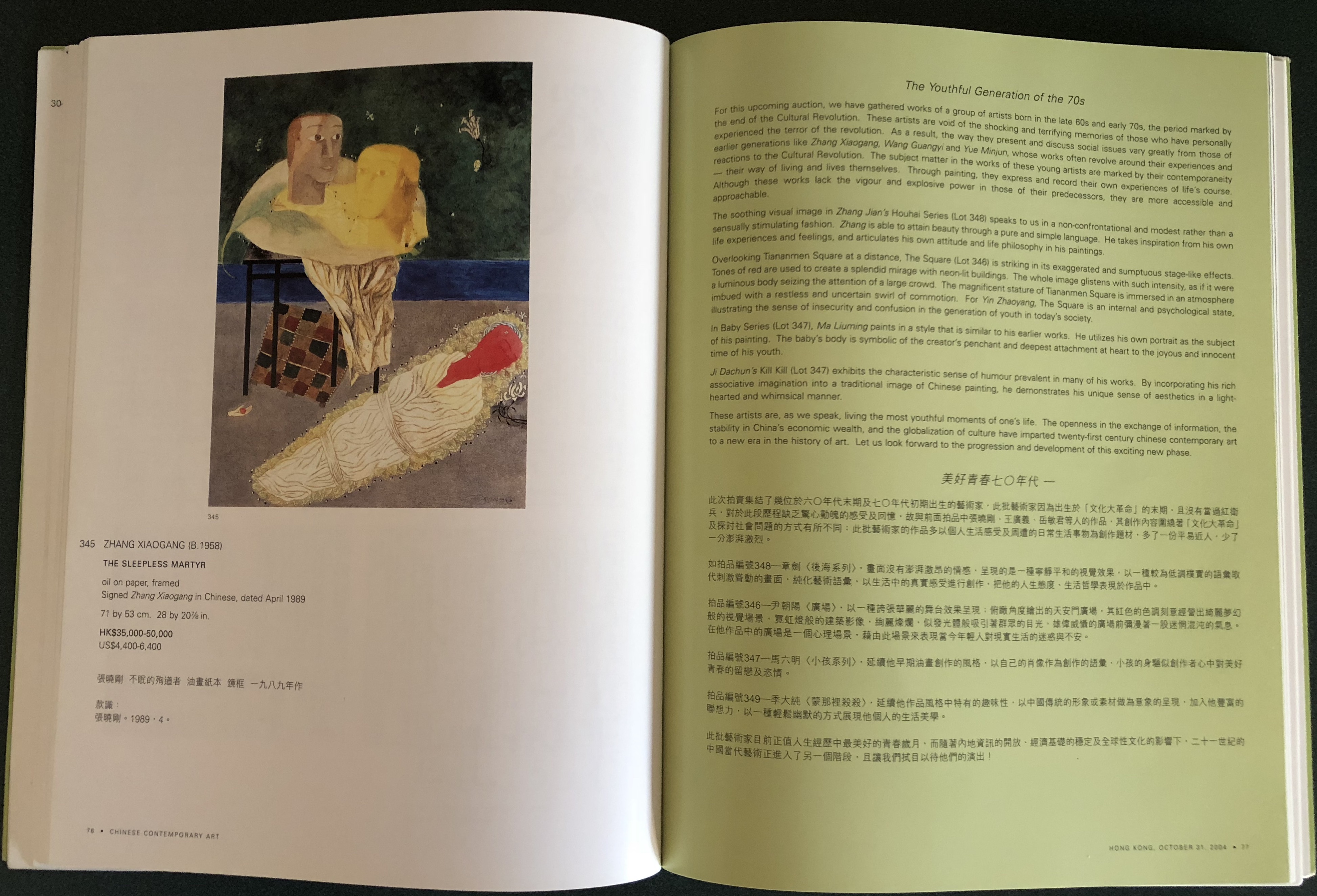

A special section of four artworks (lots 346 to 349 inclusive) were strategically located near the end of the auction under a title The Youthful Generation of the 70s (see fig. 5). Reference to the biographies of three of these four artists indicated that these artists had no previous exposure outside Mainland China. Instead, an introductory essay to the section which briefly introduced the four artworks acknowledged the emerging status of these artists both in terms of age – “these artists are...living the most youthful moments of one’s life” - and the art market – “...a new era in the history of art. Let us look forward to the progression and development of this exciting new phase.” The inclusion of these works signalled a strategy by the auction house to leverage the introduction of new artists to the market by positioning them alongside their recognised, and already consecrated, peers. It would appear that Sotheby’s was using this auction to broaden the acquisition platform away from the limited supply of sought-after artists who had featured in the seminal 1990s exhibitions to a new supply line of artworks by artists who worked in an international contemporary style but without the apparent political critique which underlined the appeal of the previous generation “although these works lack the vigour and explosive power...of their predecessors, they are more accessible and approachable.” Thus, in the strategic positioning of these artists and their works in the sale, Sotheby’s was providing its own value consecration, and in the long term was testing the water to expand potential supply of material for future sales. The vast majority of artists included in the sale came with the institutional imprimatur of the Western museums as noted in the biographical details. However, inclusion of these hitherto unknown artists signalled a consecration through alignment with their artistic peers as well as under international brand Sotheby’s.

Fig. 5: Catalogue essay ‘The Youthful Generation of the 70s”, adjacent to Lot 345, Zhang Xiaogang The Sleepless Martyr, 1989. Photograph courtesy of Sotheby’s Inc. © 2004.

Sotheby’s instinct that the auction market was ready to embrace contemporary Chinese art proved to be accurate. The two-day viewing, on Friday 29 and Saturday 30 October 2004, and the auction, on Sunday 31 October, took place in the ballroom of the centrally located five-star luxury Hong Kong hotel Island Shangri-La. According to Howard-Sneyd, although the sale was allocated just one specialist – Evelyn Lin – the whole Hong Kong team supported the sale in terms of promoting it to their client base.27 The result was outstanding: forty-seven of the fifty lots sold (a sale rate of ninety-four percent) and, of these, all of the contemporary lots sold. In financial terms, the auction achieved HKD22,964,600 against a low estimate total of HKD12,672,000, therefore almost double the auction house expectations. Furthermore, of the contemporary lots, eighty-eight percent sold for higher than the quoted high estimates, indicating that there was multiple, competitive bidding for the majority of these artworks.

The auction house was delighted with the result having been vindicated in their belief of the strength of the new auction market category. However, one significant observation by Howard-Sneyd, as the auctioneer for the sale, was to have major ramifications for the development of these auctions: he realised that the buyer market for this art in Hong Kong was not Chinese but Western.28 Consequently, through the international footprint of the multinational auction houses, Howard-Sneyd immediately connected with his colleagues in New York and London to discuss the translocation of the Chinese artworks out of China and into a global contemporary art market place, thus setting in train the next stage of development for this auction category of art.

Analysis of the catalogue for this inaugural auction of Contemporary Chinese art provides an insight into the foundational infrastructure upon which the auction house was able to build a collector market. Moreover, the strategic curation of the sale through the judicious selection of material and the careful placement of the lots to generate a dynamic auction environment underlines the significant role that auctions and auction house specialists play in the contribution to the formation of an emerging art market.

By forensically examining the auction catalogue and ensuing exhibition and sale of Sotheby’s inaugural auction of contemporary Chinese art, this paper has revealed the ability of the auction house to shift the target audience of potential buyers from previous auctions. Moreover, interrogation of provenance, exhibition histories and literature references has revealed an integrated and active network of cultural mediators assuming multiple roles of dealers, critics and curators. Finally, the paper has suggested that this auction potentially operated in a primary market capacity thereby denoting an important and pivotal shift in the role of auction houses at this time in the market for contemporary Chinese art specifically, and global art more broadly, particularly as creators of symbolic and economic value for art. It is acknowledged by the author that the timing of the expansion of the market for contemporary Chinese art was integrally connected to a global interest in China at this time, particularly in the lead up to the Beijing Olympics of 2008. However, it is hoped that this research and its methodology can provide a contribution to further research on other emerging markets and the role of auction houses in the global contemporary art world.

Anita Archer is a PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne. The subject of her research is an analysis of the role of the multinational auction houses in developing an auction market for contemporary Chinese art.

1 Julian Stallabrass, Art Incorporated: The Story of Contemporary Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004); Hans Belting, Andrea Buddensieg and Peter Weibel, eds., The Global Contemporary and the Rise of New Art Worlds (Karlsruhe: ZKM / Centre for Art and Media, 2013).

2 Clare McAndrew, Globalisation and the Art Market: Emerging Economies and the Art Trade in 2008 (Helvoirt: TEFAF [The European Fine Art Foundation], 2009), 33.

3 Sociological and art historical studies of nineteenth and twentieth century art worlds have revealed the significance of network connections to grow, develop and sustain art markets. Howard Becker, Diana Crane and Raymonde Moulin have written extensively on the role of a collaborative networks to create “art worlds” whilst more contemporary investigations can be found in the writings of Julian Stallabrass, Hans Belting and Charlotte Bydler.

4 Diana Crane, The Transformation of the Avant-Garde: The New York Art World, 1940-1985 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987), 110.

5 Howard Saul Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

6 A comprehensive analysis of stakeholder positioning and reasoning behind the formation of terminology relating to the artists of the Chinese “Avant-Garde” can be found in Martina Koppel-Yang, Semiotic Warfare: A Semiotic Analysis, the Chinese Avant-Garde, 1979-1989 (Hong Kong: Timezone 8, 2003).

7 Olav Velthuis, Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art, Princeton Studies in Cultural Sociology (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 82,96.

8 In April 2003, Sotheby’s offered Xu Bing’s New English Calligraphy Mao Zedong’s Quotation (estimate HKD70,000-100,000, sold HKD96,000) and Cai Guo-Qiang’s Sinking and Rising, Project for Extra-terrestrials No.27 (estimate HKD400,000-600,000, sold HKD540,000). In April 2004, they offered Cai Guo-Qiang’s Fetus Movement Project for Extra-terrestrials No.5 (estimate HKD120,000-160,000, sold HKD288,000).

9 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author, personal interview, London, 25 April 2016.

10 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).

11 Johnson Chang (Chang Tsong-zung) opened his first gallery in Hong Kong in 1977 specialising in traditional Chinese art. In 1983, he opened a second space entitled Hanart TZ which focussed on the “avant-garde”. Sir David Tang (1954-2017) was founder of the China Club and retail chain Shanghai Tang. He was a funding partner of Chang’s gallery business.

12 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).

13 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).

14 The edition of Family Tree offered for sale in the catalogue is not dated; however, Zhang Huan created this artwork in 2000.

15 Artists in the sale included in the noted exhibition platforms curated by Chang are Cai Guoqiang, Hai Bo, Ma Liuming, Qiu Zhijie, Sui Jianguo, Wang Guangyi, Xu Bing, Zeng Fanzhi, Zhang Xiaogang, and Zhu Wei.

16 Specified in the biographical summaries of Ma Liuming, Qiu Zhijie, Wang Guangyi, Zhang Huan and Zhang Xiaogang.

17 A highly respected editor/critic/writer, Li Xianting was a co-curator of China/Avant Garde with Gao Minglu. A government ban on his role as editor after 1989 caused Li to focus on his role as a curator and promoter of “avant-garde” Chinese artists.

18 Christopher Phillips, curator, International Centre of Photography, New York.

19 For in-depth analysis of the development of exhibitions of contemporary Chinese art in the West, see Britta Erickson, The Reception in the West of Experimental Mainland Chinese Art of the 1990s, in Wu Hung and Peggy Wang, eds., Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2007), 357-362.

20 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).

21 Multiple interviews with contemporary art gallerists in Hong Kong and China at this time quote dealers noting the lack of collectors from mainland China. Courtyard Gallery employee Pi Li noted of the year 1998 that “As Uli Sigg was at the time the only client of the gallery.......” Franz Kraehenbuehl, Barbara Preisig and Michael Schindhelm, Interview with Pi Li (Zurich, CAS Contemporary Chinese Art I Executive Education on Global Culture, 2015), 70.

22 A supersized version of this sculpture stands in the forecourt of the Ullens Centre for Contemporary Art, 798 District, Beijing.

23 Galerie Loft was founded in 1985 by Jean-François Roudillon with a focus on international emerging artists. DeCrop was a former French cultural attaché to Paraguay who relocated to Hong Kong in 1993.

24 Galerie Urs Meile had operated in Lucerne, Switzerland, since 1992 and began to promote contemporary Chinese art after introductions to artists, including Ai Weiwei, from Swiss collector Uli Sigg in the late 1990s. Swiss-German art historian and Sinologist Lorenz Helbling began his career in contemporary Chinese art at Plum Blossoms Gallery in Hong Kong, before moving to Shanghai in 1995. Helbling opened his gallery ShanghART in 1998 and first exhibited at Art Basel in 2000.

25 Lorenz Helbling interview with Barbara Pollack. Barbara Pollack, Chinese Photography: Beyond Stereotypes, in ArtNews, February 2004.

26 The role of the multinational auction houses as primary market for contemporary Chinese art is a key element of investigation in my PhD research.

27 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).

28 Interview of Henry Howard-Sneyd with author (as fn. 9).