ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Alexandra von Przychowski / Esther Tisa Francini

In the example of research at the Museum Rietberg, the history of the art market for Chinese art from the provenance perspective presents itself as a history of collections. The article will demonstrate that an investigation into early art collectors can provide answers to the question when, how and in which context art works from China were appreciated, exhibited and sold. In the substantial history of art transfers, the era of National Socialism is one period that forms a focus of provenance research, but excavations, missions, scientific field trips, adventurer travels and many other contexts are also included in the wide definition of provenance research at the Museum Rietberg. Initial research on the von der Heydt collection found that Eduard von der Heydt was advised by major, mainly German specialist in Chinese and Asian Art at the time. Besides the von der Heydt collection, many other early collections of Asian art have come into the holdings of the museum since its inception, for example those of Mary Mantel-Hess, Gret Hasler, Otto Fischer, Herbert von Dirksen, and Herbert Ginsberg. The history of collecting Asian art provides valuable insights into the art market. A more profound cross-reference of the collection histories, provenance and reception history will be a task in the future to gain a better understanding of the art market in the first half of the twentieth century.

The fascinating and extensive collection of Eduard von der Heydt (1882-1964), the founding collector of the 1952 established Museum Rietberg prompted the Museum to set up a project into the provenance of the objects in its collection. The project was contextualised by studies into the collector’s intriguing biography, multi-faceted relationships and outstanding and quite unique taste for art from different cultures and religions. Starting in 2008 – ten years after the Washington Principles about Nazi-looted art1 – with research into 1,600 objects from around the world, the aim was to identify whether any Nazi-looted art was part of the holdings. This research formed the basis of compensating the heirs of the Jewish owners of four Chinese art works as well as an exhibition in 2013 about Eduard von der Heydt and his collection with an accompanying catalogue.2 The provenance of the objects in the collection is also published online as far as the current state of research is available.3 Of course there are still many gaps, and sometimes the present archival research yields very little information, but provenance research is inevitably an ongoing process. Research into dealer sources still needs to become accessible for research, especially with regard to German ones such as Edgar Worch, Theodor Bohlken or Ernst Fritzsche, considering circumstances during the 1930s and 1940s. Another area that requires further exploration are the activities of C.T. Loo. In the example of research at the Museum Rietberg, the history of the art market for Chinese art from the provenance perspective presents itself as a history of collections. The article will demonstrate that an investigation into into early art collectors can provide answers to the question when, how and in which context art works from China were appreciated, exhibited and sold.

Only a few objects of the Chinese art collection of the Museum Rietberg can today be traced back to China, but to begin with, this was not included in the project scope.4 Yet provenance research should be understood in a broader sense, that means covering the entire object history. The so called “provenance turn” (Christoph Zuschlag) was initiated by the questions raised by Nazi-looted art, but meanwhile colonial histories and other contexts of possible injustice have also entered the discussion.5 As a result, provenance research at the Museum Rietberg continues, covering a wide range of research areas. In a museum for non-European art, the attention to provenance must by necessity include a range of academic disciplines. Therefore – even if the focus on Nazi era provenance always needs to be present – the object of this kind of research is a sustainable documentation of the paths taken by the art works, be it paintings, sculptures, textiles or objects made from other materials, following their history from the point where they came into being to their discovery and re-evaluation until their arrival and reception in today’s location.

In the substantial history of art transfers, the era of National Socialism is one period that forms a focus of provenance research, but excavations, missions, scientific field trips, adventurer travels and many other contexts are also included in the wide definition of provenance research at the Museum Rietberg. These facts, figures and histories often remain untold by museums: the collection history, the context of the discovery of an object, its exportation and transportation, the reception of different genres of art, the appreciation and reception influenced by the “Zeitgeist” and of course the individual biography of the actors involved in translocations in art, and their multiple identities as archaeologists, dealers, curators, or collectors.6

The aim of the Museum Rietberg’s transparency policy is to regard provenance as an alternate history of art, because the historical background provides us with more insight into the objects, their role on the art market and entangled histories. Provenance research leads to a deeper knowledge of collection history, art market, taste-building, the history of sciences and cultural politics.7 It contributes also to the politics of a “shared heritage”, together with the “digital turn” – digitisation of the collections, catalogues and archives to make objects virtually accessible for a greater public. Of course, the physical whereabouts of the collections, once displaced, looted, sold and variously valued, transformed in their function and meaning, are today discussed politically, in a globalised world. As the – very much academic – post-colonial debates reach the museums, these institutions have to decolonise themselves, through cooperation, transnational research and of course provenance research and restitution. But provenance research should not be equated with restitution; restitution can be a consequence of provenance research.8 Maybe even more relevant are transnational co-operations within research, exhibition and knowledge transfer. On world art, the global art world must work together.

Some recent publications and initiatives in the field of collection history of Chinese art are worth mentioning in this context. There are of course museum and collection histories, dealer biographies, memories of private collectors and comprehensive studies in academic history.9 An early research project was CARP, Chinese Art – Research into Provenances. The starting point was the Burrell Collection in Glasgow where records relating to dealers and collectors who specialised in Chinese art during the first half of the twentieth century were documented.10 Essays about John Sparks, William Burrell, Ton-Ying & Co and Alfred Ernst Bluett provide a large amount of information which is relevant for other collections and art trade history at that time. Since 2008, the Freer Sackler Galleries have also been researching the provenance of their collections in greater depth. Apart from the online presentation of the collection they are also publishing dealer and collector biographies which contain important information for cross-reference with provenance.11 In 2016 the Berlin conference “All the Beauty of the world. The Western Market for non-European Artefacts” also included papers relating to the Asian art market, and in 2017 a follow-up workshop with a specific focus on Asian art was organised, also in Berlin.12 In 2018, the celebration of the centenary of the Asian Art Society in the Netherlands brought about a more profound understanding of the formation of many private and public collections in the Netherlands, but also in Europe and the United States.13

Collecting history and provenance research are entering more deeply into museum work and academic research. They provide useful information to understand and analyse the art market, the translocation of the art works and their reception in the Western world.

The Chinese art collection of Eduard von der Heydt contains about 300 objects, mostly sculptures, reliefs, figures in stone, covering a wide range of dynasties. Only a few paintings have found their way into the collection of the Museum Rietberg.14 Von der Heydt never travelled to the countries of the origin of his art works but bought from the major dealers and was regularly advised by the most prominent art historians and curators at the time. His interest and initiation to Chinese art were prompted by Arthur Schopenhauer’s lecture “Upanischaden”. For Eduard von der Heydt, Chinese art meant especially Buddhist art. He never really took to decorative art works such as ceramics.

Fig. 1: The private museum Yi Yuan of von der Heydt, Amsterdam, around 1921-1924

Unknown photograph, @ Museum Rietberg.

In 1920 von der Heydt bought the collection of the sinologist Raphael Petrucci from the Amsterdam art dealer Aäron Vecht. It consisted of more than 400 works of varying quality, mostly paintings and wooden sculptures from China and Japan. This acquisition stirred his passion for collecting, and within five years most of the key works for which he would later become famous were already in his possession. He bought Chinese sculptures from leading dealers in Paris, London and New York. Between 1921 and 1924, his collection was on display at his home in Amsterdam. This private Museum was called Yi Yuan (fig.1). Karl With (1891–1980) was the first curator of the von der Heydt Collection.15 He had expanded his knowledge of world art while working with Karl Ernst Osthaus (1874–1921), the founder of the Museum Folkwang in Hagen. Karl With advised von der Heydt on the development of his collection and in 1924 published its first catalogue. He later became the director of the Museum for Applied Arts in Cologne, where he curated several spectacular avant-garde exhibitions. In 1933, this led to his downfall and summary dismissal. In 1937/38, von der Heydt commissioned Karl With again to prepare an inventory of his substantial collection. Today, this is the document where a study of the objects’ history has to begin. In 1939, With emigrated to the United States.

Alfred Salmony (1890–1958) was another early advisor for the von der Heydt Collection. From 1920 to 1933 he was a curator at the Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne. There he was responsible for the first major exhibition in Germany of Asian art in 1926 where von der Heydt was also a lender. After Salmony was dismissed by the Nazis in 1933, he emigrated to France and in 1934 to the United States, but he remained in contact with von der Heydt until his death and published many articles about von der Heydt’s collection.

The German art historian, founder and co-publisher of Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, William Cohn (1880–1961), wrote the collection catalogue Asian Sculpture in 1932. He, too, was dismissed from his job as curator at the Berliner ethnological museum by the Nazis in 1933, and in 1938 he emigrated to Britain. From 1946 he worked in Oxford where he founded the journal Oriental Art and established a museum for East Asian Art which today is part of The Ashmolean Museum.

Clearly, Eduard von der Heydt was advised by major specialist in Chinese and Asian Art in Germany at the time. This relationship was nevertheless ruptured in 1933 when nearly all of them emigrated. Von der Heydt still continued to buy art, even under the limitations imposed by Nazi cultural politics, where the art market was brought into line and dealers could sell only with official permission. Consequently, provenance research in the von der Heydt collection with the focus on the period 1933-1945 yielded particular insights into the German Art market in East Asian Art after 1933. Dealers such as Theodor Bohlken, Ernst Fritzsche, Edgar Worch, and Otto Burchard directly imported from China at this time but also sold works from German or European collections to museums or other collectors.16 Paul Graupe was the autioneer selling the liquidated firm of Otto Burchard which was part of the “art empire” of Albert Loeske, later owned by Rosa und Jacob Oppenheimer.17 At the subsequent series of auction sales, many museums, dealers and collectors were buying, including von der Heydt. Out of five art works he acquired, four are still in the collection of the Museum Rietberg today, while in 2010 a compensation agreement was reached with the heirs of Oppenheimer as mentioned in the introduction.

Eduard von der Heydt’s main dealer in Chinese Art was without any doubt C.T. Loo.18 The outstanding stone and bronze works of highest quality confirm von der Heydt’s exceptional taste for monumental sculptures. Loo had a highly effective network with intermediaries bringing him the most recently discovered pieces. Of comparable importance for him were Yamanaka Sadajiro and Paul Mellon in Paris and New York.

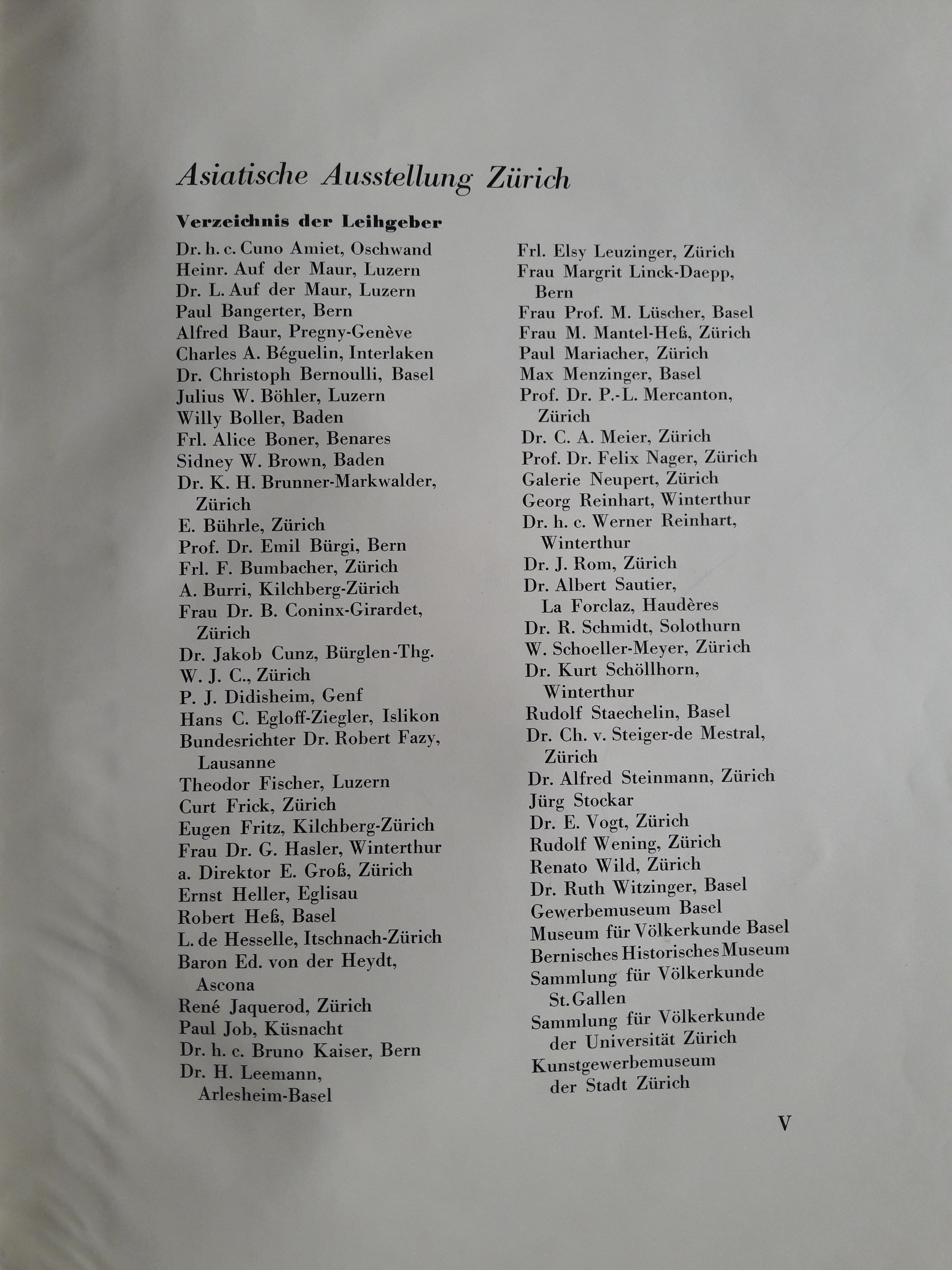

Early private collections of Asian art in Switzerland often ended up later at the Museum Rietberg. These collections were documented in the exhibition of “Asian Art in Swiss Collections” in 1941, held first at the Kunsthalle in Bern and then at the Museum for Arts and Crafts in Zurich. Max Huggler and Johannes Itten, the two directors of those institutions, were both prominent art historians, and Itten later became the first director of the Museum Rietberg. It was an enormous achievement to gather these collections together during the war.19 This exhibition was also the first “product” of the Swiss Society of the Friends of East Asian culture founded in 1939 by Robert Fazy (1872-1956), a lawyer from Geneva, who assumed a leading role in the exhibition organisation, seconded by Max Huggler (1903-1994), and Eduard Horst von Tscharner (1912-1960), the first professor for sinology in Switzerland. To quote from their foreword: “There is no need to justify a comprehensive exhibition of Asian art in Switzerland. Numerous collectors have focused on the art of East Asia for many years. Their understanding and interest in this art may have been sparked by economic relationships which established trade and industry with that continent, while at the same time enabling the direct purchase of valuable pieces.”20 Forty-two lenders contributed to the exhibition in Bern, among them six institutions, and sixty-six at the second venue in Zurich (fig. 2 and 3). Many collections or part of collections found their way into the Museum Rietberg, coming from collectors such as Paul Bangerter, Julius W. Böhler, Willy Boller, Alice Boner, Sidney W. Brown, Eugen Fritz, Gret Hasler, L. de Hesselle, Eduard von der Heydt, René Jaquerod, Elsy Leuzinger, Mary Mantel-Hess, P.-L. Mercanton, Georg Reinhart, Werner Reinhart, Albert Sautier, Rudolf Schmidt, Kurt Schöllhorn and Jürg Stockar.

Fig. 2: Catalogue of the exhibition of Asian Art at the Museum for Arts and Crafts, Zürich, 1941.

It is worth focusing our attention for a moment at two of these early collectors in Switzerland, both of them female: Mary Mantel-Hess (1895-1968) and Gret Hasler (1895-1971).

Heinrich A. Mantel-Hess (1888-1960), was a sinologist and lawyer, who had lived for a while in China with his wife Mary Mantel-Hess. He was the first president of the Rietberg Society between 1952 and 1959, and a member of the acquisition commission of the Museum which at the beginning constituted of a large group of artists, politicians, dealers, art historian and collectors. After his death, his wife took over his position. They both had a friendly relationship with Eduard von der Heydt, who remained still very close to “his” museum until his death in 1964.

Heinrich Mantel-Hess was also a promoter, founding member and vice-president of the Swiss Society of Friends of the East Asian culture. In the Mantel-Hess household, it seems that she was the collector, at least since the 1930s, and responsible for social and artistic events, in a “salon” where Zurich society met. When the Museum Rietberg was founded she bought pieces to bequeath to the Museum after her death. For example, Johannes Itten, the first director, bought a Song vase at Galerie Fischer auction house in Lucerne in 1953 on her behalf which was later donated to the Museum (RCH 2411).

At her death she left forty-four artworks as her legacy: Chinese paintings, Japanese and Chinese vessels and Indian and South-East Asian sculpture. She was a client of René Jacquerod, Pully, one of the most important suppliers for Asian art collectors in Switzerland, but also often bought from a number of Parisian art dealers.21

The city of Winterthur is best known for its collectors’ early interest in Impressionist paintings, but the Reinhart family and others not only had an intensive economic relationship with Asia but also engaged in a cultural exchange. Consequently, Japanese, Indian and Chinese art entered their collections. Gret Hasler came from a Winterthur family, where her father worked for the famous Sulzer, a foundry company which had been an exhibitor at the World Fair in Paris in 1867.

H.F. E. Visser published a notable description of the collection of Gret Hasler (1895-1971).22 Her jade pieces were extremely prominent and could be equalled by few other collections. Today the Rietberg Museum holds only four jade works, but otherwise bronzes, graphic works and arms. Hasler also bought many pieces from C.T. Loo in Paris in the 1950s.

The museum’s Chinese art collection comprises 1,700 objects, even without taking into account permanent loans such as the Meyiyintang Collection. Apart from the three above-mentioned collectors, other collectors with connections to von der Heydt also contributed to the growth of the museum. Several examples will be presented here.

Fig. 3: List of lenders of the exhibition of Asian Art at the Museum for Arts and Crafts, Zürich, 1941.

Fifty-two ceramic pieces in the Museum Rietberg come from the collection of Herbert von Dirksen (1882-1955). The German diplomat, who served as ambassador in Moscow (1929-1933), Tokyo (1933-1938) and London (1938-1939), had early developed a great interest in Asian art.23 On a year-long pleasure trip around the world in 1907/08 he visited Japan for the first time and later described this experience as the beginning of his career as a collector. He probably bought his first pieces of Chinese ceramics during this journey. Even before his long sojourn in Japan he must have accumulated a number of fine Chinese ceramics.24 Some of them were shown in the great exhibition of Chinese art held in Berlin in 1929.

When dispatched to the German embassy in Japan, he used his time for extensive travelling and sightseeing. His periodical circular letters to friends with reports on his experiences were published as a book in 1938.25 In these letters he mentioned several visits to important Japanese collectors.

Dirksen was an active supporter of Asian art in Europe. In 1937 he became chairman of the Society of East Asian Art and began to encourage the organisation of an exhibition on Japanese art from important Japanese lenders in Berlin, realised in early 1939.26

His collection was acquired partly from dealers – he mentions Yamanaka and Hayashi in his letters, we have labels from Spink, Bluett and other on the objects.27 Some pieces were also given to him when he left Japan, and there were probably also diplomatic gifts.

After the war, Dirksen lost his residence in Silesia as well as most of his belongings. Some of his art collection, including his collection of Chinese ceramics as well as his books were later found in Dublin. He donated the books to the Library of the University of Cologne and most of his art collection to the City of Cologne, but he intended to sell his collection of Chinese ceramics. The ceramics were bought by Eduard von der Heydt, with whom Dirksen had a life-long friendship.28 They had met for the first time in Den Haag in 1917 when they both worked for the German Embassy. Von der Heydt mentions the collection purchase in his obituary of Dirksen: “He owned a small, but significant collection of Chinese and Japanese ceramics, but he was forced to sell it after the loss of his properties. The author of these lines suggested the Museum Rietberg in Zurich. He bought the collection for a moderate price and placed it at the Museum Rietberg, where it has found a permanent residence as a sign of Dirksen’s admiration for Zuerich and Switzerland.“29

The Museum Rietberg was also given two groups of objects from the estate of the German art historian Otto Fischer (1886-1948): 285 rubbings and a smaller set of 62 popular prints, acquired in China in 1926.

Otto Fischer is well known as the director of the Museum of Fine Arts (Staatsgalerie) in Stuttgart. While managing the institution from 1921 to 1924, he was able to greatly enlarge the collection of contemporary art. After more and more critical voices rose against his buying and exhibition policy, he left Stuttgart and was appointed conservator and head of the Museum of Art (Kunstmuseum) Basel. At the same time he started teaching at the local university.30

Otto Fischer had studied art history in Tübingen, Munich and Vienna. His most influential teachers were Max Dvorak and Heinrich Wölfflin, the latter became his doctoral tutor. From early on he developed a pronounced interest in Asian art. In 1921 he qualified as a professor with a thesis on Chinese art theory. He later revised this treatise and published it in 1921 under the title Chinesische Landschaftsmalerei (Chinese landscape painting). The book soon became a standard reference work and was reprinted five times: in 1921, 1923 and 1945, and even as a rediscovery in 2013 and 2015.

In 1925 Otto Fischer could satisfy his longstanding desire to travel to China and Japan in order to study art collections and see the famous sights. The journey was financed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. According to Fischer’s biographer Nikolaus Meier it was not unusual to send art historians on semi-academic, semi-political missions. It seems that Otto Fischer was supposed to ameliorate the relationship between China and Germany. After his trip he had to submit a political analysis which was published in 1927.31 During the ten month of his trip, Fischer visited as many art collectors and art dealers, museums and famous sights in Japan and China as possible, though some parts of China remained out of bounds because of political turmoil. A detailed account of the trip was published in 1939 as Wanderfahrten eines Kunstfreundes in China und Japan.32 It seems that the purchase of art objects was neither his aim nor his mission. According to his diary he only bought some souvenirs, as well as books, rubbings and prints.

A subject that held particular interest for Otto Fischer was the history of printmaking. In China, he researched early prints, but much to his regret he couldn’t find high quality prints, neither in libraries nor in antiquity shops. On his survey of print-making workshops he found some “really unsophisticated and charming sheets” of popular prints, as sold for New Year or other seasonal festivities. Fischer bought several of these inexpensive prints, mainly in Suzhou and in Shanxi province.33 But he could not find any of the typical New Year’s prints, since he was travelling out of season from May to October.34

In several places he purchased rubbings of steles or reliefs. In his diary he mentions a number of times that he was able to buy rubbings of local steles in bookshops or temples.35 On some occasions the rubbings were made for him on the spot.36 It seems that Fischer acquired most of the rubbings on his trip to China. Part of his collection of rubbings was exhibited in 1944 in the Museum of Arts and Crafts in Zurich.37

Whether he continued to collect after his return is not known. His biographer Nikolaus Meier notes that he received a large gift of 200 rubbings in Beijing,38 but Fischer’s diary does not mention such a present. The collection of 285 rubbings was offered to the Museum Rietberg by Fischer’s daughter, Hilde Flory-Fischer, and was eventually donated in 1965.

Several years later Hilde Flory Fischer presented the museum with two more objects from the property of Otto Fischer: the fragmented wooden sculpture of a Luohan (RCH 318),39 whose provenance is not known, and a folder with sixty-two popular prints.

Since the 1920s Otto Fischer had maintained a friendly relationship with Eduard von der Heydt. In his treatise Die chinesische Malerei der Han-Dynastie he names von der Heydt as one of the important patrons of his trip to East Asia. In 1928 Fischer introduced von der Heydts collection in the journal Pantheon, and in 1934 he curated an exhibition on Chinese painting from the collection in the Museum for Arts and Crafts in Zürich. When Fischer moved to Ascona after his early retirement in 1938, one of the reasons for choosing his new home was the proximity of von der Heydt on Monte Verità.40

Most of the more than 930 objects of Asian Art owned by Herbert Ginsberg (1881-1962) around 1930 were lost in the Second World War. Thirty-one of the 103 surviving pieces are now in the Museum Rietberg.41

Herbert Ginsberg was a member of the circle of active promoters of East Asian Art in Berlin in the 1920s and early 30s. According to his curriculum vitae he was “member of the Expert commission of the Eastern Art department at the State Museum Berlin and one of the founders of the Society of the Eastern Art (Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst) Berlin”.42 He was on the board of directors of the Society and acted as treasurer until 1938. Ginsberg also played an active part in the organisation of the large and important exhibition on Chinese Art in Berlin in 1929.

Herbert Ginsberg was born on 27 September 1881 to an industrialist family in Berlin. He studied law and economy in Munich and Berlin, with a dissertation in Heidelberg in 1904. After his education he joined the family banking company and was on the managing board of the family’s cotton mill.

In late 1907 he embarked on a long trip around the world with his brother. They visited Sri Lanka, China and Japan before leaving for America. Precise notes on this trip are preserved in his travel diaries as well as in journals for each country they visited.43

Even before his trip, Herbert Ginsberg had bought a few pieces of Chinese and Japanese art. According to the catalogue of his collection compiled presumably in 1929,44 his first Japanese object, a small wooden sculpture of Bishamon, was given to him by his uncle Max Schlesinger in 1900. The first object he bought was a netsuke acquired from Glenck in Berlin in 1903,45 followed by purchases of a Chinese bronze incense burner at Wagner in Berlin in 190546 and ten netsuke, two woodblock prints and a Japanese lacquer vase at Wagner and Glenck in Berlin and at the auction of the Pettenegg collection in Vienna in 1906 and 1907.47

Yet it must have been on this trip to East Asia that Herbert Ginsberg really started his collection. He bought objects in Beijing and Tianjin and made extensive purchases in Japan. A large number of his netsuke, tsuba and lacquerware was acquired in Japan in 1908.

The catalogue of the collection lists 914 objects of the following categories: 72 bronze figures and vessels from China, Tibet, India, Korea, Japan and Persia, 42 sculptures made of wood, stone or clay, 81 ceramic pieces, 327 Japanese woodblock prints, 22 Japanese and Chinese paintings, 238 netsuke, 11 Japanese masks, 37 pieces of Japanese lacquerware, 35 tsuba and kozuka, 28 textiles from China, Japan and Persia, and 21 carpets.

According to his own account, most objects in Herbert Ginsbergs collection were brought home from his travels in the Far and Near East. In the catalogue of his collection he lists the provenance of most of the objects, except for the main part of the woodblock prints. They demonstrate that most of the objects he bought on his journey were small: netsuke, tsuba, lacquer, textiles and paintings, while he purchased most of his bronzes, sculptures and ceramics after his journey at European art dealers.48

He acquired all of his tsuba through Amiya in Tokyo. Sixty of his netsuke came from Paul Vautier (1865-1938), who had built up a large collection of netsuke, inro and lacquerware between 1890 and 1918 while staying in Tokyo. Six Nō masks came from the collection of the count Meida and a few pieces of lacquerware were bought from Hayashi.

In Europe he frequented quite a number of art dealers, mostly in Berlin. He names Glenck, R. Wagner, Rex & Co., Fricke, Holstein and Pergamenter in Berlin, H. Meyl in Munich, Bluett in London, Demotte in Paris and Vecht in Amsterdam. Some pieces were acquired in Peking through Otto Kümmel in 1927 or Edgar Gutman in 1929. It seems that Ginsberg collected mainly until 1923. Only thirty-eight more pieces were added from 1926 to 1929.

Herbert Ginsberg must have been quite well known known as a collector from early on and was asked to lend his pieces to several exhibitions. Four of his objects went in the exhibition “Ausstellung alter ostasiatischer Kunst” held at the Akademie der Künste in Berlin as early as 1912. For the major 1929 exhibition “Ausstellung chinesischer Kunst” in Berlin, he not only participated as expert and treasurer, but was also one of the main private lenders with twenty-one pieces.

Due to its Jewish origins the family had to flee from Germany in 1938. Herbert Ginsberg and his wife came to Switzerland and continued to Den Haag in Holland. Here, Ginsberg deposited his entire collection as a loan in the Gemeentemuseum. With the German invasion of Holland they retreated to Zeist, where they were able to hide from the Gestapo until the liberation in 1945. Meanwhile the museum had been plundered and destroyed by the Germans. All of his collection was gone. Only a small number of items were later found in the attic of the house of a German SS officer. In 1951 Ginsberg writes: “As a result of World War II the Ostasiatische Kunstabteilung der Berliner Museen as well as the Gesellschaft für Ostasiatische Kunst ceased to exist. But our ‘building’ too is destroyed, since the greater part of our collection has disappeared. Chinese and Japanese paintings, as well as the lacquers, have almost completely vanished. Our Japanese No masks, netzuke and colour prints seem lost for ever.”49

Herbert Ginsberg and his wife emigrated to the United States in 1946 and took up residence in New York, where he died in 1962. Of his large collection only 103 pieces had survived. In 1951 he compiled the catalogue The Remains of our collection with detailed entries and photos of the remaining pieces.

His daughter Marianne Gilbert established contact with the Museum Rietberg in 1971, offering the remains of the collection as a long term loan. According to one of her first letters, she decided to contact the Rietberg Museum, because her “father had known and esteemed Baron Eduard von der Heydt”.50 Eventually, thirty-one pieces – mainly Chinese bronzes and ceramics - were chosen and shipped to Zurich. The loan contract of 1974 determined a loan period of five years with the option of pre-emption by the museum in the event of a sale of the objects. It includes an estimate of the value of the objects by the New York dealer Frank Caro in the amount of 99,100 dollars (at that time corresponding to 329,000 Swiss francs).51

One object was donated by Marianne Gilbert. In 1982 two of the pieces were bought by the Museum Rietberg as a recompense for her costs incurred in crating and shipping her collection. The remaining twenty-eight pieces (Marianne Ginsberg asked that one small bronze sculpture be returned to her) were acquired in 1989 for a reduced price of 200,000 Swiss francs.

Fig. 4: View of part oft he permanent exhibition of Chinese Art at the Museum Rietberg

Photograph: Rainer Wolfsberger, @ Museum Rietberg.

Following its inauguration in 1952, the founding collection of the Museum Rietberg grew through many collectors who had various connections to Eduard von der Heydt and who knew each other through the Berlin network of the golden 1920s. The provenance of pieces in the above-mentioned collections also provides some insights into the Eastern and Western art market. A more profound cross-reference of the collection histories will be a task in the future to gain a better understanding of the art market in the first half of the twentieth century. The focus on provenance shows a reception history which still needs to be written. The Western art market should also be analysed within the context of the art market, with its dealers and intermediaries, archaeologists and travelling art historians, all involved to varying degrees in studying and displacing works from their places of origin. As the Museum Rietberg owns many Chinese art collections such as the ones of J.F.H. Menten, Otto Rücker-Embden, Charles Drenowatz and others, research into their provenance will be an essential requirement for the institution in future (fig. 4).

Alexandra von Przychowski is a curator for Chinese art at the Museum Rietberg.

Esther Tisa Francini is a provenance researcher at the same institution.

1 For the Washington Principles adopted also in Switzerland see https://www.state.gov/p/eur/rt/hlcst/270431.htm and https://www.bak.admin.ch/bak/de/home/kulturerbe/raubkunst/internationale-grundlagen.html, accessed 3 August 2018.

2 Cf. Esther Tisa Francini: Zur Provenienz von vier chinesischen Kunstwerken aus dem Eigentum von Rosa und Jakob Oppenheimer im Museum Rietberg Zürich, in: Kerstin Odendahl and Peter Johannes Weber, eds.: Kulturgüterschutz – Kunstrecht – Kulturrecht. Festschrift für Kurt Siehr zum 75. Geburtstag aus dem Kreise des Doktoranden- und Habilitandenseminars „Kunst und Recht“ (Baden-Baden: Facultas, 2010), 313-329; and From Buddha to Picasso. The collection of Eduard von der Heydt, Museum Rietberg, April 20th until August 18th 2013; Eberhard Illner, ed., Eduard von der Heydt. Kunstsammler Bankier Mäzen (München: Prestel, 2013) with a contribution by Esther Tisa Francini: „Ein Füllhorn künstlerischer Schätze“. Die Sammlung aussereuropäischer Kunst von Eduard von der Heydt, 137-199.

3 www.rietberg.ch/de-ch/sammlung/sammlung-online.aspx, accessed 3 August 2018.

4 For example the relief slab from the gravesite of the Dai family (RCH 102) which before 1911 belonged to the collection of Duan Fang (1861-1911).

5 Christoph Zuschlag, Vom Bild zum Bildnachweis, in Kunstzeitung, no. 263 (July 2018), 3, with many thanks to Nikola Doll for sending me this article.

6 Bénédicte Savoy, Was Museen nicht erzählen, in Le Monde diplomatique, August 2017, 3.

7 See Gail Feigenbaum and Inge Reist, ed., Provenance. An Alternate History of Art (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2012).

8 Bénédicte Savoy, Die Provenienz der Kultur. Von der Trauer des Verlusts zum universalen Menschheitserbe, (Berlin: Matthes und Seitz, 2017).

9 Stacey Pierson, Collectors, Collections and Museums: The Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain, 1560–1960 (Bern: Peter Lang, 2007); Roy Davids and Dominic Jellinek, Provenance: Collectors, Dealers and Scholars in the Field of Chinese Ceramics in Britain and America (Oxford: Roy Davids, 2011); Giuseppe Eskenazi, A dealer’s hand. The Chinese Art World through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, in collaboration with Hajni Elias (London: Scala, 2012); Ting Chang, Travel, Collecting, and Museums of Asian Art in Nineteenth-Century Paris (Farnham: Ashgate 2013); Dorota Chudzicka, “In Love at First Sight Completly, Hopelessly, and Forever with Chinese Art”. The Eugene and Agnes Meyer Collection of Chinese Art at the Freer Gallery of Art, in Collections. A Journal for Museum and Archives Professionals, vol. 10, no. 3 (2014), 331-340, Jason Steuber, ed., Collectors, Collections & Collecting the Arts of China. Histories & Challenges (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2014).

10 https://carp.arts.gla.ac.uk/, accessed 3 August 2018.

11 http://archive.asia.si.edu/collections/provenance-biographies.asp, accessed 3 August 2018.

12 Convenors were Bénédicte Savoy, Charlotte Guichard und Christine Howald, 13-15 October 2016 and for the Workshop Christine Howald and Alexander Hofmann, 13/14 October 2017.

13 https://www.vvak.nl/en/agenda/2018/save-the-date-vvak-lustrum-symposium-asian-art-private-collections-and-their-value-for-public-museums.

14 Many of the paintings are today conserved at the foundation of the Hotel Monte Verità, once in possession of Eduard von der Heydt and in the 1930s an art hotel “avant la lettre”.

15 Roland Jaeger and Gerda Becker-Wirt, eds., Karl With: Lebenserinnerungen eines aussergewöhnlichen Kunstgelehrten (Berlin: Mann, 1997).

16 Patrizia Jirka-Schmitz, Ostasiatika-Händler in Berlin von 1933 bis 1945, in Bianca Welzing-Bräutigam, ed., Spurensuche. Der Berliner Kunsthandel 1933-1945 im Spiegel der Forschung (Berlin: be.bra, 2018), 53-66. See also Jirka-Schmitz’s contribution in this issue of the Journal for Art Market Studies, DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i3.57.

17 For further results on these sales see the article by Ilse von zur Mühlen in this journal, DOI 10.23690/jams.v2i3.75.

18 There are important works on C.T. Loo but more research is needed to better unterstand his sources: Yiyou Wang, ‚The Loouvre from China: A Critical Study of C.T. Loo and the Framing of Chinese Art in the United States, 1915-1950‘ (Ph.D. diss., Ohio University, 2007); Dorota Chudzicka, The Dealer and the Museum: C.T. Loo (1880-1957), the Freer Gallery of Art, and the American Asian Art Market in the 1930s and 1940s, in Eva Blimlinger and Monika Mayer, eds., Kunst sammeln, Kunst handeln. Beiträge des Internationalen Symposiums in Wien (Wien: Böhlau, 2012), 243-254; Géraldine Lenain: Monsieur Loo. Le roman d’un marchand d’art asiatique (Arles: Editions Philippe Picquier, 2013).

19 Asiatische Kunst aus Schweizer Sammlungen, Ausstellung veranstaltet von der Kunsthalle Bern in Verbindung mit der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft der Freunde ostasiatischer Kultur, 1 February to 30 March 1941, Bern 1941; and Asiatische Kunst aus Schweizer Sammlungen, 17 May to 24 August 1941, Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich, Wegleitungen Kunstgewerbemuseum Zürich 150. Because of the big success of the exhibition there was even a third catalogue published, with coloured photographs: Bilderbuch zu bleibender Erinnerung. Otto Fischer and Louis de Hessel were responsible for the content, Johannes Itten for the selection of photographs.

20 “Die Berechtigung einer umfassenden Ausstellung asiatischer Kunst in der Schweiz braucht nicht begründet zu werden. Zahlreiche Sammler haben die Kunst des Fernen Ostens seit vielen Jahren zum Gegenstand ihres Interesses gemacht. Verständnis und Anteilnahme dafür mögen geweckt worden sein durch die Beziehungen wirtschaftlicher Art, die Handel und Industrie mit jenem Kontinent herstellten, und die zugleich auch den direkten Erwerb wertvoller Stücke ermöglichten”. E.H.v. Tscharner und Max Huggler, preface, in Asiatische Kunst, Kunsthalle Bern 1941, 3.

21 Museum Rietberg Archive, p. 0005-0013, Sammlung Mary Mantel-Hess.

22 H.F.E. Visser, Frühe chinesische Kunst in der Sammlung Hasler, Winterthur, in: Asiatische Studien 1957/58, 11, no. 3-4, 113-118 with many photographs.

23 On Dirksen as a collector see Carolin Reimers: Dr. Herbert Dirksen. Ein deutscher Botschafter als Sammler ostasiatischer Kunst, in: Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, no. 1 (2001), 22-32.

24 Ibid., 24.

25 Herbert von Dirksen, Briefe aus Japan 1933-1938, printed as a manuscript in 1938.

26 For a critical contextualisation see Frauke Kempka, Kunstgenuss im Dienste der Propaganda. Die „Ausstellung altjapanischer Kunst“ in Berlin 1939, in Ostasiatische Zeitschrift, Neue Folge, no. 8 (2004), 22-32.

27 Ibid., 11.

28 Extensive correspondence is preserved in the Federal Archive in Berlin (BArch Berlin, Bestand 2049, Nachlass Herbert von Dirksen).

29 Eduard von der Heydt „Zur Erinnerung an Herbert Dirksen“, in Schweizer Monatshefte: Zeitschrift für Politik, Wirtschaft, Kultur, vol. 35 (1955-1956), no. 11. Translation by the authors.

30 On the life of Otto Fischer see: Nikolaus Meier, Ars una: Der Kunsthistoriker Otto Fischer (1886–1948) in Reutlinger Geschichtsblätter no. 50 (2011), 195; Stadt Reutlingen, Otto Fischer: Ein Kunsthistoriker des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts, special edition from Reutlinger Geschichtsblätter no. 2 (1986).

31 Otto Fischer, China und Deutschland. Ein Versuch, in Georg Schreiber, ed., Deutschtum und Ausland. Studien zum Auslanddeutschtum und zur Auslandskultur, vol. 12 (Münster 1927).

32 Otto Fischer, Wanderfahrten eines Kunstfreundes in China und Japan (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1939).

33 The popular prints of his collection are subject of a master thesis by Alina Martimyanova, The Language of Chinese Folk Art: A Survey of Otto Fischers’s Collection of Chinese Popular Prints and Their Color Characteristics, Master’s Thesis, University of Zürich, Institute of Art History, 2015.

34 Fischer, Wanderfahrten eines Kunstfreundes, 410.

35 Ibid., 454. In Jinan he purchased sets of rubbings of Xiaotangshan and Wuliangzi.

36 Ibid., 431.

37 Johannes Itten, Chinesische Steinabklatsche (Zürich: Kunstgewerbemuseum, 1944).

38 Meier, 195.

39 Published in Otto Fischer, Chinesische Plastik, München 1948, plate 126

40 Meier, 192.

41 Documents on Herbert Ginsberg’s life and collection are preserved at the Leo Baeck Institute in New York, including his curriculum vitae written by himself and by his daughter Marianne Gilbert, his diaries from his journeys to Asia and the catalogues of his collection. Guide to the Gilbert Family Collection (herafter GFC): http://findingaids.cjh.org/?pID=431113.

42 GFC Box 2/8: http://www.archive.org/stream/gilbertfamily01reel02#page/n50/mode/1up.

43 GFC Box 3: Journals of his Journeys to China, India and Sri Lanka, Japan, Russia and Silili; Box 5/6 Ginsberg’s diary from China in printed form; Box 6 and 7: travel diaries.

44 The catalogue preserved in the Leo Beck institute has no date. From the dates of his purchases it seems, that it was first compiled shortly after 1923 with his purchases between 1903 and 1923, and that some pages and numbers were added later, all of them purchases of 1926 to 1929.

45 GFC Box 7/4/ 864, p. 39, no. 112.

46 GFC Box 7/4/702, p. 18, no. 14.

47 http://www.archive.org/stream/gilbertfamily01reel07#page/n901/mode/1up/search/1906.

http://www.archive.org/stream/gilbertfamily01reel07#page/n901/mode/1up/search/1907.

48 According to his catalogue the following number of items was bought on his journey: bronzes 19 out of 72, sculpture 7 out of 45, ceramics 21 out of 81, painting 15 out of 22, netsuke 196 out of 238 (21 without provenance), masks 9 out of 11, lacquerware 32 out of 37, tsuba and textiles all, woodblock prints 37.

49 Herbert Ginsberg, The Remains of our collection, privately published in New York, 1951; Archive Museum Rietberg, preface.

50 Letter from Marianne Gilbert to Eberhard Fischer, 3 July 1972, Archive Museum Rietberg.

51 All documents in the Archive Museum Rietberg.