ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Ronit Milano

Recent analyses of the art world show that the market has taken a primary position in generating the narratives of the art discourse which was led in the past by museums and curators. This shift raises a significant political issue: while conventional curatorial practices are subjective and elitist, we might assume that a shift towards the primacy of more organic structures, such as the market, conveys a more equal representation of the participants in the art world, and thus a more ethical structure of it. Yet ethics is a concept that is more social than economic, and the above assumption therefore depends on the prevailing economic approach at a particular time and place, and the political and cultural agenda it serves. This paper aims to offer a qualitative analysis of the contemporary art market as shaped by the neoliberal conditions underlying it, through the perspective of moral economy. Specifically, this study will evaluate the concept of equality in relation to online auctions, positioning the latter at the crossroads of political and social theory.

This essay focuses on art auctions on the floor and on the internet in order to discuss moral issues in the current operation of the art world. In doing so, it aims to offer a better understanding of the free art market and of its relation to moral economics. My discussion will unfold along three intersecting trajectories that explore the economic, social and political dimensions of this market while focusing on both ethics and scale. While attending to the sub-market of art auctions, I will also attempt to draw some general implications concerning both the operation of the art market and the relations between physical auctions and online auctions. Although the limited scope of the discussion has led me to concentrate on auction houses while excluding galleries and private sales, it is important to acknowledge the increasingly blurred lines between auctions and private sales, as the two biggest auction houses – Christie’s and Sotheby’s – have recently entered the latter sector.

Throughout this paper, I will engage with the terms “art world” and “art market”. The term “art world” will relate to the wide political construct that includes all the players in the art field (museums, curators, private foundations, collectors, sellers, artists, etc.), while “art market” will represent the economic dimension of the art world, which is, roughly speaking, comprised of sellers and buyers (also referred to below as clients and consumers). In the first part of my analysis, I will offer a model for understanding the art market in political and social terms, rather than only in economic terms, as most scholarship does; the second part of my analysis will apply this model to the online sector by studying the case of Artsy, the leading internet-based auction house that offers its services exclusively online. I will conclude by predicting that in the future, the online sector will come to constitute a site of political and ethical change in the art market.

In an attempt to point to practices or institutions that can ultimately reshape the economic, social and political structure of the art market, I will first draw an analogy between the Western market as a whole and the contemporary art market. A simplified definition of the neoliberal economy, which characterizes the current West, would describe it as synonymous with the concept of a free market that encourages competition and minimizes regulation. The art world – as Pamela Lee argued in her book Forgetting the Art World – forms an integral part of the real world.1 This understanding invokes Pierre Bourdieu’s ideas on taste, capital and social class – developed from 1979 and well into the 1990s – which described the field of cultural production as contingent with social and economic parameters.2 It was not a coincidence that Bourdieu’s perception of the field as inextricably tied to the concept of capital (as it is constructed in a particular moment), emerged in parallel to the rise of a free economy throughout the West. What would come to be known as “Neoliberalism” was in Bourdieuan terms a platform that enabled a free movement and transformation of capital between the financial and the cultural realms. What is even more striking, is that Bourdieu predicted that the amplification of a free movement of capital would entail a social change, led primarily by a rise in inequality. Building on Lee and Bourdieu I suggest that since the economy of the art world complies with the economic codes of the real world, what we are in fact witnessing in the art field is a sub-market that operates under extreme neoliberal conditions – that is, without any political body regulating its economy. In the context of the art market, no mechanism is in place to protect participants in the market, or to restrict or diminish the natural results of a free market, such as unequal distribution of capital, a shrinking of the middle class, and the empowerment of corporations.

Yet can these terms – capital, inequality, classes – even be validly employed in a discussion of the art market? Can we, in this context, still refer to “socioeconomic classes” or to the distribution of capital between classes and individuals? Can we identify a form of corporate culture within the contemporary art market? How can we describe regulation or a lack of it in the art market? And how shall we define the difference between “public” and “private”? These questions are crucial to considering the moral and ethical economics of the art market, and thus add another layer to Lee and Bourdieu’s approaches. The following analysis will define the “society” of the art market as comprised of consumers/buyers with greater or fewer resources; public institutions such as museums, which admittedly have lost their prominent position to the private sector; and private institutions, which I will show to be complex and opaque structures that rely on the connections between powerful sellers/firms, top-capital holders and leading cultural figures (celebrities such as artists, museum functionaries, or mega-collectors). The art market, therefore, is a construct that integrates political, social, economic, and ethical dimensions. It is predicated upon a game of power between players that is supposedly regulated and restricted by political bodies which were nominated by the players in a more or less democratic way. In what follows, I will thus theorize the participants of the art world as a ”society”, while frequently using the term “class” to refer to the various financial categories of buyers. I will refer to top-tier buyers as the “high-class society members,” and to the lower-end buyers (associated with the market for mid- to low-value art) as the “lower classes,” “masses,” or “low-class buyers.”

The market of art auctions is dominated by two major players – Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Indeed, it is impossible to analyze the art auction market without relating to this royal duo. According to the latest Art Basel report, in 2018 the entire art market reached a value of $67.4 billion, of which 46% came from the auction sector.3 Together, Christie’s and Sotheby’s hold 40% of the auction market. In fact, the 2019 Art Basel report states that “The top five auction houses (Christie’s, Sotheby’s, Poly Auction, China Guardian, and Phillips) accounted for over half of the value of global market sales.”4 In classical economics, the term “oligopoly”– a relative of the better-known term “monopoly”– refers to a market that is dominated by a small number of large sellers. Yet considering that Poly Auction and China Guardian focus mostly on decorative arts and antiques, and Phillips is very much in third place with regard to sales of twentieth-century and contemporary art, the contemporary fine art market is clearly led by the powerful duo Christie’s and Sotheby’s – to whom we might refer as a duopoly.5 This situation does not mean that there is no competition on the market, which also includes around five hundred second-tier auction houses, as well as many other smaller, domestic auctions houses in the third tier. Nevertheless, it is marked by two significant characteristics that economists recognize as the results of concentration in any market: high barriers constricting the entry of other sellers into the market and the uninterrupted ability of the dominant players – Christie’s and Sotheby’s – to affect prices.6

The first point is a complicated one. How can we talk about high barriers in a free market that is open to competition and is not governed by regulations? The answer to this question ties the results of neoliberalism to moral economics: market concentration – which is an inevitable outcome of a non-regulated free economy – might be legal, yet is hardly ethical in terms of social politics. Money and power forge a circle that amplifies itself; as a private firm becomes bigger and stronger it devours its competitors many times by buying them, and strengthens its power by merging with other firms. Mergers and acquisitions are commonly done to expand a company’s reach into new segments or to gain market shares – a mode of operation known as “corporate culture”, which has been so famously criticized by Naomi Klein and many others.7 In corporate culture, power is obtained by size and reputation (symbolic value); translating Bourdieu’s language into the language of capitalism, we could refer to this symbolic value by the term “brand”.8 As the two largest auction houses in the world, Christie’s and Sotheby’s are powerful not only in terms of their financial value and abilities, but also in terms of their brand value. A customer is more likely to trust a credible, established firm with a high reputation than a small, new company that has just entered the field. This is even truer in the case of top-tier buyers, who make large expenditures and prefer to go along with a big, well-established name. New and smaller sellers are thus restricted – not legally but effectively – to relatively small-scale deals, which further enhance the dominance of the large firms. Moreover, as the field expands, large firms are usually strong and wealthy enough to expand along with the market through investments. For instance, in the absence of regulation, big companies can not only affect market competition by acquiring rising competitors; they can also purchase technology companies, and thus speed up development instead of developing in-house, from scratch – as was the case when Christie’s bought Collectrium in 2015 (in this case, a failed investment, which nevertheless demonstrates the firm’s business agenda and its financial abilities) or when it engaged with the blockchain title registry Artory last year, or when Sotheby’s acquired Thread Genius, also in 2018. This pattern was also evident when Christie’s and Sotheby’s had to respond to the online sub-market, which entered the game in the beginning of the twenty-first century – a case to which I shall return in the last part of this article.

As I would like to suggest, Christie’s and Sotheby’s operations can therefore be analyzed as part of the discourse on corporate culture and neoliberalism. Still, one might insist on asking why the empowerment of Christie’s and Sotheby’s by the natural market forces is in fact problematic, and whether moral or ethical issues are even relevant in a market that is run legally and under consent. Milton Friedman, the American father of neoliberalism, claimed that “a free private market involves the absence of a coercion. People deal with one another voluntarily, not because somebody tells them to, or forces them to. . . . So the essence of a free private market is that it is a situation in which everybody deals with one another because he or she believes he or she will be better off.”9 Friedman is, of course, right. When a billionaire chooses to spend millions at a Christie’s auction rather than in a smaller auction venue, she does so because she believes she is better off making this choice. Yet is this necessarily the case? While Christie’s and Sotheby’s might not be able to arbitrarily set prices, what they can do, for instance, because they have financial strength, is to avoid sales that will “damage” their market for various reasons (not to mention the illegal possibility of price-fixing on commissions, as Christie’s and Sotheby’s did in the 1990s).10 In other words, the cartel-like structure and the financial leverage these two institutions have over their competitors can indirectly affect market prices – which is the second result of concentration. For this reason, a state of oligopoly, duopoly or a monopoly can be viewed as socially immoral, or at least unethical: information is not transparent, not all the players hold equal access to it, and the power is concentrated in a way that strengthens certain players and consequently weakens others. Importantly, although most progressive societies mistakenly equate morality with legality, it is obvious that such a situation raises an ethical debate, touching upon issues of domination, freedom, and the proper exercise of power. Christie’s and Sotheby’s, however, are two businesses seeking to maximize profit and are not restricted or ethically guided by any political bodies.11 Additionally, whereas top-tier clients are powerful enough to negotiate and financially balance the two companies, the majority of the clients are not united into a collective force – an empowering practice that Marx and other opponents of capitalism saw as crucial to an ethical critique of the economy and of society.

In fact, top-tier auction houses have an unofficial alliance with top-tier collectors/buyers. Together, they generate a sort of sub-market, in which everything is “big”: big money, big power, and big names, or brands. Like any market, this sub-market of “bigness” operates on the basis of practices and institutions. As theorist Alasdair MacIntyre explains:

Practices must not be confused with institutions. Chess, physics and medicine are practices; chess clubs, laboratories, universities and hospitals are institutions. Institutions are characteristically and necessarily concerned with what I have called external goods. They are involved in acquiring money and other material goods; they are structured in terms of power and status, and they distribute money, power and status as rewards.12

In applying MacIntyre’s theory to the top-tier art market, we can perceive art commerce as a practice, and Christie’s and Sotheby’s as institutions. Yet I would like to suggest that according to this definition, we can also visualize top-tier clients as one-man institutions, because they, like brands, are related not only to the circulation of money but also to that of power and status – which, in this case, is affiliated with the auction houses. As clients of Christie’s and Sotheby’s, they maximize their reward as individuals and as one-man institutions by acquiring both luxury goods and, even more so, social status. However, as we zoom-out to the economy of the entire art auction market, what we find is a very narrow top-tier in which most of the money, power and status are concentrated. This is the market of “bigness” to which I referred earlier. It is also the reason I perceive the top-tier auction-houses, galleries and collectors as a unified political and economic construct that shapes the entire market.

Considering this concentration, we may ask how the top-tier, which behaves as an oligopoly and reaches equilibrium within its own sub-market, engages with second- and third-tier institutions and individuals, if at all. In other words, what is the structure and rationale of the art-world economy as a whole, and to what extent is it predicated upon ethical politics? This question leads to the social dimension of the art market – that is, to the concept of classes. We can use two main structural models to define classes within the art world: driven by quantitative analysis, the first possible model consists of the conventional division of the art market into three financial tiers – a model especially suitable to the arena of auction houses.13 Alternatively, we could adopt the more general division of the art market into high and middle-low, which is used by many scholars and critics today. Either way, the top or high-end market represents the institutionalized market of “bigness,” whereas the structure of the rest of the market – to which I now wish to turn – remains ambiguous. I shall therefore begin with two facts: first, in 2018, the number of millionaires worldwide continued to increase, reaching a historical high of 42.2 million people; second, in 2018 the top 10% of wealth holders owned 85% of the world’s wealth, and the top percentile alone accounts for almost half of all household wealth (47%).14 These numbers do not relate specifically to the art sector, but rather to society as a whole, indicating a growing inequality in the division of capital. What we are witnessing, as a result of neoliberal economic policies, is a disproportionate growth in the amount of capital possessed by the upper class; a large expansion of the low class; and, most significantly, a radical shrinking of the middle class. Can we find a parallel to these facts in the art sector? A survey conducted last year (2018) in the United States for the Art Basel report revealed that almost 80% of the individuals active in the art market bought works for less than $5,000, while less than 1% bought at prices in excess of $1 million.15 Since this survey does not provide a breakdown within each financial class, it would be inaccurate (although not irrational) to deduce that 80% of the art buyers belong to the lower economic class, but this number does indicate the existence of a significant amount of products in a price range accessible to, and more identified with, the lower classes among art-world consumers.

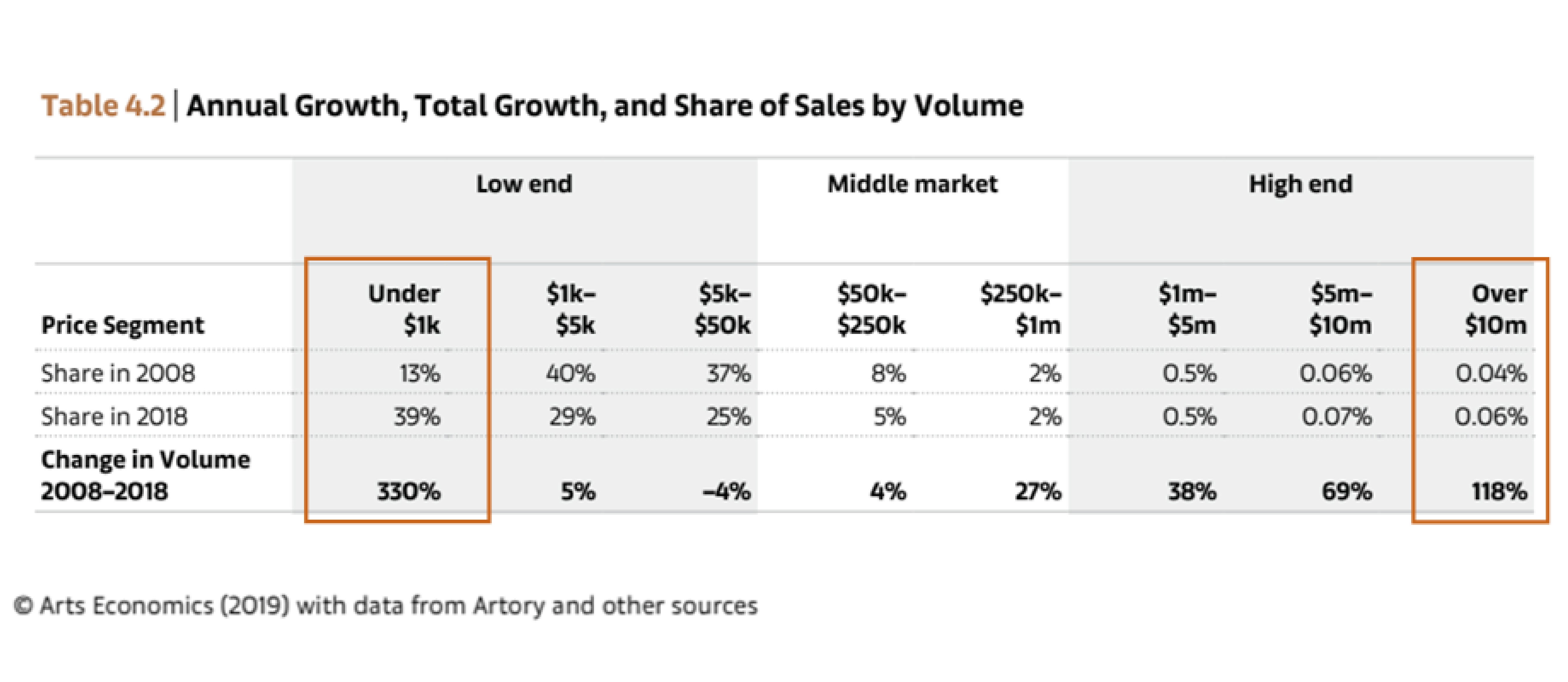

If we assume that changes in the volume of low-end sales imply changes in the activity of less affluent buyers, it is worth scrutinizing the changes in the last decade (Table 1). The 2019 Art Basel report reveals that between 2008 and 2018, the major changes in the auction sector, in terms of volume, occurred at both ends of the market, while the share of the middle market remained relatively steady. Specifically, the share of segments priced over $10 million grew in the past ten years; nevertheless, in terms of market percentages, we are talking about a marginal rise from 0.04% to 0.06%. More telling, in terms of social economics, is the shift within the low end of the market, that is, works priced up to $50,000, which in 2018 occupied 93% of the market: within this range, the share of works priced under $1,000 tripled, rising from 13% in 2008 to 39% in 2018. This was mainly at the expense of works priced between $1,000-$50,000. If we look at the art market from a social perspective, we may be able to understand this shift as a change in the division of classes within the market – that is, a small growth of the highest class, and a major expansion of the lowest class, at the expense of the middle classes (specifically, the middle-low classes). This, of course, throws us back to the structural and social results of neoliberal economies, which entail the shrinking of the middle classes and the acceleration of poverty, parallel to the strengthening of a small but powerful upper class.

Table 1: Quoted from Dr. Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, available online https://www.artbasel.com/news/art-market-report, 161.

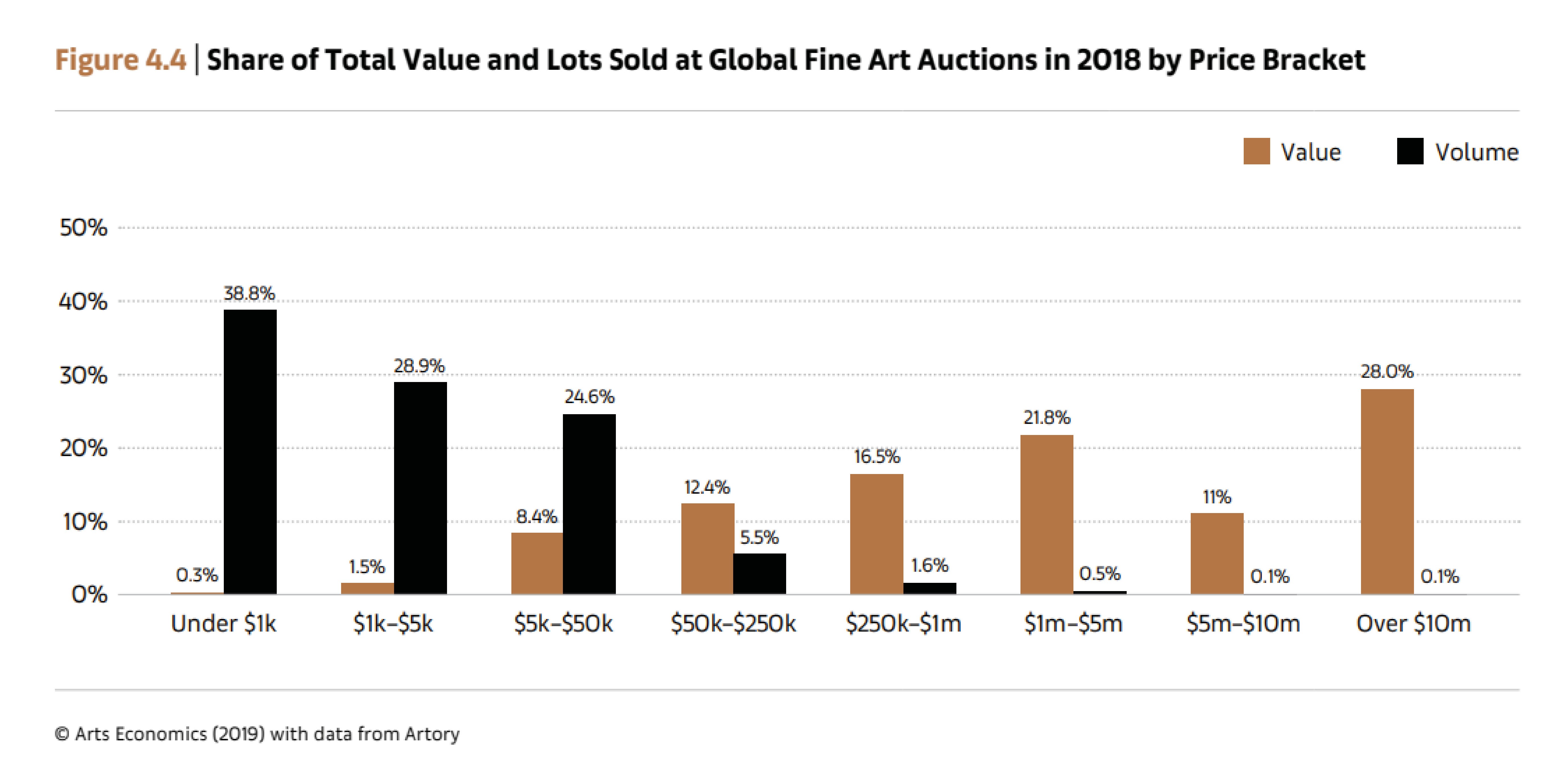

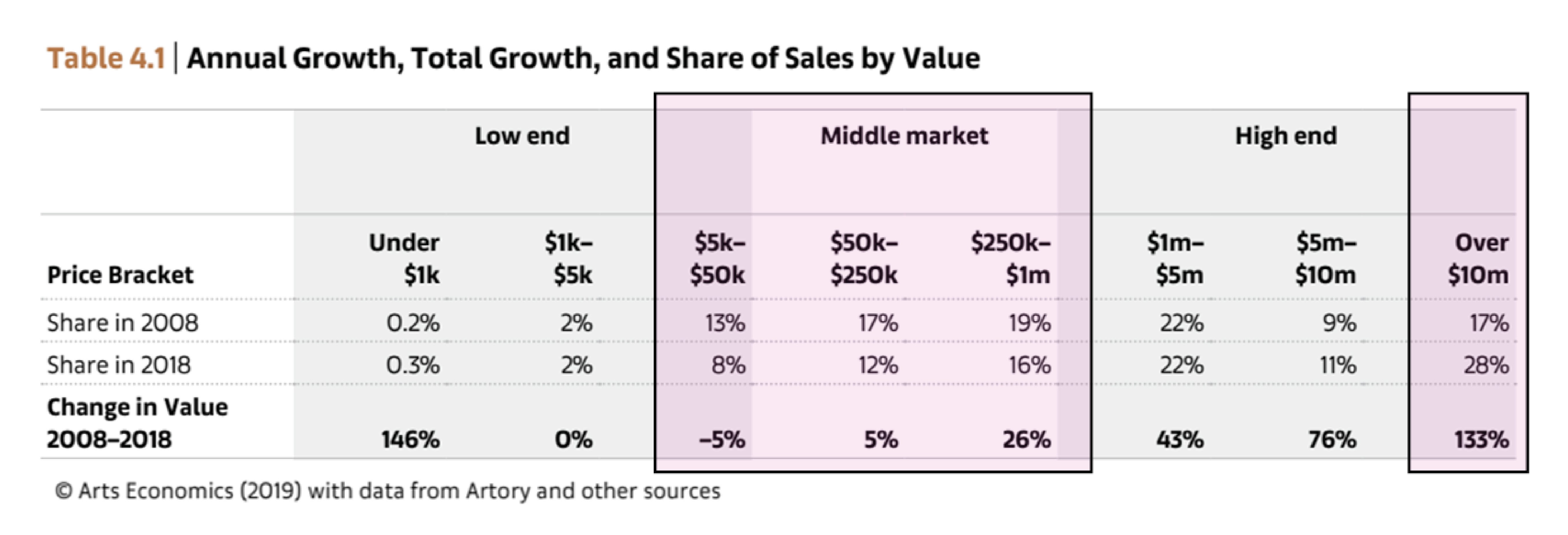

It is important to emphasize that the growth at the low end of the auction market is indicated here as related to volume (quantity), rather than to the value (capital) it holds or represents. While segments priced under $1,000 comprised 39% of the market in 2018, their total share of value amounted to 0.3% of the market (Table 2). At the other end of the chart, the total value of works priced over $10 million, which represents 0.1% of the market by volume, reflects 28% of the market by value. As this data reveals, a tiny upper class, which can be identified with 0.1% of sold works, is in possession of more than a quarter of the market’s capital, while a huge lower class, which can be identified with more than a third of the sales on the market, is in possession of 0.3% of the market’s capital.16 Taken together, the low end of the market (with segments up to $50,000) can be associated with more than 90% of the clients on the market, while reflecting less than 10% of the market’s value. In comparison to previous years, we are witnessing a growing state of inequality in the distribution of capital. Supporting this assertion is the chart dividing the market by value, which surveys the change over the last decade (Table 3): we can see that despite the major increase in the volume of artworks sold for less than $1,000, their total value increased between 2008 and 2018 by only 0.1%. This is an insignificant increase compared to the rise from 17% to 28% of the market’s share by value, which concentrates in the highest category. This rise comes from the middle-market categories ($5K-1M), whose share shrunk from 49% in 2008 to 36% in 2018. Simply put, while the middle class was shrinking and the low class was growing, capital shifted from the shrinking middle class to the upper class. This situation is not surprising, considering that the art market operates in accordance with neoliberal codes and conditions.

Table 2: Quoted from Dr. Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 182.

Table 3: Quoted from Dr Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 159.

Having roughly delineated the socioeconomic structure of the art auction market, it is important to bear in mind that questions involving social ethics arise not so much from existing financial conditions, but rather from political conditions. Yet politics and money, as is well known, are inextricably tied – a fact that requires us to acknowledge the political power of the upper class in shaping and managing the art market, and by extension the art world. In his “Plea for Responsible Art,” published in 2018 in the second volume of Art and the Challenge of Markets, the sociologist Antoine Hennion astutely analyzes a photograph of Jeff Koons and Jean-Jacques Aillagon, president of the domain of Versailles.17 Regarding the much-discussed ties between Aillagon and the billionaire Francois Pinault – the owner of Christie’s and an avid collector of Koons – Hennion says: “Art circles, corridors of power, trading floors and cultural fairs, wealthy clubs, and commercial networks, nothing was missing from the picture. . . . [The art world] benefits from all the glory, general recognition, cultural prestige and public success, and unflinching support of the narrow yet solidary worlds of money and power, critics and institutions.”18 It is precisely this institutionalization of money and power in the art world that seems to undermine ethical principles, such as the separation of public and private interests and capital, or the equal distribution of capital. In the past we were encouraged to think that public art institutions imbued the art world with societal values; today, however, the (private) art market, which assumes more and more political power, has become increasingly involved in shaping aesthetic values. In doing so, it is replacing the former gatekeepers – curators and museums – which are increasingly dependent on private funding. This reality further underscores my above definition of private mega-collectors and famous superstar-artists as one-man-institutions – brands that hold enough political power to shape the practical codes of the art world. Smaller political entities in this arena, including emerging artists, experimental and more critical art initiatives, and lower-class art lovers, remain, at best, on the margins of the market; due to the insignificant monetary power they represent, they hold zero power to affect the art world.

As for the political position of auction houses (as well as galleries and dealers), the picture is multifaceted: as John Zarobell admits in Art and the Global Economy (2017), “it is not only Christie’s and Sotheby’s that have prospered as a result of increased global investment in art but a wide variety of auction houses around the world.”19 This statement perfectly captures the neoliberal maxim: the strengthening of the upper class will lead to new private investments, which will in turn strengthen the entire private sector and enable new entrepreneurs to join the game. This process, however, occurs only in theory; as demonstrated above, in reality, despite the absence of complicated regulations that could prevent the opening of new sales venues, the natural barriers have become increasingly difficult to overcome. According to a survey conducted by the latest Art Basel report, “the general trend for gallery openings has been a steady decline. ... [T]he number of new galleries established in 2018 was 86% less than in 2008..”20 In a parallel survey conducted last year, dealers declared the most significant barriers to be the following: a growing difficulty in finding new buyers, and the rising costs of participation in large art fairs.21 These statements point to the growing closure of the “market of bigness” – a game which everyone is free to enter in principle, but not in practice. Although the art world and the art market have expanded geographically, the “market of bigness” owes more to the implementation of corporate culture and to a reality in which a large number of salesrooms belong to a small number of companies, rather than to a real increase in the number of players as a result of a free and competitive market. Thus, whether we focus on auction houses or on the wider array of sellers on the market, we cannot ignore the political power of the top-tier players.

Yet minority rule has always characterized the art world. Prior to neoliberalism and to the rule of the financial elite, curators and museums dictated the agenda of the art market. The shift of power from public curators and museums to holders of private capital in the twenty-first century is the result of a liberal economy and ideology overtaking a free art market. Yet despite the subjective essence of curatorial practices in public institutions, such practices were still predicated upon the freedom to promote various types of artists and art. In that sense, the rule of the curators allowed for a potentially more pluralistic art world. Moreover, although most of the art displayed in such institutions remained financially inaccessible to middle- and lower-class art lovers, its presentation still generated a richer picture of the art world, whose highest values were aesthetic values. It is thus safe to state that, while equality and an equal distribution of power were never strong characteristics of the art world, they have been further undermined by the shift of power from the public to the private sector.

The growing inequality and increased concentration of capital described above in an art-world context reflect larger social and economic changes brought about during the first two decades of the twenty-first century, alongside the return of identity politics and an empowerment of right-wing parties. Taken together, these developments are also significant signs of the weakening of democracy. Yet alongside neoliberalism and its crucial consequences, the twenty-first century also ushered in the internet, whose free access to information and collapsing geographical boundaries held a huge promise for democratization and equality. Since this discussion cannot address all of the ways in which the internet has affected the art world, or even the art market, in the following passages I will focus on the example of online art auctions. Another important concept central to the construction of “bigness” and related to the capitalist idea of branding – especially in the context of the internet – is that of celebrity culture. When Isabelle Graw’s High Price was published in 2009, it was perhaps too early to discuss the implications of the internet for the art market, yet Graw did draw a connection between the art market, commodities and brands.22 She located the art world between the market and celebrity culture, explicitly acknowledging the art world’s submission to neoliberal economic conditions and defining it as intertwined with the unprecedented cultural reign of stars. Indeed, we encounter celebrity culture within the contemporary art world in almost every function: in previous studies, I have discussed the role of superstar-artists and of the mega-collector as brand names operating on the market;23 to these “supersize” titles we can add the star-curator, who today would be most closely identified with the private sector of biennials and art fairs, as well as the blockbuster exhibition – a typically monographic exhibition which, as I have shown elsewhere, similarly centers on a brand name.24 To this category of “bigness” we can of course add the blue-chip artwork (which, as Olav Velthuis shows, is usually also big in size).25 The Koons-Aillagon-Pinault triumvirate referred to by Hennion epitomizes the celebrity culture conceptualized by Graw, and translates it into political power. Today’s art world, and by extension the art market, is ruled by celebrities. The artworks are simply the commodities through which the brand-names – of people, firms or institutions – are created and promoted.

The internet, whose prevalence advanced parallel to the growing intertwinement of the art world with celebrity culture, proved to be an important tool in the promotion and distribution of trends, brand-names, and, generally speaking, of “bigness”. This platform is socially-inclined, not only thanks to its openness and accessibility, but also thanks to the extent that it presents almost no barriers for the entrance of ideas and content. Yet as in the case of museum curators, who were subject to a confusion between the terms “public” and “societal”, the internet carries a public appeal, while in fact promoting what are, for the most part, hegemonic and popular ideologies. Searching online, one can easily recognize the current ideal of “bigness”, which is transmitted through a critical mass of materials related to brands and to celebrity culture.

This understanding is particularly important when the internet and commerce intersect. Commerce and brands have, of course, been interconnected since early modernity; yet the mass accessibility of the internet dictates a new politics within the art market – a political behavior that acknowledges the lower classes active on the market and that provides them with a sense of participation in the game. It is precisely this illusion, cultivated under the sign of neoliberalism, which keeps the masses silent and provides political stability.26 As the contemporary art world is increasingly marked by what curator Paco Barragán called the “Grand Tour of the 21st Century,”27 professionals and millionaires tour the biennials and art fairs, while the masses tour the internet, which has come to dominate the world of mass media. Online information is accessible to all, yet is filtered and shaped by market forces – the big artists, the big collectors and the big dealers. For the lower-class client, the grand tour is a virtual reality informed by real trends and big names. The next stop necessary in order to turn this virtual reality into a physical reality, which is only one click away, is the online store, which facilitates the acquisition of real commodities created by both bigger and lesser names. In this context, what enables true participation is not the internet as a platform offering content, but rather the store. Yet it is the internet that makes the store and the commodities immediately accessible, and is therefore essential for enabling everyone to purchase artworks. Within the art world, e-commerce is thus crucial for imbuing the masses with an illusion of political participation and effective power – an illusion that entails both a false experience of equality and a sustainable political system.

General online commerce constitutes 12% of the overall market, and demonstrates a growth of 25% year-on-year. By comparison, the entrance of online commerce to the art market has been slower: In 2018, the art market was worth $67.4 billion and e-commerce generated $6 billion, accounting for 9% of the market, up 11% year-on-year.28 The online art market, which became significant at the turn of the millennium with technology companies that sought to bring art to the masses, is not an easy market for art. Some scholars express a skeptical position, pointing to a problem of credibility with regard to online platforms and questioning the profitability of such companies. Indeed, most of these start-up companies are not profitable. Even the leading online company, Artsy, which operates exclusively on the internet, refuses to expose its profits. Christie’s, which entered the online arena unwillingly in order to maintain its prominent position, has admitted that the online business still loses money, although sales value continues to rise, reaching $86.4 million in 2018, in comparison to less than $5 million in 2012.29 It is important to remember, however, that unprofitability in the early stages of development is true of all start-up companies in all fields. Such companies aim at building a successful – and eventually profitable – product, and the money they obtain goes to research and development. However, they will not be able to obtain investments if they do not convince the investors that their product carries financial potential. They would have to convince them that the market is growing, and to show how their product will develop and eventually become profitable. Investors, in turn, once they decide to put their money into a certain company and affiliate themselves with it, express their faith in the product and in the market’s development in a certain direction.

Artsy, the most prominent player in the online arena of fine-art sales, was founded as a technology-based start-up by Carter Cleveland, who graduated from Princeton with a major in computer science, and Sebastian Cwilich, a former executive at Christie’s. The company’s investors and board members include leading names from the field of technology, such as Eric Schmidt, formerly an executive chairman of Google, Jack Dorsey, the co-founder of Twitter, and Rich Barton, the founder of Expedia; additional investors include several established venture capital firms, as well as prominent art world figures such as the gallerists Larry Gagosian and David Zwirner, the businesswoman and art collector Dasha Zhukova, and Marc Glimcher, the president of Pace Gallery. In 2017, Artsy completed a seventh round of fundraising of over $50 million.30 Although this example does not necessarily point to the success of the online market, it does point to a certain “vibe” – that is, to a professional, educated assumption of where the market is headed. As the 2019 Art Basel report states, “Most of the auction houses surveyed were optimistic that their online sales would increase in the near future: 85% thought they would increase over the next five years (versus only 62% in 2017).”31 Whereas the Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2019 ranks Artsy in third place, following Sotheby’s and Christie’s, Artsy is the first in this list among online-only companies.32 In a survey conducted by Hiscox for its 2018 report, Artsy was nominated most often by its peer-companies as a current marketleader.33 The company does not release revenue data, but we learn that in 2018 it hosted over 400 auctions (live partnered auctions and online-only sales), more than double the 190 auctions hosted in 2017.34 The data delivered by Artsy also reveal that “the price ceiling of works sold via the platform also increased in 2018, with the highest winning bid being $590,000, for George Condo’s Marc Jacobs in a sale with Phillips. In the gallery sector, a record was also set on the platform, with a European buyer reportedly paying $2 million for a work, sight unseen. The company had more than 1.3 million registered users in 2018, up 40% on 2017, and experienced a 58% increase in sales volumes.”35 How can it be, then, that the sector is not yet profitable? And what are the potential gains from such a non-profitable business?

We already know that digital platforms and e-commerce have seriously affected many sectors, including the markets for books and music. It is widely accepted that the art market has been affected to a lesser extent because of the tangible qualities of the products and the demand for high quality; yet another significant reason is the financial structure of the market detailed in the preceding passages. Unlike most commercial sectors, the art market does not rely on volume, but rather on value. To paraphrase the above findings, within the auctions sector more boldly, artworks sold for over $10 million, while constituting less than 1% of the market in volume, reflect almost two thirds of the market in value. The activity of established, heavy buyers still revolves mainly around offline top-tier auction houses and galleries, rather than online. Artsy might attract 2.5 million visitors every month, as it reports, but the works sold online belong mostly to the lower categories – commanding prices of up to $50,000.36

Unlike Artsy, Christie’s and Sotheby’s income relies mostly on sales made on the floor, where most of the blue-chip works are sold. Moreover, only members of the upper class can afford to participate physically in auctions and to see the works in reality. It would not be unreasonable to assume that the majority of art buyers on online platforms do not belong to the privileged upper class. For them, platforms such as Artsy offer a chance of belonging, of participating on the market, and of experiencing a political sense of worthiness. If we speculate that the lower economic classes are the majority of the clientele of Artsy, for example, the inevitable conclusion would be that although online sales are increasing, their value will remain low in respect to the overall market.

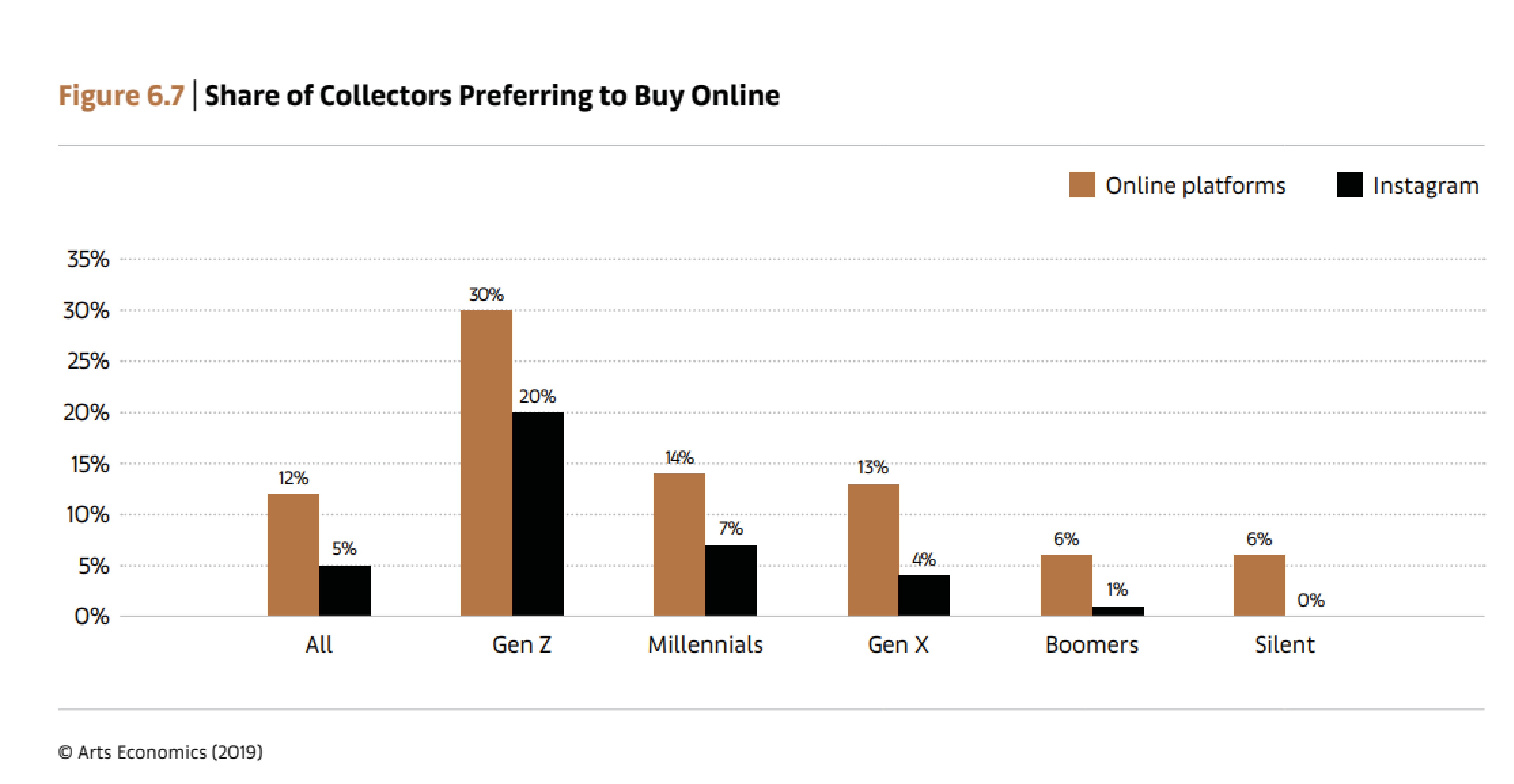

While I have thus far conceptualized the idea of class in an art-market context, I now wish to turn to the factor of age and ultimately to tie the two together. Despite the absence of sufficient data, we may generally assume that mega-collectors belong to the older generations of society, and that their engagement with the internet is likely to be lesser than that of millennials. Generational differences are important for my discussion: while 84% of baby-boomers prefer to shop in-store, millennials (Generation Y), who are responsible for over 50% of all shopping online, are used to instant accessibility and instant action. Unlike Boomers and Generation X, they do not spend much time on research, and rely mostly on peer ratings. As Table 4 demonstrates, art collectors follow those tendencies, as a “considerably higher share of younger collectors preferred online channels for sourcing and purchasing art than older generations. For the youngest Gen Z collectors, the share favoring online channels was more than twice the average, at 30%, for online platforms, and 20% for sales facilitated through Instagram. Similarly, the share of millennials and Gen X was more than twice that of the two older generations, reinforcing again that preferences for buying online tended to be inversely proportional to age.”37 It is understood that the millennials, and subsequently the Zs, will dictate the shape of the online market in the future, but can we imagine how the art market will look as a result?

Table 4: Quoted from Dr. Clare McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 269.

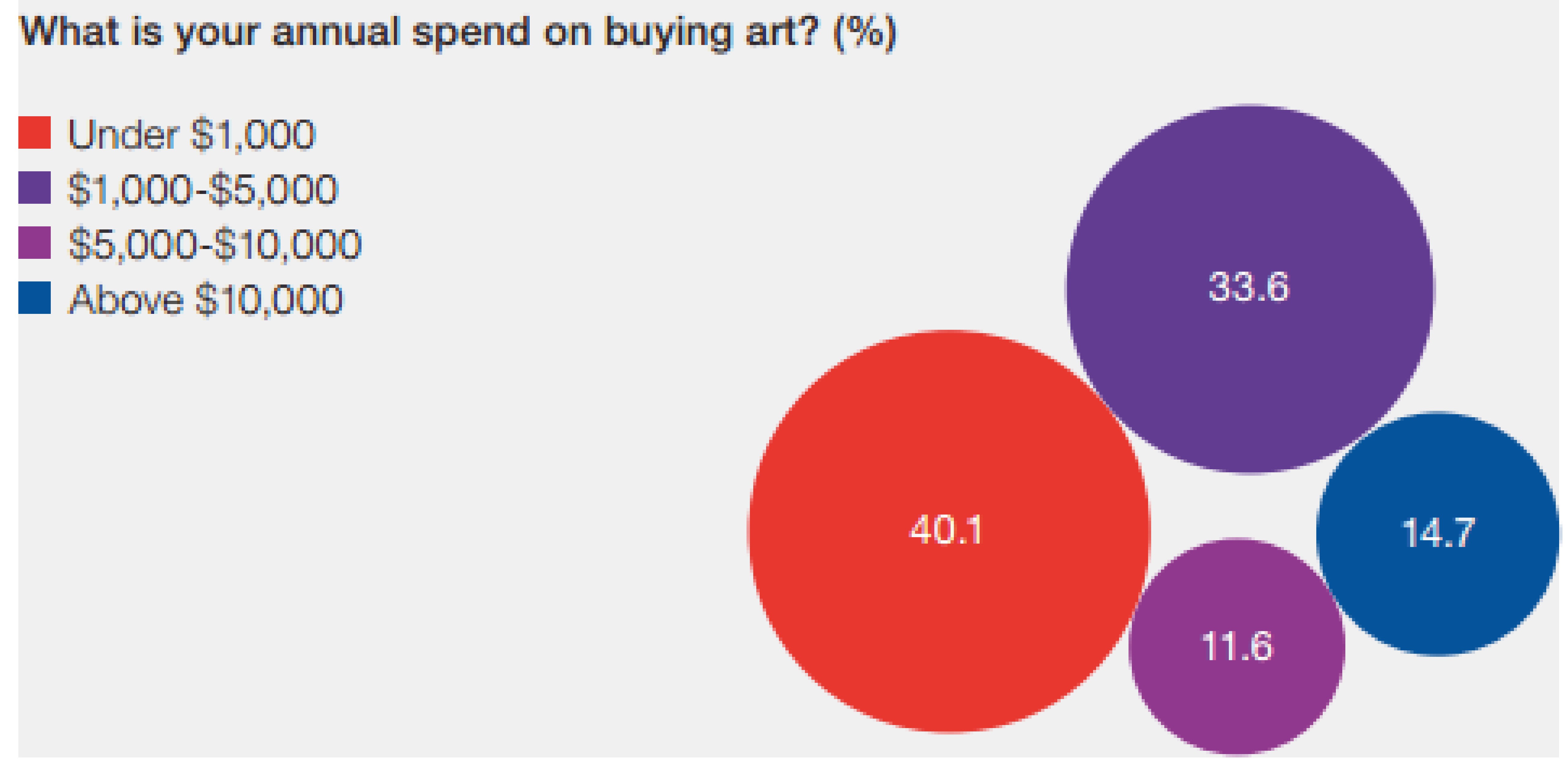

Obviously, there is a correlation between the bottom-tier buyers and the younger generations, who form the core clientele of online shops. Hiscox’s 2018 survey of the shopping behavior of Generation Y found that 40% of the online clientele spend under $1,000 per year, and 73% spend less than $5,000 (Table 5).38 This data brings us back to the comparison between volume and value, indicating that the online art market is largely identified with the lower classes, namely the majority of the clientele, who represent volume (quantity) rather than value (capital).

Table 5: Generation Y, quoted from Hiscox online art trade report 2018, available online https://www.hiscox.co.uk/sites/uk/files/documents/2018-04/Hiscox-online-art-trade-report-2018.pdf, 26.

Yet although on the surface it seems that the online market reflects the characteristics of the general art market, and that no radical change can be expected in the near future, two additional factors need to be taken into consideration: the first is that the millennials and the Zs are still young. Some of them will grow to be the millionaires of the future and become art collectors, and they will bring along their shopping habits, which might pull the online market towards the center. Second, the online market, as I would like to argue, did manage to create a change in the art market that might prove significant in the future by engendering another sub-market, which in this case is centered on “smallness”. Collectors under the age of thirty-five that use the online selling venues include a substantial number of new consumers, due both to the expansion of possible shopping platforms and to their accessibility. In that sense, the online market has already made a change by exponentially increasing the number of low-cost artworks that suit the budget of the lower classes. This inflation of low-cost works can be perceived as creating a wide yet low-value sub-market of “smallness”, revolving around small money, small clients, and small artworks. A major catalyst for the emergence of this construct has been celebrity culture and the circulation of art-world brand names such as Hirst, Koons and Murakami, which has been facilitated through the internet. The change evident in the market is thus not necessarily centered on content, but rather on a new economic code for art. As Pamela Lee has demonstrated in examining the case of Takashi Murakami, this economic code can be theorized through the concept of scale, which in turn can also be translated into monetary value.39 The entrance of superstar artists to the arena of mass production through the sale of online prints, small paintings, printed bags, signed accessories and much more, has enabled everyone to feel as if they are participating in the market of “bigness” by owning “a Murakami” or “a Koons” – a real object that comes from the terrain of the big players. This practice, in turn, enhances the paradox of neoliberalism, according to which the masses are led to believe they are a part of the game, even though in reality they are marginal to it.

This market of smallness, one might argue, supports the market of bigness rather than offering an alternative to it; yet in relation to the major part of the society, one possibility of change in the future derives from the discursive structure of the internet. While considering a Murakami print for $300, the client is presented with other works, from outside of the circle of bigness. With an added expansion of the young clientele, the online market might bring about new conceptualizations of aesthetic education, connoisseurship, and political authority. Museums and curators have lost their authority to the market: the choice of exhibitions, even in big museums, is today increasingly driven by financial considerations, and manipulated by private money. One might even suggest that online platforms will thus assume the role previously assigned to museums – that of educating the audience and introducing to it emerging artists. Significantly, participants in the market – including the lower classes – increasingly believe (albeit, for now, mistakenly) that they form part of the new tastemakers. Even if we are currently unable to visualize this shift, the profound change in concepts so critical to the field, such as connoisseurship and validation, cannot be dismissed. Such a development might offer a chance to increase equality and true participation through empowering the middle and low classes and strengthening their ability to engage in the market effectively and to make a significant political contribution.

There remains much that we still cannot predict about how the online market will affect the general market. Suffice it to mention Paddle8’s recent merger with The Native and the introduction of Crypto-Auctions which allow the use of crypto-currencies like Bitcoin.40 One may also consider the introduction of AI, and of VR and AR technologies41, or financial solutions such as the possibility of group purchases through crowd-funding and platforms like Kickstarter, which simulate the division of the artwork into stocks owned by a public. These are just a few other options made possible by the internet that could increase the opening of the market and the active involvement of the lower classes. Pure equality does not seem to be an option in a neoliberal environment lacking regulation of concentration tendencies. Yet if we settle for degrees of equality, online platforms do seem to have the possibility of moralizing the art field through a more equal structure of the field’s activities and participants.

The model I have presented here builds on Bourdieu’s theorization of the cultural field as involving economic, social and political parameters that constantly affect each other, while adding to it a critical perspective that draws on the field of moral economics. Since the art world performs as part of the general world and complies with its conditions and codes, it is not surprising that we recognize within both the art world and the art market a series of economic, social and political developments similar to the ones unfolding more generally in the world. In presenting the art market and related economic data from a social perspective, I have also sought to provide a somewhat positive forecast, predicting the possibility of resistance to the decreasing amount of equality and social accessibility which has characterized Western societies in recent years. The internet does not provide a promise for a brighter future in terms of political policy, but it does offer a potential improvement of the situation, and a possible restraint of current tendencies that result from neoliberal models. Online platforms, which are by definition social platforms, carry the possibility of challenging economic and political forces, and leading to a more ethical balance.

Ronit Milano is a senior lecturer at the Department of the Arts in Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel, where she is head of the Museum Studies programme.

1 Pamela M. Lee, Forgetting the Art World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012).

2 For Bourdieu’s most important publications in the context of my argument, see: Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste (1979), trans. Richard Nice (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984); Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed, in Poetics 12, Issues 4–5 (November 1983), 311-356.

3 Clare McAndrew (Art Economics), The Art Market 2019: An Art Basel & UBS Report, 28. Available online at: https://www.ubs.com/global/en/about_ubs/art/2019/art-basel.html. Accessed 25 March 2019.

4 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 144.

5 In the context of the competition between the two auction houses, see: Don Thompson, Why Sotheby’s and Christie’s Don’t Operate Like Other Duopolies, in Artsy, 24 November 2016. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-why-sotheby-s-and-christie-s-don-t-operate-like-other-duopolies. Accessed 3 October 2018.

6 On the results of the changes in control over information due to the internet, see: House Pride: The Art World Is Changing Faster than Sotheby’s and Christie’s Are Adapting their Business Model, in The Economist, 28 January 2016. https://www.economist.com/business/2016/01/28/house-pride. Accessed 3 October 2018.

7 Naomi Klein, No Space, No Choice, No Jobs, No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies (New York: Picador, 1999). Republished under various titles – best known as No Logo; and Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Picador, 2007).

8 Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production.

9 Milton Friedman, “Economic Freedom, Human Freedom, Political Freedom.” Lecture delivered at the Smith Center in 1991. Available at: http://www.calculemus.org/lect/07pol-gosp/frlect.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2018.

10 Orley Ashenfelter and Kathryn Graddy analyze the famous Christie’s-Sotheby’s price-fixing scandal, and show – as I rationalize later on in my essay – that it is unlikely that successful buyers as a group were injured: Ashenfelter and Graddy, Anatomy of the Rise and Fall of a Price-Fixing Conspiracy: Auctions at Sotheby’s and Christies’s, in Journal of Competition Law & Economic 1, 1 (March 2005), http://www.nber.org/papers/w10795.pdf. Accessed 3 October 2018.

11 Noteworthy efforts for self-regulation include the RAM (Responsible Art Market) initiative, in which Christie’s is one of the founding partners. See: http://responsibleartmarket.org/. Accessed 3 October 2018.

12 Alasdair C. MacIntyre, After Virtue (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1981), 181.

13 Another, more complicated model would build on Terry Smith’s concept of contemporaneity. Smith delineates what he sees as the tripartite structure of the art world, which represents different currents. The first current is what he terms “institutionalized Contemporary Art”, which complies with the conditions of neoliberal economies and art institutions in First-World countries. The second and third currents, according to Smith, relate, respectively, to former colonial countries and to small-scale and independent art initiatives. Whereas the first current perfectly suits the characteristics of what is perceived as the core of the art market, Smith’s two other currents represent the parts of the market that are relegated to the margins, or even excluded from it completely. Smith, Contemporary Art: World Currents (London: Laurence King, 2011).

14 Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report 2018, 9. Available online at: https://www.credit-suisse.com/corporate/en/research/research-institute/global-wealth-report.html.

15 Clare McAndrew (Art Economics), The Art Market 2019: An Art Basel & UBS Report, 262.

16 It is worth noting again that this is an estimation: the numbers accurately represent the volume of artworks, which – based on price accessibility – I relate to classes and buyers.

17 Antoine Hennion, A Plea for Responsible Art: Politics, the Market, Creation, in Victoria D. Alexander, Samuli Hägg, Simo Häyrynen and Erkki Sevänen, eds., Art and the Challenge of Market, Volume 2 (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 145-169.

18 Hennion, A Plea for Responsible Art, 146.

19 John Zarobell, Art and the Global Economy (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 219.

20 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 49.

21 McAndrew, The Art Market 2018, 45.

22 Isabelle Graw, High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture (Berlin and New York: Sternberg Press, 2009).

23 Ronit Milano, “The Commodification of the Contemporary Artist and High-Profile Solo Exhibitions: The Case of Takashi Murakami,” in Re-envisioning the Contemporary Art Canon: Perspectives in a Global World, ed. Ruth E. Iskin, (Routledge: London and New York, 2017), 239-251.

24 Ronit Milano,The Rise of the Monographic Exhibition: The Political Economy of Contemporary Art, in Maia Wellington Gahtan and Donatella Pegazzano, eds., Monographic Exhibitions and the History of Art, (Routledge: London and New York, 2018), 282-291.

25 Olav Velthuis, Symbolic Meanings of Prices: Constructing the Value of Contemporary Art in Amsterdam and New York Galleries, in Theory and Society 32 (2003), 181-215. Reprinted in Velthuis, Talking Prices: Symbolic Meanings of Prices on the Market for Contemporary Art (Princeton, N.J. and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2007), 158-178.

26 Jeremy Gilbert describes this illusion as essential to the stability of neoliberalism in What Kind of Thing is ‘Neoliberalism’? in Neoliberal Culture (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 2016 [2013]), 10-32.

27 Paco Barragán, Neo-modernity, Neo-biennalism, Neo-fairism, in Valerio Terraroli, ed., 2000 and Beyond: Contemporary Tendencies, vol. 5 of The Art of the Twentieth Century series (Milan: Skira, 2010), 275-291. Excerpts reprinted in Titia Hulst, ed., A History of the Western Art Market: A Sourcebook of Writings on Artists, Dealers, and Markets (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 371-374.

28 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 258. There are slight differences between Art Basel-UBS’s report (section on e-commerce) and the Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2019.

29 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 272.

30 Data taken from Crunchbase, at: https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/art-sy#section-funding-rounds. Accessed 3 October 2018.

31 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 274.

32 Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2019, 7. Available at: https://www.hiscox.co.uk/online-art-trade-report. Accessed 10 April 2019.

33 Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2018, 9.

34 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 282.

35 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 283.

36 Molly Schuetz, New York’s Artsy Is Making It Even Easier to Buy Art Online, in Bloomberg, 27 March 2018. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-03-27/new-york-s-artsy-is-making-it-even-easier-to-buy-art-online. Accessed 3 October 2018.

37 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 269.

38 Hiscox Online Art Trade Report 2018, 26.

39 Economies of Scale: Pamela M. Lee on Takashi Murakami’sTechnics, in Artforum (October 2007), 336–343.

40 For instance, see: Gabriella Angeleti, Paddle8 to Allow Cryptocurrency in Online Auctions, The Art Newspaper, 23 January 2018. Available at: https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/paddle8-paves-the-way-for-cryptocurrency-in-online-auctions. Accessed 3 October 2018; See also: McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 295-297.

41 McAndrew, The Art Market 2019, 300-303.