ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Caroline Flick

Among the archival records pertaining to the Berlin Head Office of the National Socialist Reich’s Chamber of Fine Arts a list of forty-four art dealers’ names for registration with the new Chamber can be found. The focus of this article is on events surrounding this archival record, dealing exclusively with the trade section within the Reich’s Chamber of Fine Art and focusing on individuals rather than firms. The Reich’s Chamber of Culture was established in order to standardise “cultural creation”, with its jurisdiction ultimately empowered to cover activities of art production, reception and distribution. As the Weimar Republic was transformed into a totalitarian state, the Reich’s Chamber of Culture was created by evoking the nomenclature of Chambers of Commerce and trading regulations but intending direct control of individuals as well as activities. As a consequence, its influence was felt throughout the entire art market and initiated a market disturbance which reverberates to the present time, necessitating ongoing market research and price analysis. The dealers whose professional activities were controlled by the new licensing regulation developed different strategies to mitigate its effects, ultimately demonstrating a limited measure of agency under a totalitarian regime.

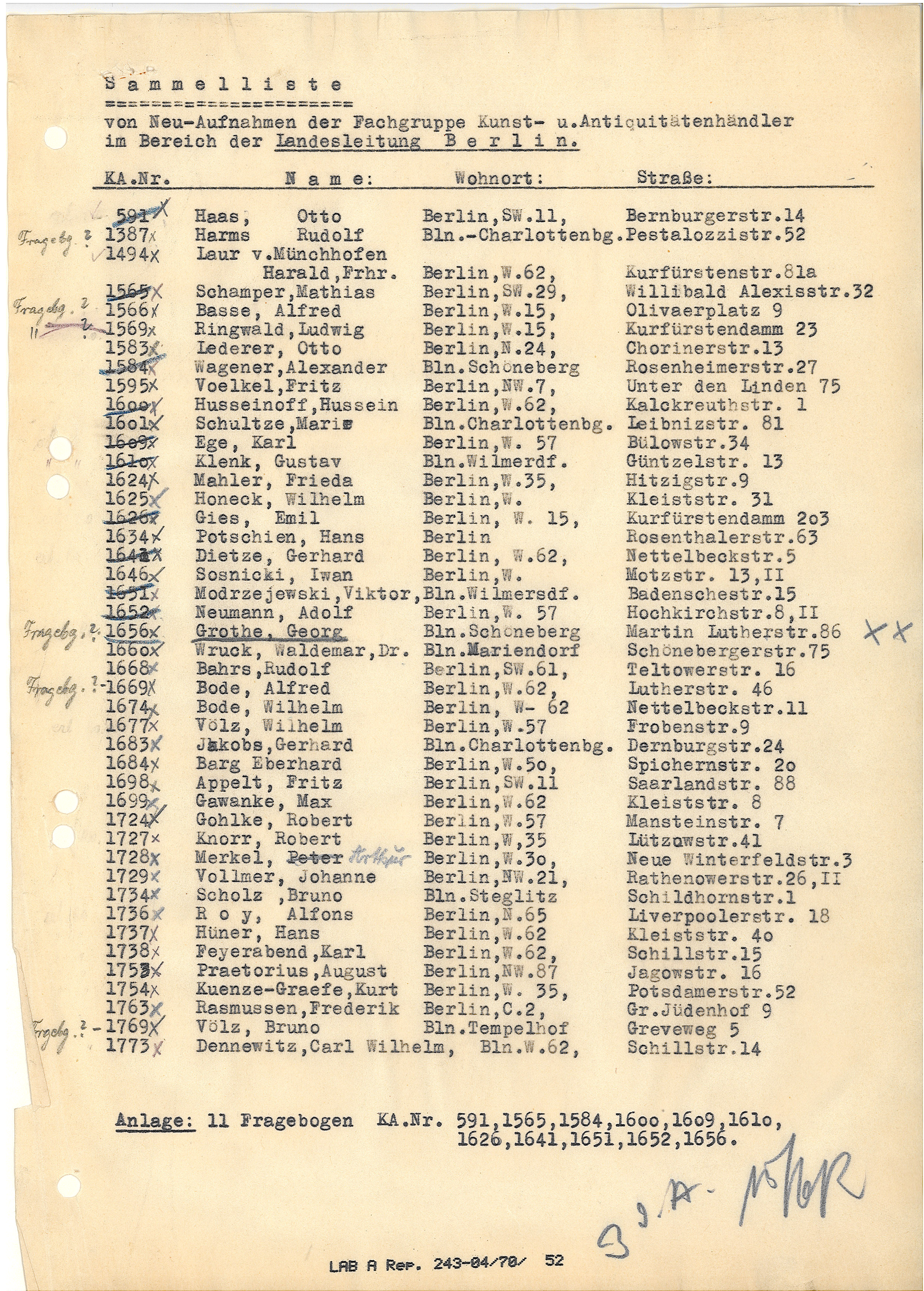

The archival records of the Berlin Head Office of the National Socialist Reich’s Chamber of Fine Arts are only preserved in part. Nevertheless, there are lists which indicate an increased level of bureaucratic activity in the second half of the year 1935.1 These documents include a “Collective Listing of New Applicants in the Professional Group for Art and Antiques Dealers”, comprising forty-four names. (Fig.1) It was dated by the Berlin policy officer in handwriting only with “15/6” as he filed it away.2 This list raised a question about what had happened before it was compiled, and even more importantly, what came to pass afterwards. Why would these dealers apply, and what further fate befell them?3

Fig. 1: List of new entrants in the group of Art and Antiques, section Berlin, undated (15 June 1935);

Landesarchiv A Rep. 243-04 no. 70.

The list gives a comprehensive overview of a wide range of dealers, from agents for decorative paintings and commissions to recognised experts, and from entrepreneurs who were new to the business to those who were self-employed as a result of “Aryanisation”, and those who had emigrated. As a group, they were as heterogeneous as the artistic community, with a trading territory demarcated by the cornerstones of modern, undesirable art and in-demand classical art, with business entities ranging from micro-enterprises to notable firms.4 All of them were confronted with the same new regulations.5 The price they had to pay varied greatly, from government interference and surveillance to racist enforcement of business closure, leading to a loss of purpose in life and, for more than a few, to a loss of life itself.

In order to look more closely at the events surrounding this dry archival record, I would like to make use of a model to facilitate a comprehensive perspective of my ongoing research about, to date, more than 160 files on Berlin art dealers relating to the Chamber. This article will deal exclusively with the Berlin trade section within the Reich’s Chamber of Fine Art.6

The Reich’s Chamber of Culture was established in order to standardise “cultural creation”, that is, activities of contemporary art production and reception. Its early definition of “art” as a commodity, however, not only subjected contemporary art-making but also cultural goods from before 1850 to its jurisdiction.7 As a consequence, its influence was felt throughout the entire art market and initiated a market disturbance which reverberates to the present time, necessitating market research and price analysis.

Through adopting the nomenclature of “Chamber”, the new organisation suggested a familiar model. It evoked the reassuring image of the Chamber of Commerce, a self-administrative organ of business people in a region, who would support and maintain the local economic network. In this model, which had been established since the nineteenth century, members of the board and committees were chosen in free elections every six years. They set the budget, prepared reports and organised public conferences. So that everybody was represented and would have the opportunity to speak freely about decisions to be taken, membership was obligatory. To ensure adherence, the organisation’s running costs were levied together with taxes. The Ministry of Trade represented merely a legal supervisory body.8

As the Weimar Republic was transformed into a totalitarian state, this type of “Chamber” was completely deformed. By mid-1934, the Chambers of Commerce were bundled into so-called Economic Chambers, whose president was appointed by the minister. In a vertical hierarchy based on the “Führerprinzip”, this president was empowered to appoint his own advisory board and also set up procedural rules, executed by a civil servant manager. Elements which replicated the original were of course obligatory membership and the automatic collection of fees.9

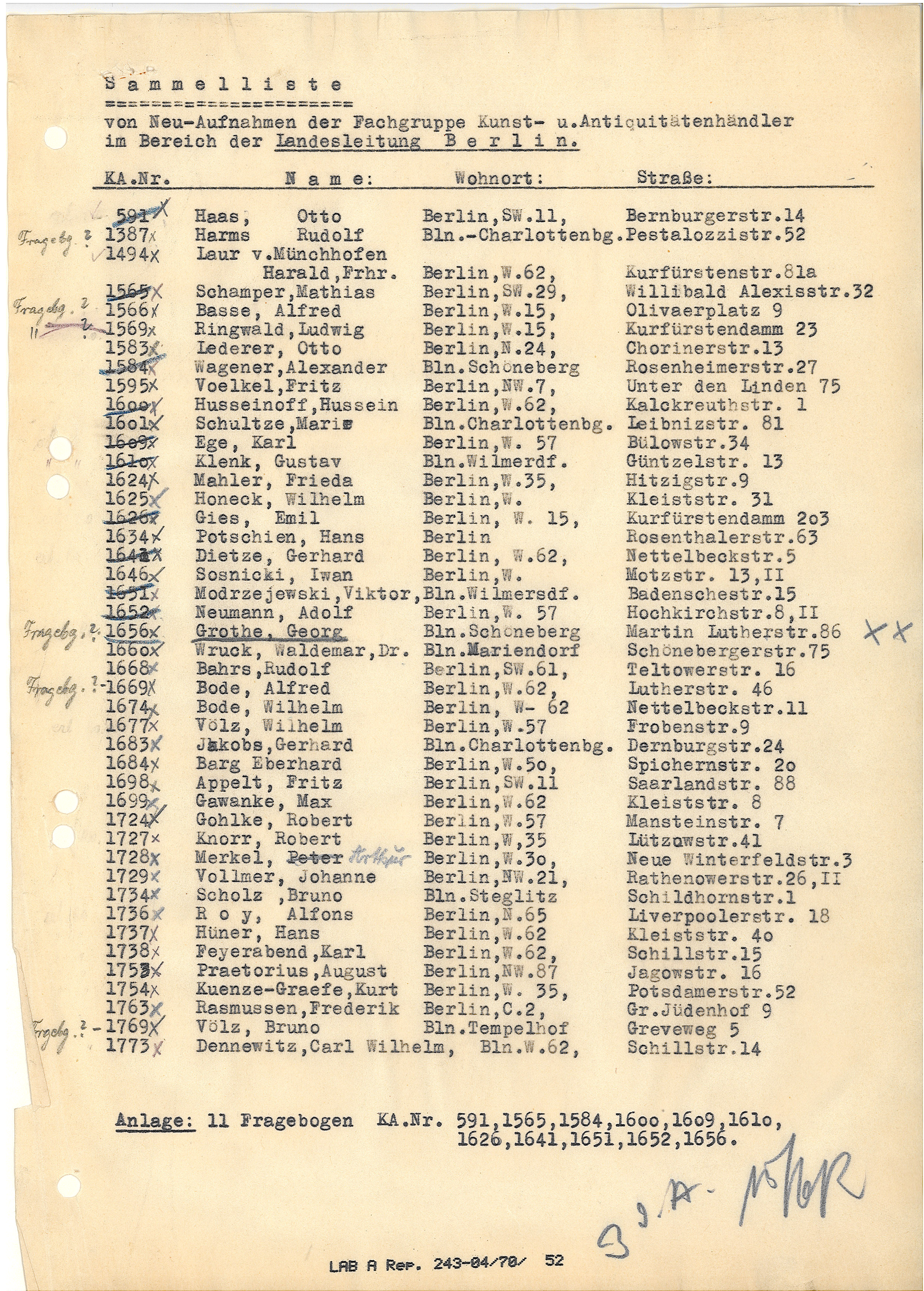

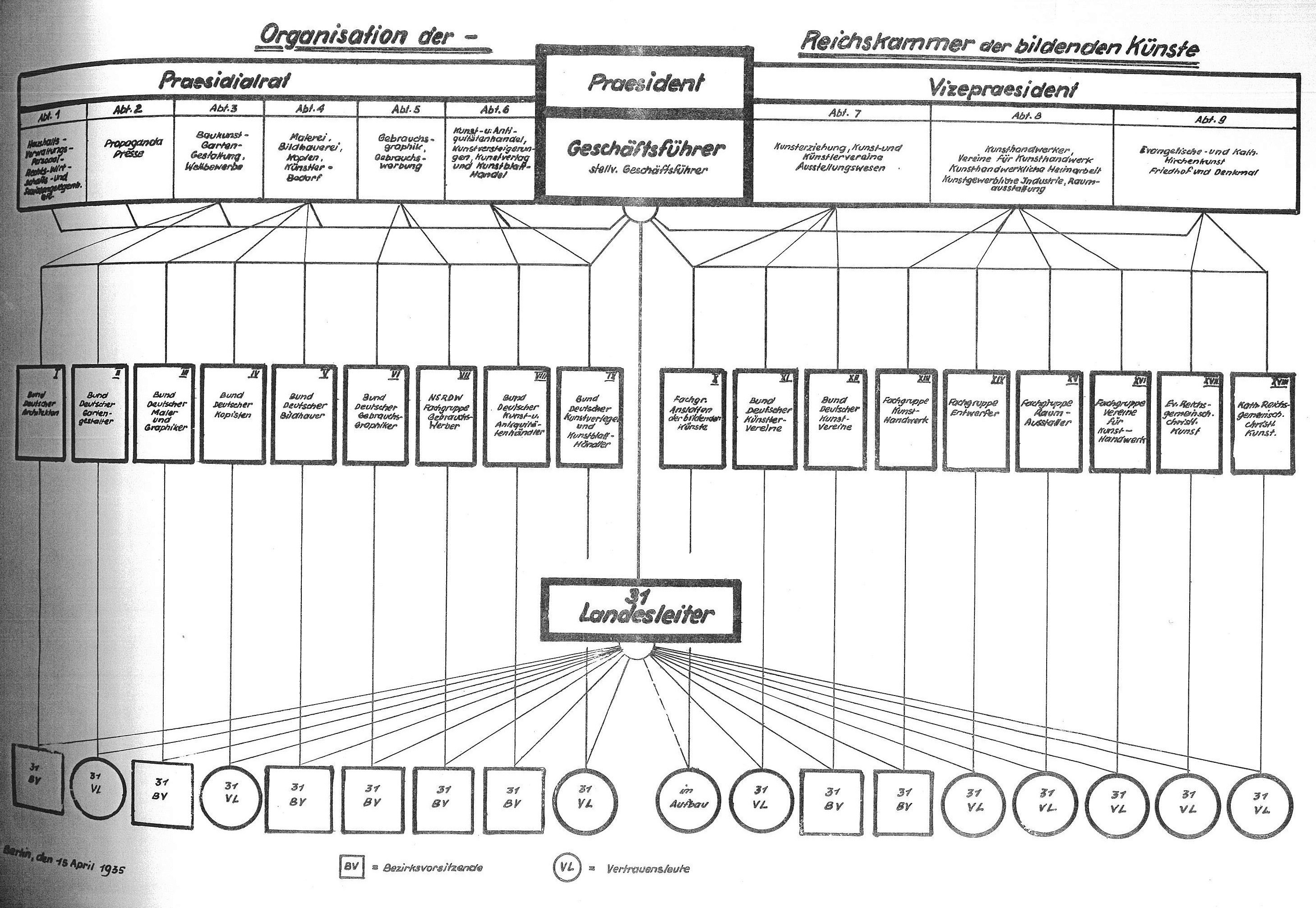

Such a distorted Chamber provided neither representation nor self-administration. Along these lines, the Reich’s Chamber of Culture was established as an instrument of directional governance, set up in parallel to the “Economic Chambers”, as already indicated in the Chamber constitution of 1935 (fig. 2), an objective which becomes even clearer after the vertical restructuring in 1936 (fig. 3).10 The purpose of the organisation was a subjugation of its sectors to trading regulations.

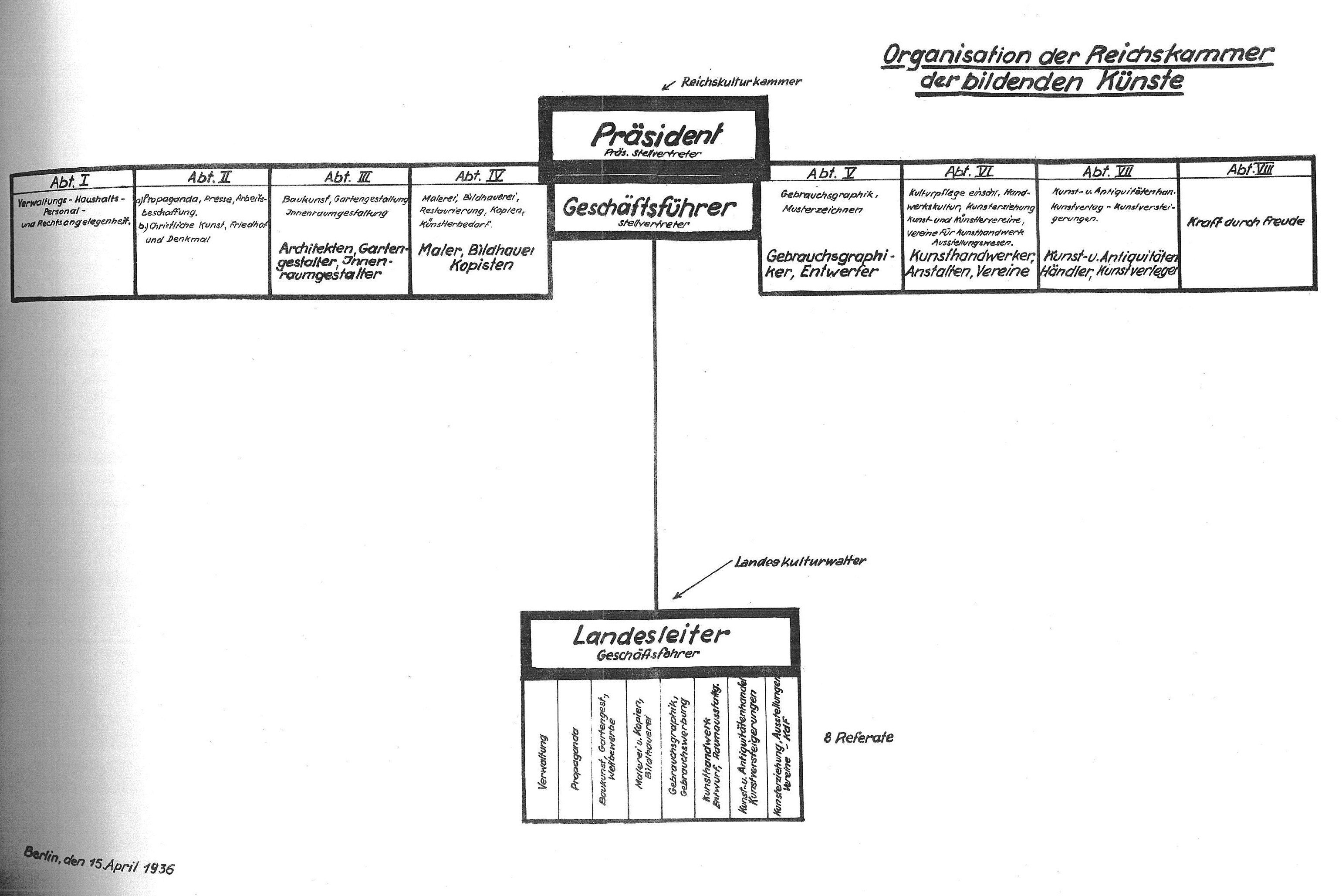

Following the former Chamber of Commerce model in principle, the foundation act of the Chamber in September 1933 interpreted compulsory membership as a consequence of professional practice. An explicit inversion of this condition made membership a “prerequisite of professional practice”. This volte-face was buried in the wording of the legislation (fig. 4), in a paragraph on deadline regulations, and was confirmed by the administrative decree for the protection of profession in 1934.11

Fig. 2: Organisational chart of the Reich’s Chamber of Fine Arts, 1935, including sub-sections

Reichskulturkammer (printed typoscript), undated (15 April 1935).

It follows that we have here a permission, a license to enter the market, that was granted by membership in the Chamber and could also be taken away by it. The metamorphosis of the Reich’s Chamber to an office of authorisation is part of the conversion of a former “legislation to permit with reservations to forbid” towards a “legislation to forbid with reservations to permit” under the National Socialist regime.12

Freedom of trade in the nineteenth century required licensing for very few professions, for example handling dangerous goods. Since 1845, the German trade regulations had adopted traditional admission criteria.13 In this instance, the newly subjected professions were to be extensively and comprehensively regulated after 1933, to the point of strangulation.

Fig. 3: Organisational chart of the Reich’s Chamber for Fine Arts in 1936 after verticalisation;

Reichskulturkammer (printed typoskript), undated (15 April 1936); in Die Kammer schreibt, 22f.

As early as November 1933, the Chamber of Culture firmly established the formula for acceptance or exclusion “if there are facts which suggest that the person in question does not have the reliability and suitability required for the performance of the profession”.14 If “facts presented” could lead to an admission being withheld, the reasons for failure would need to be provided by the office of authorisation – the burden of proof did not lie with the applicant. These formulae appeared within the licensing procedures from the outset. What was novel about the approach was not so much that drastic action was taken against individuals, but rather the application of such actions to the professions related to the arts.

Fig. 4: “Integration” as a future prerequisite for professional practice; Zweite Verordnung zur Durchführung des Reichskulturkammergesetzes. Vom 9. November 1933, RGBl 1993 I 969;

http://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/alex?aid=dra&datum=1933&size=45&page=1094.

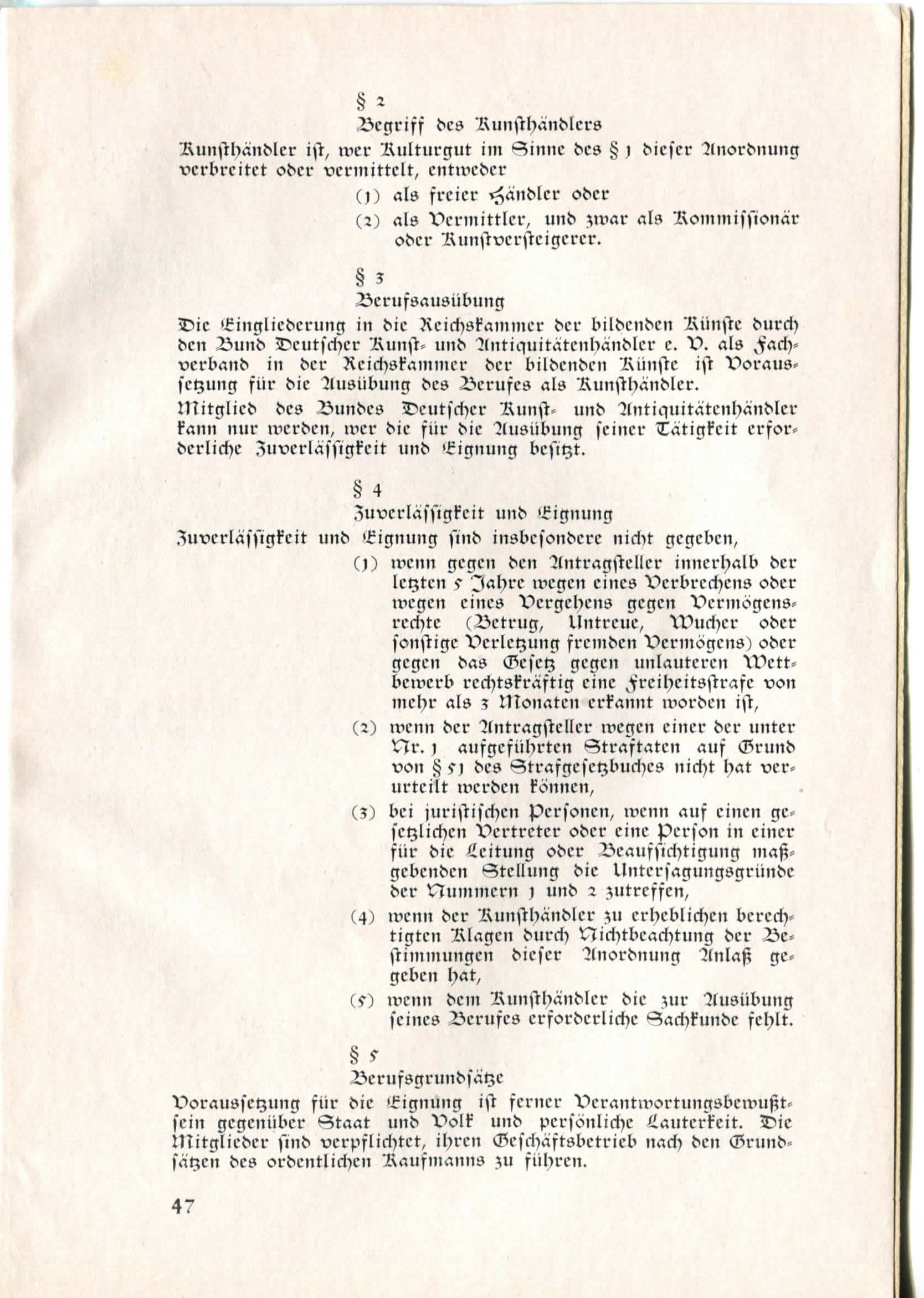

The admission criteria were set by the administrative order for the protection of profession for arts and antiques dealers of August 1934. As was customary practice, paragraph 4 lists five points relating to the “reliability” – explained as the absence of a criminal record or offences against property –, and “suitability” – explained as sufficient expertise, knowledge of the business and commercial knowledge (fig.5).

In practice, however, these criteria were treated to some extent as negotiable. A dealer with previous convictions for fraud and gambling debt could certainly be said to fail on the grounds of professional respectability. Accordingly, the police president pressed for intervention but the Chamber’s local head office decided to ignore the facts. One dealer with four previous convictions and one acquittal not only managed to become policy officer for Berlin, but was also granted his license without further ado.15

Other police records based on the legal framework of the time did not stand in the way of holding a licence. These concerned rulings following paragraph 175 of the German penal code, criminalising homosexual activities. The art historian Christian Isermeyer remembers that the art dealer Hanns Krenz – who must have stood trial for being gay – had always refused to discuss this matter. Files are missing. In another case, even though bankruptcy ensued, due to the prolonged prison sentence of the business partner, the license was also not rescinded.16

Fig. 5: Decree for the Protection of Profession, dated 4 August 1934, in Schriftenreihe der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, published by the president of the R.d.b.K., Heft 1 (1934), 46-48, 47;

Stefan Pucks, Berlin (private collection).

In contrast, the criteria of suitability were actually applied. In the late summer of 1935 the Arts Chamber refused a license to a few small dealers, due to lack of “sufficient professional experience”.17 Having said that, at the end of the year Goebbels proclaimed that everybody had to be accepted in his stated profession without any further examination. This political change of direction put paid to the Chamber’s ambitions for quality control. Its objective was an enlargement of the economic base, as well as direct control of each and any artistic activity and distribution of its products. The Arts Chamber had been informed about this directive in advance by the end of October 1935 – by December, the aforementioned dealers had been accepted as members.18

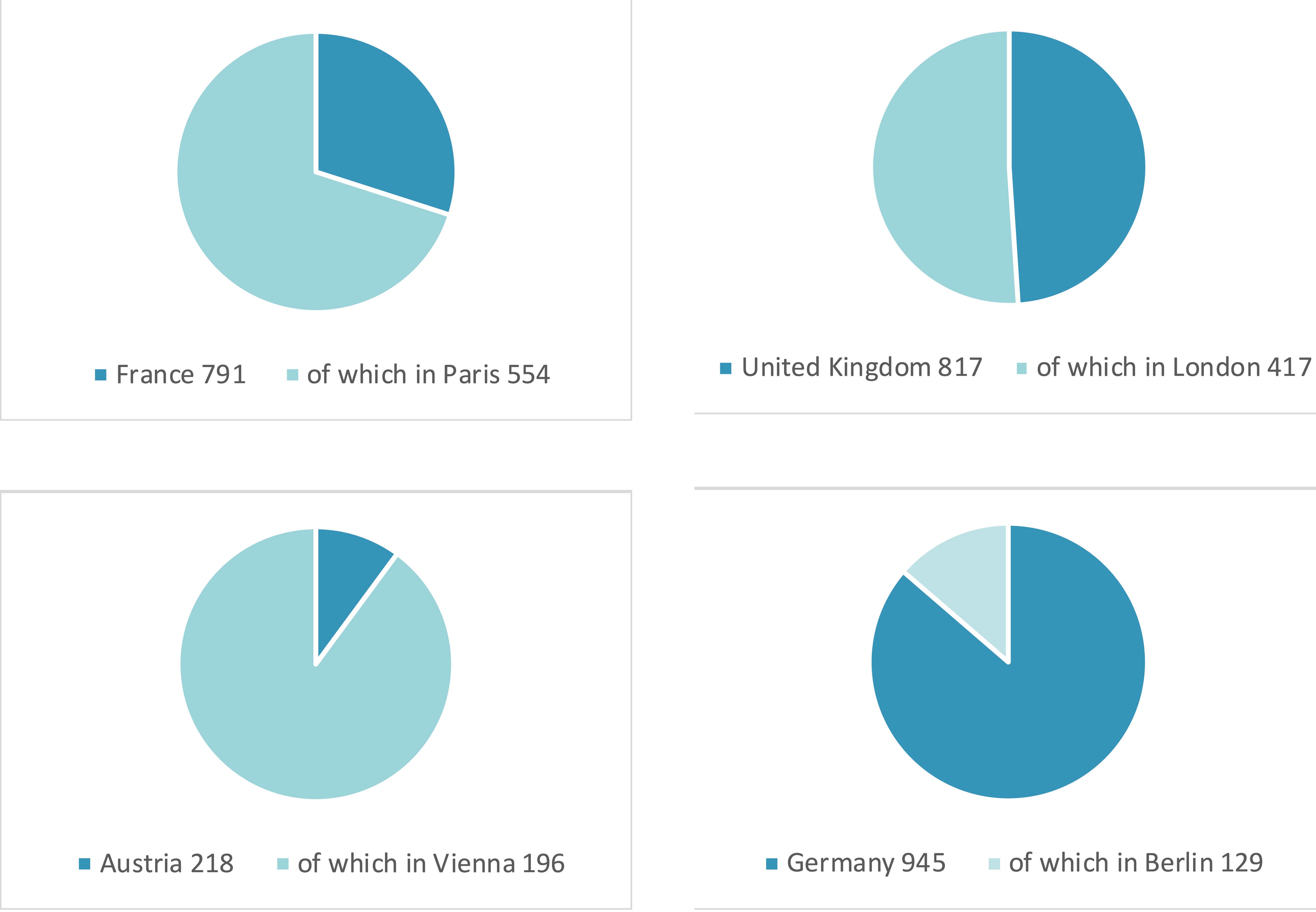

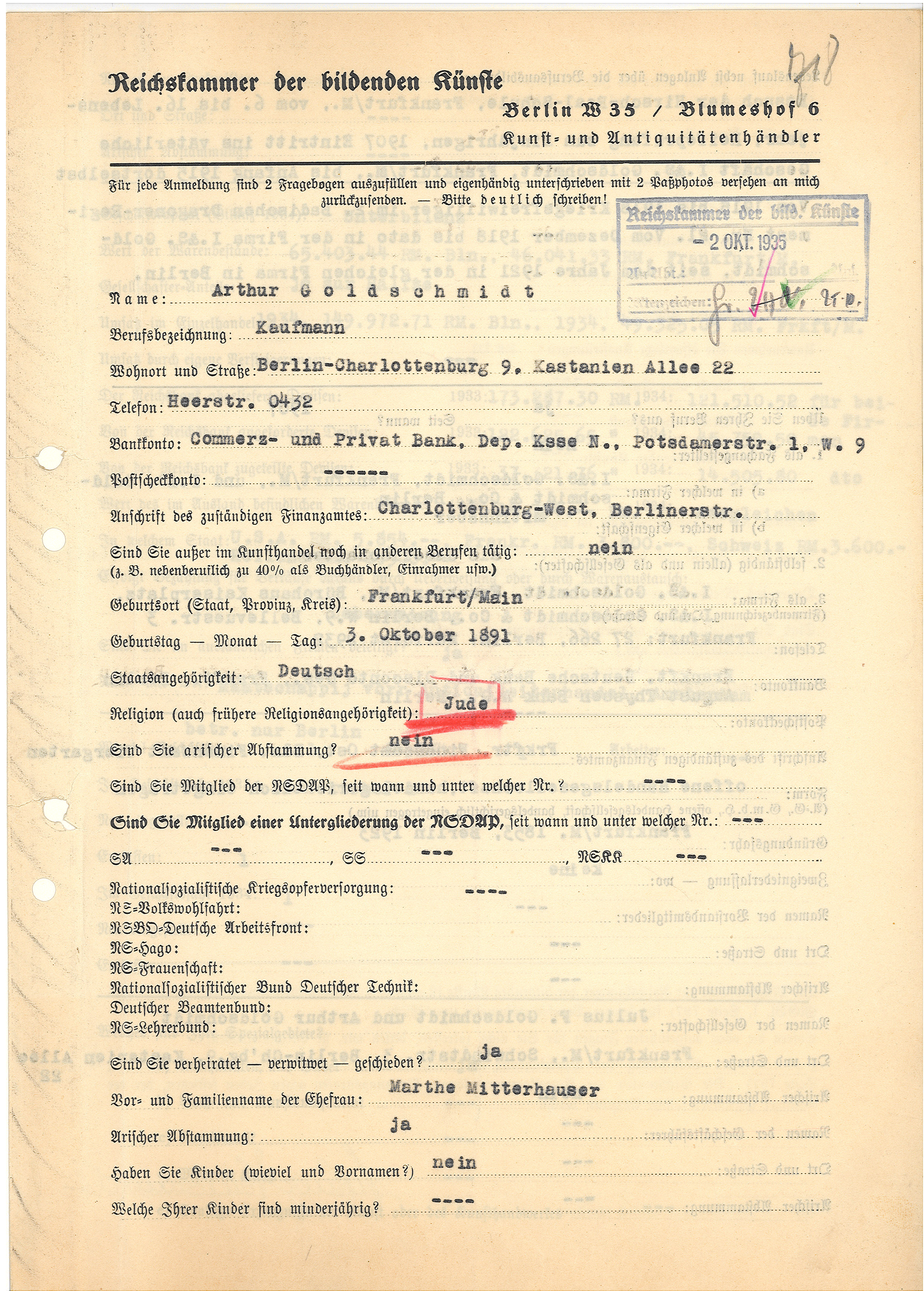

It is worth bearing in mind that Germany’s art trade differs from centralised countries, such as France, England or Austria, in that the art trade was not concentrated to a large extent in a single urban centre. A directory of 1932 confirms this wider distribution (fig. 6), which reflects the German historic structure of small states and late founding of the Reich (fig. 7).

Nevertheless, two centres had emerged, drawing on the importance of the respective city in its former monarchy and its attraction to neighbouring counties. In a 1933 directory of 945 art dealers, Berlin stands out with 129, and Munich with 92. Meanwhile, even with a large gap, 20 to 50 dealers are still listed for each of the next bigger locations, many of them former residences of ruling houses (fig. 8).19

Fig. 6: Art dealers in European countries and capitals: France, United Kingdom, Austria, Germany; author’s own calculations based on: Internationales Adressbuch des Altkunst- und Antiquitätenhandels (Weimar 1933).

Consequently, at its point of inception, the Reich’s Fine Art Chamber’s 320 members comprised less than 15% of the 2,074 dealers listed in 1934 official statistics.20 They joined the Chamber at the end of 1933 via an association which changed its name several times, finally known as the “Bund Deutscher Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler”.21 This enforced compliance had been instigated by the notorious Julius Streicher, chair of the Central Committee to Repulse Jewish Atrocity and Boycott Agitation, who felt that the board of the previously established renowned main art dealers’ association had been “overrun by Jews”.22 Several regional associations and other driving bodies had been made to toe the official line by the chair of this newly founded art dealers association, the Munich auctioneer Adolf Weinmüller.23

Figs. 7 and 8: Distribution of the art trade across cities; author’s own calculations based on: Internationales Adressbuch des Altkunst- und Antiquitätenhandels (Weimar 1933).

The Association of German Art and Antiquities Dealers was nominally a society, but in fact a hierarchical structure. It was now tasked with recruiting.24 Regional representatives visited applicants and made enquiries. Both their nomination and their vote can be regarded as co-optation, since they were chosen by officially appointed representatives and awarded the license to applicants. Both the vote and the appointment lacked transparency and must be attributed to self-empowerment. Co-optation recruits its own kind, but no rejection is known from this intermediate period either and was perhaps also not an option.25

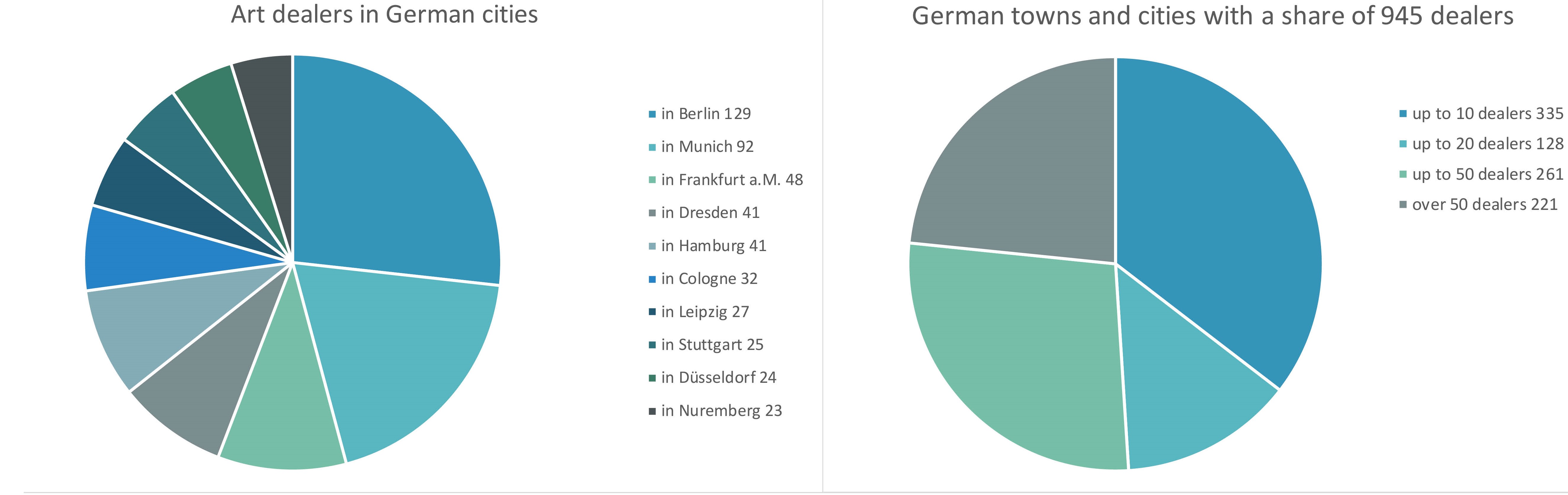

The licensing process was formalised from spring 1934 through the establishment of specialist administration in the head office of the Fine Arts Chamber, staffed in line with party membership.26 Dealers who had not been part of the classical clientele of the associations seemed to be in no hurry to enrol – perhaps they did not feel that the requirement applied to them or they did not take the new organisation particularly seriously.27 But at this point, admittance criteria became pernicious. The admission questionnaire asked about characteristics relevant to the profession, such as place of residence and business address, associations including party membership and religious confession, marital status, education, legal entity, capital and turnover.

The questionnaire pre-empted an anti-Semitic selection. The forms show “race” being listed independently of “confession”. The documents also show that completed forms were marked-up afterwards in this field – sometimes two or three times. The membership number at the top was marked first in pencil, possibly with the receipt stamp (fig. 9). In other cases, subsequent top markings are likely to have been made during revisions, added to control relegation and surveillance.28

The dissolution of the associations on 30 June 1935 – preceding the Nuremberg racial laws by several weeks – liquidated all of these societies.29 As the intermediary function of the societies was eliminated, the ensuing verticalisation (see above, fig. 3) resulted in all members becoming direct underlings of the Chamber. As the institution was terminated, membership ceased and the license was lost.

Fig. 9: Multiple annotations under “Abstammung [ancestry]”; Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten Berlin, A Rep. 243-04 no. 2617 Arthur Goldschmidt.

While the majority of art dealers subsequently received immediate confirmation of their Chamber membership, former licensees could be treated as applicants and become subject to a supposed re-examination. The protection of profession had been tied to an additional criterion inserted under paragraph 5, which was “Responsibility towards the People and the Reich” (fig. 10), converting the Chamber’s purpose into that of the individual. The rejection notice could now refer to this “Responsibility” entirely independently of professional criteria. Indeed, an application could be rejected even if the latter were completely satisfactory: “I was unable to identify particular facts which speak against Haas’ reliability and suitability. Nevertheless, I consider H. unreliable as a Non-Aryan”, the Berlin manager wrote in September 1935.30 Before the end of the year 1935, it was also stated explicitly that “as a Jew” one could not assume such responsibility.31 The enforcement applied to individuals was now – in contrast to the trade regulation’s criteria for obtaining a license – based on their perceived personal attributes rather than their actions – a National Socialist procedure of exclusion.32

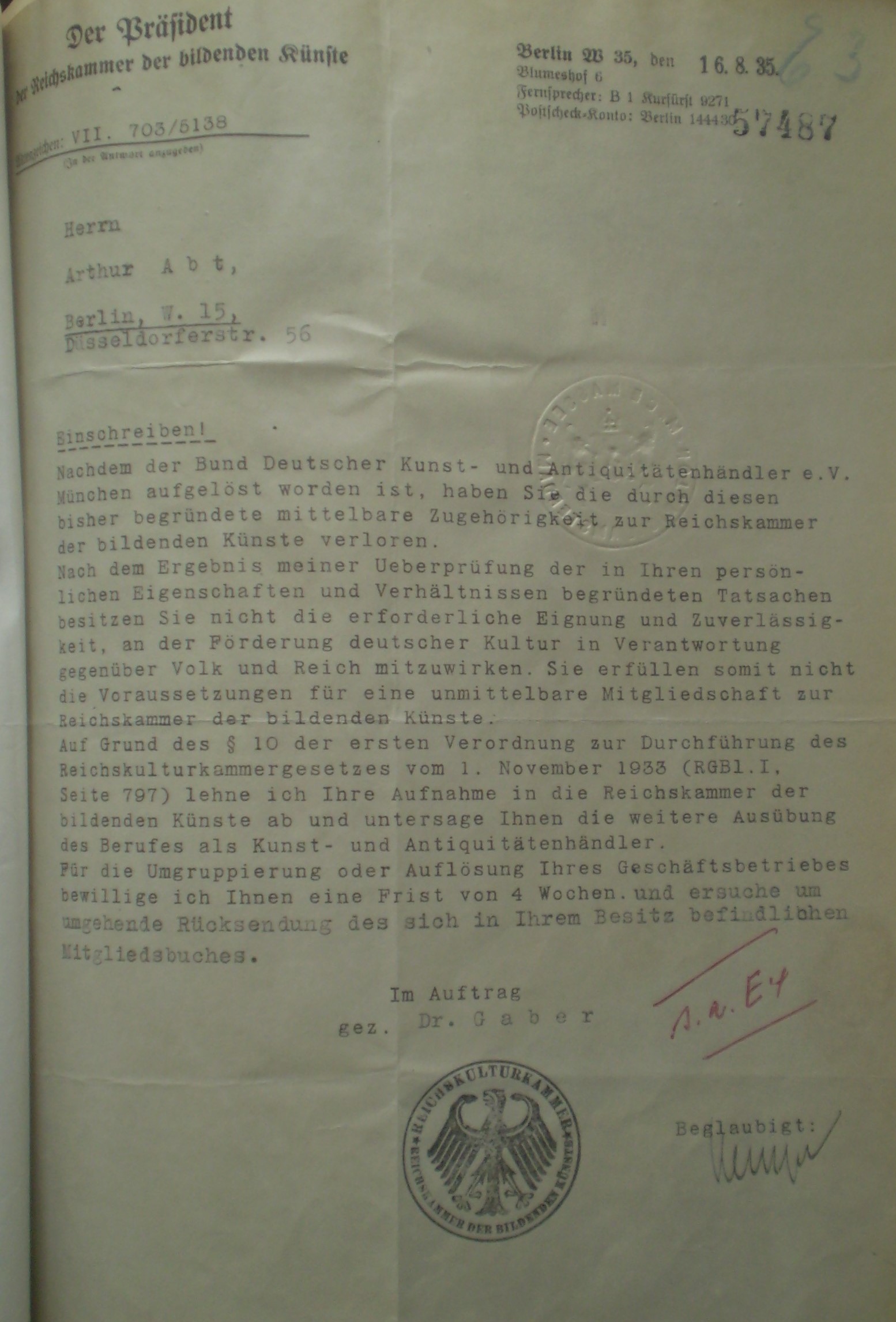

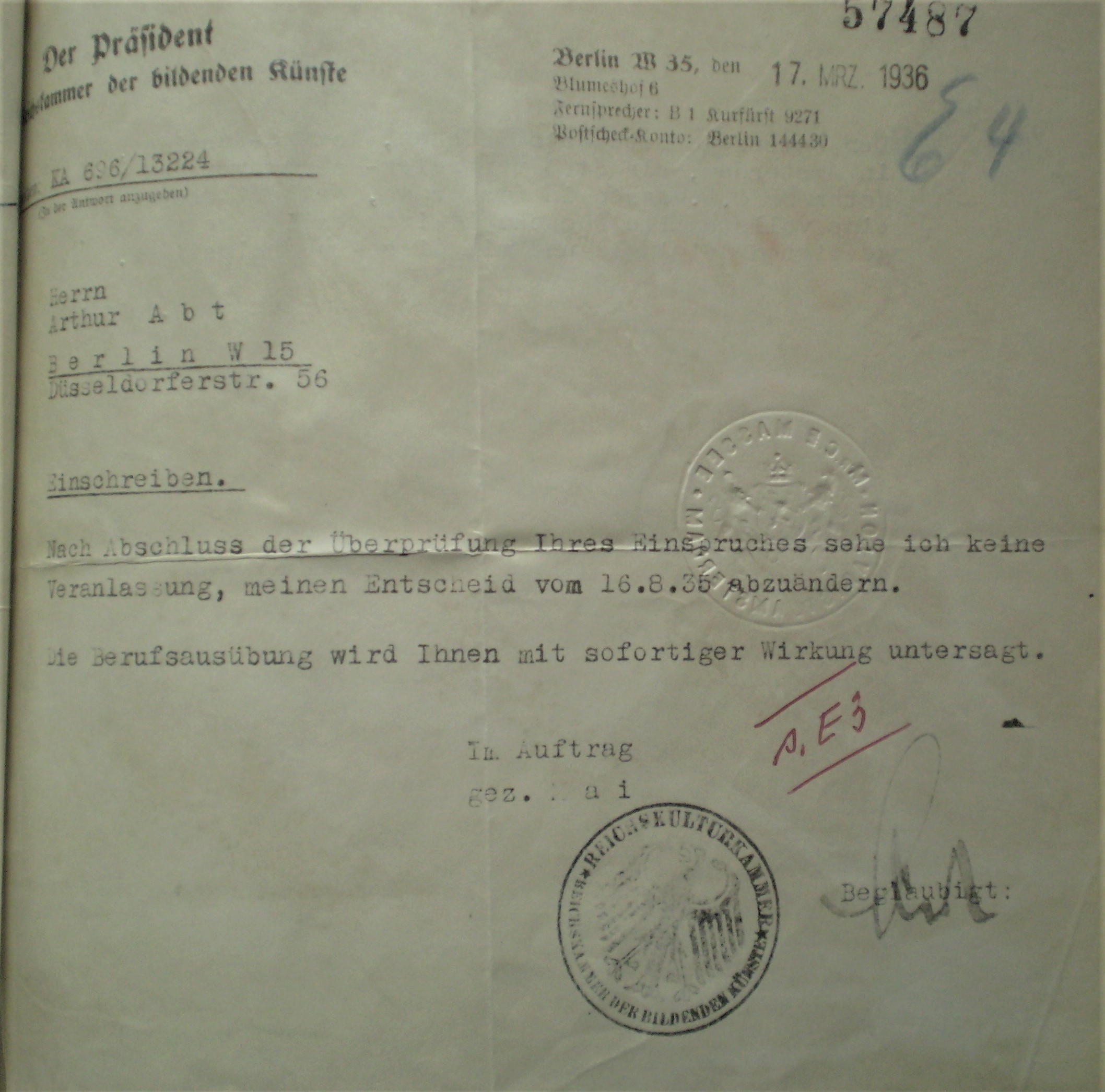

By the late summer of 1935, a wave of relegations had denied admittance to almost 700 art dealers throughout the Reich, including the setting of an absurdly short time limit for business restructuring (fig. 10). For example, on 11 August 1935 the Berlin art agent Arthur Abt was refused admittance to the Chamber; he was given four weeks to dissolve his business. When he objected, the President of the Reich’s Fine Art Chamber confirmed the refusal on 17 March 1936, stating a “conclusion of the review”.33

Fig. 10: Relegation of 16 August 1935;

Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten, Berlin, EA 57 487 Arthur Abt, E 3.

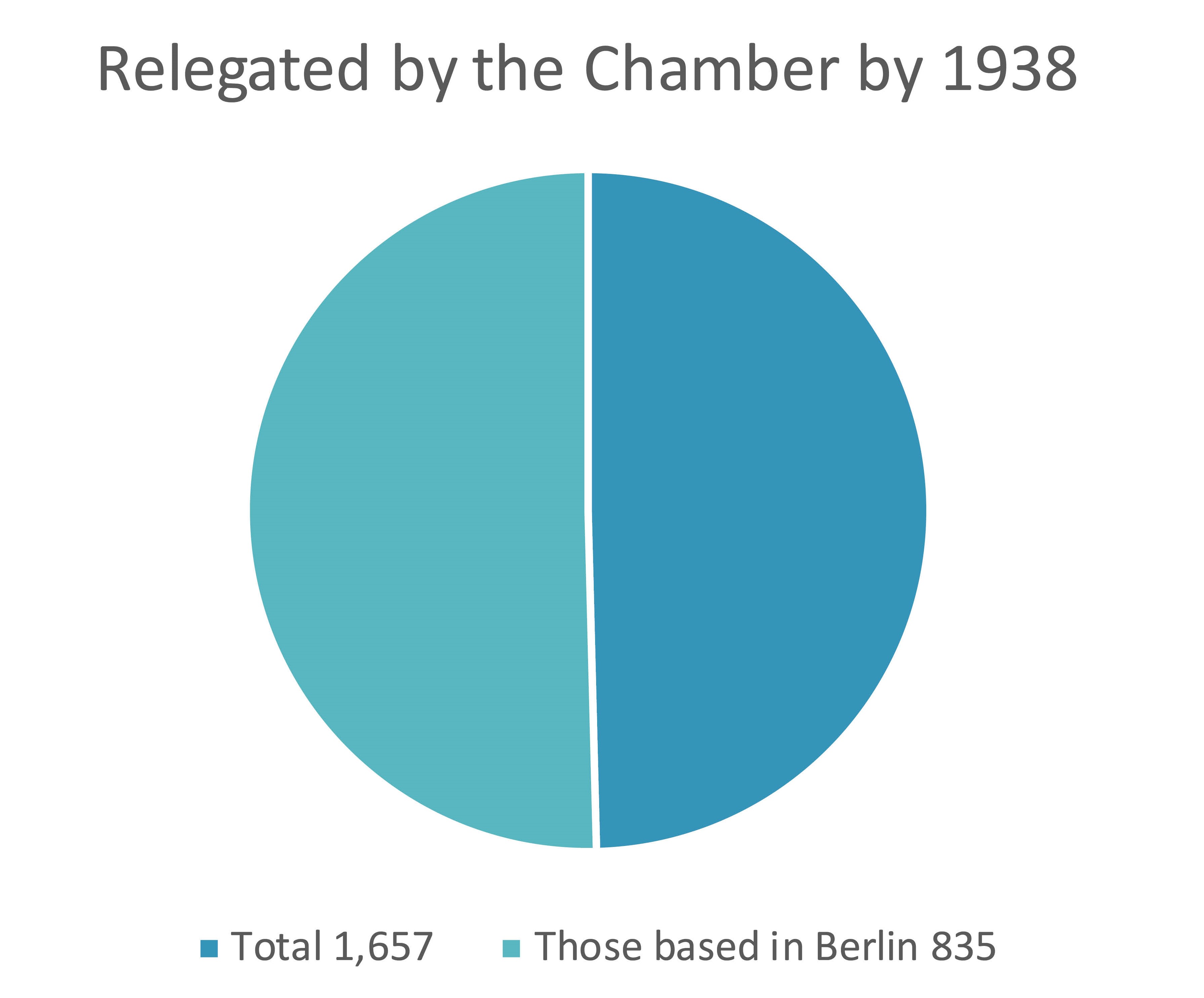

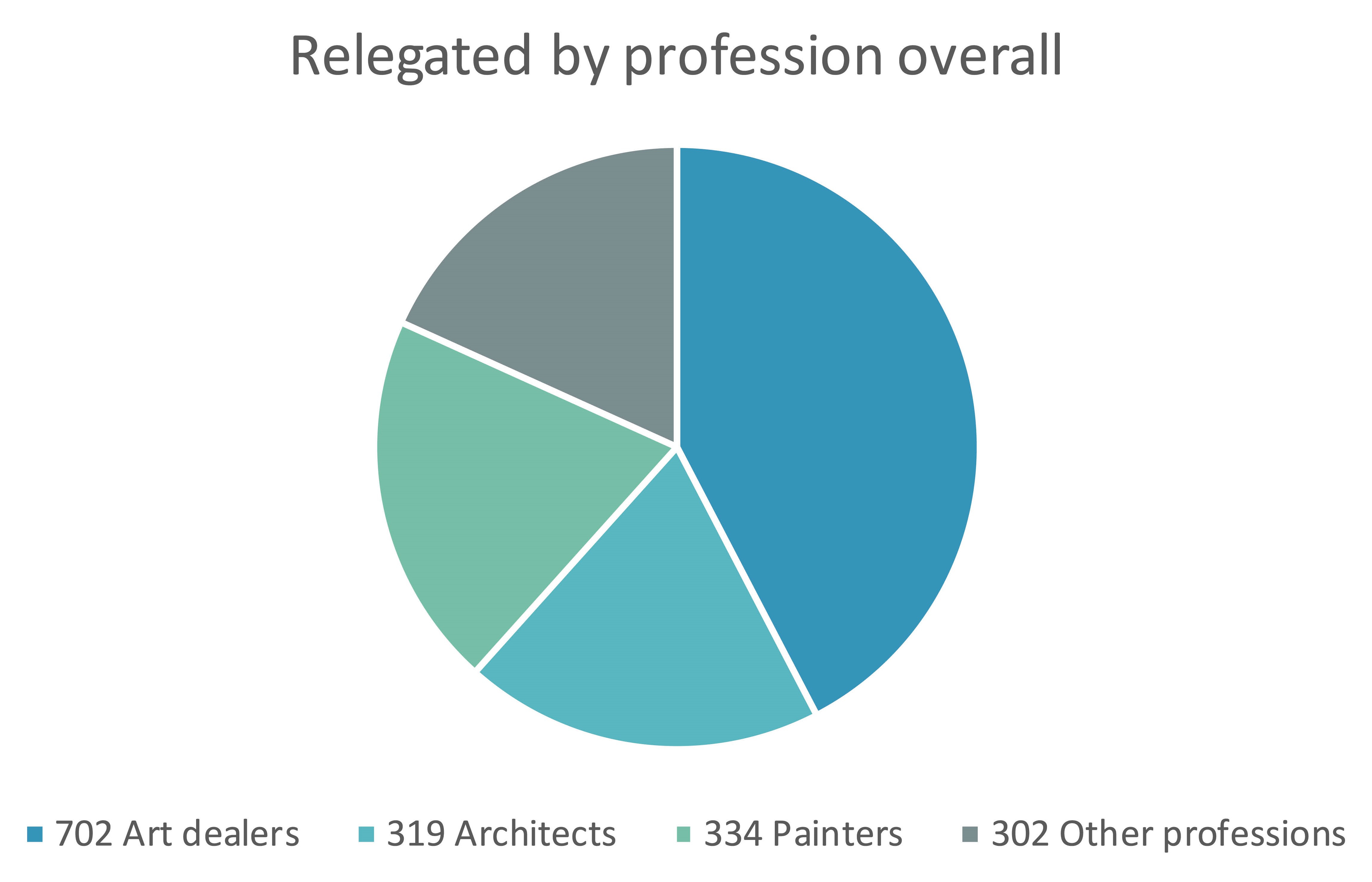

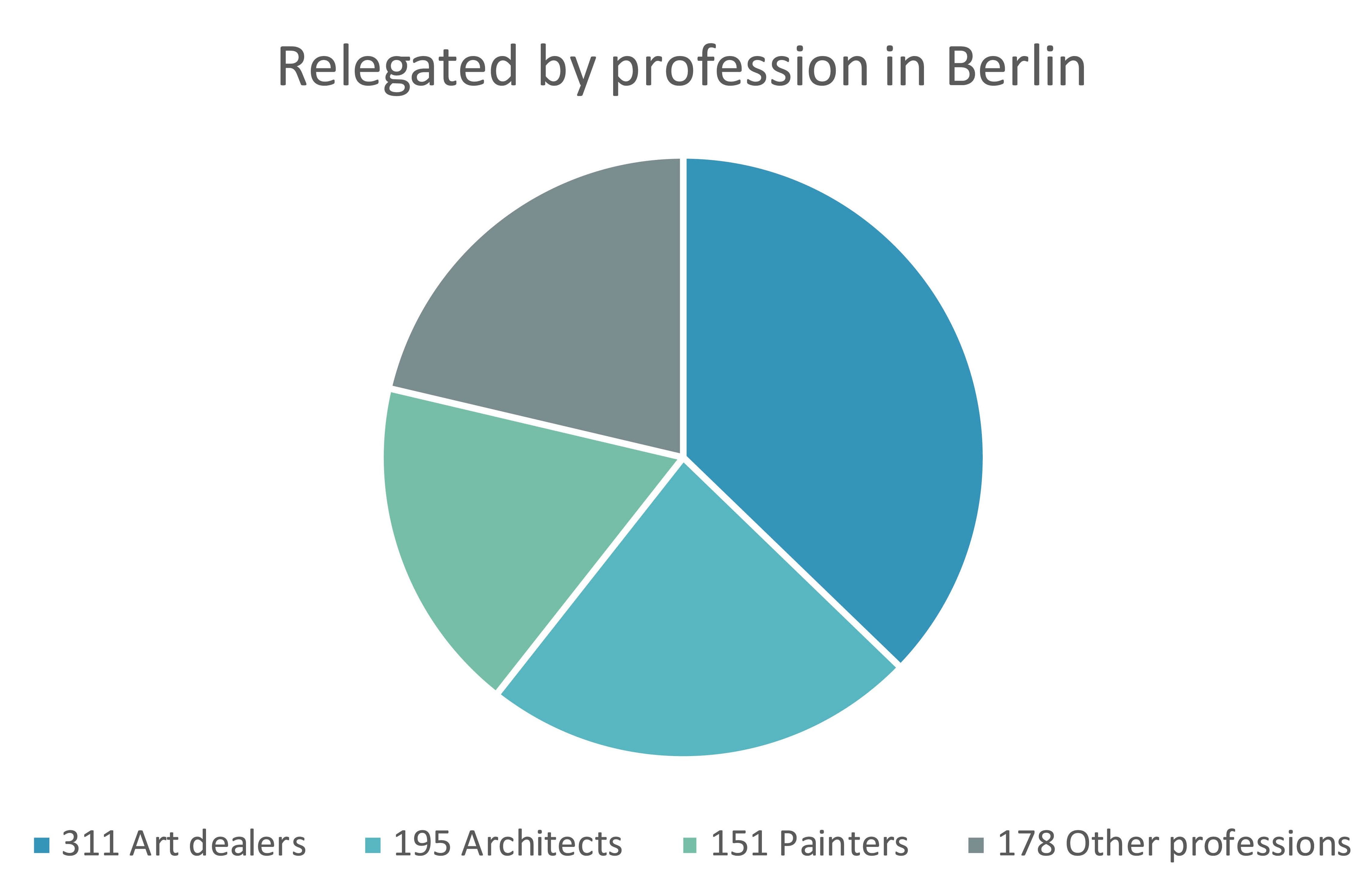

Considering that almost half of 1,657 relegated persons were based in Berlin, one may wonder whether the objective was a “cleansing” of the general cultural sector or rather of the capital (fig. 12).34 A breakdown of relegations by profession shows that more than half were art dealers (fig. 13), indicating a particular eagerness for targeted persecution of the interface of art and money. However, looking at Berlin relegations overall, the percentage of dealers was smaller than in the entire Reich, pointing rather to the importance of the capital as a place of education and training as well as a seat of employers, for example for architects and painters (fig. 14).

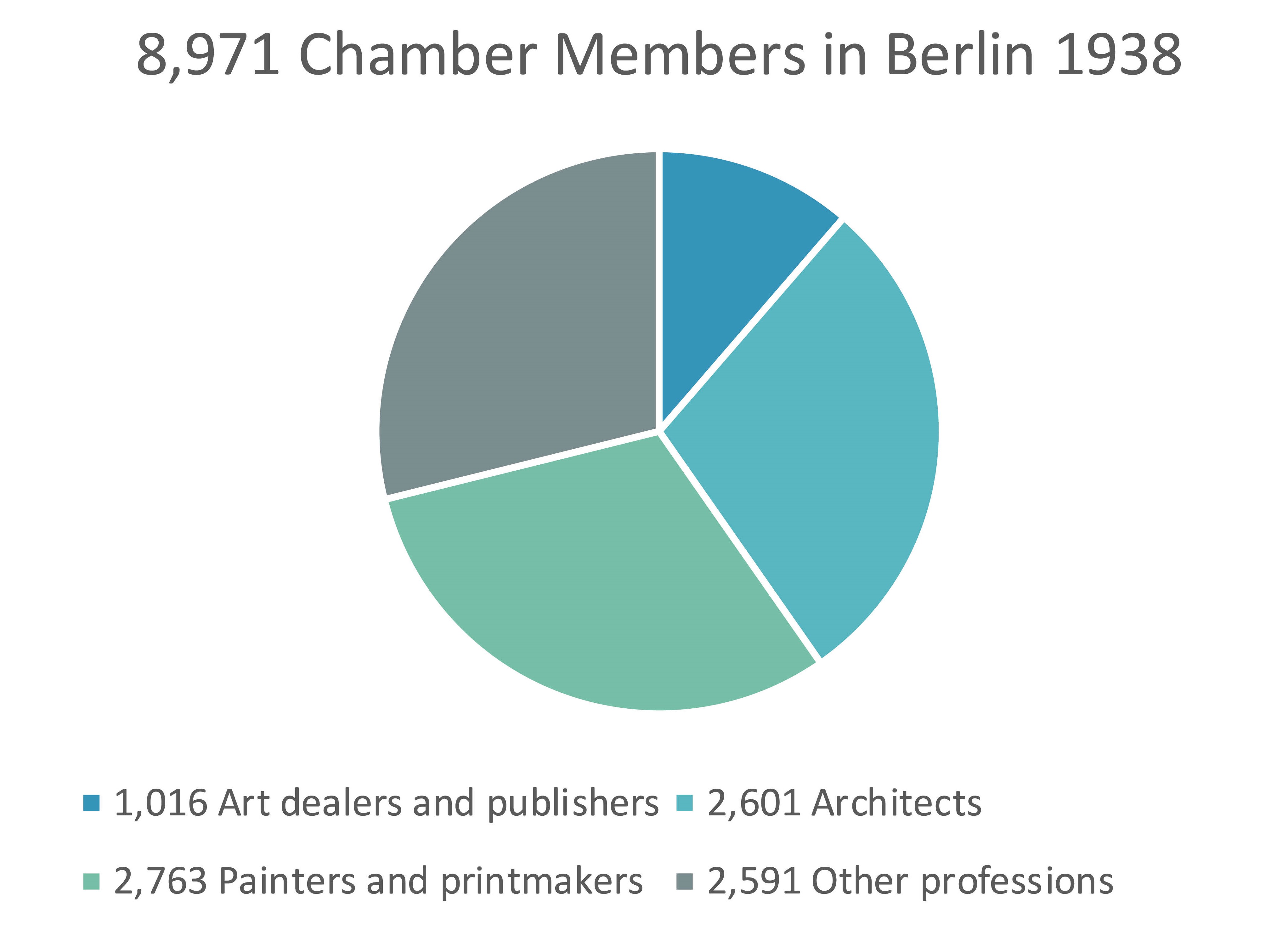

Looking at the distribution of Chamber members in 1938, there is clearly a pressing need for further research in order to clarify whether the same proportion between art dealers and other self-employed professionals in Fine Arts, such as painters, architects and others had existed previously (fig. 15). It is noticeable that the Berlin Chamber management counted “326 refused or relegated [persons], who are constantly monitored” among 1,016 art dealers in its catchment area.35

Nevertheless, the mass relegation effected through licensing did not translate into a clear cut, but rather into an extended process. The system of enforced licensing not only governed market access, but also influenced options to adapt. It caused multiple evasive actions and exit transitions, since it ultimately eliminated all forms of adjustment. Those art dealers who were excluded faced twofold persecution: on the one hand, there was disbarment, which could still be partly negotiated through evasive manoeuvring. On the other hand, they were affected by other forms of persecution, including the dispossession of Jews, which further restricted options for transition and evasion and inevitably led towards emigration or death.

It is however necessary to assess the art trade in the general context of the annihilation of Jewish business activities. At the same time, evaluating the options left open for these dealers – in fact, agency under constraint – would permit a more comprehensive understanding of their decisions and activities and eventually of the historical facts.36

Objections to relegation could only be filed with the same authority, which inevitably led to reconfirmation. However, any objection suspended the terms of delivery for those relegated and increased their time for manoeuvring (fig. 11).37 Economic concerns also prompted the granting of approximately 32 special licenses, issued in readmission processes.38

The most frequent reaction to relegation was downsizing. A dealer would adapt the business profile by moving away from licensed goods towards those outside the license definition – in other words, the art dealer rebranded as a bric-a-brac shop or as a seller of reproduction goods. The Ordnungspolizei, responsible for the maintenance of law and order, found this taxing to deal with, and even if a fine was imposed, it could be temporarily averted by raising objections and petitioning, which would force the decision to be escalated right up to the minister. At the same time, work activities remained vulnerable to observers and informers. 39 In addition, research needs to take into consideration third party adversaries who were in a position to further undermine the business, for example by tenant eviction.

Fig. 11: Confirmation of relegation dated 17 March 1936; Bundesentschädigungsakte, Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten, Berlin, EA 57 487 Arthur Abt, E 4.

Such a strategy required a certain capacity for disobedience or resistance. A dealer of ethnographic objects was able to gain a respite of almost two years through petitions and objections, since the police were unable to evaluate his wares and he kept asking for details of the particular object which was relevant to sentencing. In the meantime, he no longer sold from shop premises, but relied solely on his already established mail order business.40

A move away from shop premises was another form of adaptation, as was the relabelling of goods. One may become a broker, but even then, the definition of goods needed to be considered so as not to fall under the licensing requirement again, and some measure of risk remained.41 The above-mentioned dealer of ethnographic objects eventually rebranded his business as brokering household furniture.

A structural adaptation would change the legal status of the business in order to bypass the license, and to avoid self-employed status, for example by taking on a business partner.42 One model was to form a general partnership between the relegated dealer with a business partner who was based abroad, with the latter holding the license. To deflect attracting further attention by the former’s name the entrepreneurs then converted the business into a public limited company, with the relegated dealer taking a back seat in holding a minority share. However, in the case in point, the Chamber tracked down the information in a follow-up inspection and thus opened the floodgates for the business to be purchased by a direct, non-Berlin-based, competitor.43

Fig. 12: Relegated by the Chamber in 1938: Germany and Berlin; author’s own calculations based on BAB R 55/21305.

Another form of adaptation concerned the dealer’s own manpower, which might not only be transformed into that of an employee, but also be redefined as being “mechanical” and “manual” in character, and thus below the licensing radar. The success of this strategy critically depended on visibility, which would be the first point of vulnerability: a saleswoman in a specialist shop was more likely to attract attention than the stock manager working behind the scene.44

Finally, there was the option of delegation. In this structural adaptation, the entire business was transferred more or less nominally to a license holder. The chances of success increased if the designated licensee was not a new applicant in this context, since the data collected revealed the professional or financial background of the transaction. In one case, while a license was not denied as such, the underlying contracts were not accepted, as the participants were suspected of being front men.45 In such cases, again, third parties could actively intervene, as one delegation which had been accepted for reasons of attracting foreign currency was torpedoed by a denunciation from a direct competitor.46 Both the process and the time limits were influenced by competing institutions. Even a deliberate lack of intervention could be based on expectations of profitable gains, be they material or in the form of vital business intelligence.47

Fig. 13: Relegated by the Chamber in 1938: professions;

author’s own calculations based on BAB R 55/21305.

An alternative reaction was withdrawal. The decision to take this route would depend on the economic position of the relegated dealer and the future options derived from it. Those who considered themselves financially secure, retired from professional life;48 those with alternative chances to work sold;49 those with business connections abroad closed down in order to come away with the name and, if possible, the stock-in-trade.50 Such a decision depended to a large extent on the existence of a competent or even powerful or menacing successor, who may have been further enabled by the backing of an institution.51 The prices agreed or even paid under these constraints do not reflect the actual exchange value. Such processes of sliding and decreasing adaptation continued until the end of 1937 and into the year 1938.

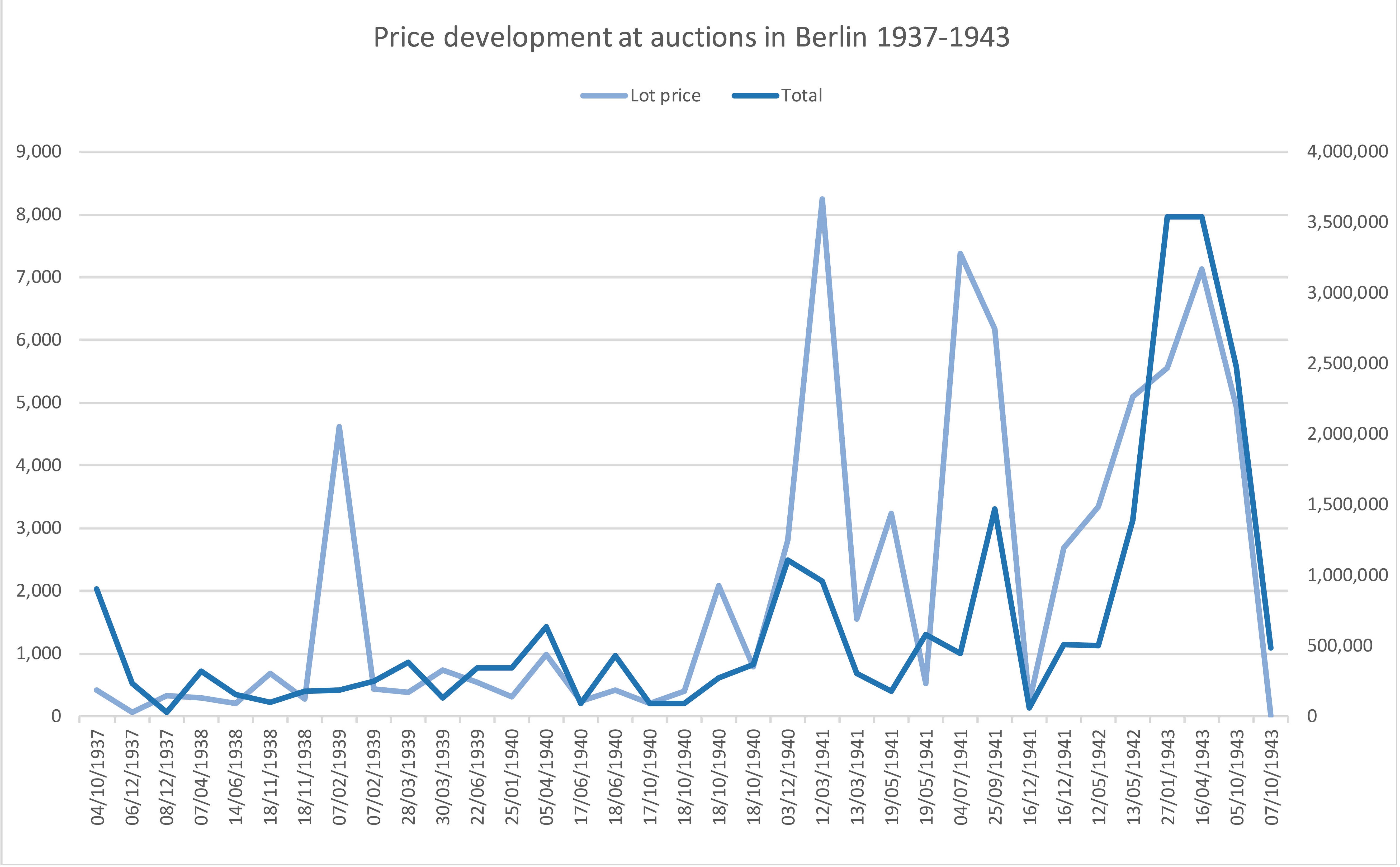

As an intervention of political economics, restricting market access to license holders, as in supporting the Mittelstand, had little effect initially. The purchasing power of those who had been relegated or expelled was removed. This was felt until 1940, as demonstrated by the following chart of sample curves of prices and auction results (fig. 16).52

Fig. 14: Relegated by the Chamber in 1938: Berlin and professions;

author’s own calculations based on BAB R 55/21305.

An analysis of purchases by 14 art commission agents in five Berlin auctions in 1935 shows that they held a share of the total sold proceeds of between 25 and 44 percent. These bidders were usually authorised by the buyer on whose behalf they acted, but now, under the new regulation, they also needed to register their profession. Seven of these agents were relegated in 1935. This was clearly a contested market, which the relegated dealers first dominated and finally lost after a very brief recovery while negotiating their relegation: the size of the prize was at least a quarter of market turnover, which was to be safeguarded for the licensees.53

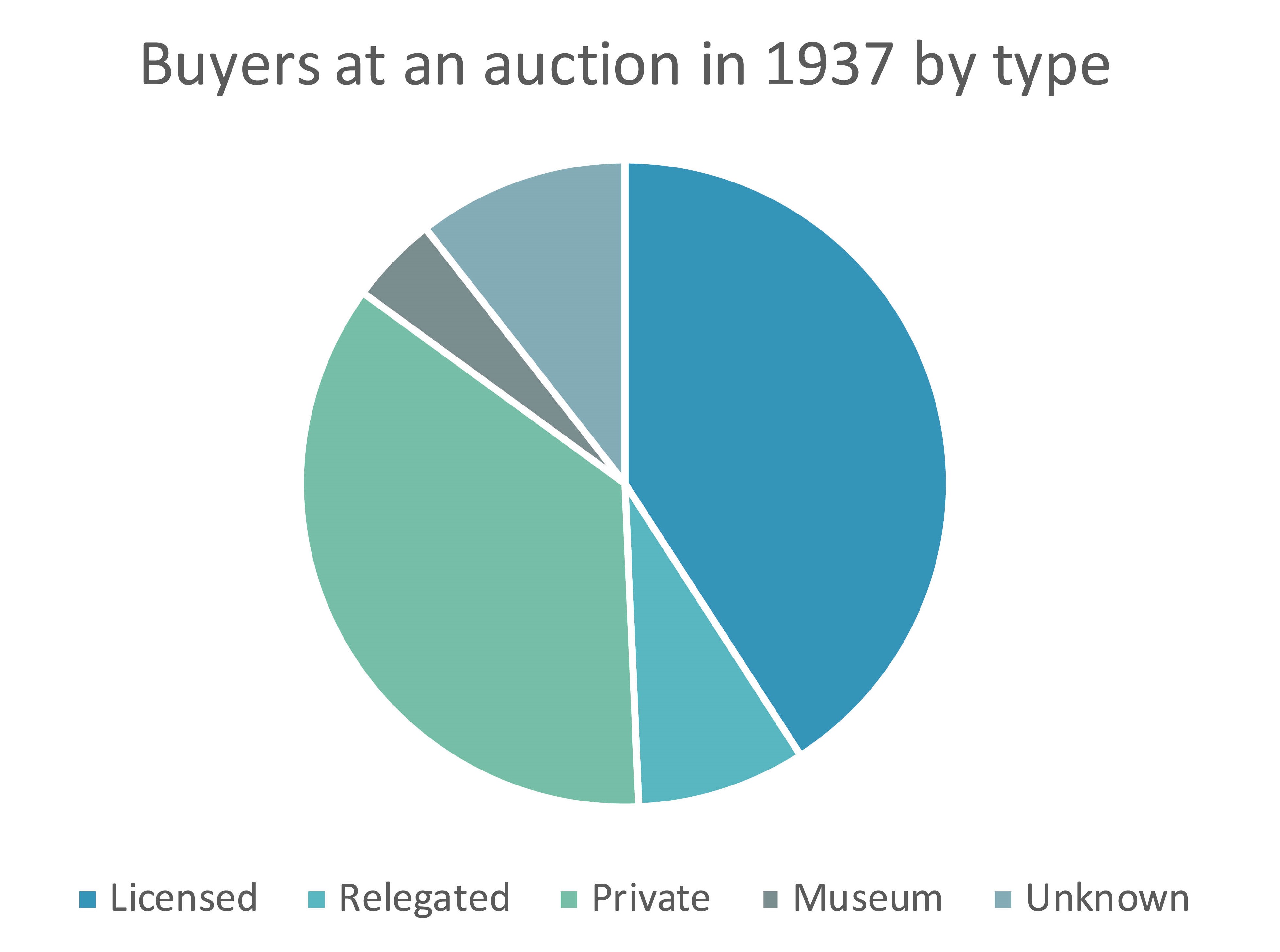

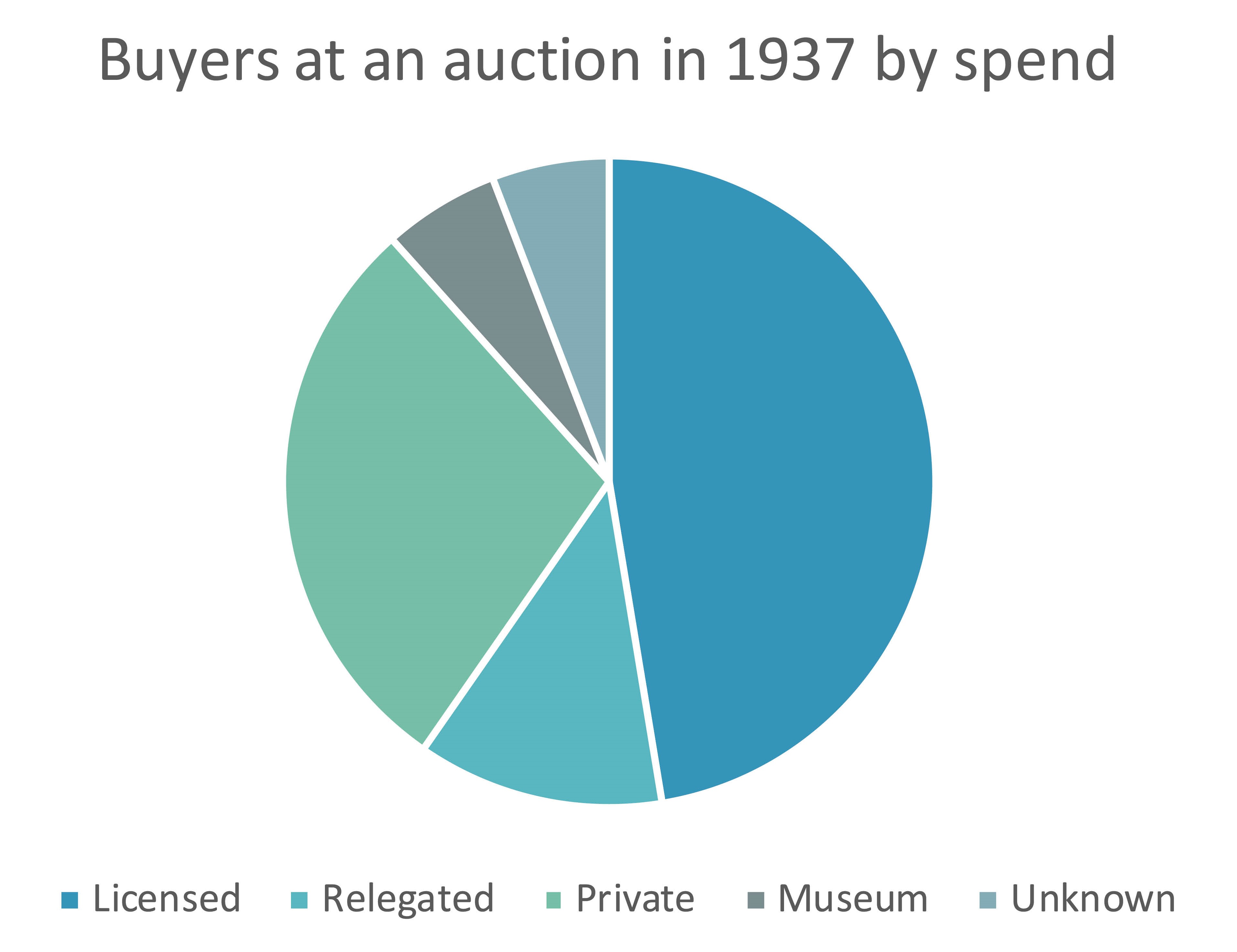

The trade participated in more than half of the purchases at a large Berlin auction sale in the autumn of 1937. Among these, 41 percent of buyers were license holders. With 8 percent relegated, this translated into a much higher percentage in terms of sale value. In this example, more than half of the turnover would have become monopolised by the licensees (figs. 17 and 18).54

Fig. 15: Chamber Members in Berlin 1938 by profession

Author’s own calculations based on LAB A Rep. 243-04, no. 75, 18 March 1938.

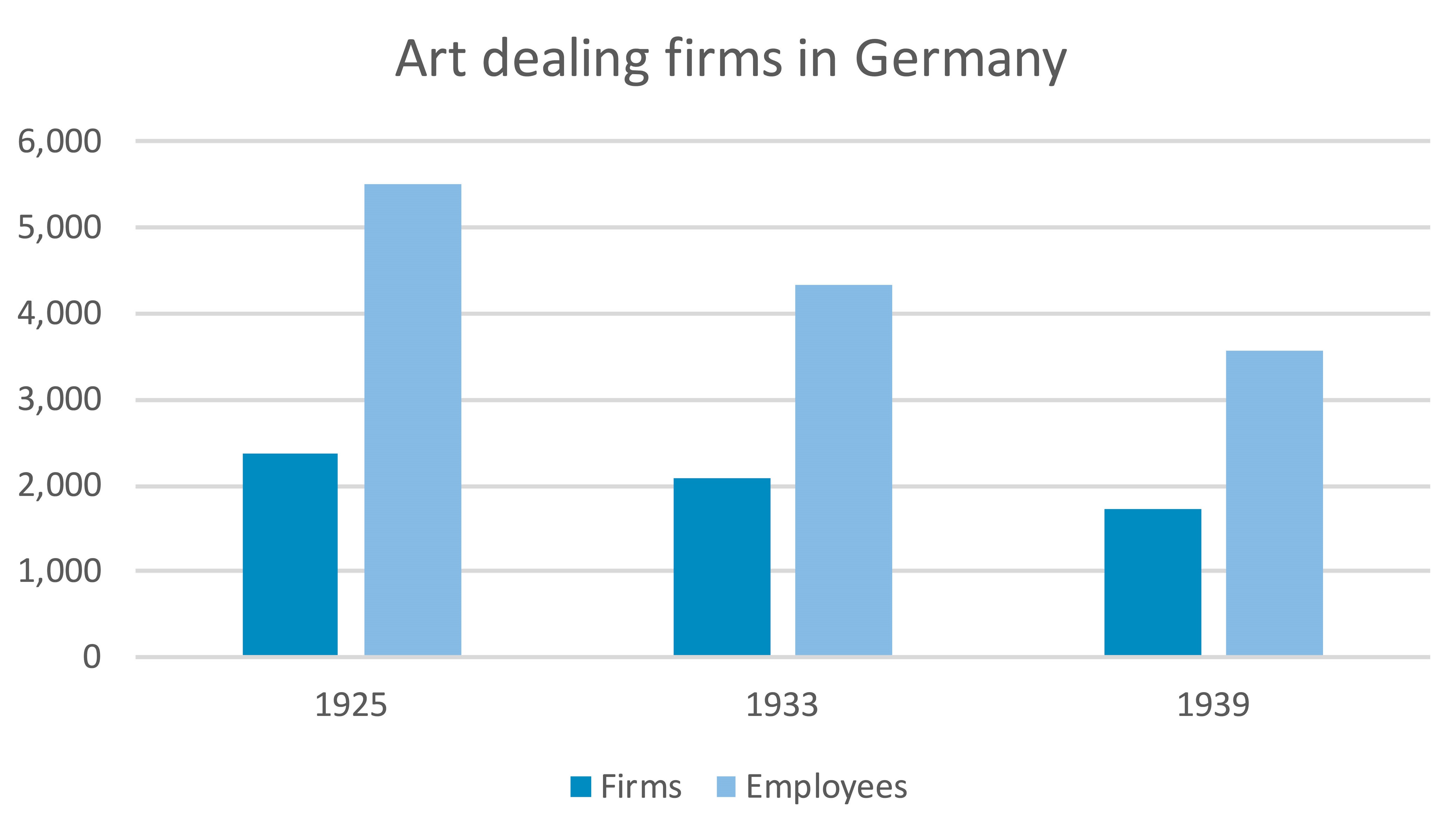

With a business size of two employees on average, the art trade tended to favour family involvement (fig. 19).55 Since the economic downturn of 1930, many of these firms would have to be referred to as “proletaroid” (Theodor Geiger), essentially describing self-employment in order to avoid unemployment.56 They certainly did not dispose of the means to benefit from the wave of relegations and only generated more income during the later increase in prices.57

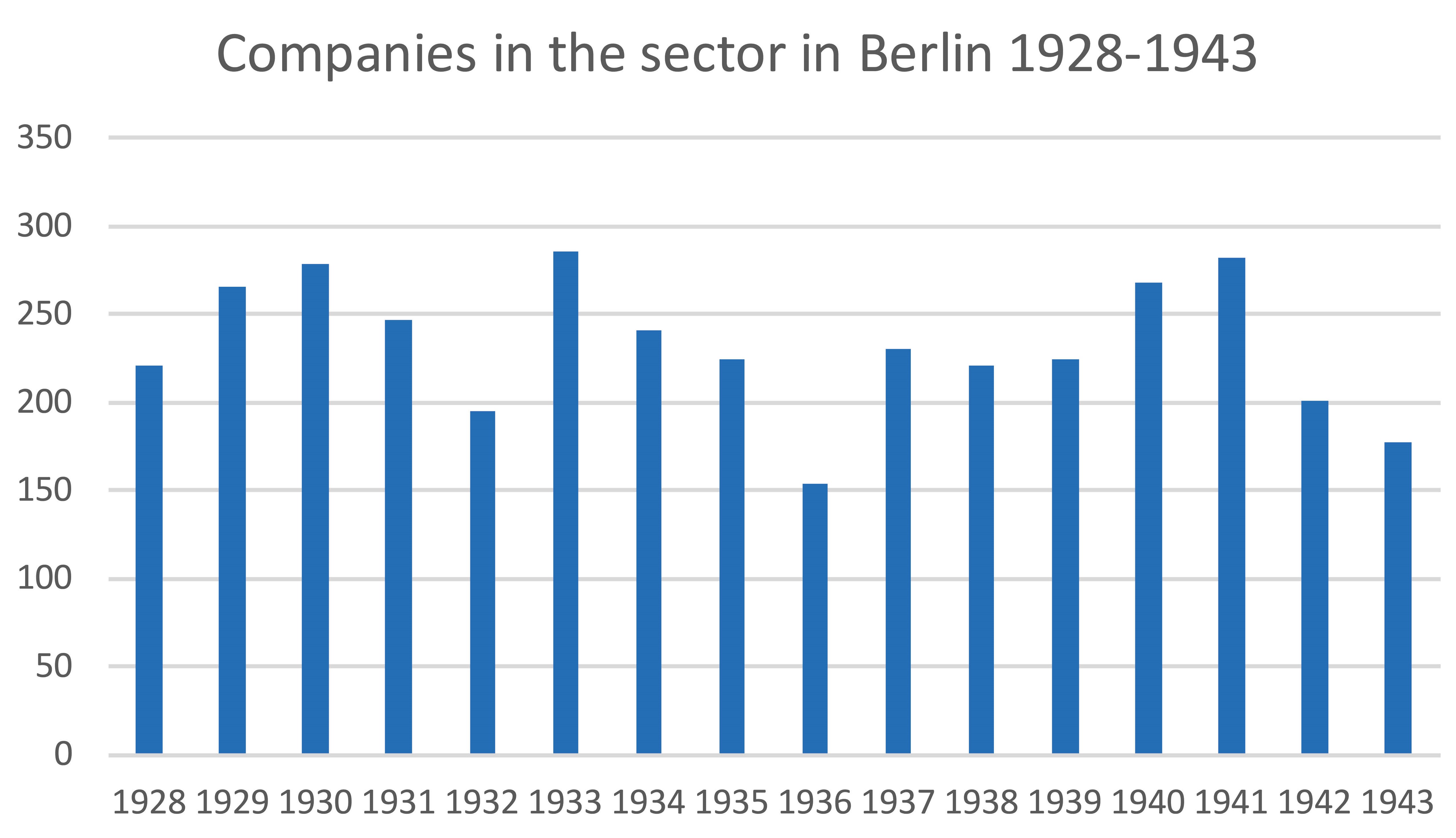

Considering the interventions, the number of enterprises in Berlin from 1928 to 1943 remained surprisingly stable and only fell some time after the beginning of the war (fig. 20).58 While there was a marked dip in 1936, when the number fell by 70, it recovered and even surpassed previous numbers in the following year. According to the research for this article, this would not simply translate into a linear substitution of relegated dealers by licensees. Rather, it demonstrates the shortcomings of the documentary source, since the number of advertisements in the directory of the art trade had already dropped by 52 in times of economic uncertainty from 1931 to 1932, only to rise again in 1933 by 91 (advertising orders received in the previous year). Further research and investigation are needed in this area.

Fig. 16: Price development in the art trade 1937-1943: auction totals and lot prices achieved at the auctioneering firm Hans W. Lange, Berlin; author’s own calculations based on Lange’s publications and Weltkunst magazine.

Licensees benefited from the relegation drive by reduced competition and by upgrades, which does not however present a mirror image of the above-mentioned downsizing strategies. Employees became self-employed with the acquisition of a firm;59 bigger firms bought stock-in-trade and became even bigger;60 beginners were able to acquire their own stock at affordable prices.61

Some new entrants to the trade who had hoped to profit from the redistribution failed because they were unable to keep the acquired business going,62 others demonstrated a flying start in their turnover figures.63

The Chamber seems to have kept skilled employees on standby for takeovers, but these might be rejected by existing business owners and would have to start their own firm;64 others spotted a niche for specialisation and founded successful start-ups.65 As prices slowly began to rise, new businesses kept appearing. These did not necessarily last, but were able to participate in a market with less competition. But the relegated dealers had taken irreplaceable expert knowledge with them, as can be demonstrated by the number of important specialist firms which they were forced to create elsewhere. Once in New York, the above-mentioned bric-a-brac dealer founded an influential gallery for ethnographic art with a reputation that went far beyond its specialist field of trading.

Fig. 17: Buyers at an October 1937 auction in Berlin by type;

Author’s own calculations based on LAB A Rep. 243-04, no. 28.

After the elimination of rights, all licensees were potentially subject to punishment and relegation. As a relegated dealer had been reported to have sported insignia of the “German Workers Front”, the employees of a relegated coin dealer swiftly place an order for membership badges of the Reich’s Fine Art Chambers, which had been designed in 1937 (fig. 21). The “right” political convictions needed to be demonstrated as well as subverted.66

Under perennial threat of penalties and being barred from the profession, let alone ideological convictions and improved profit chances, licensees became loyal operators and suppliers. If they still wanted to sell contemporary art based on their own aesthetic ideals, they were forced to navigate a difficult and dangerous environment.67

If we follow the logical line of thought that a license should be required for handling dangerous goods, it is only natural that the sale of “dangerous” cultural objects was exclusively handed over, bound by an exceptional license, to a limited number (four, in fact) of contracted dealers after 1937.68

Fig. 18: Buyers at an auction in Berlin in October 1937 by spend; author’s own calculations based on LAB A Rep. 243-04, no. 28.

It is equally logical that a dealers’ license to exhibit, which had been immanently included, was gradually retracted. Restraints were first established in Berlin – always a dangerous place, the capital –, and the license to exhibit was eventually rescinded and replaced by a permission relating to specific objects.69 In a complementary move, the control mechanism for “inferior art objects” was set up in the autumn of 1940. It became multifunctional as it could be activated on a case by case basis, permitting intervention at will and regardless of category.70

Fig. 19: Art dealing firms in Germany, 1925, 1933, 1939: Companies and employees; based on Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 51 (1932), 88; 53 (1934), 111; 59 (1941/42), 184.

From a reverse perspective, the temporary measure of marking such “endangered” goods signalled to buyers that they might make an offer, but should not overpay – at the expense of the dealers and sellers.71 Large numbers of objects which had been looted did not enter the art market. At the same time, objects taken from those who were persecuted were readily available for purchase directly from the financial authorities.

Fig. 20: Art dealing companies in Berlin 1928-1943 according to the Yellow Pages; Count of the entire art trade in Berlin 1928-1943 for the exhibition "Gute Geschäfte" 2011, Aktives Museum e.V.

Those contradictory effects were little suited to settle the market. The licensees began to stockpile objects which would only be sold later in a seller’s market with bigger profit margins. Price increases were due to a change in taste, as clients invested profits made in the wartime economy in collections. At the same time, the public found that their expenses on the cost of living and consumer goods decreased by up to a quarter in these leaner times, driving investments in tangible assets such as art.

As demand exceeded supply, pressure grew on emigrated relegated dealers who were still within reach. Especially in the Netherlands, they were under a dual threat.72 Regardless of whether an approach by former colleagues was made to help them generate income, or by adversaries who wanted to blackmail them into selling low, they became virtually part of the new system, forced to use their knowledge to make more objects accessible for the market, or to reintroduce their objects into the market via the licensees.73

Fig. 21 a: Lapel pin of the Reich’s Culture Chamber, design by Richard Klein, 1937; and fig. 21 b: the pin © Süddeutsche Zeitung

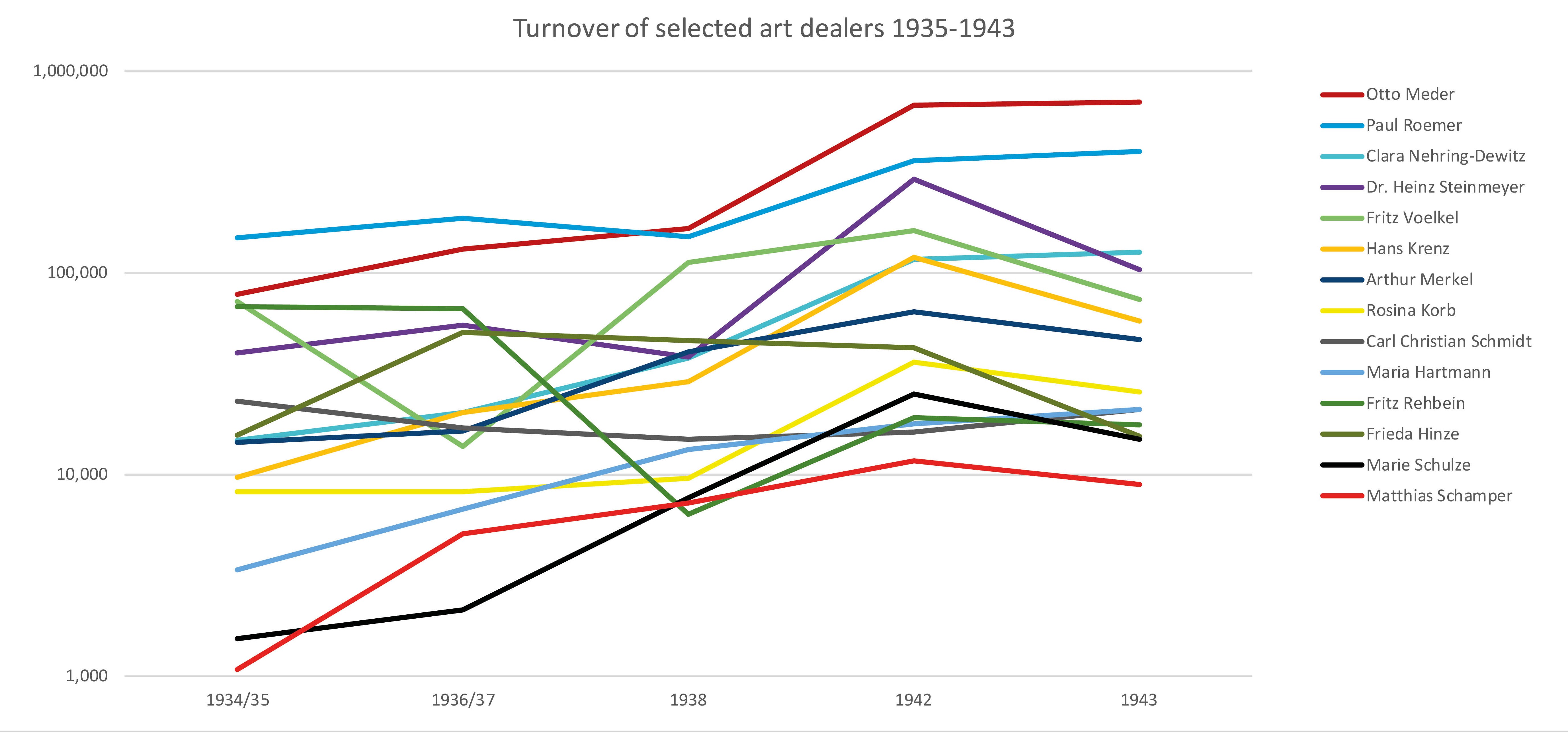

After a drop in prices, the art market began to develop until new peak prices were reached, for no regulation could prevent these. The licensees only reached a comfortable economic position when external factors took hold, such as an artificially high demand in the war economy. These factors ultimately combined to drive a massive increase in turnover across categories for all dealers (fig. 22). The sample shows 14 dealers for whom turnover data were available. The scale shows some smaller antique dealers at the bottom, as well as a dealer in popular or trivial art, who were able to grow up to tenfold. At the top there was a serial prints dealer whose income level created a need for scaling logarithmically in the first place. Such a steep exponential curve was owed to the command of the armed forces, which kept building barracks but could no longer furbish them, leading to a proliferation of prints with nationally uplifting motifs on the walls.74 An opposite fate was that of the dealer and commission agent two curves below, who was conscripted for military service.75

It follows that a secure income for permissible and party-compliant art dealers was not so much the result of relegation, even though it served its own purpose of driving Jewish dealers out of the profession. Yet it had also been intended as a measure to increase the market share of the Mittelstand in the industry. Instead, a growth in income only materialised through a cumulative effect of selection, accelerated demand and lack of investment choices in the war economy. It was only this aggregate effect that would provide even the smallest firms with a secure income, as the late entries in the mid-1935 lists demonstrate.

Fig. 22: Turnover development of selected art dealers 1935-1943: Increases according to their own submissions to the Chamber for calculating their contribution payments; author’s own calculations based on archived personal files.

With regard to economic policy favouring the Mittelstand, licensing hardly turned out to be fit for purpose, and even less so with regard to trade control. As a categorical means of the “national appropriation” of art, its effect was almost paradoxical, since it actually started and accelerated an international distribution of art objects.

Translation: Susanne Meyer-Abich

Caroline Flick is an independent researcher based in Berlin, working and publishing on the history of the auction house Hans W. Lange and the art trade in the National Socialist era.

1 I would like to express my thanks to the editor of the Journal for Art Market Studies, Susanne Meyer-Abich, for helpful comments, fruitful discussions and intelligent translation, and to the Journal’s anonymous reader of the article. The article is based on a paper presented at the 2016 workshop on “Politics and the Art Market” organised by the Centre for Art Market Studies at the Institute for Art History and Historical Urban Studies at Technische Universität in Berlin.

2 Landesarchiv Berlin [LAB] A Rep. 243-04 no. 70, unnumbered; see also two additional postscripts with few names dating from 5 December 1935 and 10 February 1936.

3 For an initial description and analysis of the documentation see Anja Heuß, Die Reichskulturkammer und die Steuerung des Kunsthandels im Dritten Reich, in Sediment 3 (1998), 49-61; on the art trade see Angelika Enderlein, Der Berliner Kunsthandel in der Weimarer Republik und im NS-Staat. Zum Schicksal der Sammlung Robert Graetz (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2006); Gute Geschäfte. Kunsthandel in Berlin 1933-1945 (Berlin: Aktives Museum Faschismus und Widerstand in Berlin, 2011); Meike Hopp, Kunsthandel im Nationalsozialismus. Adolf Weinmüller in München und Wien (Köln-Weimar-Wien: Böhlau, 2012); Anja Tiedemann, ed., Die Kammer schreibt schon wieder. Das Reglement für den Handel mit moderner Kunst im Nationalsozialismus (Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, 2016); Uwe Fleckner/Thomas Gaethgens/Christian Huemer, eds., Markt und Macht. Der Kunsthandel im “Dritten Reich” (Berlin-Boston: De Gruyter, 2017).

4 Nina Kubowitsch, Die Reichskammer der bildenden Künste. Grenzsetzungen in der künstlerischen Freiheit, in Wolfgang Ruppert, ed., Künstler im Nationalsozialismus. Die “deutsche Kunst”, die Kunstpolitik und die Berliner Kunsthochschule (Köln-Weimar-Wien: Böhlau, 2015), 75–96; Caroline Flick, Struktur, Besetzung, Alltag. Die Berliner Landesleitung der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, in Tiedemann, ed., Die Kammer schreibt, 19-48.

5 Zur Reichskulturkammer siehe Volker Dahm, Anfänge und Ideologie der Reichskulturkammer, in Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 34 (1986), 53-84, http://www.ifz-muenchen.de/heftarchiv/1986_1_2_dahm.pdf (251018); Alan E. Steinweis, Art, Ideology and Economics in Nazi Germany. The Reich Chambers of Music, Theater and the Visual Arts (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993); Volker Dahm, Nationale Einheit und partikulare Vielfalt. Zur Frage der kulturpolitischen Gleichschaltung, in Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 43 (1995), 221-266, http://www.ifz-muenchen.de/heftarchiv/1995_2.pdf (251018); Uwe Julius Faustmann, Die Reichskulturkammer. Aufbau, Funktion und rechtliche Grundlagen einer Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts im nationalsozialistischen Regime (Dissertation, Universität Bonn) (Aachen: Shaker, 1995).

6 See in this context research on individual Chambers and their sub-sections: Michael Nungesser, “Als die SA in den Saal marschierte ...”. Das Ende des Reichsverbandes bildender Künstler Deutschlands (Berlin: Bildungswerk d. BBK Berlin, 1983); Jan-Pieter Barbian, Literaturpolitik im “Dritten Reich”. Institutionen, Kompetenzen, Betätigungsfelder, revised edition (München: Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, 1995); Sabine Klotz, Fritz Landauer (1883-1968). Leben und Werk eines jüdischen Architekten (Berlin: Reimer, 2001); Bärbel Schrader, “Jederzeit widerruflich”. Die Reichskulturkammer und die Sondergenehmigungen in Theater und Film des NS-Staates (Berlin: Metropol, 2008); Anke Blümm, “Entartete Baukunst”? Zum Umgang mit dem Neuen Bauen 1933-1945 (Paderborn: Fink, 2013).

7 For the terminology, see: Erste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Reichskulturkammergesetzes. Vom 1. November 1933, in Reichsgesetzblatt. Edited by the Reichsministerium des Innern [RGBl], Teil I, 1922–1945, 1993 I 797-800, http://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/alex? aid=dra&datum=1933&page=922&size=45 (181018); and also recently: Sebastian Spitra, Recht und Metapher. Die “treuhänderische” Verwaltung von “Kulturgut” mit NS-Provenienz, in Olivia Kaiser/Christina Köstner-Pemsel/Markus Stumpf, eds., Treuhänderische Übernahme und Verwahrung. Interdisziplinär und international betrachtet (Göttingen: Vienna University Press, 2018), 55-70, https://www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com/downloads/openAccess/OA_978-3-8471-0783-5.pdf (181018); for the period, see: Erste Anordnung des Präsidenten der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste betr. den Schutz des Berufes und die Berufsausübung der Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler [Berufsschutzanordnung]. Vom 4. August 1934, in Schriftenreihe der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, Der Präsident der R.d.b.K., ed., no. 1 (1934), 46-48; Mitteilungsblatt der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste [RkbK] mit den Gesetzen und Verordnungen, den amtlichen Anordnungen und Bekanntmachungen der Reichskulturkammer und der Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, Berlin 1 (1936) – 9 (1944), 1 (1936), no. 2, 14 and 2 (1937), no. 7, 16. – Karl-Friedrich Schrieber, Die Reichskulturkammer. Organisation und Ziele der deutschen Kulturpolitik (Berlin: Junker & Dünnhaupt, 1934); Karl-Friedrich Schrieber, ed., Das Recht der Reichskulturkammer. Sammlung der für den Kulturstand geltenden Gesetze und Verordnungen, der amtlichen Anordnungen und Bekanntmachungen der Reichskulturkammer und ihrer Einzelkammern, Vols. 1-5 (Berlin: Junker & Dünnhaupt, 1935-1936); Karl-Friedrich Schrieber/Alfred Metten/Herbert Collatz, Das Recht der Reichskulturkammer. Sammlung der für den Kulturstand geltenden Gesetze und Verordnungen, der amtlichen Anordnungen und Bekanntmachungen der Reichskulturkammer und ihrer Einzelkammern (Guttentagsche Sammlung Deutscher Reichsgesetze 225), part 1-2 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1943).

8 For references see especially: Johannes Conrad, ed., Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, 3rd revised edition, vol. 1-8 (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1909-1911); Paul Herre with Kurt Jagow, eds., Politisches Handwörterbuch, vol. 1.2. (Leipzig: K.F. Köhler, 1923); Joseph Brix and Hugo Lindemann, eds., Handwörterbuch der Kommunalwissenschaften, vol. 1-4 and additional vols. 1.2. (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1918-1927); Ludwig Elster, ed., Wörterbuch der Volkswirtschaft, vol. 1-3, 4., completely revised edition (Jena: Gustav Fischer, 1931-1933); Julius Bachem, ed., Staatslexikon. Im Auftrag der Görres-Gesellschaft, 3rd revised [= 4.] edition, vol. 1-5 (Freiburg: Herder, 1909-1912).

9 For the programme of objectives, see Heinrich Niklisch, ed., Handwörterbuch der Betriebswirtschaft, vol. 1.2. (Stuttgart: C.E. Poeschel, 1938-1939), re Chamber, vol. 2, 518-526 (Georg von Kietzell); re market and regulation, 910-926 (Karl Oberparleiter) and 939-951 (Fritz Wilhelm Hardach); also re direction of the economy “Wirtschaftslenkung (Wirtschaft und Judentum)”, vol. 3 (supplements), 2706 f. (Kurt Uckerl); Heinz Abel, Die Industrie- und Handelskammern im nationalsozialistischen Staate (Dissertation, Universität Breslau, Würzburg: Richard Mayr, 1940) https://archive.org/details/Abel-Heinz-Die-Industrie-und-Handelskammern-im-nationalsozialistischen-Staate/page/n0 (201018).

10 Reichskulturkammer (printed typescript) n.p., n.d. (15 April 1935); Reichskulturkammer (printed typescript) [on the cover: “Die Organisation der Reichskulturkammer”] n.p., n.d. (15 April 1936). – Flick, Struktur, Besetzung, Alltag, 21-27.

11 Reichskulturkammergesetz. Vom 22. September 1933, RGBl 1933 I 661 f. http://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/alex? aid=dra&datum=1933&page=786&size=45 (181018); see Zweite Verordnung zur Durchführung des Reichskulturkammergesetzes. Vom 9. November 1933, RGBl 1933 I 969, http://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/alex?aid=dra&datum=1933&page=1094&size=45 (181018). According to this, the First Order will apply from 15 November 1933, with the proviso that the Chambers must be integrated by 15 December in accordance with paragraph 4 of the Order, which will be the prerequisite for professional practice henceforth. See also Berufsschutzanordnung, paragraph 3; and Weltkunst no. 4 (1930) – 18 (1944) (Berlin: Weltkunst-Verlag, 1930-1944), 12 August 1934, 3.

12 Egon Tuchtfeldt, Gewerbefreiheit, in Erwin Beckerath, ed., Handwörterbuch der Sozialwissenschaften. Zugleich Neuauflage des Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, vol. 1-12, Register (Stuttgart-Tübingen-Göttingen: Gustav Fischer-Mohr-Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1956-1965), 4 (1965), 502-507.

13 See Die neue allgemeine Gewerbe-Ordnung für die preußische Monarchie. Vom 17. Januar 1845, in Polytechnisches Journal 95 (1845), 393–413, http://dingler.culture.hu-berlin.de/article/pj095/mi095102_1 (191018), §§ 15, 26, 48; Gewerbeordnung für den Norddeutschen Bund. Vom 21. Juni 1869, Bundesgesetzblatt des Norddeutschen Bundes 1869, no. 26, 245-282, https://de.wikisource.org/wiki/Gewerbeordnung_f%C3%BCr_den_Norddeutschen_Bund (191018), §§ 30 ff., 43, 57; Gewerbeordnung für das Deutsche Reich. Vom 1. Juli 1883, RGBl 1883 177-240, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Deutsches_Reichsgesetzblatt_1883_015_177.jpg (191018) ff., paragraphs 30 ff., 51, 53.

14 Erste Verordnung zur Durchführung des Reichskulturkammergesetzes, paragraph 10; see Berufsschutzanordnung, paragraph 4, nos. 1-5.

15 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 7631 Fritz (Karl Friedrich) Seiler; no. 7084 Curt Reinheldt, see also Bundesarchiv Berlin [BAB] R 9361 V 1847, LAB A Rep. 358-02 no. 650 and no. 98225, LAB A Rep. 092 no. 397, LAB C Rep. 031-03-11 no. 2402 and Staatsarchiv Landshut, Spruchkammer Viechtach, Rep. 241/19 no. 2135. – In order to remain within the scope of this article, only general examples for structures and typology are listed without reference to possible further significant elements in each file; also, multiple mentions are possible.

16 Andreas Sternweiler, Liebe, Forschung, Lehre: Der Kunsthistoriker Christian Adolf Isermeyer (Berlin: Rosa Winkel, 1998); LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 4701 Hans [sic] Krenz, no legal proceedings are mentioned in his personal file, no record could be found in the public prosecutor’s office; BAB R 9361 V 38009 Hermann Tölke, see also LAB A Rep. 358-02 no. 50790 and no. 63698 f.

17 Initially refused: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 393 Alfred Basse; no. 1524 Gerhard Dietze; no. 2611 Robert Gohlke; no. 3676 Wilhelm Honeck; no. 5943 Viktor Modrzejewski; see the range of outcomes from the professional examination (passed/failed/considered as passed due to long-term professional experience/examination required): LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2779 Georg Grothe; no. 2939 Werner van Haersolte; no. 6029 Amalie Mühlfeld; no. 5684 Kasimir Mastai; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5683 Eugen Mastai; no. 73300 Gertrud Stoldt; no. 2284 Lotte Fröhlich; no. 2351 Franz Gaisser; no. 5547 Frieda Mahler.

18 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5, circular no. 77 of the president of the Reich’s Chamber for Fine Arts (RkbK), dated 31 October 1935 and no. 91 of 5 December 1935.

19 Author’s own statistics, based on: Internationales Adressbuch des Altkunst- und Antiquitätenhandels. Hrsg. unter Mitwirkung von Fachverbänden des In- und Auslandes (Weimar: Straubing & Müller, 1933), with a preface dated late September 1932.

20 Dresslers Kunsthandbuch. Auf Grund amtl. Materials bearb. und hrsg. von Willy Oskar Dressler, T. 1, Bildende, redende und spielende Kunst. Das Buch der öffentlichen Kunstpflege (Halle/Saale-Berlin: Buchhandlung des Waisenhauses 8 (1923) – 10 (1934)), 10 (1934)), 671; Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich. Hrsg. vom Statistischen Reichsamt (Berlin 1 (1880) – 59 (1941/42)), 53 (1934)), 111.

21 See the summons in Weltkunst on 24 December 1933, 3: “Aufforderung! Wir erlassen nun unter Berufung auf obiges Gesetz an alle Kunsthändler und Angestellte im obigen Sinne, soweit sie nicht auf Grund ihrer Mitgliedschaft zu dem ehemaligen ‘Reichsverband Deutscher Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler e.V., München’ und dem ‘Deutscher Reichsverband des Kunsthandels e.V., Berlin’ Mitglieder der Fachschaft ‘Bund Deutscher Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler, Sitz München’, geworden sind, die Aufforderung, unverzüglich ein Aufnahmegesuch an die Reichskammer der bildenden Künste, Fachschaft: ‘Bund Deutscher Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler, München, Max-Josefstr.7’, einzureichen, wenn sie nicht des Rechts, mit Kunst und Kulturgut Handel zu treiben, verlustig gehen wollen. Der 1. Vorsitzende: Adolph [sic] Weinmüller.”

22 Staatsarchiv München, Polizeidirektion München 4670, unnumbered, Zentralkomitee zur Abwehr der jüdischen Greuel- und Boykotthetze, München, Dr. Doll, an das Reichswirtschaftsministerium, Berlin, dated 21 July 1933; see Reichswirtschaftminister, Berlin, Dr. Josten, to Geheime Staatspolizei, Bayerisches Ministerium des Innern, München, dated 21 August 1933. See also Weltkunst 16 July 1933, 4; 23 July 1933, 4; and Meike Hopp, Der Kunsthändler Adolf Weinmüller (München/Wien) und seine Rolle bei der einheitlichen Neuregelung des Deutschen Kunsthandels, in Eva Blimlinger and Monika Mayer, eds., Kunst sammeln, Kunst handeln. Beiträge des internationalen Symposiums in Wien (Wien-Köln-Weimar: Böhlau, 2012), 65-77; Hopp, Kunsthandel im Nationalsozialismus.

23 Author’s own compilation, based on contemporary art magazines: 1911 Deutsche Kunsthändler-Gilde e.V. Hamburg (1919 Arnold Spieckermann); 1917 Verband des deutschen Kunst- und Antiquitätenhandels e.V. München (1933 Siegfried Drey); 1919 Antiquitäten- und Kunsthändlerverband Sachsen e.V. Dresden (1933 Eugen Salomon; Juli Jakob Spiehl); n.d. Frankfurter Antiquitätenhändlerverband e.V. (1932 Otto Müller); n.d. Kölner Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändlerverband e.V. (1932 Alfred Feit); n.d. Vereinigung der Antiquitätenhändler in München e.V. (1933 Otto Striegel); 1927 Interessenverband Groß-Berliner Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler (Ernst Fritzsche); 1928 Reichsverein Deutscher Kunstverleger und Kunsthändler e.V. Berlin (Ernst Schultze); 1929 Verband der Kommissionäre im Kunsthandel Berlin (Martin Schwersenz); 1933, Juli: Fachgruppe Kunst und Antiquitäten im Kölner Einzel-Handel-Verband e.V. (H.C. Dick); 1933, Juli: Reichsverband des Deutschen Kunst- und Antiquitätenhandels e.V. München (Adolf Weinmüller); 1933, August: Arbeits-/Kampfgemeinschaft national-sozialistischer Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler Deutschlands (Ferdinand Wendl); 1933, Oktober: Deutscher Reichsverband des Kunsthandels e.V. Berlin (Walther Fritzsche); 1933, November: Deutscher Reichsverband des Kunst- und Antiquitätenhandels (Adolf Weinmüller/Walther Fritzsche/Hans Sauermann); 1933, Dezember: Bund Deutscher Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler e.V. München [BDKA] (Adolf Weinmüller); Weltkunst, 1 October 1933, 4; see 15 October 1933, 4 f.

24 See Staatsarchiv München, Polizeidirektion München 4670, undated statute of the BDKA.

25 Fragments regarding participation in an Admissions Committee in LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 421 Dr. Theodor Bauer.

26 The earliest form found to date, an application sent to the BDKA while it was still based in Munich, states before the signature: “Die Mitgliedschaft zur Reichskammer der bildenden Künste nach dem Reichskulturkammergesetz vom 1. Nov. 1933 ist nur durch Beitritt zum Bund der Deutschen Kunst- und Antiquitätenhändler möglich und für fernere Berufs-Ausübungen unerläßlich”. See also Weltkunst, 7 January 1934, 3, Notice from the BDKA regarding the questionnaire, and Weltkunst, 29 April 1934, 2, about the obligation to register by 1 May.

27 See for example LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 1524 Gerhard Dietze, first 6 September 1934, then 27 March 1935; no. 7631 Fritz (Karl Friedrich) Seiler, of 26 November 1934; no. 137 Otto Albrecht, of 28 January 1935; no. 345 Eberhard Barg, of 17 May 1935 (entry stamp).

28 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2617 Arthur Goldschmidt; “718” at the top for his membership number KA 718. See also BAB R 9361 V 100472 Otto Haas, KA 591, with the processing note at the top “JL 27/III” [JL 27/IV ?], to be regarded as control mechanism for the “Mai List”; BAB R 9361 V 104562 Ignatz Regierer, [KA] “703”, a red processing note “X Q”; see also LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6795 Alfred Popper, correspondence later marked with “J 149”, numbering of relegated persons, by March 1937 replacing his membership number “KA 235”.

29 Weltkunst 11 August 1935, 4 as “Amtliche Bekanntmachung” [Official Announcement] of the dissolution of both BDKA and the “Bund” of art publishers; see the standardised covering letter below in fig. 10.

30 BAB R 9361 V 100472 Otto Haas: 31 August 1935, exclusion through the dissolution of the BDKA, undated objection by Haas, 14 September 1935, examination of business size, 25 September 1935, visit of the regional manager Barnim Anders to the company and report to the Chamber’s head office (quote).

31 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2691 Paul Graupe, dated 31 December 1935; the President of the RkbK, Dr. Gaber, with the time limit of 29 February 1936; see Patrick Golenia/Kristina Kratz-Kessemeier/Isabelle le Masne de Chermont, Paul Graupe (1881-1953). Ein Berliner Kunsthändler zwischen Republik, Nationalsozialismus und Exil (Köln-Weimar-Wien: Böhlau, 2016). – While this monographic study illustrates the historical development, the scope of this article does not permit a comprehensive quotation of literature references for individuals.

32 Martin Tarrab-Maslaton, Rechtliche Strukturen der Diskriminierung der Juden im Dritten Reich (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1993).

33 Landesamt für Bürger- und Ordnungsangelegenheiten, Berlin, Office for Compensation [Entschädigungsamt] [LABO EA] 57 487 Arthur Abt, E 3 f.

34 “Mai List”: BAB R 55/21305, unnumbered, President of the RkbK, Mai to the Reichsminister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda, dated 8 June 1938, “Liste sämtlicher bisher aus meiner Kammer ausgeschlossener Juden, jüdischer Mischlinge und mit Juden verheirateter” (fl. 1-62), signed by the deputy manager of the RkbK Erich Mai; with a handwritten note in red on the covering letter “J.L.8” – frequently quoted in the literature as the “Jew List 8” – as well as “1657 Ausschlüsse [exclusions]”. – See Angelika Enderlein, Zum Berliner Kunsthandel im Nationalsozialismus. Maßnahmen der nationalsozialistischen Regierung gegen jüdische Kunsthändler und ihre Auswirkungen auf den Berliner Kunsthandel, in Berlin in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 2007), 169-192; Enderlein, Der Berliner Kunsthandel, 116 f. Enderlein arrives at 1,629 exclusions; the differences are probably due to multiple counts under different professions.

35 No comparable numbers are noted for other professions, calculated on the basis of LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 75, RkbK, Landesleiter Berlin, Lederer to the President of the RkbK, Berlin, dated 18 March 1938 reflecting the figures of 31 January 1938; see LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 85, the same to the Kulturreferent of the Landeskulturwalter, Lucht, dated 22 April 1938, mentioning a total membership number of 9,269 as of 31 January 1938; as well as the warning for potential newcomers dating from mid-1939, which stated that the “Gau Berlin” already disposed of more than 3,000 painters, circa 3,000 architects, more than 2,000 printmakers, approximately 800 sculptors and more than 1,000 art dealers, Mitteilungsblatt der RkbK 4 (1939), H. 7, 15. – See also the database “Jüdische Gewerbebetriebe in Berlin 1930-1945“, https://www2.hu-berlin.de/djgb/www/find (291018), listing 103 firms under the heading “Bücher und Kunst“.

36 The following considerations are mainly based on: Christoph Kreutzmüller, Ausverkauf. Die Vernichtung der jüdischen Gewerbetätigkeit in Berlin 1930-1945 (Berlin: Metropol, 2012); and Benno Nietzel, Handeln und Überleben. Jüdische Unternehmer aus Frankfurt am Main 1924-1964 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2012).

37 LABO EA 57 487 Arthur Abt, E 3 f., exclusion on 16 August 1935 with a time limit of four weeks, confirmed on 17 March 1936 after an (unknown) objection was raised.

38 BAB R 43/11 no. 1238c, fl. 11-15, The Reichs- und Preußische Wirtschaftsminister, Hjalmar Schacht, to the Führer und Reichskanzler, dated 13 February 1936, fl. 16-19 Aufstellung ... auf Grund verschiedener Eingaben der betreffenen [sic] Unternehmen; BAB R 55/21305, unfol., President of the RkbK, Mai, to the President of the Reich Fine Arts Chamber, dated 15 March 1937, attachment 2 (fl. 1-2).

39 See the reports in LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2564 Wilhelm Gloose; no. 7027 Fritz Rehbein; obliged, reports not included: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 134 Georg F.W. Albrecht and BAB R 9361 V 98110; BAB RK G 69 2803 Alfons Roy and BAB PK K 81 1039; declaration of consent: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 203 Fritz Appelt; other opportunistic denunciations, for example: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 3734 Hans Hüner; no. 6204 Clara Nehring-Dewitz. Note also the obligation to check registration: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5738 Günther Mecklenburg; no. 4817 Hans Carl Krüger.

40 Exemplary refractoriness: BAB R 9361 V 99165 Julius Carlebach, with thanks for further details to Beatrix Piezonka, Würzburg.

41 See for example: BAB R 9361 V 104562 Ignatz Regierer and LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 31108 HRA 94881 Moderne Kunst-Gemäldegalerie Ignatz Regierer; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 3752 Hussein Husseinoff; LABO EA 70233 Eugen Weissner.

42 See for exampe the efforts made by Peter Paul Kronthal in opening an auction house in partnership with Konrad Strauss, BAB 3101/13915, unnumbered, dated 4 July 1936 ff., with thanks for an exchange with Sandra Schmidt, Paris.

43 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2706 Willem van der Grient and LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 38900 HRA 77960 Bibliographikon Dr. Hans Wertheim as well as no. 58118 HRB 55524 Bibliographikon Willem van der Grient & Co.

44 See LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6613 Pauline Petershen and no. 4603 Werner Krabo; BAB R 9361 V 104194 Maria Pincoffs and LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 61958 HRB 44449 H.u.P. Kunst- und Ausstattungsgesellschaft mbH.

45 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2351 Franz Gaisser.

46 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5547 Frieda Mahler.

47 See about Erich Rappaport: Zentralarchiv Staatliche Museen, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin, I/MK 16, unnumbered, dated 17 June 1936 ff. and LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 9994 Dr. Waldemar Wruck. See also the recent conference paper by Emanuele Sbardella, Die Vertreibung jüdischer Münzhändler aus Nazideutschland. Beitrag für das 53. Süddeutsche Münzsammlertreffen, 14-16 September 2018, Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, https://youtu.be/kHTOuRZkPy8 (061118).

48 BAB R 9361 V 98589 and BAB R 9361 V 139486 Arthur Biberfeld, in this context see BAB R 9361 V 139486; LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 3619 HRA 45445 and LAB B Rep. 025-03 no. 4888/51 Martin Schwersenz, see also LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 31923 HRA 23279 Richard Mannheimer.

49 BAB R 9361 V 101720 Siegmund Kaznelson.

50 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2617 Arthur Goldschmidt; LABO EA 150364 Alexander Ball and LABO EA 150761 Richard Ball; BAB R 9361 V 100472 Otto Haas and BAB R 9361 V 20648 Otto Siegmund Haas.

51 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 4817 Hans Carl Krüger; no. 2691 Paul Graupe, see in this context LAB A Rep. 342-02 no. 20235 HRA 86635 as well as LABO EA 57493; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2762 Rolph Grosse.

52 Author’s own calculations based on the valuation and sale results published in the specialist art trade magazine Weltkunst for the firm as well as valuation and result lists printed by the auctioneering firm Hans W. Lange, Berlin, 1937 to 1943.

53 Author’s own calculations of purchases by the 14 commission agents checked by Hans Carl Krüger of Rudolf Lepke’s Auktionshaus, LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 4817, undated (spring (? ) 1936); based on the protocols of five auctions held by Dr. Ernst Mandelbaum and Peter Paul Kronthal in 1935, LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 30, dated 28 August, 14 and 28 September, 9 and 23 October 1935; catalogues (except one) see under Mandelbaum https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/de/sammlungen/artsales.html (251018); publication of licensed commission agents in the catalogues from Rudolf Lepke’s , from catalogue 2103 of 6 June 1936 onwards, Paul Bercovitz missing from catalogue 2105 of 24-26 June 1936 onwards.

54 Author’s own calculations based on the protocol of the auction of the Budge collection in October 1937 in LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 28; auction catalogue Paul Graupe, Die Sammlung Frau Emma Budge Hamburg. Gemälde, Farbstiche, Skulpturen, Statuetten, Kunstgewerbe, Versteigerung am 27., 28. und 29. September [held on 4-6 October] 1937, Berlin 1937, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/graupe1937_09_27 (251018).

55 Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich, 51 (1932), 88; 53 (1934), 111; 59 (1941/42), 184. – See, for example: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6204 ff. Nehring family; no. 5680 ff. Mastai family; brothers diversifying: LABO EA 322768 Otto, Herbert, Hans and Paul Goldstein; LABO EA 65415 Samuel Bercovitz and (no file) Paul Bercovitz; married couples: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 804 Lena Bodenheim; no. 803 Adolf Bodenheim and LAB A Rep. 093-09 no. 590; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 7084 Charlotte Reinheldt; no. 7085 Curt Reinheldt; no. 6295 Elisabeth Nicolai; no. 6294 Carl Nicolai; widows: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2897 Johanna Haasch; no. 2950 Marie Hagemeister; no. 3064 f. Marie Hartmann; no. 4559 Rosina Korb; sister: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 3055 Auguste Hartmann; to be differentiated from spouses who joined the business at a later stage: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5814 Arthur Merkel; no. 5816 Hertha Merkel; no. 345 Eberhard Barg; no. 346 Hildegard Barg; no. 1760 Irmgard Ehrhardt, her husband Franz was given a membership number but no file.

56 Business start-ups during the 1920s: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 421 Dr. Theodor Bauer; no. 885 Theodor Bohlken; no. 2895 Helene Haak; no. 3676 Wilhelm Honeck; no. 5943 Viktor Modrzejewski; no. 8179 Carl Christian Schmidt; no. 9549 Werner Wegner; employees as successors: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 4904 Antonie Küller; no. 73300 Gertrud Stoldt; leaving a firm in order to become self-employed: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 1528 Dr. Viktoria Dingeldey; no. 3064 Gustav Hartmann after Marie Hartmann; no. 5814 Arthur Merkel; no. 6716 Willy Piur.

57 Business start-ups during the 1930s: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 1506 Ella Dieling; no. 2295 Albin Fuchs; no. 2865 Erich Gratkowski; no. 8660 Marie Schulze; no. 9591 Johann Weber; no. 9629 Harry Weinkauf; invalids and disability pensions: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6251 Adolf Neumann; no. 7961 Matthias Schamper; no. 1760 Irmgard Ehrhardt.

58 Count of advertisements in the Berlin directory’s Yellow Pages 1928-1943 for the exhibition “Gute Geschäfte” in 2011, Aktives Museum Faschismus und Widerstand in Berlin e.V., https://www.aktives-museum.de/ausstellungen/gute-geschaefte/ (221018).

59 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6345 Dr. Margrethe Noelle; no. 7305 Walter Röstel; see above-mentioned Graupe, Kaznelson, Krüger.

60 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5738 Günther Mecklenburg; no. 2706 Willem van der Grient.

61 As an example, see the exploitation of the art dealer family Mastai’s stock after they fled as Polish citizens: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5681 Anna Mastai.

62 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 6795 Alfred Popper; no. 2939 Werner van Haersolte.

63 BAB R 9361 V 27842 Wilhelm August Luz; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 7287 Paul Roemer; no. 7631 Fritz (Karl Friedrich) Seiler.

64 LABO EA 57932 Johanna Grünthal, with thanks for the reference to Peter Prölß, Leipzig; LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 311 Rudolf Bahrs; no. 9994 Dr. Waldemar Wruck.

65 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2974 Eleonore Halbscheffel.

66 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 7027 Fritz Rehbein about Axel Kettner-Kronheim, dated 20 March 1937; no. 9994 Dr. Waldemar Wruck, dated 2 May 1937; no. 311 Rudolf Bahrs, dated 7 September 1937; both Robert Ball Nf., owner Johanna Grünthal. – The membership badge had been designed by Richard Klein, published in Mitteilungsblatt der RkbK 2 (1937), no. 6, 16 (1 June).

67 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 3437 Otto von der Heyde.

68 The four dealers are of course well known and have been the subject of extensive research, which is outside the scope of this article: Hildebrand Gurlitt, Karl Buchholz, Ferdinand Möller and Bernhard A. Böhmer. See in this context the later interrogation of the Chamber’s deputy head Erich Mai: National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C., Holocaust Era Assets, Ardelia Hall Collection, Munich Central Collecting Point 1945-1951, Restitution Research Records, Interrogations: Reichskammer Der Bildenden Kunste [sic], CSDIC [Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre] (UK), PW Paper 50. The Reichskammer Der Bildenden Künste [sic], 30 January 1945, fl. 1-54, http://www.fold3.com/image/270045821 ff. (291018).

69 See the chapters in Tiedemann, ed., Die Kammer schreibt, 2016.

70 Anordnung über den Vertrieb minderwertiger Kunsterzeugnisse. Vom 1. Oktober 1940, Schrieber/Metten/Collatz, Recht der Reichskulturkammer, T. 2, X 16, 32 f.

71 Verordnung gegen die Unterstützung der Tarnung jüdischer Gewerbebetriebe. Vom 22.04.1938, RGBl 1938 I 404, http://alex.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/alex?aid=dra&datum=1938&page=582&size=45 (291018); Bruno Blau, Das Ausnahmerecht für die Juden in Deutschland 1933-1945, 3rd edition (Düsseldorf: Verlag Allgemeine Wochenzeitung der Juden in Deutschland, 1965), no. 152.

72 LABO EA 57487 Arthur Abt; LABO EA 70233 Eugen Weissner.

73 See in this context: Christian Fuhrmeister/Susanne Kienlechner, Erhard Göpel im Nationalsozialismus – eine Skizze (January 2018), http://www.zikg.eu/personen/cfuhrmeister/bib-fuhrmeister/pdfs/Fuhrmeister_Kienlechner-Goepel.pdf (010318).

74 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 5741 Otto Meder; see also: LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 2974 Eleonore Halbscheffel; no. 415 Emil Bauer.

75 LAB A Rep. 243-04 no. 8857 (Dr.) Heinz Steinmeyer.