ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

ISSN: 2511-7602

Journal for Art Market Studies

Zoe Cormack

This article explores the links between African artefacts in European museum collections and the slave and ivory trade in Sudan in the nineteenth century. It examines how ‘ethnographic’ collections were acquired from southern Sudan and how this process was entangled with the expansion of predatory commerce. Presenting evidence from contemporary travel accounts, museum archives and from the examination of objects themselves, I argue that the nineteenth-century trade in artefacts from South Sudan was inseparable from a history of enslavement and extraction. This evidence from Sudan illuminates the relationship between collecting artefacts in Africa and other markets. It shows how collecting interests intersected with Ottoman and European imperial networks in Sudan and helps to better understand the history of African collections in European museums.

This article reconsiders practices of collecting in nineteenth-century Sudan and brings new light onto a significant, but under-researched, corpus of African material in European museums. Between 1840 and 1885, up to 15,000 objects from the region that is today South Sudan entered European museums and are now housed in locations as diverse as London, Ljubljana and Perugia.1 Acquired by European traders, explorers, government officials and missionaries, these South Sudanese objects formed early, sometimes the first, major African collections for many museums. They came to be considered ‘ethnographic’ collections, because they reflected objects in daily use and were often claimed to represent the ethnic diversity of southern Sudan.

The nineteenth century was a foundational period for ethnographic museums and collections in Europe: a result of the interconnected growth of imperialism and the scientific study of culture. Another significant backdrop for the movement of artefacts from southern Sudan was the Ottoman-Egyptian invasion of Sudan and the region’s incorporation into global economic networks through the trade in ivory and enslaved people. The creation of these collections was entangled with this expansion of the state and commerce.

As has been argued elsewhere in colonial Africa, collecting was always mediated by other political and economic relations.2 In southern Sudan, there is considerable evidence that the slave and ivory trade determined the access and relationships that made assembling ethnographic collections possible. This dependence was sometimes uneasy and collecting was also propelled by geographical exploration of the River Nile, missionary activity and a range of other proto-Imperial interests. Nevertheless, southern Sudanese collections provide a striking example of how the expansion of trade and imperial control was fundamental to the formation of museum collections. This article examines this relationship – looking at both the actions of traders and collectors and southern Sudanese responses and innovations. Then, to show how predatory commerce shaped one particular museum collection, it takes a detailed look at a collection assembled in 1859-61 by the Italian explorer, Giovanni Miani, while he attempted to discover the source of the Nile, which is now on display in the Museum of Natural History in Venice.

An important part of this story starts in 1820, when Muhammad Ali Pasha, the Ottoman ruler of Egypt invaded Sudan, motivated by a desire to obtain both natural resources and slave soldiers to bolster the Egyptian army.3 Ottoman-Egyptian rule lasted until 1885 when the Mahdist rebellion overthrew the government at the siege of Khartoum. Khartoum itself was founded in 1825 and soon became a thriving commercial centre. Between 1839 and 1841, the Egyptian government sponsored a series of naval expeditions that succeeded in breaking through the southern swamps of the upper Nile and reached the island of Gondokoro, near to present day Juba (the capital city of South Sudan). Southern Sudan was thus “opened” to commerce, as well as to missionaries, traders and explorers, hoping to make geographic discoveries about the source of the Nile and Central Africa.

Trade was initially a government monopoly focused on ivory, but it soon extended to private trading companies and a form of commerce emerged which was built on raiding and disruption.4 At first, the focus of trade was ivory, but by the late 1850s it increasingly centred on enslaved people (supplying a growing market in the Nile Valley and sustaining the system of trade itself, which had become dependent on enslaved labour).5 Trading companies established a network of stations called zariba (Arabic pl. zara’ib). These were garrisons of varying size, connecting waterways with territory further inland, for the export of raw materials. Zara’ib had an extractive relationship with surrounding communities – frequently raiding and exacerbating local conflicts to extract both human and material resources. By the 1860s, the trade network extended as far as north-eastern Congo and into southern Darfur. Some trading companies became very powerful, presiding over virtual mini-states. Concerned by these developments, the Ottoman-Egyptian government sought to regain its control of southern Sudan. New government posts were established and several European administrators were brought in, supposedly to curtail the slave trade.6 The example of southern Sudan highlights the wide spectrum of colonial collecting – exploring practices of collecting at the intersection of Ottoman and European imperialisms. These activities have resulted in the presence of South Sudanese objects today in countries, such as Italy, without a “direct” colonial relationship. This history underscores the expansive networks involved in the dispersal of African art and material culture into European museums in the nineteenth century.

During Ottoman-Egyptian rule in Sudan, there was a growing market for “White Nile curiosities”, a term that was used to describe material culture originating from southern Sudan and central Africa.7 Henri Delaporte, the French consul in Cairo from 1848-1854, acquired a collection (now in the Musèe du Quai Branly in Paris) of “weapons, clothing, ornaments, fetishes, musical instruments, utensils of various kinds” from “the Negro peoples who are scattered on both banks of the White Nile” through his “relations with Arab merchants trading in Sudan”.8 By the 1870s, there was a shop in the Khartoum souk where an array of “African” artefacts could be purchased.9 The price of central African “curios” in Cairo had been driven up by rising numbers of travellers to the region.10

The growth of this market was a direct result of the expanding trade networks in southern Sudan. A comment made by the traveller and collector Wilhelm Junker leaves no ambiguity about the condition of supply and demand

The Khartum [sic] merchants having found out that travellers hunted for articles in use by the negroes and would pay a good round sum for a rare and perfect specimen, the zeriba soldier stole anything he could lay his hands on from the negroes and disposed of it as a “curiosity” to the jallaba [traders] about to return to Khartum.11

When it came to collecting in southern Sudan, Europeans were equally dependent on the trading companies. The violence associated with the zariba trade and the expansion of state authority also created opportunities to obtain objects. These dynamics are evident in the earliest recorded collection made in southern Sudan to enter a museum. It was assembled by a German traveller, Ferdinand Werne, who accompanied the Egyptian voyages down the Nile to Gondokoro in 1840. He donated 126 objects from this trip to the Royal Museum in Berlin in 1844. His account shows how collecting was, from the outset, entangled with expedition’s the use of force and embedded within new forms of bargaining and extraction between local people and outsiders. Werne witnessed the crew taking objects from riverside villages as “curios”.12 In a revealing passage, he described how a year earlier, a trader named Thibault had stolen artefacts from a village following a violent altercation and murder of the “shiekh”:

The inhabitants of this village were harshly used by the former expedition. At that time they brought four oxen as a present, and gave a sheep to Thibault, who, because it was somewhat swollen, took it to be poisoned. This circumstance was sufficient cause to incite the crew to go ashore, to surround the village on all sides, and to shoot down, in a shameful manner, the Shiekh, and several others who had fled with him into the neighbouring marshes. Thibaut made a very pretty booty here, consisting, amongst other things, of a square quiver, somewhat curved at the top, altogether of antique form; besides large felt caps similar to the ancient Egyptian caps of the priests, high and obtuse in the front; broad collars for bulls, set round with iron spindle-shaped ornaments, which were hung up in the great tukul [cattle byre].13

Another important example of the close relationship between violent trade and collectors is the “throne” and two spears of Kwathker Akot, the Divine King of the Shilluk people, which are now housed in the Archaeological Museum in Perugia, Italy.14 These objects were purchased by Orazio Antinori (a Perugian traveller and a founder of the Italian Geographical Society) from the trader Mohamed Kheir in Kaka town in 1861. The background to this purchase was conflict over control of the Nile trade. Kwathker had expelled the traders from the Shilluk Kingdom in 1860. Subsequently, Mohamed Kheir (who had been given permission by the government to trade in Shilluk territory) retaliated with several attacks against the Kingdom.15 The objects were taken by Kheir as a trophy following a battle in 1861, in which Kwathker was defeated and forced into hiding in the southern part of the Shilluk Kingdom.16 One of the spears (inventory number 49481) is pierced by a bullet hole.

Studies of colonial collecting have also emphasised how African and indigenous agency have shaped museum collections, even in contexts of violence.17 The cultures of trade created opportunities and made space for innovation within an overall picture of exploitation. Werne’s early account describes how he obtained objects in a Bari-speaking area in exchange for Venetian glass beads, emphasising that local people were keen to obtain these beads and willingly parted with their material culture.18 What “free will” meant in the context of such coercion is highly debatable, but there is evidence that some of the exchanges took place on more negotiated terms. Notably, the Bari king Logunu of Bilinyan boarded Werne’s boat and met the ship’s captain (Salim Qapedan), who gave him a large bronze cow-bell; Logunu reciprocated this gift with an iron stool and a small wooden statue representing a woman. Ten years later, an Italian missionary who visited Bilinyan found the cow-bell had been repurposed as a receptacle to wash rain stones, objects that were central to Bari religious and political life.19 This is a revealing indication that the practice of exchanging objects could be drawn into existing cultural systems and relationships of power.

The exchange of objects at zara’ib and government stations was part of the way relationships were brokered between local people and incomers. As the century progressed, these practices took on increasingly complex forms. For example, one prominent Zande “dragoman” (an Ottoman word for intermediary) known as “Ringio” established his own collection of “ethnographic” objects, which he sometimes displayed or gifted to incoming Europeans, as part of a performance of authority and alliance.20 While these exchanges nevertheless took place in a backdrop of extreme violence, it has also been argued that (in more peaceful areas and periods) zariba were spaces of artistic innovation, because of the new encounters they facilitated, both between South Sudanese and foreign cultures.21 Enrico Castelli has suggested that many small figurative statues attributed to Bari people (well represented in European museum collections) were manufactured by Bari craftspeople expressly for the trade in ethnographic objects, because Europeans where particularly keen to acquire this figurative work.22

Giovanni Miani’s collection offers a striking insight into the links between collecting and predatory commerce. Assembled at the height of commercial extraction in southern Sudan, it consists of approximately 2000 objects obtained on an expedition between 5 December 1859 and 22 May 1860 to discover the source of the Nile (as well as during a period in Khartoum in 1861). The expedition was facilitated by the company of Andrea de Bono (d.1871), a Maltese trader who operated south of Gondokoro.23 Most of Miani’s movements were with his trading company.

Miani’s career was unusual. He was born in the small town of Rovigo in the Veneto in 1810. He trained in music in Venice. After fighting for Garibaldi in the Italian wars of the Risorgimento, he lived in Egypt where he learnt Arabic and became interested in exploration. With the support of the Egyptian government and French Geographical Society he travelled through southern Sudan looking for the source of the Nile in 1859-60.24 He then returned to Venice, with a collection of objects and spent several years involved in geographical debates in Europe. He returned to Sudan in 1870 to take up the role of director of the zoological gardens in Khartoum. He died exploring Mangbetu territories in north eastern Congo in 1872, from which undertaking a smaller collection (which included human remains as well as material culture) was donated to the Italian Geographical Society and later transferred to the Pigorini Museum, Rome (now Museo della Civiltà).25

Miani’s first and largest collection was donated to the city of Venice and first put on show at the Casa dell’Industria in 1862. It was transferred to the Correr Museum in 1866 and then in 1880 to the Palazzo Fontego dei Turchi, which later became the Natural History Museum Giancarlo Ligabue - Venice. In 1940, a selection of objects was sent to Naples for the Mostra triennale delle Terre Italiane d’ Oltremare – a fascist-colonial exhibition celebrating Italian imperial achievements. These were lost in Allied bombing shortly after the exhibition opened.26 However, most of the collection survives and is today on display at the Natural History Museum Giancarlo Ligabue, in a style reflecting the original nineteenth-century arrangement.27

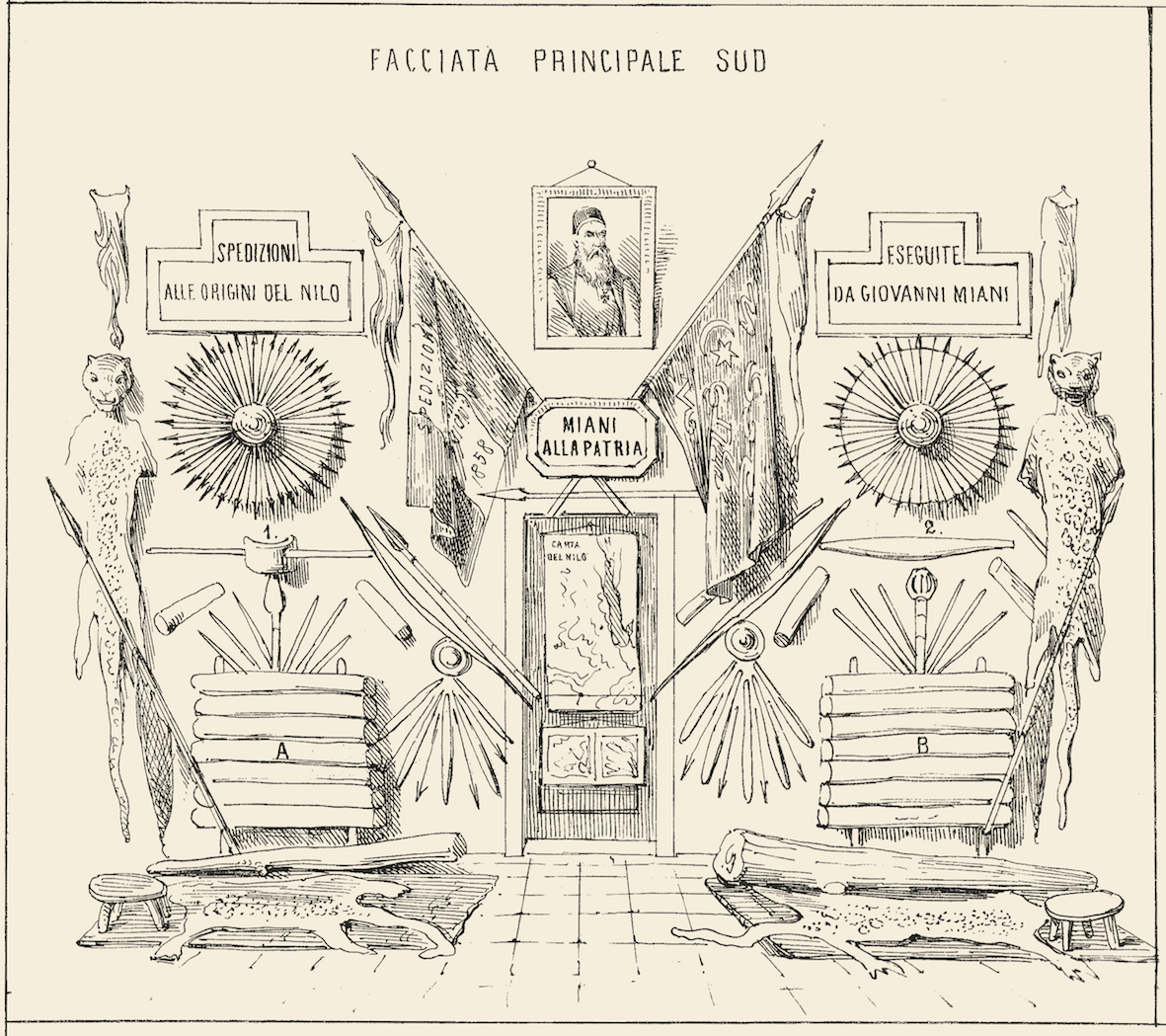

It can be difficult to establish exactly how African objects now housed in museums were obtained in the mid nineteenth century, as this information was often not recorded. However, in this case, there is primary documentation that allows us to build up a reasonable picture of Miani’s collecting practice. He left an account of the first journey in southern Sudan, Spedizioni alle Origini del Nilo, published in 1865 and an edited version of his diary and letters, Diari e Carteggi di Giovanni Miani (1858-1872) (which also includes details of his 1871-1872 trip to Mangbetu) was published in Milan in 1973. Spedizioni includes a description of the collection (pp.97-105) and a corresponding lithograph (produced in 1865) showing its original arrangement is conserved in the archive of the Civic museum of Venice. (See Fig 1)

It has been suggested by Enrico Castelli, the anthropologist who re-catalogued the Miani collection, that this lithograph may be the earliest record of a self-consciously “ethnographic” display in Europe.28 Miani arranged his collection by ethnic group, and distinguished it from other contemporary collections from southern Sudan for this reason. His preface to the collection states:

In the museum in Paris, you can see various objects from the White Nile, which the consul Delaporte brought from traders in Cairo. In the museum in London, there are also many objects from the aforementioned river, sent by several travellers. But in neither of these museums can you see objects classified by tribe, as we see in this collection.29

Fig: 1. Detail of a lithograph showing the original arrangement of Giovanni Miani’s collection (1865). Library of the Museo di Storia Naturale Giancarlo Ligabue in Venice (Miani 10/6, c. 5r). Image courtesy of the Museo di Storia Naturale Giancarlo Ligabue, Venice.

The central part of the exhibition was a display relating to the expedition as a whole. It included ethnographic artefacts, alongside flags from the expedition, maps and a portrait of Miani himself. The objects were then divided into discrete displays (which Miani called “trophie” - trofei). First on the left was the ‘Auidi’ (Madi) display, followed by two “Barri” (Bari) displays, a “Scir” and “Bor” (Dinka) display, two Azande displays - one of the “Niam Niam Makaraka” (Adio Zande from the Yei River area) and another from the “Niam Niam Bahr el Ghazal” (central Zande) and a small “Nauer I Sceluki” (Nuer and Shilluk) display. Although it made gestures towards showing the material culture of different ethnic groups, a primary concern of the display was to celebrate Miani’s exploration of the Upper Nile.

Looking closely at Miani’s writing, it is evident that he was heavily dependent on trading companies to travel in the South. He travelled with one of the most notorious, de Bono’s company. It was widely reported at the time that this company were heavily involved in the slave trade. Samuel Baker wrote, ‘de Bono’s people are the worst of the lot, having utterly destroyed the country’.30

The origins of the objects in the Madi display (obtained in the region south of Juba) dramatically show how acquiring objects was facilitated by Miani’s close relationship with the trading company. Miani gives a detailed description of how he obtained objects in the context of a massacre perpetrated in a Madi village. He first describes the attire of the “king” of the Madi

He had an iron crown in his head like the ancient Spartans, an ebony disk surrounded by copper, decorated from top to bottom with 18 [cowries]. The belt was also laced with [cowries] that, among the Africans, are used for coins, and various old green venetian beads. He had a fabulous fabric wrap, a snake skin covered bow. The warriors around him had iron-clad implements. They carried large oval shields made from elephant skin. Their spears were longer than our bayonets. Only the king was wearing sandals on his feet. All these spoils are seen in my collection.31

Miani explains how they returned to the village to obtain ivory, which the traders planned to acquire in exchange for a woman who had been captured (they intended to offer her to the “king” as a wife). They also requested to be given a bag of grain. The Madi “king” refused to give the soldiers grain and ordered them to leave the village. At this point, a fight broke out. The soldiers brutally killed the “king”: his hands were cut off to remove his bracelets, his body (dismembered and castrated) was staked to the soldier’s weapons and paraded as a sign of victory. Many inhabitants of the village fled and others were burned alive when the village was set on fire (on Miani’s orders).

It is striking that, according to his own account, Miani was not simply an observer, but an instigator of extreme violence. Indeed, some instances of violence were a direct outcome of the collecting process. He writes, for example, that the soldiers took “many musical instruments [and clothes from the women of the village], for they knew that I wanted to make a collection.”32 He later states, “it was only possible to obtain these objects after the war with the Madi, in which the king was killed.”33 He did not try to disguise the source of these objects, but celebrated their violent process of acquisition: the focal part of his arrangement of his collection included two leopard skins and two head rests taken from the Madi raid.34

Fig: 2. The ‘Madi Case’ in the Giovani Miani gallery (2018). Image courtesy of the Museo di Storia Naturale Giancarlo Ligabue, Venice.

For most material in the Miani collection, we cannot recover this level of detail about the interplay between trade, collecting and violence. In the town of Kaka on the White Nile, Miani simply records that he was “able to gather some of the costumes and some idea of the Shilluk language.”35 Likewise, on an expedition to the Adio Zande territory on the Yei River, he describes some of the material culture he saw: “ivory war trumpets and very original straw hats”, then simply notes that these objects are now “seen in my collection”.36 However, there are strong hints as to what the context of this collecting might have been. We know that Kaka was at the time a significant centre in the fight for control of the Nile trade between traders and the Shilluk kingdom. The example of Mohamed Kheir and Kwathker Akot’s throne and spears discussed above shows that valuable objects were being acquired because of these shifting political dynamics. Likewise, at the time he acquired the Adio Zande objects he was again accompanied by de Bono’s private army, who were using enslaved labour to collect ivory.37 Even if unstated, the acquisition of the trumpets and straw hats was backed up by the real threat of force.

Yet, while we can trace a symbiosis between trade and collecting there was a considerable amount of tension in this relationship. Traders and those who made collections viewed each other with suspicion. Many collectors were quick to denounce the depredations of the slave and ivory trade, while continuing their dependence on exploitative practices. From a collecting point of view, the potential consequences of these tensions are especially clear in Miani’s account of his final expedition to Mangbetu in 1872, in which he travelled through the stations of the Coptic trader Ghattas. In his diary and letters from this journey he makes constant reference to his mistreatment by Ghattas’ agents.38 Days before his death he was forced to abandon a large part of his collection at a zariba because the agent would not give him sufficient porterage.39

Occasionally – albeit tentatively – it is possible to read Miani’s account against its grain, to gather a sense of how southern Sudanese felt about his presence. In a telling encounter at Makedo (a cataract on the White Nile, just north of the Madi village), a Bari chief approached Miani and the trading company soldiers. Miani asked his permission to pass and offered the chief copper bracelets, a trumpet and a ring in return for their passage. Although the chief acquiesced to their presence, he told Miani: “You are here, like the python”.40 Whether Miani realised it (or more likely not), the python is a symbol of evil in Bari cosmology. What he recorded, probably unwittingly, is a coded but clearly hostile reaction to his presence. It is possible that further research, if it could tap into oral history of this expedition in South Sudan, might yield further insight into these dynamics.

Miani’s collection and its documentation provides an opportunity to see the intimate relationship between commerce and collecting in nineteenth century Sudan. The precise dynamics underpinning different collections varied. Henri Delaporte’s collection (now in the Quai Branly in Paris) was purchased in Cairo, through relationships with traders operating in Sudan; Delaporte never visited southern Sudan personally. Yet, individuals who did travel to southern Sudan in this period were dependent on commercial networks for movement and access; Miani provides a detailed insight into what the realities of this relationship could be.

The historical relationship between trade and collecting in Sudan (and Africa more widely) is multifaceted. In some respects, this relationship was straightforward, as Miani’s case demonstrates; trade networks facilitated the presence of collectors in southern Sudan and determined their access. As Wilhelm Junker described, traders often stole objects from people they encountered and sold them to collectors. In other respects, these relationships were more complex: as commerce reconfigured the social geography of southern Sudan. As Sidney Kasfir noted, the zariba trading stations brought different communities into contact with one another and created new opportunities for exchange. Trade created a new class of intermediaries – men like Ringio who assembled his own collection - who were able to negotiate between indigenous communities and incomers, further facilitating the movement of objects. Trade also created the conditions for local material culture to be commodified and even changed patterns of production in response to a market. It is likely, as Castelli argues, that a number of southern Sudanese objects in museums were made directly for the European market.

An important factor underlying the creation of these collections was violence. Indeed, the Sudanese case starkly illustrates this broader characteristic of colonial collecting in Africa. The objects under study were removed in the context of violence and collusion, which involved the use of force in pervasive, but sometimes diffuse and complex patterns. The collectors (as in Miani’s case) sometimes actively participated in the violence, and some of the objects were quite literally the trophies of war. Even in instances when objects were acquired on more negotiated terms, the collections were assembled amidst the threat of force. These relationships between trade, collecting, colonisation and violence are embedded in these South Sudanese collections, even though this is often obscured in their display.

This research was undertaken during a Rome Fellowship at the British School at Rome (2016-2017). I am grateful to the Museo di Storia Naturale Giancarlo Ligabue in Venice (especially Silvia Zampieri) for their support of my research on Giovanni Miani’s collection and the Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria in Perugia for the opportunity to consult the Orazio Antinori collection. My thanks to Stefania Perterlini, Permissions Officer at the British School at Rome, for her help accessing collections in Italy.

Zoe Cormack is the Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow at the African Studies Centre, Oxford University.

1 Zoe Cormack, South Sudanese Art and Material Culture in European and Russian Museums: A Working Inventory, 2019, https://southsudanmuseumnetwork.files.wordpress.com/2019/01/southsudanobjectsv3.pdf.

2 Johannes Fabian, Curios and Curiosity: Notes on Reading Torday and Frobenius, in Enid Schildkrout and Curtis Keim, eds., The Scramble for Art in Central Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

3 P.M Holt and M.W Daly, A History of The Sudan: From the Coming of Islam to the Present Day (Harlow: Pearson, 2011), 35–36.

4 Justin Willis, Violence, Authority, and the State in the Nuba Mountains of Condominium Sudan, in The Historical Journal 46, no. 1 (2003), 102.

5 Richard Gray, A History of The Southern Sudan 1839-1889 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 60–61.

6 Holt and Daly, A History. 55–56.

7 George Melly, Khartoum and the Blue and White Niles, vol. 2 (London: Colburn and Co., 1851), 117.

8 Enrico Castelli, Origine Des Collections Ethnographiques Soudanaises Dans Les Musées Francais (1880-1878), in Journal Des Africanistes 54, no. 1 (1984), 99.

9 Camillo Sapelli di Capriglio, Nel Sudan Orientale (Milan: Fratelli Bocca, 1942), 89. Robert Joost Willink, The Fateful Journey: The Expedition of Alexine Tinne and Theodor von Heuglin in the Sudan (1863-1964) (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011), 306–8.

10 Angelo Castelbolognesi, Viaggio Al Fiume Delle Gazzelle (Nilo Bianco), 1856-1857 (Ferrara: Liberty House, 1988), 26. Ezio Bassani, 19th-Century Airport Art, in African Arts 12, no. 2 (1979), 35.

11 Wilhelm Junker, Travels in Africa in the Years 1875-1878, trans. A.H Keane, vol. 1 (London: Chapman and Hall, 1890), 429.

12 Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, Sources, with Particular Reference to the Southern Sudan, in Cahiers d’Etudes Africaines 11, no. 41 (1971), 135.

13 Ferdinand Werne, Expedition to Discover the Sources of the White Nile in the Years 1840, 1841, trans. Charles William O’Reilly, vol. 1 (London: Richard Bentley, 1849), 176.

14 The inventory numbers at the Museo Archeologico Nazionale dell’Umbria for these items: “Throne” (large wooden chair), 49674; Elephant spear, 49481. A second spear attributed to Kwathker was catalogued but now appears to be lost.

15 Enrico Castelli, ed., Orazio Antinori in Africa Centrale 1859-1861. Materiali E Documenti Inediti (Perugia: Ministero Beni Culturali e Ambientali, 1984), 63.

16 The objects were likely taken by Khier at a battle in Fashoda (Kodok) – in Febuary or May, or in Kaka town itself in April 1861, see John Udal, The Nile in Darkness: Conquest and Exploration, 1504-1862 (Norwich: Michael Russell, 1998), 476.

17 Enid Schildkrout and Curtis Keim, Objects and Agendas: Re-Collecting the Congo, in The Scramble for Art in Central Africa, 5–6; Zachary Kingdon, Ethnographic Collecting and African Agency in Early Colonial West Africa A Study of Trans-Imperial Cultural Flows (London: Bloomsbury, 2019).

18 Werne, Expedition. 341.

19 Simon Simonse, Kings of Disaster: Dualism, Centrism and the Scapegoat King in Southeastern Sudan (Kampala: Fountain Publishers, 2017), 100–101.

20 Junker, Travels, 305–6.

21 Sidney L. Kasfir, Ivory from Zariba Country to the Land of Zinj, in Doran H Ross, ed., Elephant: The Animal and Its Ivory in African Culture (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum of Cultural History, UCLA, 1992), 309–27.

22 Enrico Castelli, Bari Statuary: The Influence Exerted by European Traders on the Traditional Production of Figured Objects, in RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 14 (1987), 86–106.

23 For an apologetic account see Charles Catania, Andrea de Bono: Maltese Explorer on the White Nile (Leicestershire: Upfront Publishing, 2002).

24 Maria Teresa Pasqualini Canato, La Vita di Giovanni Giacomo Miani, in Gianpaolo Romanato , ed., Giovanni Miani E Il Contributo Veneto Alla Conoscenza dell’Africa. Esploratori, Missionari, Imprenditori, Scienziati, Avventurieri, Giornalisti (Rovigo: Minelliana, 2003).

25 Oggetti Di Monbuttu: Raccolta Da Giovanni Miani E Pervenuti in Dono Alla Società Geografica, in Bollettino Della Società Geografica Italiana, July 1875, 232–33.

26 For a full list of lost objects, see the library of the Natural History Museum, Venice, Fondo Miani, 10/2 cc.15r-26r.

27 Enrico Ratti and Margherita Fusco, Viaggio Verso Le Sorgenti Del Nilo: La Collezione Etnografica Giovanni Miani, in Memoria Del Museo Civico Di Storia Naturale Di Verona - 2 Serie. Monografie Naturalistiche 4, 2009, 193–94. Some objects in the collection were transferred and are now housed in Museo della Civiltà, Rome and the Weltmuseum, Vienna.

28 Enrico Castelli, Le Collezioni Etnografiche Di Giovanni Miani a Venezia, Roma E Vienna, in Gianpaolo Romanato, ed., Giovanni Miani E Il Contributo Veneto Alla Conoscenza dell’Africa: Esploratori, Missionari, Imprenditori, Scienziati, Avventurieri, Giornalisti (Rovigo: Minelliana, 2003), 177.

29 Giovanni Miani, Le Spedizioni Alle Origini Del Nile (Venice: Co’Tipi di Gaetano Longo Impr., 1865), 97.

30 Gray, A History, 83.

31 Miani, Spedizioni, 48 and Giovanni Miani, Diari E Carteggi Di Giovanni Miani (1958-1872), ed. G. Rossi-Osmida (Milan: Longanesi, 1973), 248-251. Inventory numbers for objects described in this passage that can be identified with certainty: “ebony disc...decorated with cowries” SNMI0156; “belt... with cowries [and] green venetian beads” SNMI0139; “sandals” SNMI0224.

32 Miani, Spedizioni, 53.

33 Miani, Spedizioni, 98.

34 Miani, Spedizioni, 97.

35 Miani, Diari, 167.

36 Miani, Spedizioni, 36.

37 Miani, Spedizioni, 37.

38 Miani, Diari, 419.

39 Miani, Diari, 382.

40 Miani, Diari, 212–13.